[This post was co-authored by Josh Blackman and Seth Barrett Tillman.]

On Tuesday, February 9, 2021, the House Managers filed a Reply Memorandum. The Managers’ Reply Memorandum made six primary arguments concerning the First Amendment. Here, we will respond to these arguments.

First, the Managers’ Reply Memorandum referenced a recent letter signed by 140+ academics. The Reply Memorandum asserted:

In the words of nearly 150 First Amendment lawyers and constitutional scholars, President Trump’s First Amendment defense is “legally frivolous.”

Blackman previously explained why the academics’ letter is problematic. The signatories take conflicting positions about how exactly (if at all) the First Amendment should apply to these impeachment proceedings. For example, the academics’ letter states:

“Many of us believe that the First Amendment simply does not apply here [in the impeachment context].”

Many? How many? Is many most? A majority? A plurality? A minority? The academics’ letter does not say.

Indeed, some of the signatories may in fact agree with our position about the relevance of the Brandenburg standard to the article of impeachment. What, then, was “legally frivolous”? Blackman explained:

The introductory section [of the academics’ letter] strikes a chord of unanimity. But it isn’t clear that all of the signatories agree on a single rationale of why a First Amendment defense would be “frivolous.”

It is not clear why the signatories believe a First Amendment defense is, in their view, “frivolous.” More importantly, it is not clear they all actually do believe it is “frivolous.” We expect that if there was no dissent among the signatories, the academics’ letter would have expressed that unanimity clearly. If there was dissent, then the academics’ letter should fully inform the reader as to the basis of that dissent. Instead, the Managers, and the press, only needed to quote the word “frivolous.”

Moreover, the academics’ letter fails to address important evidence that the First Amendment applies to impeachment proceedings. We have discussed the record from President Johnson’s impeachment trial. And our writings were very much in-line with what other scholars wrote prior to the events January 6, 2021.

Second, the Managers’ Reply Memorandum turns to the Johnson impeachment trial. The Managers wrote:

In fact, the Senate has confirmed that the First Amendment does not limit its power to convict in an impeachment proceeding. . . . No precedent supports President Trump’s contrary view. [Trump’s brief] cites the impeachment of President Johnson in 1868, contending that the Senate there established that a President cannot be convicted and disqualified based on his speech. But the Senate set no such precedent in President Johnson’s impeachment. As President Trump notes, one of the articles of impeachment [Article 10] charged President Johnson with insulting and denouncing Congress by “mak[ing] and declar[ing] … certain intemperate, inflammatory, and scandalous harangues … [which] are peculiarly indecent and unbecoming in the Chief Magistrate of the United States.” While some Senators expressed concern that President Johnson’s remarks were constitutionally protected, [FN72] others disagreed. Senator Jacob Howard, for example, stated that “[n]o question of the ‘freedom of speech’ arises here.” [FN73] (emphasis added).

