7/1/1985: Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc. is decided.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2Zv3qiY

via IFTTT

another site

7/1/1985: Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc. is decided.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2Zv3qiY

via IFTTT

Minnesota State Patrol trooper Albert Kuehne has been charged with two counts of felony stalking. Prosecutors say Kuehne responded to a single-car wreck involving a woman detained as a possible drunk driver. They say Kuehne took the woman’s phone and messaged nude photos the woman had of herself on her phone to his own phone while she was being treated by paramedics. Kuehne faces up to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine for each charge.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2YKQK8C

via IFTTT

Minnesota State Patrol trooper Albert Kuehne has been charged with two counts of felony stalking. Prosecutors say Kuehne responded to a single-car wreck involving a woman detained as a possible drunk driver. They say Kuehne took the woman’s phone and messaged nude photos the woman had of herself on her phone to his own phone while she was being treated by paramedics. Kuehne faces up to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine for each charge.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2YKQK8C

via IFTTT

Protesters say America’s criminal justice system is unfair.

It is.

Courts are so jammed that innocent people plead guilty to avoid waiting years for a trial. Lawyers help rich people get special treatment. A jail stay is just as likely to teach you crime as it is to help you get a new start. Overcrowded prisons cost a fortune and increase suffering for both prisoners and guards.

There’s one simple solution to most of these problems: End the war on drugs.

Our government has spent trillions of dollars trying to stop drug use.

It hasn’t worked. More people now use more drugs than before the “war” began.

What drug prohibition did do is exactly what alcohol prohibition did a hundred years ago: increase conflict between police and citizens.

“It pitted police against the communities that they serve,” says neuroscientist Carl Hart in my new video. Hart, former chair of Columbia University’s Psychology department, grew up in a tough Miami neighborhood where he watched crack cocaine wreck lives. When he started researching drugs, he assumed that research would confirm the damage drugs did.

But “one problem kept cropping up,” he says in his soon-to-be-released book, Drug Use For Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear, “the evidence did not support the hypothesis. No one else’s evidence did either.”

After 20 years of research, he concluded, “I was wrong.” Now, he says, our drug laws do more harm than drugs.

Because drug sales are illegal, profits from selling drugs are huge. Since sellers can’t rely on law enforcement to protect their property, they buy guns and form gangs.

Cigarettes harm people, too, but there are no violent cigarette gangs—no cigarette shootings—even though nicotine is more addictive than heroin, says our government. That’s because tobacco is legal. Likewise, there are no longer violent liquor gangs. They vanished when prohibition ended.

But what about the opioid epidemic? Lots of Americans die from overdoses!

Hart blames the drug war for that, too. Yes, opioids are legal, but their sale is tightly restricted.

“If drugs were over the counter, there would be fewer deaths?” I asked.

“Of course,” he responds. “People die from opioids because they get tainted opioids….That would go away if we didn’t have this war on drugs. Imagine if the only subject of any conversation about driving automobiles was fatal car crashes….So it is with the opioid epidemic.”

Drugs do harm many people, but in real life, replies Hart, “I know tons of people who do drugs; they are public officials, captains of industry, and they’re doing well. Drugs, including nicotine and heroin, make people feel better. That’s why they are used.”

President Eisenhower warned about the military-industrial complex. America’s drug war funds a prison-industrial complex. Hart says his years inside the well-funded research side of that complex showed him that any research not in support of the “tough-on-drugs” ideology is routinely dismissed to “keep outrage stoked” and funds coming in.

America locks up more than 2 million Americans. That’s a higher percentage of our citizens, disproportionately black citizens, than any other country in the world.

“In every country with a more permissive drug regime, all outcomes are better,” says Hart. Countries like Switzerland and Portugal, where drugs are decriminalized, “don’t have these problems that we have with drug overdoses.”

In 2001, Portugal decriminalized all drug use. Instead of punishing drug users, they offer medical help. Deaths from overdoses dropped sharply. In 2017, Portugal had only 4 deaths per million people. The United States had 217 per million.

“In a society, you will have people who misbehave, says Hart. “But that doesn’t mean you should punish all of us because someone can’t handle this activity.”

He’s right. It’s time to end the drug war.

COPYRIGHT 2020 BY JFS PRODUCTIONS INC.

DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3ePvaWa

via IFTTT

About a month after Bill de Blasio personally led a police raid on a Hasidic rabbi’s funeral in Brooklyn, which he portrayed as an intolerable threat in the era of COVID-19, New York’s mayor visited the same borough to address a tightly packed crowd of protesters who had gathered in response to George Floyd’s death. Far from ordering them to disperse in the name of public health, the unmasked mayor enthusiastically expressed solidarity with the demonstrators.

The contrast between de Blasio’s anger at Jewish mourners and his solicitude toward political protesters figures prominently in last Friday’s decision by a federal judge who deemed New York’s pandemic-inspired restrictions on religious gatherings unconstitutional. The ruling, which said COVID-19 control measures violate the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious freedom when they draw arbitrary distinctions between religious and secular conduct, is a warning to politicians across the country as they loosen the sweeping restrictions they imposed in the name of flattening the curve.

“Something absolutely unacceptable happened in Williamsburg tonite,” de Blasio tweeted the day of the funeral raid. “When I heard, I went there myself to ensure the crowd was dispersed. And what I saw WILL NOT be tolerated so long as we are fighting the Coronavirus.”

De Blasio added: “My message to the Jewish community, and all communities, is this simple: the time for warnings has passed. I have instructed the NYPD to proceed immediately to summons or even arrest those who gather in large groups. This is about stopping this disease and saving lives. Period.”

But that period turned out to be a comma, followed by an exception for large outdoor gatherings promoting a cause that appealed to the mayor’s progressive instincts. As U.S. District Judge Gary Sharpe noted when he issued an injunction against New York’s limits on religious services, both de Blasio and Gov. Andrew Cuomo actively encouraged the recent protests against police brutality.

Sharpe agreed with the plaintiffs—two Roman Catholic priests from upstate New York and three Orthodox Jews from Brooklyn—that de Blasio and Cuomo had created a de facto distinction between religious and political gatherings. He also noted explicit restrictions on religious activities that did not apply to secular activities posing similar risks of virus transmission.

The rules limited attendance at indoor church and synagogue services to 25 percent of capacity while allowing various businesses, including stores, offices, salons, and restaurants, to operate at 50 percent of capacity and imposing no limit on special educational services. The state “specifically authorized outdoor, in-person graduation ceremonies of no more than 150 people” while imposing a 25-person limit on outdoor religious gatherings, including masses, funerals, and weddings.

The Supreme Court has said neutral, generally applicable laws that happen to restrict religious activities are consistent with the First Amendment. But it also has said laws that impose special burdens on religious activities are subject to strict scrutiny, meaning they are unconstitutional unless they are narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling government interest.

Sharpe concluded that New York’s rules were not generally applicable and could not pass the strict-scrutiny test. While that analysis seems straightforward, federal appeals courts have split on the question of whether state restrictions on religious services are neutral and generally applicable.

Last month, when the Supreme Court declined to issue an injunction against California’s restrictions, Chief Justice John Roberts dismissed the idea that the state was discriminating against houses of worship by applying special rules to them—a position that mystified the four dissenters. When churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples are prepared to follow the same social distancing and hygiene rules that apply to other settings where people gather for extended periods of time, they thought, there is no rational basis for treating them differently.

Courts are understandably reluctant to second-guess state and local decisions about how best to deal with a contagious and potentially deadly disease. But this is one of the areas where the Constitution requires a less deferential approach.

© Copyright 2020 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3ikdEeE

via IFTTT

Protesters say America’s criminal justice system is unfair.

It is.

Courts are so jammed that innocent people plead guilty to avoid waiting years for a trial. Lawyers help rich people get special treatment. A jail stay is just as likely to teach you crime as it is to help you get a new start. Overcrowded prisons cost a fortune and increase suffering for both prisoners and guards.

There’s one simple solution to most of these problems: End the war on drugs.

Our government has spent trillions of dollars trying to stop drug use.

It hasn’t worked. More people now use more drugs than before the “war” began.

What drug prohibition did do is exactly what alcohol prohibition did a hundred years ago: increase conflict between police and citizens.

“It pitted police against the communities that they serve,” says neuroscientist Carl Hart in my new video. Hart, former chair of Columbia University’s Psychology department, grew up in a tough Miami neighborhood where he watched crack cocaine wreck lives. When he started researching drugs, he assumed that research would confirm the damage drugs did.

But “one problem kept cropping up,” he says in his soon-to-be-released book, Drug Use For Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear, “the evidence did not support the hypothesis. No one else’s evidence did either.”

After 20 years of research, he concluded, “I was wrong.” Now, he says, our drug laws do more harm than drugs.

