Last month, Illinois became the first state in the U.S. to ban police from lying to minors during interrogations. Oregon followed suit shortly after, and similar legislation has been introduced over the past several legislative sessions in New York.

The new laws and bills are the result of years of mounting evidence and DNA exonerations showing that minors and even adults can be pressured by police into falsely confessing to crimes they didn’t commit.

Specifically, Illinois’ law makes confessions by minors obtained through knowing deception about evidence or leniency inadmissible in court. As states begin to finally reckon with the phenomenon of false confessions, there are plenty of cases that show the disastrous consequences of using deception and other ploys to squeeze confessions out of people.

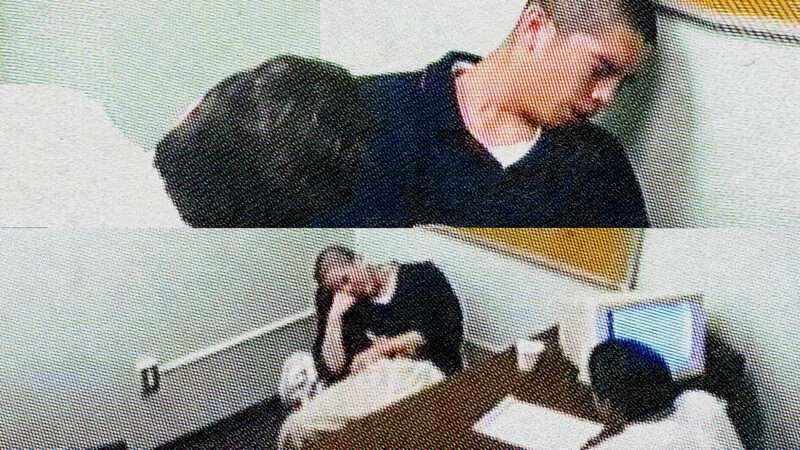

Take the case of Lawrence Montoya. In 2000, Denver police officers took Montoya, then 14 years old, and his mother into a small interrogation room to question him about the death of Emily Johnson, a 29-year-old schoolteacher who had been found fatally injured in her backyard in the early morning hours of New Year’s Day.

Later that day, Montoya hopped in a car with his cousin and some other teens he didn’t know to go joyriding. It was Johnson’s stolen Lexus. Police later found the Lexus in a ditch, and eventually got an anonymous tip about the driver, who’d been running his mouth about stealing it. The driver gave up the names of all the other passengers, including Montoya’s.

In the interrogation room, Montoya admitted to the detectives that he’d taken a ride in the car, but over the course of the next two hours, he denied ever being at the house 65 times. Eventually the detectives got Montoya’s mother to leave, giving them the opportunity to lean on Montoya harder.

“I wasn’t at that lady’s house, bro,” he insisted at one point, by then crying.

“Lorenzo, your footprint is in that blood,” one detective responded. (Montoya now goes by Lawrence.)

“Who kicked her in the head first, Nick or J.R.?” the other detective cut in.

The officers told him there was a small mountain of evidence against him.

“I tell you Lorenzo, if you were there, you better give it up. We’ve got fingerprints, we’ve got blood prints, we’ve got saliva prints,” one said. “We’ve got everything.”

And: “You don’t have a fuckin’ clue what we can prove. Your ass is hanging out big time.”

Montoya sobbed as the detectives continued to yell and pile questions on him. They were the kind of trick questions meant to get you in trouble, such as, “Was she dead when you left her?”

The boy only had one real escape hatch: keep his mouth shut. But after being worn down by hours of threats, suggestions of leniency, and lies about damning physical evidence, even innocent adults will start to rationalize confessing to a crime they didn’t commit. Maybe the cops really will let you go home if you just give them what they want. Surely it will all get sorted out later, when the police realize they have the wrong person.

“Unfortunately what we know is that it rarely does get sorted out later,” says Rebecca Brown, director of policy at the Innocence Project, a nonprofit that works to overturn wrongful convictions. “In fact, even in the face of exculpatory DNA evidence, fact-finders often will trump that evidence with confession evidence. In other words, they will believe the confession over the biological evidence that points elsewhere.”

According to the Innocence Project, nearly 30 percent of exonerations involve false confessions, a number that would have been dismissed as absurd and unthinkable before the advent of DNA testing.

And so, after a long pause, Montoya said, “Was I outside the house? Yes.”

One of the detectives leaned in and softened his voice, no longer yelling or threatening. “Lorenzo, you’re this close to taking a big load off your shoulders,” he said. “An unbelievable load off your shoulders. So just tell us about it. It’s a simple thing.”

Using the facts that the police officers had already revealed or prodded him toward—making sure to correct himself when detectives indicated he got basic facts about the murder wrong—the 14-year-old spun a flimsy story for them. And with that simple thing, Montoya talked his way into a life sentence.

There was no evidence against him, besides his confession and a jailhouse snitch who testified Montoya had told him about his role in the murder when they were in the same cell. (It was later revealed they were never housed together.) None of the other suspects placed him at the house, and all the forensic evidence cited during his interrogation either never existed or was later linked to the other suspects. Nevertheless, a jury convicted him of first-degree felony murder. Montoya spent 13 years behind bars, much of it in solitary confinement because he was a minor in an adult prison, before prosecutors cut a deal to release him on time served in exchange for his pleading guilty to being an accessory after the fact.

In 2016, Montoya filed a still-ongoing federal lawsuit, arguing that the city of Denver and several Denver police officers violated a panoply of his civil rights. His lawyers, David Fisher and Jane Fisher-Byrialsen, also represented one of the defendants in the infamous Central Park Five case.

Montoya’s case is a textbook example of how coercive interrogation techniques, confirmation bias, and corner cutting can lead to a false confession and a wrongful conviction.