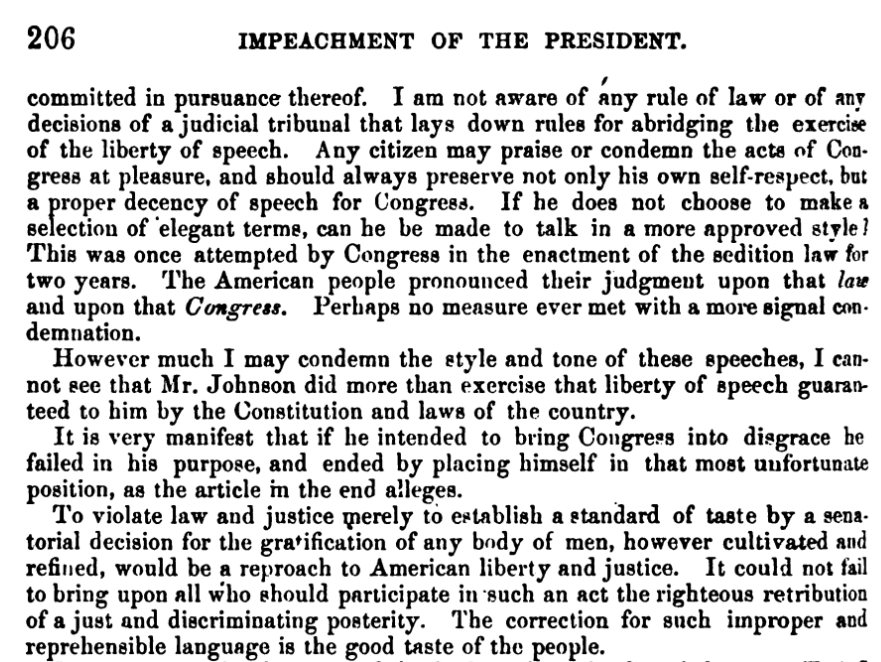

FN72: 3 Trial of Andrew Johnson 206 (1868) (speech of Sen. Joseph Fowler).

FN 73: Id. at 49 (speech of Sen. Jacob Howard).

This passage is problematic. It states, without any equivocation, that there is “no precedent.” But the Managers do not explain what precisely they believe counts as a “precedent” in the impeachment context. In the judicial context, there is wide-ranging disagreement about what precisely constitutes a “precedent.” In the impeachment context, this issue is even more contested. We acknowledge that there is no single view about what counts “precedent” for the impeachment process. There are a multitude of ways to answer this question reasonably. But the House managers do not even countenance this reasonable range of views.

We think the Managers were wrong to make such an unqualified statement: there is “no precedent.” Indeed, they cite evidence that undermines this bold assertion. For example, Footnote 72 cites a statement made by Senator Joseph Fowler who stated that President Johnson could raise the First Amendment as a defense in the impeachment process. He said, “However much I may condemn the style and tone of these speeches, I cannot see that Mr. Johnson did more than exercise that liberty of speech guaranteed to him by the Constitution and laws of the country.”

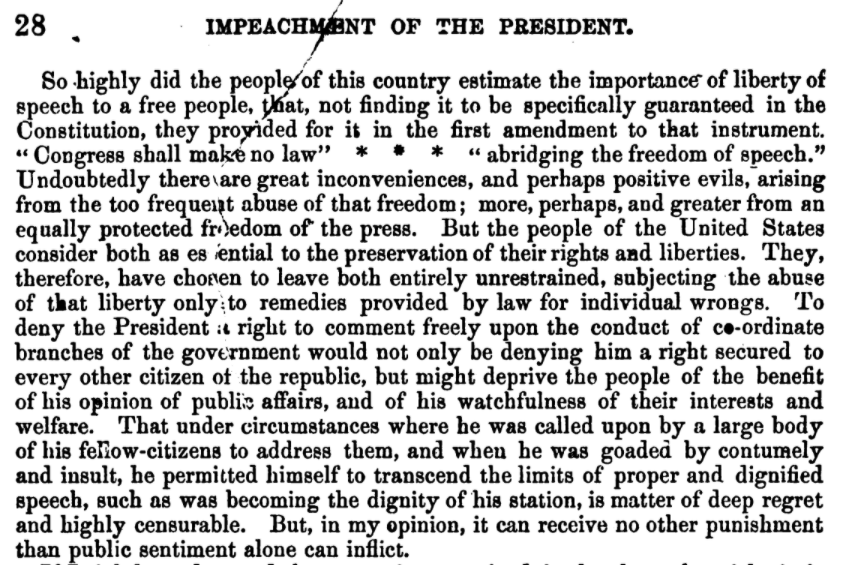

Prominent members of the Reconstruction Congress agreed with Fowler, and argued that Johnson could raise the First Amendment as a defense. Furthermore, Senator William Pitt Fessenden of Maine warned that removing the President for his speech would not only “den[y] him a right secured to every other citizen of the republic . . . but might deprive the people of the benefit of his opinion of public affairs.” The President, Fessenden contended, has the right to communicate with the People. Fessenden chaired the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which drafted what became the Fourteenth Amendment. We would wager that Senator Fessenden’s knowledge of the impeachment process was substantial—every bit as substantial as the signatories of the academics’ letter. Senator Fessenden’s position is not “frivolous.”