Because drug sales are illegal, profits from selling drugs are huge. Since sellers can’t rely on law enforcement to protect their property, they buy guns and form gangs.

Cigarettes harm people, too, but there are no violent cigarette gangs—no cigarette shootings—even though nicotine is more addictive than heroin, says our government. That’s because tobacco is legal. Likewise, there are no longer violent liquor gangs. They vanished when prohibition ended.

But what about the opioid epidemic? Lots of Americans die from overdoses!

Hart blames the drug war for that, too. Yes, opioids are legal, but their sale is tightly restricted.

“If drugs were over the counter, there would be fewer deaths?” I asked.

“Of course,” he responds. “People die from opioids because they get tainted opioids….That would go away if we didn’t have this war on drugs. Imagine if the only subject of any conversation about driving automobiles was fatal car crashes….So it is with the opioid epidemic.”

Drugs do harm many people, but in real life, replies Hart, “I know tons of people who do drugs; they are public officials, captains of industry, and they’re doing well. Drugs, including nicotine and heroin, make people feel better. That’s why they are used.”

President Eisenhower warned about the military-industrial complex. America’s drug war funds a prison-industrial complex. Hart says his years inside the well-funded research side of that complex showed him that any research not in support of the “tough-on-drugs” ideology is routinely dismissed to “keep outrage stoked” and funds coming in.

America locks up more than 2 million Americans. That’s a higher percentage of our citizens, disproportionately black citizens, than any other country in the world.

“In every country with a more permissive drug regime, all outcomes are better,” says Hart. Countries like Switzerland and Portugal, where drugs are decriminalized, “don’t have these problems that we have with drug overdoses.”

In 2001, Portugal decriminalized all drug use. Instead of punishing drug users, they offer medical help. Deaths from overdoses dropped sharply. In 2017, Portugal had only 4 deaths per million people. The United States had 217 per million.

“In a society, you will have people who misbehave, says Hart. “But that doesn’t mean you should punish all of us because someone can’t handle this activity.”

He’s right. It’s time to end the drug war.

COPYRIGHT 2020 BY JFS PRODUCTIONS INC.

DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3ePvaWa

via IFTTT

About a month after Bill de Blasio personally led a police raid on a Hasidic rabbi’s funeral in Brooklyn, which he portrayed as an intolerable threat in the era of COVID-19, New York’s mayor visited the same borough to address a tightly packed crowd of protesters who had gathered in response to George Floyd’s death. Far from ordering them to disperse in the name of public health, the unmasked mayor enthusiastically expressed solidarity with the demonstrators.

The contrast between de Blasio’s anger at Jewish mourners and his solicitude toward political protesters figures prominently in last Friday’s decision by a federal judge who deemed New York’s pandemic-inspired restrictions on religious gatherings unconstitutional. The ruling, which said COVID-19 control measures violate the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious freedom when they draw arbitrary distinctions between religious and secular conduct, is a warning to politicians across the country as they loosen the sweeping restrictions they imposed in the name of flattening the curve.

“Something absolutely unacceptable happened in Williamsburg tonite,” de Blasio tweeted the day of the funeral raid. “When I heard, I went there myself to ensure the crowd was dispersed. And what I saw WILL NOT be tolerated so long as we are fighting the Coronavirus.”

De Blasio added: “My message to the Jewish community, and all communities, is this simple: the time for warnings has passed. I have instructed the NYPD to proceed immediately to summons or even arrest those who gather in large groups. This is about stopping this disease and saving lives. Period.”

But that period turned out to be a comma, followed by an exception for large outdoor gatherings promoting a cause that appealed to the mayor’s progressive instincts. As U.S. District Judge Gary Sharpe noted when he issued an injunction against New York’s limits on religious services, both de Blasio and Gov. Andrew Cuomo actively encouraged the recent protests against police brutality.

Sharpe agreed with the plaintiffs—two Roman Catholic priests from upstate New York and three Orthodox Jews from Brooklyn—that de Blasio and Cuomo had created a de facto distinction between religious and political gatherings. He also noted explicit restrictions on religious activities that did not apply to secular activities posing similar risks of virus transmission.

The rules limited attendance at indoor church and synagogue services to 25 percent of capacity while allowing various businesses, including stores, offices, salons, and restaurants, to operate at 50 percent of capacity and imposing no limit on special educational services. The state “specifically authorized outdoor, in-person graduation ceremonies of no more than 150 people” while imposing a 25-person limit on outdoor religious gatherings, including masses, funerals, and weddings.

