Gov. Jay Inslee released the following statement [Thursday] announcing his support for legislation currently being written that would outlaw attempts by candidates and elected officials to spread lies about free and fair elections when it has the likelihood to stoke violence.

“January 6 is a reminder not only of the insurrection that happened one year ago, but that there is an ongoing coup attempt by candidates and elected officials to overturn our democracy. They are willing to do this by provoking violence, and today I proposed we do something about that in Washington.

“Soon, legislation will be introduced in the state House and Senate that would make it a gross misdemeanor for candidates and elected officials to knowingly lie about elections. The proposed law is narrowly tailored to capture only those false statements that are made for the purpose of undermining the election process or results and is further limited to lies that are likely to incite or cause lawlessness,” Inslee said.

The U.S. Supreme Court has made it clear that speech can be limited where it is likely to incite lawlessness, Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969). Unlike the state supreme court decision in Rickert v. State, Public Disclosure Com’n, 161 Wash.2d 843 (2007), which addresses false statements made by one candidate about another candidate, this legislation is not about what candidates can say about each other.

“This legislation attempts to follow the relevant U.S. and state supreme court opinions on this issue. We’re talking about candidates and elected officers knowingly throwing bombs at democracy itself when doing so is likely to result in violence,” Inslee said. “We can outlaw actions that provoke political violence and in doing so also protect our democracy. There is more that can be done by states and Congress to protect our democracy. I am open to any proposal that will protect the will of the voters and the institutions they use to decide who governs them.”

There’s apparently no draft statutory language yet, and it’s possible that the law would be so limited as to be both constitutional and likely redundant of existing law: If it’s limited to speech that (1) had the purpose of persuading people to commit crimes (and not just “the purpose of undermining the election process or results”), was (2) likely to have that result, and (3) the result was intended to and likely to be imminent, which likely means within hours or days (an element missing from Inslee’s description ), it would indeed fit within the Brandenburg v. Ohio “incitement” exception.

Shouting “burn it down” or “break in and ransack” to a mob standing in front of a building, with the purpose of causing them to commit crimes, is constitutionally unprotected—indeed, whether the speech consists of knowing lies or even opinions or truthful statements. (R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul might preclude incitement laws that are selectively targeted towards statements about elections, but that’s a complex question.) Yet such speech is already likely illegal under Washington’s general criminal law (see also this case interpreting that statute).

But I assume, based on the Governor’s general statement, that he has bigger fish to fry: I take it that he’s after knowing lies that risk long-term harms (whether attempted revolution or criminal noncompliance with the law) and not just imminent ones. This is a factually perfectly plausible concern. Indeed, it is an old concern, which dates back at least to the Founding era, and in particular to the debates about the Sedition Act of 1798 and similar speech restrictions—laws that generally banned (to quote the relevant part of the Sedition Act),

false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress …, or the President …, with intent to defame [them] … or to bring them … into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them … the hatred of the good people of the United States.

The Act’s backers stressed that the law (unlike the English common law of seditious libel) was limited to “false” and “malicious” statements; and they noted the importance of restricting those statements. Here is Justice Chase’s instruction to the jury in U.S. v. Cooper, about the Sedition Act specifically:

If a man attempts to destroy the confidence of the people in their officers, their supreme magistrate, and their legislature, he effectually saps the foundation of the government.

And here is one from Justice Iredell in Case of Fries, dealing with a treason prosecution arising out of the Fries Rebellion in Pennsylvania in 1799; Iredell was defending the Sedition Act of 1798, though Fries wasn’t tried under that Act:

Ask the great body of the people who were deluded into an insurrection in the western parts of Pennsylvania, what gave rise to it? They will not hesitate to say, that the government had been vilely misrepresented, and made to appear to them in a character directly the reverse of what they deserved.

In consequence of such misrepresentations, a civil war had nearly desolated our country [I believe this refers to the Whiskey Rebellion -EV], and a certain expense of near two millions of dollars was actually incurred, which might be deemed the price of libels, and among other causes made necessary a judicious and moderate land tax, which no man denies to be constitutional, but is now made the pretext of another insurrection.

The liberty of the press is, indeed, valuable—long may it preserve its lustre! It has converted barbarous nations into civilized ones—taught science to rear its head—enlarged the capacity-increased the comforts of private life—and, leading the banners of freedom, has extended her sway where her very name was unknown. But, as every human blessing is attended with imperfection, as what produces, by a right use, the greatest good, is productive of the greatest evil in its abuse, so this, one of the greatest blessings ever bestowed by Providence on His creatures, is capable of producing the greatest good or the greatest mischief….

Men who are at a distance from the source of information must rely almost altogether on the accounts they receive from others. If their accounts are founded in truth, their heads or hearts must be to blame, if they think or act wrongly. But, if their accounts are false, the best head and the best heart cannot be proof against their influence; nor is it possible to calculate the combined effect of innumerable artifices, either by direct falsehood, or invidious insinuations, told day by day, upon minds both able and virtuous.

Such being unquestionably the case, can it be tolerated in any civilized society that any should be permitted with impunity to tell falsehoods to the people, with an express intention to deceive them, and lead them into discontent, if not into insurrection, which is so apt to follow? It is believed no government in the world ever was without such a power….

Combinations to defeat a particular law are admitted to be punishable. Falsehoods, in order to produce such combinations, I should presume, would come within the same principle, as being the first step to the mischief intended to be prevented; and if such falsehoods, with regard to one particular law, are dangerous, and therefore ought not to be permitted without punishment—why should such which are intended to destroy confidence in government altogether, and thus induce disobedience to every act of it?