Our position has never been that Senator Fessenden stated the only position about the propriety of a First Amendment defense in the impeachment context. But his statements, and those of his colleagues, rebuts the position in the academics’ letter that the First Amendment is inapplicable in impeachment proceedings and is a “frivolous” argument. Moreover, Senator Fessenden’s view has continued into the modern era. In his classic book about presidential impeachments, Grand Inquests, Chief Justice Rehnquist observed that, during times of conflict, “[p]rovisions in the Constitution for judicial independence, or provisions guaranteeing freedom of speech to the President as well as others, suddenly appear as obstacles to the accomplishment of the greater good.” The Chief Justice was right.

Third, the Managers do not care what Senator Jacob Howard, Senator William Pitt Fessenden, or anyone else said during Johnson’s Senate impeachment trial. The Managers’ Reply Memorandum states that because the Senate never voted on Article 10, no precedent was set.

Ultimately the Senate never voted on the article and thus made no judgment about the relevance of the First Amendment.

This argument takes a cramped view of congressional practice in the impeachment context. First, there was a good reason why the Senate did not vote on Article 10. Earlier in the proceedings, the Senate failed to produce a conviction on Articles 2, 3, and 11. These articles, which concerned President Johnson’s removal of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, were viewed as the stronger charges. After Johnson was acquitted on those three charges, the Senate recognized that convictions on the weaker charges were unlikely. As a result, there was a general agreement to terminate proceedings. The House’s failure to secure a conviction in the Senate reduces the claim that the House’s articles of impeachment are good precedents. How “reduced” is a matter about which reasonable minds can, have, and do disagree.

Indeed, the Managers’ cramped view of congressional practice reminds us of Justice Scalia’s long-standing criticism of legislative history. Justice Scalia argued that Congress can only act through voting on a statute. Therefore, courts should ignore legislative history because Congress does not vote on it. And Justice Scalia was loath to consider the legislative history of statutes that were never enacted. According to the Managers, unless the Senate actually votes on an article, the deliberations over that article can be discarded. Justice Scalia’s views may make some sense in the context of run-of-the-mill dispute over statutory interpretation. But we should be more solicitous of Senate presidential impeachment deliberations, which are exceptional. Indeed, Senate precedent is routinely built on practices that do not lead to a final vote. Before President Trump was inaugurated, our nation had two presidential impeachment trials in two centuries. Every aspect of those proceedings have been carefully studied and reviewed in scholarship and judicial proceedings. Everyone has always thought that it was proper to do so. House and Senate impeachment proceedings are not akin to mere committee reports prepared by unknown staffers for a bill. The House and Senate regularly reproduce impeachment debates in their documents on congressional history, practice, and impeachment.

The speeches of prominent Republicans who voted to acquit President Johnson cannot be dismissed as non-sequiturs. These carefully-considered views are not “frivolous” or irrelevant to understanding the impeachment process. There was a time when those votes were considered “profiles in courage.” Now we are told by the Managers that those records are not relevant to understanding how impeachment works. That view is not and cannot be correct.

Fourth, the Managers present something of an alternative argument: even if the First Amendment applies to the proceedings, then President Trump’s speech would be deemed “incitement” under the Brandenburg standard: Later in this post, we will explain why the Managers are precluded from bringing this sort of lesser-included charge. Here, we will discuss why Trump’s speech would be protected by the Brandenburg standard.

The Managers wrote:

In Brandenburg v. Ohio, the Supreme Court explained that, while the First Amendment prohibits states from punishing “mere advocacy,” it does not preclude punishment for speech that is “is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” President Trump’s speech falls squarely within this exception for incitement. His statements on January 6, particularly in the context of his prior remarks, were “directed to” and “likely to incite or produce” imminent unlawful action. President Trump incited a crowd to go to the Capitol and fight, immediately before they stormed the Capitol. (emphasis added).

We emphasized the phrase, “particularly in the context of his prior remarks.” We suggest the Managers recognize that Trump’s January 6, 2021 speech, by itself, cannot meet the Brandenburg standard. Rather, they need to bring in “prior remarks.” Which remarks, the Managers do not say. How old can those remarks be? Would the Managers consider everything Trump has ever said? Or do they mean to consider only the things Trump has said since the election? Or just statements he made since the election concerning the election? Alas, Brandenburg does not permit any of these expansive approaches. The focus on “imminence” counsels against such a sweeping probe of any past statements that could shed light on the purported “context” of the January 6.