The Supreme Court has said neutral, generally applicable laws that happen to restrict religious activities are consistent with the First Amendment. But it also has said laws that impose special burdens on religious activities are subject to strict scrutiny, meaning they are unconstitutional unless they are narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling government interest.

Sharpe concluded that New York’s rules were not generally applicable and could not pass the strict-scrutiny test. While that analysis seems straightforward, federal appeals courts have split on the question of whether state restrictions on religious services are neutral and generally applicable.

Last month, when the Supreme Court declined to issue an injunction against California’s restrictions, Chief Justice John Roberts dismissed the idea that the state was discriminating against houses of worship by applying special rules to them—a position that mystified the four dissenters. When churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples are prepared to follow the same social distancing and hygiene rules that apply to other settings where people gather for extended periods of time, they thought, there is no rational basis for treating them differently.

Courts are understandably reluctant to second-guess state and local decisions about how best to deal with a contagious and potentially deadly disease. But this is one of the areas where the Constitution requires a less deferential approach.

© Copyright 2020 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3ikdEeE

via IFTTT

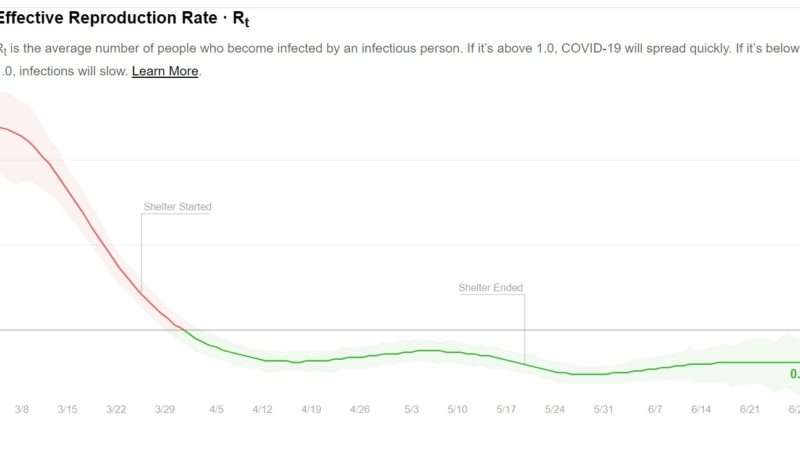

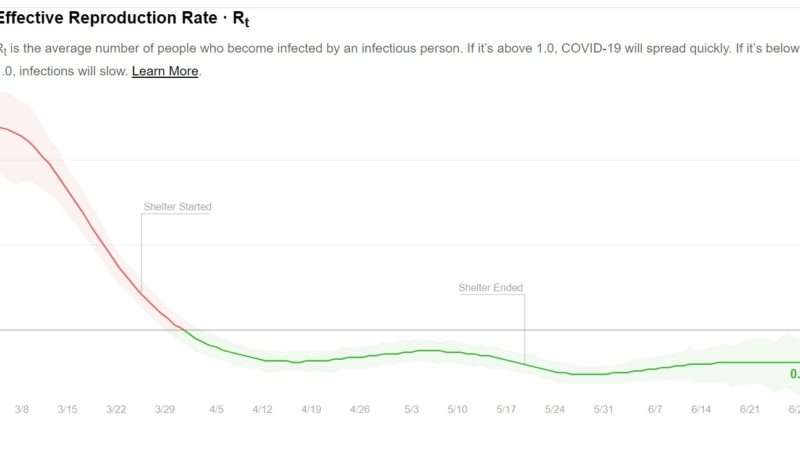

“By going into lockdown,” New York Times science writer Carl Zimmer matter-of-factly reports, “Massachusetts drove its reproductive number down from 2.2 at the beginning of March to 1 by the end of the month; it’s now at .74.” Zimmer is talking about the number of people the average carrier infects, and if the Massachusetts lockdown really did cut that number by two-thirds, it would be strong evidence that such policies are highly effective at reducing virus transmission. The truth, however, is rather more complicated.

Zimmer links to a chart that shows the reproductive number in Massachusetts falling precipitously in March. But that downward trend began more than three weeks before Gov. Charlie Baker issued his business closure and stay-at-home orders. By the time Massachusetts officially locked down on March 24, the number had fallen from 2.2 to 1.2. That decline continued during the lockdown, falling to a low of 0.8 by May 18, when the stay-at-home order expired and Baker began allowing businesses to reopen. It is therefore possible that closing “nonessential” businesses and telling people to stay home except for government-approved purposes reinforced the preexisting trend. But the lockdown had no obvious impact on the slope of the curve.