It is said, libels may be rightly punishable in monarchies, but there is not the same necessity in a republic. The necessity, in the latter case, I conceive greater, because in a republic more is dependent on the good opinion of the people for its support, as they are, directly or indirectly, the origin of all authority, which of course must receive its bias from them. Take away from a republic the confidence of the people, and the whole fabric crumbles into dust….

Gov. Inslee’s argument seems to me to be implicitly premised on the same sort of concern; though the proposed bill would apply to only a particular subset of such “seditious libel” (lies about the supposed corruption or invalidity of elections, rather than lies about the government broadly), it is concerned precisely with the danger that such lies will undermine the government’s credibility and perceived legitimacy, and thus lead to violence or even rebellion.

Again, these concerns are serious concerns, held by serious leaders during the Framing Era. But I think that our legal system has rightly retreated from punishing such seditious libels, partly because criminalizing even outright lies (“false” and “malicious” statements) about the government

- unduly risks suppressing or at least deterring even legitimate opinion,

- unduly risks suppressing allegations that would ultimately prove accurate, and

- unduly risks selective enforcement by officials of that government.

For an example of these problems, see U.S. v. Cooper itself; and the Supreme Court recognized this in 1964, concluding that:

Although the Sedition Act was never tested in this Court, the attack upon its validity has carried the day in the court of history. Fines levied in its prosecution were repaid by Act of Congress on the ground that it was unconstitutional…. The invalidity of the Act has also been assumed by Justices of this Court. These views reflect a broad consensus that the Act, because of the restraint it imposed upon criticism of government and public officials, was inconsistent with the First Amendment….

[Though false, malicious allegations against specific public officials may be punished,] “no court of last resort in this country has ever held, or even suggested, that prosecutions for libel on government have any place in the American system of jurisprudence.”

Likewise, the Washington Supreme Court struck down state statutes that ban lies in election campaigns (whether about initiatives, 119 Vote No! Committee, or candidates, Rickert). The concern in such cases is with fraud on the voters, rather than loss of public confidence in the government, and courts are more split on those. Compare In re Chmura (Mich. 2000); State v. Davis (Ohio App. 1985) (both upholding such election lie statutes) with Susan B. Anthony List v. Driehaus (6th Cir. 2016); 281 Care Comm. v. Arneson (8th Cir. 2014); Commonwealth v. Lucas (2015); and the two Washington Supreme Court cases (all striking them down). (I also think that laws that ban lies about the mechanics of voting, aimed at duping people about when, where, and how to vote, may be constitutional, because they focus on narrow and easily ascertainable questions, and because they aren’t essentially aimed at protecting the government’s reputation.)

But the important thing is that the Washington decisions reaffirmed the impropriety of the punishment of seditious libel: They stressed, with New York Times v. Sullivan, that “the Sedition Act of 1798, which censored speech about government, has been subject to nearly unanimous historical condemnation,” and rejected laws that generally ban lies about “government affairs” that “coerce[] silence by force of law and presuppose[] the State will ‘separate the truth from the false’ for the citizenry…. The First Amendment exists precisely to protect against laws … which suppress ideas and inhibit free discussion of governmental affairs.”

Again, I agree that lies about the government—whether about election results, police abuse, or many other subjects—can at times lead, have at times led, and will at times lead to criminal violence. But American First Amendment precedents take the view that it’s still more dangerous to allow the government to punish speech on the grounds that it might damage the government’s credibility or legitimacy and thus lead to such crime (even speech that prosecutors, judges, and juries find to be knowingly false).

The post Seditious Libel, Today and 225 Years Ago appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3zFRuwF

via IFTTT

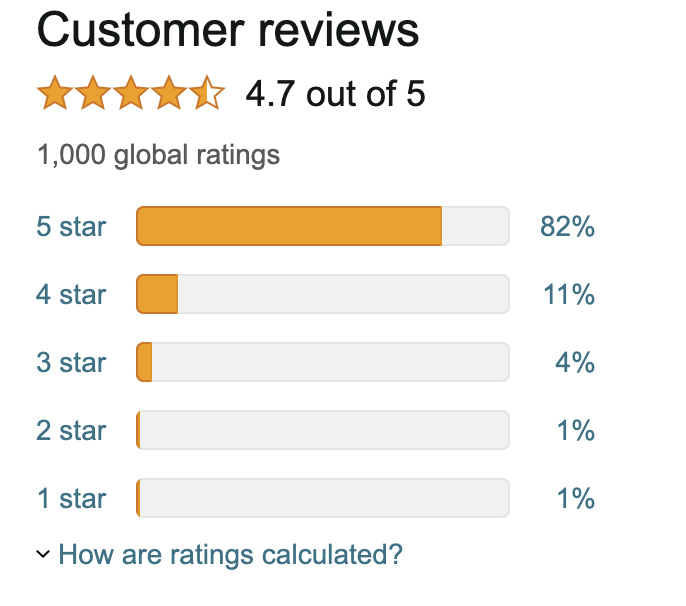

To put this number in perspective, the runner-up book in the Constitutional Law category on Amazon has 652 reviews, and it was released in 2018. And Erwin Chemerinsky’s treatise, which was also released in 2019, has 216 reviews. Our book stands heads and shoulders above the competition.

To put this number in perspective, the runner-up book in the Constitutional Law category on Amazon has 652 reviews, and it was released in 2018. And Erwin Chemerinsky’s treatise, which was also released in 2019, has 216 reviews. Our book stands heads and shoulders above the competition.