On February 10, 2021, Adam Liptak wrote a commentary in the New York Times breaking down another Trump case concerning incitement.

. . . . Judge David J. Hale of the Federal District Court in Louisville, Ky., allowed a[n incitement] lawsuit against [Trump] to proceed, writing that incitement is a capacious term. Quoting Black’s Law Dictionary, he wrote that it was defined as “‘the act or an instance of provoking, urging on or stirring up,’ or, in criminal law, ‘the act of persuading another person to commit a crime.'”

Judge Hale also wrote that the protesters could satisfy the demanding First Amendment limits the Supreme Court had placed on incitement suits. . . . .

Judge Hale said the account of the rally presented in the protesters’ lawsuit could clear the high [Brandenburg] bar. “It is plausible that Trump’s direction to ‘get ’em out of here’ advocated the use of force,” the judge wrote. “It was an order, an instruction, a command.”

He added that the protesters had, at least at an early stage of the litigation, plausibly maintained that Mr. Trump had “intended for his statement to result in violence” and “was likely to result in violence.”

But the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, in Cincinnati, reversed Judge Hale’s decision, ruling that the Brandenburg decision protected Mr. Trump. “In the ears of some supporters, Trump’s words may have had a tendency to elicit a physical response, in the event a disruptive protester refused to leave,” Judge David W. McKeague wrote for the majority, “but they did not specifically advocate such a response.” It was significant, too, Judge McKeague wrote, that Mr. Trump had added a caveat to his exhortation, according to the lawsuit. “Don’t hurt ’em,” Mr. Trump said. “If I say ‘go get ’em,’ I get in trouble with the press.”

Mr. Trump offered a similarly mixed message on Jan. 6. Even as he urged his supporters to “go to the Capitol” and “fight like hell,” he also made at least one milder comment. “I know that everyone here will soon be marching over to the Capitol building to peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard,” he said.

Ordinary courts might consider the speech in isolation and credit the occasional calmer passage.

The Managers do not cite any incitement case that permits consideration of the “context of his prior remarks” in such an expansive fashion. If the Managers have such a case, they should bring it forward.

In our fourth point, we explained that the Manager’s alternative argument is not supported by precedent. Brandenburg would not support a criminal conviction for incitement of violence. Our fifth point is more foundational. The House’s article of impeachment does not mention or use the Brandenburg standard to charge the President. A draft version of the article relied on something akin to Brandenburg, but the adopted article removed that standard. Instead, the House made up a standard out of whole cloth: that Trump “willfully made statements that, in context, encouraged—and foreseeably resulted in—lawless action at the Capitol.”

The House chose that standard—they have nailed their colors to the mast. And that decision now binds the House, the Managers, and the Senate. Given the sole article of impeachment, the Managers are precluded from raising an alternate argument based on Brandenburg. In other words, the Managers cannot seek to convict Trump based on some other charge or theory of liability, even one akin to a lesser-included offense.

If the House cannot secure a conviction based on the legal theory it has put forward, then the Managers cannot argue that Trump could still be convicted under other legal theories not alleged in the Article of Impeachment. Here, Trump’s attorneys raised Brandenburg as a defense. The Managers could argue that Brandenburg has no place in the impeachment process. But the Managers are precluded from arguing that the Senators can also convict Trump under Brandenburg, a standard the House chose not to impeach on. In short, it is legally irrelevant whether Trump could be convicted under the Brandenburg standard.

Moreover, the House Managers and the Senate would violate the most basic sense of fair play if they tried and convicted Trump under a theory of liability which does not appear in the article of impeachment It violates conceptions of fair play to try and convict a defendant under a standard that was not charged. Likewise, Trump cannot be asked to put on a defense based on the Brandenburg standard, which the House intentionally dropped from its article of impeachment during the drafting process.

Of course, the House could have decided to impeach Trump based on alternate theories of liability. For example, Article I could have relied on the novel theory the House created. And Article II could have relied on the Brandenburg standard.

Alternatively, the House could have adopted an article of impeachment that expressly reserved the right to draft and exhibit new or revised articles of impeachment. There is a long-standing tradition of such open-ended articles of impeachment that expressly reserve the right to exhibit new articles of impeachment. Indeed, the English Parliament was already using this practice more than three centuries ago. For example, the House of Commons’ articles of impeachment against Lord Somers (circa) 1701 reserved the right of “exhibiting, at any time hereafter, any further articles” in the trial proceedings before the House of Lords. This phrase allowed the House of Commons to introduce new articles of impeachment.