The reproductive number continued to fall sharply until the end of March, when it dropped below one, which indicates a waning epidemic. The drop then slowed, and the number fluctuated, going up and down a bit but always staying below one. Since the lockdown was lifted, the picture has stayed pretty much the same. The estimate for yesterday was 0.8, which is a bit surprising if you believe the lockdown was crucial in keeping the number low. Although it has been more than a month since Baker started reopening the state’s economy, virus transmission has not been notably affected. Newly confirmed cases, hospitalizations, and daily deaths are all trending downward.

If you are a fan of lockdowns, you can look at these numbers and conclude that the policy has been a smashing success in Massachusetts, as Zimmer seems to believe. But if you are at all skeptical of the marginal impact that lockdowns had at a time when Americans were already moving around less and striving to minimize social interactions (as shown by cellphone and foot traffic data as well as estimates of the reproductive number), you have to wonder how Baker’s orders reached back in time to affect behavior that happened before they took effect. Trends in other states pose a similar puzzle.

Even if we give Baker’s lockdown full credit for positive trends in Massachusetts after March 24, it clearly is not responsible for reducing the reproductive number by 45 percent before then, even though Zimmer implies otherwise. And since the subsequent drop of 33 percent was smaller, it is logically impossible even to give the lockdown most of the credit for reducing transmission.

If voluntary changes in behavior account for the decline in transmission before the lockdown, it seems reasonable to assume that they played an important role after March 24 as well. How important is the crux of the dispute between Americans who think lockdowns were absolutely necessary to curtail the epidemic and Americans who question that belief.

The rest of Zimmer’s article, which focuses on the outsized role that superspreaders have played in the pandemic, lends support to the latter camp. “Most infected people don’t pass on the coronavirus to someone else,” he observes. “But a small number pass it on to many others in so-called superspreading events.”

Research in Hong Kong, for example, found that “just 20 percent of cases, all of them involving social gatherings, accounted for an astonishing 80 percent of transmissions.” Another 10 percent of carriers “accounted for the remaining 20 percent of transmissions,” meaning that 70 percent of people infected by the virus did not pass it on to anyone. Because the reproductive number is an average, it obscures the significance of superspreaders, which is nevertheless important in weighing COVID-19 control policies.

One hypothesis about superspreaders, Zimmer notes, is that some people tend to harbor more of the virus than others, making them more likely to pass it on. But environmental factors are also important. When a lot of people are packed together in an indoor space with poor ventilation, any carriers who happen to be there are much more likely to transmit the virus, especially if they are singing, talking loudly, coughing, or sneezing.

“A busy bar, for example, is full of people talking loudly,” Zimmer writes “Any one of them could spew out viruses without ever coughing. And without good ventilation, the viruses can linger in the air for hours.”

What are the policy implications? “Knowing that Covid-19 is a superspreading pandemic could be a good thing,” Zimmer notes. “Since most transmission happens only in a small number of similar situations, it may be possible to come up with smart strategies to stop them from happening. It may be possible to avoid crippling, across-the-board lockdowns by targeting the superspreading events.” He quotes British epidemiologist Adam Kucharski: “By curbing the activities in quite a small proportion of our life, we could actually reduce most of the risk.”

In other words, even if Zimmer is right to assume that locking down Massachusetts drove down virus transmission, that does not mean similar results could not have been achieved through less costly, more carefully targeted policies. If “it may be possible to avoid crippling, across-the-board lockdowns by targeting the superspreading events,” that seems like an option that politicians should have considered before closing down the economy.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2CRrdC1

via IFTTT

“By going into lockdown,” New York Times science writer Carl Zimmer matter-of-factly reports, “Massachusetts drove its reproductive number down from 2.2 at the beginning of March to 1 by the end of the month; it’s now at .74.” Zimmer is talking about the number of people the average carrier infects, and if the Massachusetts lockdown really did cut that number by two-thirds, it would be strong evidence that such policies are highly effective at reducing virus transmission. The truth, however, is rather more complicated.

