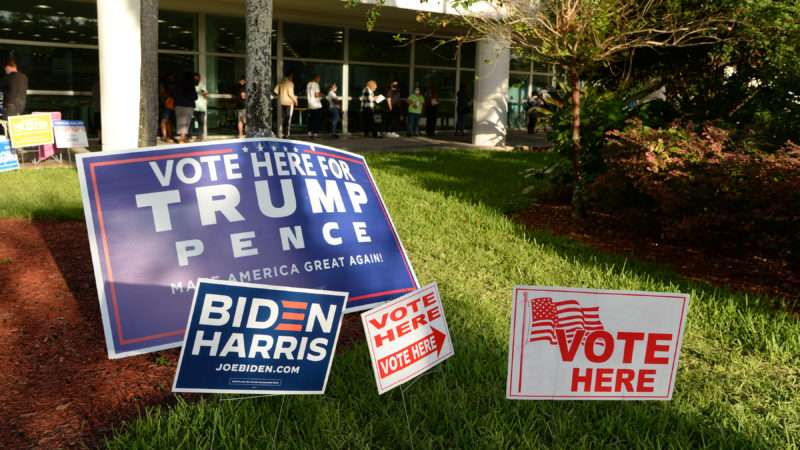

From the Allegheny Plateau to the Florida coast to the wide-open spaces of the Upper Midwest, President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden will spend the last weekend of the 2020 presidential campaign crisscrossing the country in search of the last remaining undecided voters.

Trump, who trails in the (meaningless) national polls but seems to have a narrow path to victory in the Electoral College, plans to hold 11 rallies between now and Election Day, according to NBC News. He’ll spend Friday at rallies in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, then will hold a series of three events in different parts of Pennsylvania on Saturday. Stops in North Carolina and Florida on the final days of the campaign seem likely, though details remain sketchy for now.

Biden has run a low-key campaign in contrast to the president’s high-profile public rallies—the challenger has left his home state of Delaware just three times in the past 10 days, The New York Times notes—but will make visits to Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin on Friday. He will spend Sunday in Pennsylvania.

The contrasting campaign styles match the tone of the two major candidates and reflect, to some extent, their closing messages to voters. That’s especially true when it comes to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been the dominant story of the campaign and the year. As he has been for months, Trump is pushing the message that America is winning its battle against the disease, and that advances in treating COVID-19 mean precautions like social distancing and mask wearing are not necessary. Biden’s more timid schedule recognizes the risks, particularly for individuals as old as the two candidates. “It’s important to be responsible,” Biden told The New York Times this week when asked about his slow campaign schedule.

This has really never been a campaign about policy—Trump has had a difficult time articulating a second-term agenda even when asked about it by friendly media, while Biden has luxuriated in simply being the anti-Trump.

Both men are likely to offload a significant portion of their agenda-setting to lieutenants, but that’s not necessarily great news. Senior White House adviser Stephen Miller on Thursday outlined plans for even more restrictive immigration rules if Trump is reelected, including “limiting asylum grants, punishing and outlawing so-called sanctuary cities, expanding the so-called travel ban with tougher screening for visa applicants and slapping new limits on work visas,” NBC News reported.

Meanwhile, Politico reported that Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) is seeking to become Biden’s Treasury secretary if he prevails. That would put her in a position to be one of the administration’s leading voices for setting economic policy—but her ideas don’t add up.

Unfortunately, those of us who believe in the unfettered movement of people and money don’t have much to get excited about in these final days of the campaign.

The political version of hell is scheduled for next Wednesday, when Dems are freaking out (and GOPers rejoicing) over vote totals that show Trump with large leads in Upper Midwestern states – but it's a mirage b/c millions of mail ballots have yet to be counted.

— Dave Wasserman (@Redistrict) October 29, 2020

Keep in mind that it’s unlikely we’ll know the outcome of the election on Tuesday night. In the key swing state of Pennsylvania, some counties won’t even begin counting their piles of absentee ballots until Wednesday. The ultimate irony of the 2020 campaign is that a record number of votes have already been cast—more than 75 million—before the candidates hit the homestretch, but that all those early votes will translate into later-than-expected results.

Those early votes also change the dynamic of the campaign’s final weekend. Instead of a last-minute appeal to would-be supporters (most of whom are already locked in), it’s a battle for the souls of Pennsylvanians and Floridians who just now realized there’s an election on Tuesday.

