Cursory impression: Minneapolitans do not like police, or rather, they don’t like Minneapolis police.

I am not talking about the people one might expect to show antipathy toward cops on the day former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin goes on trial for the murder of George Floyd: The activists (or whoever) spray-painted ACAB (“All Cops Are Bastards”) on an overpass near the Target store that was looted two days after Floyd’s death. I am not talking about the girl who offered us cake at the “Land Back Now!” cookout near the Basilica of Saint Mary, or the security guy who, after he tells us about his eight kids, including triplets, the boys identical and the girl fraternal (“The OBGYN said, ‘Boy, you got some crazy sperm if you can do that in 24 hours'”), says George Floyd Square, which he sometimes patrols, “is about peace.”

I am talking about middle-of-the-road locals, the white journalist who says to her 30-year-old son, “The Minneapolis police have been terrible since before you were born.” The son who calls the former head of the police union, Bob Kroll, “the Antichrist.” The full-blooded Native American who tells me, “The last time a cop here pulled a gun on me, it was for walking down the street with my hands in my pockets.”

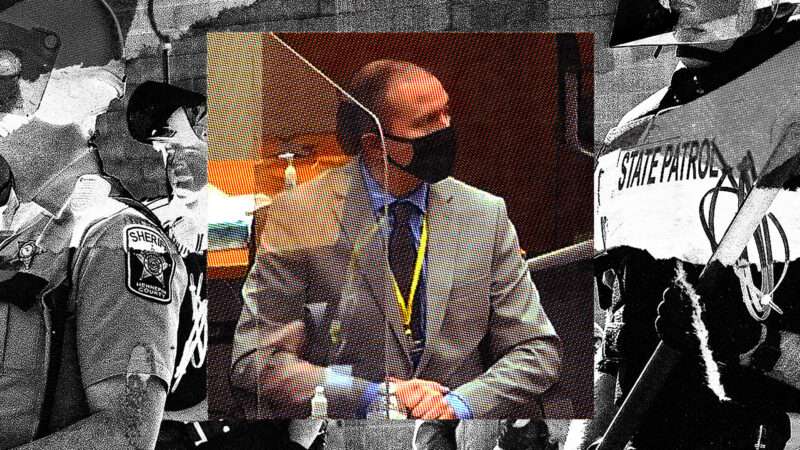

Since the death of George Floyd, I’ve had in my mind two images of Minneapolis: as a city under siege and as a place moving, if somewhat jerkily, toward necessary healing. It’s hard to argue that Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds (upped yesterday, from 8:46, in opening statements by the prosecution) is not a tactic the Minneapolis Police Department (or any police department) should rethink or do away with. That those minutes have exploded into the consciousness on a worldwide level is undeniable. This morning, I have two people—one in Portland, Oregon, the other in London—arguing on my Instagram about Floyd’s death and proportionality and how “one might wonder if there is a bit more going on here.”

As someone who covered the protests in Portland during the summer and fall of 2020, I know about proportionality, know there is more going on here, know that no amount of fire setting and window breaking, of tear gassing or neck kneeling, will satisfy those who seek healing through destruction. We’ve taken sides; don’t, as my late father used to say, “confuse me with the facts.”

I came to Minneapolis yesterday naïve about the situation on the ground, but for one aspect: The city, just after Floyd’s death, had touched off days of massive street violence, hundreds of buildings torched, and a five-mile stretch of Lake Street sustaining heavy property damage. I knew that law enforcement had been overwhelmed. And I wondered, with the Chauvin trial underway, if there was a sense of dread that, should the outcome be unsatisfying, the city would burn again. Were Minneapolitans afraid? Resigned? Hopeful? What had they done in the wake of Floyd’s death and what were they doing and feeling today? I’m asking people of different stripes, people who might usually not be interested in varying perspectives, might have recently or long ago decided that Person X is the enemy. I offer the perspectives anyway. Call me Pollyanna.

First up: two active duty Minneapolis-area officers, who spoke to me separately and on the condition of anonymity (and identified here as J and N), the night before the trial began, about their deployment immediately after Floyd’s death and what happens now. Comments have been edited for length and clarity.

J: “Almost as soon as we arrived at our staging area, we were ordered to put on our riot gear—which we had never worn—and deployed to defend the Fifth Precinct. This was [May 28], one day after the Third Precinct burned to the ground. We marched in from about five blocks through crowds screaming, throwing bottles, launching fireworks at us from both sides of the street…Later in the evening, a woman almost ran us over in her vehicle while we stood on a riot line.

“The radio traffic sounded like a fucking zombie movie, with the Minneapolis Police Department officers screaming they were facing massive crowds and could not hold their positions without relief. The cops looked absolutely wrecked. Every squad car had a broken window and many were held together with duct tape. I had to tell family to hunker down and not bother calling 911, because nobody was coming; one of the guys I know at MPD sent me a text telling me there was nobody left to answer calls.”