Zimmer links to a chart that shows the reproductive number in Massachusetts falling precipitously in March. But that downward trend began more than three weeks before Gov. Charlie Baker issued his business closure and stay-at-home orders. By the time Massachusetts officially locked down on March 24, the number had fallen from 2.2 to 1.2. That decline continued during the lockdown, falling to a low of 0.8 by May 18, when the stay-at-home order expired and Baker began allowing businesses to reopen. It is therefore possible that closing “nonessential” businesses and telling people to stay home except for government-approved purposes reinforced the preexisting trend. But the lockdown had no obvious impact on the slope of the curve.

The reproductive number continued to fall sharply until the end of March, when it dropped below one, which indicates a waning epidemic. The drop then slowed, and the number fluctuated, going up and down a bit but always staying below one. Since the lockdown was lifted, the picture has stayed pretty much the same. The estimate for yesterday was 0.8, which is a bit surprising if you believe the lockdown was crucial in keeping the number low. Although it has been more than a month since Baker started reopening the state’s economy, virus transmission has not been notably affected. Newly confirmed cases, hospitalizations, and daily deaths are all trending downward.

If you are a fan of lockdowns, you can look at these numbers and conclude that the policy has been a smashing success in Massachusetts, as Zimmer seems to believe. But if you are at all skeptical of the marginal impact that lockdowns had at a time when Americans were already moving around less and striving to minimize social interactions (as shown by cellphone and foot traffic data as well as estimates of the reproductive number), you have to wonder how Baker’s orders reached back in time to affect behavior that happened before they took effect. Trends in other states pose a similar puzzle.

Even if we give Baker’s lockdown full credit for positive trends in Massachusetts after March 24, it clearly is not responsible for reducing the reproductive number by 45 percent before then, even though Zimmer implies otherwise. And since the subsequent drop of 33 percent was smaller, it is logically impossible even to give the lockdown most of the credit for reducing transmission.

If voluntary changes in behavior account for the decline in transmission before the lockdown, it seems reasonable to assume that they played an important role after March 18 as well. How important is the crux of the dispute between Americans who think lockdowns were absolutely necessary to curtail the epidemic and Americans who question that belief.

The rest of Zimmer’s article, which focuses on the outsized role that superspreaders have played in the pandemic, lends support to the latter camp. “Most infected people don’t pass on the coronavirus to someone else,” he observes. “But a small number pass it on to many others in so-called superspreading events.”

Research in Hong Kong, for example, found that “just 20 percent of cases, all of them involving social gatherings, accounted for an astonishing 80 percent of transmissions.” Another 10 percent of carriers “accounted for the remaining 20 percent of transmissions,” meaning that 70 percent of people infected by the virus did not pass it on to anyone. Because the reproductive number is an average, it obscures the significance of superspreaders, which is nevertheless important in weighing COVID-19 control policies.

One hypothesis about superspreaders, Zimmer notes, is that some people tend to harbor more of the virus than others, making them more likely to pass it on. But environmental factors are also important. When a lot of people are packed together in an indoor space with poor ventilation, any carriers who happen to be there are much more likely to transmit the virus, especially if they are singing, talking loudly, coughing, or sneezing.

“A busy bar, for example, is full of people talking loudly,” Zimmer writes “Any one of them could spew out viruses without ever coughing. And without good ventilation, the viruses can linger in the air for hours.”

What are the policy implications? “Knowing that Covid-19 is a superspreading pandemic could be a good thing,” Zimmer notes. “Since most transmission happens only in a small number of similar situations, it may be possible to come up with smart strategies to stop them from happening. It may be possible to avoid crippling, across-the-board lockdowns by targeting the superspreading events.” He quotes British epidemiologist Adam Kucharski: “By curbing the activities in quite a small proportion of our life, we could actually reduce most of the risk.”

In other words, even if Zimmer is right to assume that locking down Massachusetts drove down virus transmission, that does not mean similar results could not have been achieved through less costly, more carefully targeted policies. If “it may be possible to avoid crippling, across-the-board lockdowns by targeting the superspreading events,” that seems like an option that politicians should have considered before closing down the economy.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2CRrdC1

via IFTTT

Two years ago, Justice Kennedy announced that he would retire from the Supreme Court. One of my earliest thoughts was, “I will never have to edit another Kennedy opinion for the casebook!” My follow-up thought was, “How long will I have to keep the Kennedy opinions in the casebook, once they are overruled or whittled away.” The whittling away has already begun. The Roberts Court is slowly, but surely interring Justice Kennedy’s ephemeral “jurisprudence of doubt.” Blue June has already buried at least three precedents with Justice Kennedy in the majority: Boumediene v. Bush, Whole Woman’s Health, and Footnote 3 of Trinity Lutheran.