FREE MINDS

Don’t buy Biden’s message about the Violence Against Women Act, which he frequently brags about helping to write when he was a member of the Senate, writes Reason’s Elizabeth Nolan Brown:

Biden’s role in all of this may indeed reflect a genuine desire to help women. But it also reflects his longtime role as Democrats’ for-better-or-worse standard-bearer—the party operator willing to go all-in on whatever centrist ideas have captured the zeitgeist and to give a folksy, do-gooder veneer to all sorts of ultimately ugly policies. In the years since, he has moved seamlessly from mischaracterizing fears about domestic violence to backing counterproductive and ineffective responses to more modern moral panics, like campus sexual assault. And he has continued to display a tendency for elevating faddish interpretations of progressive feminist advocacy that turn out to infantilize women, driving up their arrest rates and placing them in greater danger—all while portraying himself and the state as their saviors.

FREE MARKETS

Don’t buy Trump’s message about tariffs and protectionism, because the “America First” agenda has failed on just about every possible front, writes the Cato Institute’s Scott Lincicome.

Tariffs didn’t revive America’s steel industry, reports The Wall Street Journal.

And Trump’s trade war didn’t boost the American manufacturing sector, writes Brad Polumbo at the Foundation for Economic Education.

ELECTION 2020

Final days of the campaign lightning round!

A federal appeals court has ruled that Minnesota can’t accept absentee ballots that arrive after Election Day—even the U.S. Supreme Court has allowed, for now, post-election collection of mail-in ballots in North Carolina and Pennsylvania.

NEW: 8th Circuit Court of Appeals rules in Minnesota's absentee ballot deadline case that absentee ballots must be in by 8pm on Election Day.

"There is no pandemic exception to the Constitution."

Court holds out possibility of counting later and says late ballots set aside.

— Brian Bakst (@Stowydad) October 29, 2020

Read The Washington Examiner‘s Tim Carney on the political realignment in western Pennsylvania that has bridged a decades-old political divide between bosses and workers.

Four days before the election, turnout has already exceeded 2016 levels in Hawaii. Big turnout is being reported in the potential swing states of Georgia and Texas too.

Hawaii first state to beat its 2016 turnout: now at 104%

Texas: 95

Washington: 88

Montana: 86

Tennessee: 83

Oregon: 82

North Carolina: 81

Georgia: 82More than 81 million ballots back in hands of election official, per @ElectProject #Election2020

— Ryan Heath (@PoliticoRyan) October 30, 2020

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R–S.C.) has twisted himself into a hypocritical pretzel to defend Trump during the past four years. Now that Graham is in danger of losing his Senate race, Trump seems to be leaving him hung out to dry. You absolutely love to see it.

Graham’s race is one of the most important Senate elections next week.

Libertarian Party presidential nominee Jo Jorgensen is unhappy about being left out (again) despite being on the ballot in all 50 states and being a potential spoiler in a few key places:

Sadly, @Nickelodeon / @NickelodeonPR is complicit in indoctrinating our children that there are only 2 parties, even though there are 3 candidates on all 50 ballots and 4 who can get to 270.

What a shame for America's future, #Nicknews.

This #election, teach your children well. pic.twitter.com/nugVSKu2i2— Jo Jorgensen (@Jorgensen4POTUS) October 25, 2020

Finally, here’s a sign that America’s political state is perhaps a bit more fragile than it should be: Businesses in Washington, D.C., are already boarding up windows in advance of next week’s election.

QUICK HITS

- Civil libertarian journalist Glenn Greenwald resigned from The Intercept, which he founded in 2014, amid claims that he was being “censored” by the publication’s editors, and it quickly turned into an ugly public feud.

- At the request of Turkish dictator Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Trump reportedly squashed a Justice Department investigation into a Turkish bank.

- Chinese authorities arrested a man for reading Wikipedia.

- Can companies lure workers back to offices with free lunches and other goodies?

- New Yorkers are rediscovering the fact that cars are pretty great.

New Yorkers remembering that the reason we have cars is because we love freedom and the car is the greatest symbol of freedom imaginable is the most New Yorker thing I can imagine. https://t.co/1rl4OZXhCo pic.twitter.com/12pZoWpy5Q

— Sonny Bunch (@SonnyBunch) October 29, 2020

- It’s a metaphor for the election, I think?

A New York City man recently fell about 15 feet into a pit of rats when a sidewalk sinkhole opened under his feet https://t.co/Yxd3mMQUpT

— The Cut (@TheCut) October 30, 2020

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/32dSmcv

via IFTTT