N: “Everybody had to go in and it was an absolute shit show because nobody knew what to do or where to go. We had never dealt with anything like that. I don’t think the city has seen anything like this ever…Almost immediately there were rental cars everywhere, with the plates taken off of them, people driving a hundred miles an hour up and down streets, it was the Wild West, I mean, it was lawless and then some.”

J: “There was a huge commercial building threatening an adjacent public housing complex that was occupied. Normally, if you have a large fire like that, law enforcement is going to evacuate the adjacent buildings. That area of Lake Street is largely controlled at this point by rioters. So we need to move these people out of there to get the fire department in there. Law enforcement, they’re using a lot of that stuff; just an ungodly amount of ordnance that gets dropped there: less-lethal rounds, tear gas, impact munitions.

“One of the things that’s very frustrating to me about this whole thing is: Now Portland can’t use tear gas. Now Seattle can’t use tear gas. It’s like, if you want to take that away from us, you’re leaving us with sticks and bats. The only reason those officers didn’t have to basically engage in medieval hand-to-hand combat with these people is because of the overwhelming superiority of less lethal munitions we have there.

“So the crowd gets pushed back. Then we actually get approached by two of the [black bloc] ‘medics.’ And they’re like, ‘You guys need to go help the people in that [burning] building, people that need help.’ It’s like, okay well, maybe stop setting buildings on fire then?

“If you watch Portlandia, the jokes also make sense in Minneapolis. It’s a very similar city, culturally; Minneapolis has a huge contingent of the anarcho-socialist, crust-punk, antifa-type milieu, in the same way Portland does. My impression of the people that were engaging law enforcement in the area where we were was, they’re all wearing black; some of them have their little anarchist banners or whatever. And they were equipped in a way that made me think, we were dealing with kind of the white anarchist crowd, because those folks know what to bring. They have their bike helmets and their kneepads and elbow pads and they’re covering their face in a more intelligent way to deal with tear gas than the average protestor, because they’d read all those CrimethInc. manuals and stuff.”

N: “The narrative that was pushed out to the media was, ‘The only people who caused destruction were from out of town, it was all out of state.’ Well, that’s fucking bullshit. I saw plenty of local assholes mixed into this. These riots were happening in every city and it wasn’t like, everyone’s just switching teams for the night.”

J: “The next day [May 29], 300 troops were deployed to the state Capitol to, to defend it from no one. There were National Guard and armored vehicles on a completely empty lawn, protecting the governor’s office from an empty square. The media showed up, took pictures, and left; the governor issued a tough-sounding press release. Meanwhile, they could see the smoke columns rising over Minneapolis in the distance. It was a complete failure of leadership and massive misuse of resources.”

N: [With the Chauvin trial underway], “there’s intelligence coming out that folks from Portland, Seattle, New York, Austin, and other activist cities are traveling to Minneapolis to be there for this. You’re not only dealing with the hometown contingent. You’ve got a lot of out-of-town people. I mean, those folks are not going to miss the trial.”

J: “There’s probably a solid core of at least 300 [local activists] that you can reliably count on. That’s me just guessing based on what I’ve seen in the past…The issue is, we have rules we have to follow—as we should—and they don’t. They’re drawing on years and years of theory of how to effectively engage government forces in a psychological warfare campaign. All these people, they’ve read Mao, they’ve read [activist] Saul Alinsky. Their purpose is to provoke the appearance of a disproportionate response from law enforcement, to bring more people to their cause and gain a greater critical mass on the street. That’s going to be a real question with this upcoming stuff: How much do we hold back versus, just snuff it out right away and make the arrests we need to make and remove the accelerants from the equation?”

N: “You have to arrest the main instigators. You just have to arrest people, period. And we didn’t do that [last time]. There was no infrastructure in place for it. It’s still a logistical nightmare for mass arrest.

“The National Guard has already been activated, so they’re going to help in a preemptive way, versus responding two days later away. We’ll already have them; we’re much more prepared. We’re not caught with our pants down, like last time.

“Our higher-ups are saying, ‘We’re preparing for the worst.’ [The day the trial starts], we go into not ’emergency level,’ but a more heightened state, through the length of the trial. I think [what happens to the city] totally depends on the verdict. I think if Chauvin’s acquitted, we’re fucked. There’s no other way to put it.”

J: “There’s folks out there that are going to take any excuse to engage in civil unrest with us. [The jury] going for the manslaughter and not the murder, I think, will be good enough for them [to riot].”

N: “The jury is from Hennepin County. I can’t imagine, in the back of their minds, they’re not thinking, ‘Boy, I can’t say not guilty, regardless of the circumstances, because I don’t want my city to burn.’ I feel like that’s going to play into it. I’m just speculating, but I feel sorry for those folks. I really do. I would not want to be in that position.

“I’d like to think that we’re more prepared, but I just don’t know if this [trial] is going to be a magnet for crazies from all over the U.S. to come here and wreak havoc. My guess is there will be fewer just regular folks who are just out protesting because they’re upset, and there’ll be less of those people to hide amongst. I don’t know. Maybe I’m just being hopeful.”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3fwIHF9

via IFTTT