It’s also a textbook example of how police in America have mostly conducted interrogations since the late 1960s. The Supreme Court ruled it was lawful for the police to lie during interrogations in 1969, in Frazier v. Cupp, a case where a man challenged his murder conviction on the grounds that police had claimed that the man’s cousin had already confessed and implicated him, which was not true. The Court ruled that the officers’ lies were, “while relevant, insufficient, in our view, to make this otherwise voluntary confession inadmissible.”

Threats, bluffs, and other ploys are all part of the police toolbox now in what’s known as the Reid technique, the dominant method for conducting police interrogations for more than half a century. The Reid technique is guilt-presumptive, meaning the primary purpose is to get suspects to implicate themselves or confess.

Illinois and Oregon’s new laws are part of a major shift in our understanding of how psychological manipulation can create false confessions. Brown says about 30 states now require interrogations to be recorded, and Wicklander-Zulawski & Associates, an interrogation consulting firm that also trains police, announced it would stop using the Reid technique in 2017. Washington passed a law earlier this year requiring attorney consultations for minors before police can interrogate them.

“I hope the Illinois law will serve as a model for other states,” Lawrence T. White, professor emeritus of psychology at Beloit College, wrote in an email to Reason. “In the United Kingdom, police cannot lie to suspects under any circumstances. It’s been that way since the PACE (Police and Criminal Evidence) Act was passed in 1984, 37 years ago.”

John E. Reid and Associates, the firm that created and trains investigators in how to use the Reid technique, argues that false confessions mostly arise out of police not following its methods, which prohibit false promises of leniency, excessively long interrogations, and denials of physical necessities like bathroom breaks. It also urges extra care when interviewing minors and those with developmental disabilities.

But these new laws are an acknowledgment that minors are particularly vulnerable to being manipulated by coercive interrogation techniques.

“Juveniles and young adults confess more readily than older adults because young people are less mature, less likely to have prior experience with law enforcement, less likely to understand their Miranda rights, more likely to waive their Miranda rights, more likely to comply with the demands of authority figures, and less able to resist police pressure,” White says. “They also are more likely to focus on immediate rewards and ignore the long-term consequences of their actions.”

Brown says that about 30 percent of DNA exonerees were under the age of 18 when they falsely confessed, and if you raise that age to 25, it’s 49 percent.

Both White and Brown say there’s no reason not to extend similar protections to adults, who can still be swayed by police lies about evidence and other manipulations.

“The false confession cases that have been discovered surely represent the tip of an iceberg because the 375 DNA exoneration cases do not include cases in which a false confession was disproved before trial,” White says. “They also do not include cases that result in guilty pleas (and cannot be appealed), cases in which DNA evidence was not available, cases (such as minor crimes) that do not receive post-conviction scrutiny, and juvenile proceedings that contain confidentiality provisions.”

In July, California resident Roger Wayne Parker filed a civil rights lawsuit against Riverside County and its former district attorney after he was held in jail for nearly four years based on a murder confession that two prosecutors believed was obviously false and coerced. In fact, one of the line prosecutors wrote a memo outlining why the lack of any matching DNA or fingerprint evidence, and the 15-hour interrogation of Parker, who has an IQ below 80, led her to believe that Parker was innocent.

“I was concerned that the ‘confession’ was given so Roger could get out of jail because they had told him self-defense was legal and denial only landed him in jail,” the prosecutor wrote.

Despite this, the D.A. forged ahead, removing both prosecutors from the case and holding Parker in jail for two and a half more years before finally dropping the case.

The other prosecutor is also suing, saying he was told by superiors to withhold DNA evidence pointing to Parker’s innocence, and then forced out of his job after he defied them.

“You would get just as many confessions and convictions if you did it the right way, instead of lying to people, and you would remove one of the things that contributes to so many false confessions,” says Parker’s attorney, Gerald Singleton.

More states could soon join Illinois and Oregon. Brown said the Innocence Project has received inquiries from lawmakers in Connecticut, Delaware, and Washington state, along with the ongoing efforts in New York. New York’s proposed legislation would extend beyond children to bar police from lying to adults during interrogations.

“We expect this to be a pretty hot issue in the upcoming sessions,” Brown says.

It will also likely be contentious in New York, where police unions hold considerable political sway. Paul DiGiacomo, head of the New York Police Department (NYPD) detectives union, defended deceptive practices in a March interview with the New York Daily News.

“What people often label as trickery is a solid tactic…that detectives use to add evidence already collected,” DiGiacomo said. “There’s nobody who wants to see the right person behind bars more than the dedicated detectives working the case.”

As for Montoya, the city of Denver has fought his lawsuit tooth and nail, claiming the officers involved are entitled to qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that shields public officials who violate someone’s constitutional rights, if that right wasn’t “clearly established” at the time of the violation. Federal courts have dismissed or limited much of Montoya’s suit.

In March, though, a federal judge ruled that some of Montoya’s claims could proceed. The judge noted that Montoya’s so-called confession was riddled with contradictory statements and errors about significant facts of the murder, all of which were fed to him by his interrogators, who then wrote a “dishonest” affidavit that excluded exculpatory evidence and twisted his words.

“The thing to me about this case and cases like it is he’s completely innocent,” says Fisher. “He didn’t do anything wrong. He spent his entire childhood in segregation in an adult prison, and rather than trying to make it right and change the way Denver interrogates children, they’re trying to use legal technicalities to get out of the lawsuit while my client suffers and other people get wrongfully convicted. That’s the thing that really bothers me. Unless there’s pressure put on Denver, they’re just going to keep doing what they’re doing. There’s not much incentive to do the right thing unless people know you’re doing the wrong thing.”

The Denver Police Department did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3jVyC5q

via IFTTT