This exact language, or something very close to it, was also used in each of the antebellum American impeachment trials: i.e., the Senate impeachment trials of Senator Blount, Judge Pickering, Justice Chase, and Judge Peck.

Article 9 in the Johnson Impeachment Trial used very similar language:

and the House of Representatives, by protestation, saving to themselves the liberty of exhibition, at any time hereafter, any further articles of their accusation or impeachment against the said Andrew Johnson, President of the United States

Even managers of state impeachments on the American frontier knew enough to make such a reservation. The Impeachment of Nebraska Governor Butler in 1871 used this language. However, the rushed article of impeachment adopted in January 2021 did not use this language. At this point, we have doubts that the House could introduce new articles of impeachment based on this same course of conduct. Moreover, adding new articles in the future would trigger a new unresolved late-impeachment question: can a former officeholder be impeached under revised articles of impeachment when he is already out of office, after having been impeached once while still in office, absent any reservation by the House to “replead.”

At this juncture, the Managers are stuck with the single article adopted by the House. If the House chooses an improper, legally defective standard, then no legally sufficient wrong has been alleged. In other words, there is no case to answer. We think these circumstances would resemble a prosecutor’s indictment based on a violation of a non-existent crime. Given the House’s defective “indictment,” Senators could vote to acquit on these grounds.

Sixth, the Managers respond to an argument that we have advanced, and which Trump’s attorneys have adopted: different types of officeholders have different degrees of free speech rights. The Managers write:

These statements [by Trump] would not be protected whether they were made by an elected official, a civil servant, or a private citizen—contrary to President Trump’s lengthy argument that those distinctions should matter.

All three branches of government have long recognized the distinctions between civil servants, senior appointed officers, and elected officials. We didn’t make these distinctions up. Look no further than the Hatch Act. The statute applies to civil servants and to appointed officers. But the President is exempt from this ban on politicking. Why? Why are elected members of Congress also exempt from this ban? This distinction is well-understood and deeply rooted in American law. If the Managers have any authority to the contrary, they should cite it.

Next, the Managers turn to a U.S. Supreme Court case: Wood v. Georgia (1981) (Warren, C.J.). The Managers’ Reply brief states:

President Trump is not helped by his reliance on a case concerning punishment for statements made by an elected official “as a private citizen” that “did not present a danger to the administration of justice.”FN78

FN78: See Wood, 370 U.S. at 382, 393, 395.

A pro tip for law students: when a citation includes quotes strung out across non-consecutive pages, check if the quotations are taken out of context. The House managers made this precise error.

The Managers’ Reply Memorandum citation to Wood v. Georgia refers to 3 pages: 382, 393, and 395.

First, page 382 includes this passage:

. . . the statements were made by petitioner in his capacity as a private citizen and not as sheriff of the county; that petitioner was directly and personally interested in the outcome of the current primary election not only as a private citizen but also as an announced candidate for public office in the general election to be held the following November, and in which election the petitioner would be running against the contestant who prevailed in the democratic primary. . . . (emphasis added)

Second, the Managers’ Reply Memorandum cites page 393. But it does not quote anything on that page. And it is not at all clear what, if anything, the House Managers believe is relevant from that page.

Third, page 395 includes this passage:

Our examination of the content of petitioner’s statements and the circumstances under which they were published leads us to conclude that they did not present a danger to the administration of justice that should vitiate his freedom to express his opinions in the manner chosen. (emphasis added)

The passage on 382 about a “private citizen” did not affect the Court’s analysis, thirteen pages later, about a “danger to the administration of justice.” It isn’t clear why the Managers strung together these two points.

Moreover, the Petitioner in Wood v. Georgia was also a “candidate for public office” who gave the speech “as a private citizen.” We have argued that Trump’s speech at the Ellipse was not made in his capacity as a public official, but was, essentially, a private act. In giving that speech, Trump did not make use of government information, property, personnel, or powers that were entrusted to him by virtue of his former public position. Wood v. Georgia, as applied to the facts of January 6, 2021, provides even more support for our position: Trump’s First Amendment free speech rights are relevant to the impeachment inquiry.