Boumediene suffered two major blows during Blue June. The first hit came in DHS v. Thuraissigiam (see here and here). Justice Alito’s majority required a very precise fit between history and the Petitioner’s claim.

Despite pages of rhetoric, the dissent is unable to cite a single pre-1789 habeas case in which a court ordered relief that was anything like what respondent seeks here.

Justice Kennedy’s 2008 majority opinion relied on history in a very fluid fashion. In dissent, Justice Sotomayor wrote that Boumediene “never demanded the kind of precise factual match with pre-1789 case law that today’s Court demands.” She’s right.

As I read Thuraissigiam, the Court has closed the door to any future expansion of the Suspension Clause jurisprudence, unless there is a close analogue to historical practice in 1789. Indeed, Mike Dorf finds an even greater limitation:

In both St. Cyr and Boumediene v. Bush, the Supreme Court said that the Suspension Clause protects a right to habeas that is “at the absolute minimum” as expansive as the scope of habeas in 1789, leaving open the possibility of further expansion. Justice Alito’s opinion (1) finds that the scope in 1789 does not benefit Thuraissigiam and (2) does not go beyond that minimum.

The Court has now rejected any possible “evolving” notion of habeas. The Great Writ is solidified in amber.

Boumediene took another hit in a sleeper case of the term, Agency for Int’l Development v. Alliance for Open Society. Justice Kavanaugh’s nine-page decision resolved a really important constitutional question with very little fanfare. He wrote:

First, it is long settled as a matter of American constitutional law that foreign citizens outside U. S. territory do not possess rights under the U. S. Constitution. Plaintiffs do not dispute that fundamental principle. Tr. of Oral Arg. 58–59; see, e.g., Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U. S. 723, 770– 771 (2008); Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U. S. 507, 558–559 (2004) (Scalia, J., dissenting); United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez, 494 U. S. 259, 265–275 (1990); Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U. S. 763, 784 (1950); United States ex rel. Turner v. Williams, 194 U. S. 279, 292 (1904); U. S. Const., Preamble.

Justice Kavanaugh posed this precise question during oral argument:

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: Good morning, counsel. I want to clarify, first, one thing from your colloquy with Justice Ginsburg. You agree, I assume, that unaffiliated foreign entities acting abroad have no constitutional rights under this Court’s precedents.

MR. BOWKER: We do, Your Honor.

This concession was unwise. And I also think it was wrong.

Justice Breyer’s dissent explains the Court has never actually reached this sweeping conclusion.

Even taken on its own terms, the majority’s blanket assertion about the extraterritorial reach of our Constitution does not reflect the current state of the law. The idea that foreign citizens abroad never have constitutional rights is not a “bedrock” legal principle. At most, one might say that they are unlikely to enjoy very often extraterritorial protection under the Constitution. Or one might say that the matter is undecided. But this Court has studiously avoided establishing an absolute rule that forecloses that protection in all circumstances.

Breyer explains that Boumediene, which Kavanaugh cited, rejects such a categorical rule.

Nor do the cases that the majority cites support an absolute rule. See ante, at 3. The exhaustive review of our precedents that we conducted in Boumediene v. Bush (2008), pointed to the opposite conclusion. In Boumediene, we rejected the Government’s argument that our decision in Johnson v. Eisentrager, (1950),”adopted a formalistic” test “for determining the reach” of constitutional protection to foreign citizens on foreign soil. This is to say, we rejected the position that the majority propounds today. Its “constricted reading” of Eisentrager and our other precedents is not the law. See Boumediene, 553 U. S., at 764.

The law, we confirmed in Boumediene, is that constitutional “questions of extraterritoriality turn on objective factors and practical concerns” present in a given case, “not formalism” of the sort the majority invokes today.

Well, with AMK in the middle, Boumediene rejected “formalism.” But now “formalism” is the law with JGR in the middle. And five votes endorse Justice Jackson’s observation from Eisenstrager.

Boumediene is basically a dead letter. Never overruled, but currently interred.

