There’s not a lot of bipartisanship these days, and legislative efforts around COVID-19 are no different. One exception: Over the last year, both major political parties have shown a like-minded affinity for sneaking policy prescriptions into pandemic relief packages that have little or nothing to do with the pandemic.

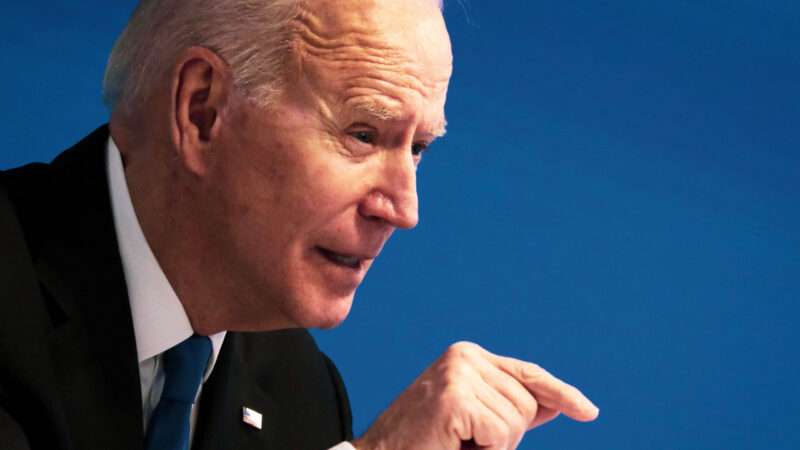

The most glaring example in President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 legislation is arguably the $15 federal minimum wage, which seems to have met its demise at the hands of the Senate parliamentarian. But there’s another subtle measure that has flown under the radar.

It shouldn’t. The bill gifts federal employees up to 15 weeks of paid leave if their lives have been impacted in various ways by COVID-19.

Some of the hall passes laid out in the bill are relatively benign: For example, those “experiencing symptoms of COVID-19 and seeking a medical diagnosis” qualify. Yet that list gets longer and more convoluted. Most notably, it includes any federal worker with children in places where schools are closed—including in areas where there is a mix of virtual and in-person instruction.

That applies to those “caring for a son or daughter of such employee if the school or place of care of the son or daughter has been closed, if the school of such son or daughter requires or makes optional a virtual learning instruction model or requires or makes optional a hybrid of in-person and virtual learning instruction models, or the child care provider of such son or daughter is unavailable, due to COVID–19 precautions,” reads the bill. It also includes government employees who are “experiencing any other substantially similar condition,” though the legislation does not describe what exactly that entails.

Based on the data, the carveout would cover quite a few employees, including every federal worker in Washington, D.C., where residents are currently operating under a partial school closure order.

One problem bears addressing first. Millions of parents across the country are struggling with how to financially support their families while also assuming the role of teacher, test proctor, and Zoom technical support. The poor are bearing the brunt of that—those working low-wage jobs who cannot tune in virtually from their dining room tables. In most cases, it is not federal employees, who on average earn about $110,000 a year, in need of such aid.

Then there’s that glaring question: Just how relevant is this measure? On its face, it checks off the COVID-19 box. But it also comes with a dose of strategic politicking. Democrats have long fought for a paid sick leave program. As I reported almost exactly a year ago, the House’s first coronavirus relief bill included a permanent paid leave package, including for victims of stalking and domestic violence—a well-intentioned goal that was utterly divorced from anything to do with COVID-19. The new provision has been watered down, massaged, and married to the pandemic, but I’d venture to say that’s a means to an end, at least to an extent.

That a 106 percent increase in the federal minimum wage was also marketed as direct COVID-19 relief is instructive. People hurt by the pandemic need higher wages, the thinking goes. That thinking fails to account for the millions of people projected to lose their jobs, should that policy take shape—a policy that would obviously long outlive the pandemic. There’s also the $350 billion that Biden wants to give to states hurt by pandemic woes, including those running a budget surplus. (To be clear, Republicans are not immune to this phenomenon, as evidenced by the billions of dollars allotted for new weapons in their summer relief bill. Let’s blow up the coronavirus!)

And, perhaps most importantly, there’s something distinctly cronyistic about the measure. There’s the obvious bit—they’re federal government employees receiving an exclusive handout from the federal government. But there’s also the notion that it might give Biden himself a handout. That wouldn’t come in the form of paid leave. Rather, it would come in time bought on addressing school closures, something he pinpointed as one of his foremost priorities upon taking office.

“Biden ran on reopening most schools for in-person instruction within a hundred days—a promise his administration has both walked back and then kinda-sorta attempted to un-walk back,” writes Reason‘s Peter Suderman. “But reopening, he has insisted, is conditioned on schools obtaining sufficient funding in a relief package. Accordingly, his plan includes about $128 billion for K-12 schooling ‘or preparation for, prevention of, and response to the coronavirus pandemic or for other uses allowed by other federal education programs,’ as part of a $170 billion boost in education-related spending.”

Even more fraught is that schools already have $100 billion leftover from past COVID-19 aid legislation. They have to spend that money first, meaning that it will be years before they will see the bulk of the additional funding Biden is pushing for. Translation: Schools cannot open in the near future until they receive billions more that won’t be used…in the near future. In full-circle fashion, it appears to be another measure potentially meant to outlast the pandemic.

The paid leave program is not one of those policies. Federal employees who meet the eligibility requirements have until September 30, 2021, to take advantage—enough to get them through the end of the school year.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2OqO6C0

via IFTTT