The Managers also consider another Supreme Court decision: Bond v. Floyd (1966) (Warren, C.J.). The Managers’ Reply Memorandum states:

Nor does the Supreme Court’s recognition that an elected legislator could not be excluded from state office for “criticizing public policy” advance President Trump’s claim, where the Court distinguished that situation from one in which “a legislator swears to an oath pro forma while … manifesting his … indifference to the oath.”FN79 President Trump’s speech was not a criticism of public policy—rather, it was a repudiation of his oath of office as he incited a violent insurrection and then manifested callous indifference to its deadly consequences.

FN79: Bond, 385 U.S. at 132, 136.

Here too, the Managers strung out quotes that span several pages. Likewise, the Managers’ use of ellipses alters the meaning of a passage from Chief Justice Warren’s opinion.

First, the Bond passage on page 132 states:

The State argues that the exclusion does not violate the First Amendment because the State has a right, under Article VI of the United States Constitution, to insist on loyalty to the Constitution as a condition of office. A legislator of course can be required to swear to support the Constitution of the United States as a condition of holding office, but that is not the issue in this case, as the record is uncontradicted that Bond has repeatedly expressed his willingness to swear to an oath provided for in the State and Federal Constitutions. Nor is this a case where a legislator swears to an oath pro forma while declaring or manifesting his disagreement with or indifference to the oath. Thus, we do not quarrel with the State’s contention that the oath provisions of the United States and Georgia Constitutions do not violate the First Amendment. (emphasis added).

Second, the brief cites to page 136 of Bond. Here is the passage, which begins on page 135:

But this difference in treatment does not support the exclusion of Bond, for while the State has an interest in requiring its legislators to swear to a belief in constitutional processes of government, surely the oath gives it no interest in limiting its legislators’ capacity to discuss their views of local or national policy. The manifest function of the First Amendment in a representative government requires that legislators be given the widest latitude to express their views on issues of policy. The central commitment of the First Amendment, as summarized in the opinion of the Court in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254, 270 (1964), is that “debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.” We think the rationale of the New York Times case disposes of the claim that Bond’s statements fell outside the range of constitutional protection. Just as erroneous statements must be protected to give freedom of expression the breathing space it needs to survive, so statements criticizing public policy and the implementation of it must be similarly protected. (emphasis added).

The Managers contend that Trump’s speech at the Ellipse was “manifesting his . . . indifference to the oath.” That is, Trump was violating his oath of office. Therefore, the argument goes, Trump does not receive the First Amendment rights associated with “criticizing public policy.” In other words, the Managers argue that when the President violates his oath of office, he has reduced Free Speech rights. Chief Justice Warren’s discussion in Bond was not referring to an officeholder whose actions conflict with his oath. Rather, the passage concerns whether the imposition of the oath itself violates the First Amendment:

Nor is this a case where a legislator swears to an oath pro forma while declaring or manifesting his disagreement with or indifference to the oath.

On page 132, Chief Justice Warren speculated about an alternative case where the officeholder spoke about his “disagreement” with his oath. Imagine that an officeholder takes the oath with his fingers crossed to express a “disagreement” with the oath. Or the officeholder swears the oath, and immediately repudiates, and disagrees with that oath. Or the officeholder swears an oath with his hand placed on a copy of the now-defunct Mad Magazine. We think Chief Justice Warren’s counterfactual was fairly straightforward.

However, the Managers use ellipses to omit a critical word from Bond: “disagreement.” The Managers were trying to convey a different point: that Bond was about conduct that amounted to “indifference” to the oath. That is, conduct that violated the oath itself. The quoted passages from Bond did not articulate the Managers’ point. Instead, those passages from Bond concerned a public official’s expression of “disagreement with or indifference to” the content of the oath itself. There is a world of difference between these two positions: violating an oath, and disagreeing with the contents of an oath. The latter position cannot be converted to the former position through the use of ellipses.

[Seth Barrett Tillman is a Lecturer at Maynooth University Department of Law, Ireland (Roinn Dlí Ollscoil Mhá Nuad).]

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2Z9pyzW

via IFTTT