Whole Woman’s Health was decided in June 2016, shortly after Justice Scalia passed away. The vote was 5-3. Justice Breyer’s majority opinion expanded upon the framework from Planned Parenthood v. Casey: courts should balance two factors: (1) whether the law imposed an “undue burden” on abortion access and (2) whether the law provides an actual benefits. Of course, Justice Kennedy assigned that majority opinion to Justice Breyer. And Kennedy no doubt realized that Breyer was departing from Casey. But 2016 was a bizarre year. Justice Kennedy also reversed his own opinion on affirmative action from Fisher I to Fisher II, that conflicted with his vote in the Michigan affirmative action cases. In any event, 2016 was so four years ago.

In June Medical, Chief Justice Roberts vote to uphold the Louisiana abortion law–and only the Louisiana abortion law. His concurrence casts serious doubt on Whole Woman’s Health. Indeed, he seems to suggest that WWH departed from Casey. Yesterday, I noted:

Going forward, there are five votes to limit the Court’s abortion framework to consider a a law’s burdens, without weighing the law’s benefits. The Chief has effectively overruled Whole Woman’s Health to the extent it departs from Casey. The Chief didn’t swing to the left; at most, he feinted left for this Blue June.

For reasons unknown, Roberts considers the Casey plurality (three votes) a valid precedent, but the WWH majority (five votes) is not a valid precedent. In any event, Justice Kennedy’s 2017 vote on abortion will be interred. But his 1992 vote on abortion is now, apparently, settled law. Go figure.

The vote in Trinity Lutheran was deceiving. On its face, the Court split by a 7-2 vote. But the majority was fractured. Justice Breyer only concurred in judgment. Chief Justice Roberts, and Justice Kennedy, Alito, and Kagan joined the majority opinion in full. And Justices Thomas and Gorusch joined the majority opinion, except for Footnote 3. Footnote 3 stated:

This case involves express discrimination based on religious identity with respect to playground resurfacing. We do not address religious uses of funding or other forms of discrimination.

In other words, Trinity Lutheran only concerned a case in which the state denies funding to the church because of its status as a house of worship. The case did not involve a denial of funding to the church because it would use money for “religious uses.” For example, instead of using funds to purchase tire scraps for the playground, the church could purchase funds to purchase books for religious instruction.

In a partial concurrence, Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justice Thomas, wrote that this distinction is flimsy.

First, the Court leaves open the possibility a useful distinction might be drawn between laws that discriminate on the basis of religious status and religious use. Respectfully, I harbor doubts about the stability of such a line.

In any event, the bulk of Trinity Lutheran was precedent, but Footnote 3 was not; it only garnered four votes. And could be disregarded just as quickly. Fast-forward to today, with Espinoza. Chief Justice Roberts wrote a majority opinion that was joined in full.

The Chief flagged the status/use distinction from Trinity Lutheran:

Some Members of the Court, moreover, have questioned whether there is a meaningful distinction between discrimination based on use or conduct and that based on status. See Trinity Lutheran, (GORSUCH, J., joined by THOMAS, J., concurring in part). We acknowledge the point but need not examine it here. It is enough in this case to conclude that strict scrutiny applies under Trinity Lutheran because Montana’s no-aid provision discriminates based on religious status.

Later, Roberts suggested that he was not tied to Footnote 3.

A plurality declined to address discrimination with respect to “religious uses of funding or other forms of discrimination.” Trinity Lutheran at n. 3. The plurality saw no need to consider such concerns because Missouri had expressly discriminated “based on religious identity,” which was enough to invalidate the state policy without addressing how government funds were used.

The key word is “plurality.” Not a majority. It seems that the Chief added Footnote 3 in Trinity Lutheran to assuage Justices Kagan and/or Kennedy. For the Chief, FN 3 was just another move in a game of 87-dimensional chess. He sacrificed a pawn to set up the Espinoza checkmate. Now, three years later, he no longer needs Justice Kennedy’s vote, and will not need to secure Justice Kagan’s on this case.

Trinity, and now Espinoza, also move away from the Rehnquist-Court era decision, Locke v. Davey. Michael Moreland observes that “Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote a narrow, almost case-specific holding (a characteristic Rehnquistian move)” in that case.

Justice Breyer seems miffed that the Court has abandoned the “play in the joints” line from Locke:

Although the majority refers in passing to the “play in the joints” between that which the Establishment Clause forbids and that which the Free Exercise Clause requires, its holding leaves that doctrine a shadow of its former self.

He’s right. There is no longer any need to appease Anthony Kennedy or Sandra Day O’Connor.

Going forward, I presumptively treat any 5-4 decision with Kennedy in the majority as persuasive, at best.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/31wsitf

via IFTTT