To prevent the spread of the coronavirus and cushion people from its economic impact, activists and politicians are pushing for moratoriums on evictions and foreclosures, and even for straight suspensions of rent payments.

The thinking is that forcing people to move out of their homes during a global pandemic—when we should all be practicing social distancing—will only make it easier for the virus to spread.

That’s an entirely reasonable concern. But we should also avoid any permanent expansion of government’s power to ignore property rights and private contracts.

Not that those long-term concerns are motivating government officials right now. Instead, they are emphasizing fast, immediate action.

“In this economic crisis, we need to place an immediate moratorium on evictions, foreclosures, and utility shut-offs,” tweeted Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) yesterday.

In this economic crisis, we need to place an immediate moratorium on evictions, foreclosures, and utility shut-offs.

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) March 12, 2020

“As we move through the COVID-19 emergency, people must be able to focus on our community’s health—slowing the virus’s spread—and not on economic survival,” said California state Sen. Scott Wiener (D–San Francisco) yesterday, in a statement similarly calling for a nationwide freeze on evictions (of commercial and residential tenants) and foreclosures.

The same day, 24 New York state senators sent a letter to New York State Court of Appeals Chief Judge Janet DiFiore, asking her to suspend all eviction proceedings.

“Many individuals and families who are evicted from their homes will be forced to live in public spaces, in shelters, or in other temporary and often precarious circumstances—limiting their ability to self-quarantine,” the senators wrote, citing as precedent past eviction moratoriums that’d been issued in the wake of 9/11 and Hurricane Sandy.

Signing onto the letter is democratic socialist Sen. Julia Salazar (D/WF–Brooklyn) who has been a major proponent of the public health benefits of an eviction freeze—while also yesterday sending out campaign volunteers to collect signatures for her reelection bid.

The real policy movement so far has been at the local level.

On Tuesday, the San Jose city council advanced a 30-day moratorium on evictions for those who can prove—via pay stubs, employer or doctor notes, etc.—that their health or income has been affected by the coronavirus. The moratorium is expected to be finalized within the next week or two, reports the Mercury News.

San Francisco Mayor London Breed has also committed to using her emergency powers to declare some form of eviction moratorium by the end of this week.

City councilmembers in Los Angeles plan to introduce some sort of moratorium legislation next week. The Los Angeles Times reports that it could apply to all renters in the city.

These are just a few examples. A CityLab article from Wednesday notes these efforts are being considered by cities across the country. Italy, one of the countries most affected by the spread of the coronavirus, has also suspended mortgage payments.

Individual landlords and their trade associations are giving these proposals mixed receptions, acknowledging the public health benefits while also complaining that they are being made to shoulder the entire cost of responding to the epidemic.

Daniel Yukelson, the executive director of Los Angeles’s Apartment Association, criticized that city’s proposed eviction moratorium to the Times, calling it “yet another horrible regulation that would unleash an undeserved and excessive amount of punishment on unsuspecting.” Yukelson said that eviction is a last resort, and landlords have been willing to make accommodations for good renters affected by the virus.

“Rents pay for property taxes, insurance, mortgages, maintenance, and the salaries of building supers and staff,” said the Community Housing Improvement Program (CHIP), an association representing smaller landlords in New York City, in a statement to Reason. “Missing an entire month of revenue would have a devastating effect on their ability to pay their expenses.”

CHIP has asked that any eviction moratorium be coupled with compensation to building owners to cover any financial losses.

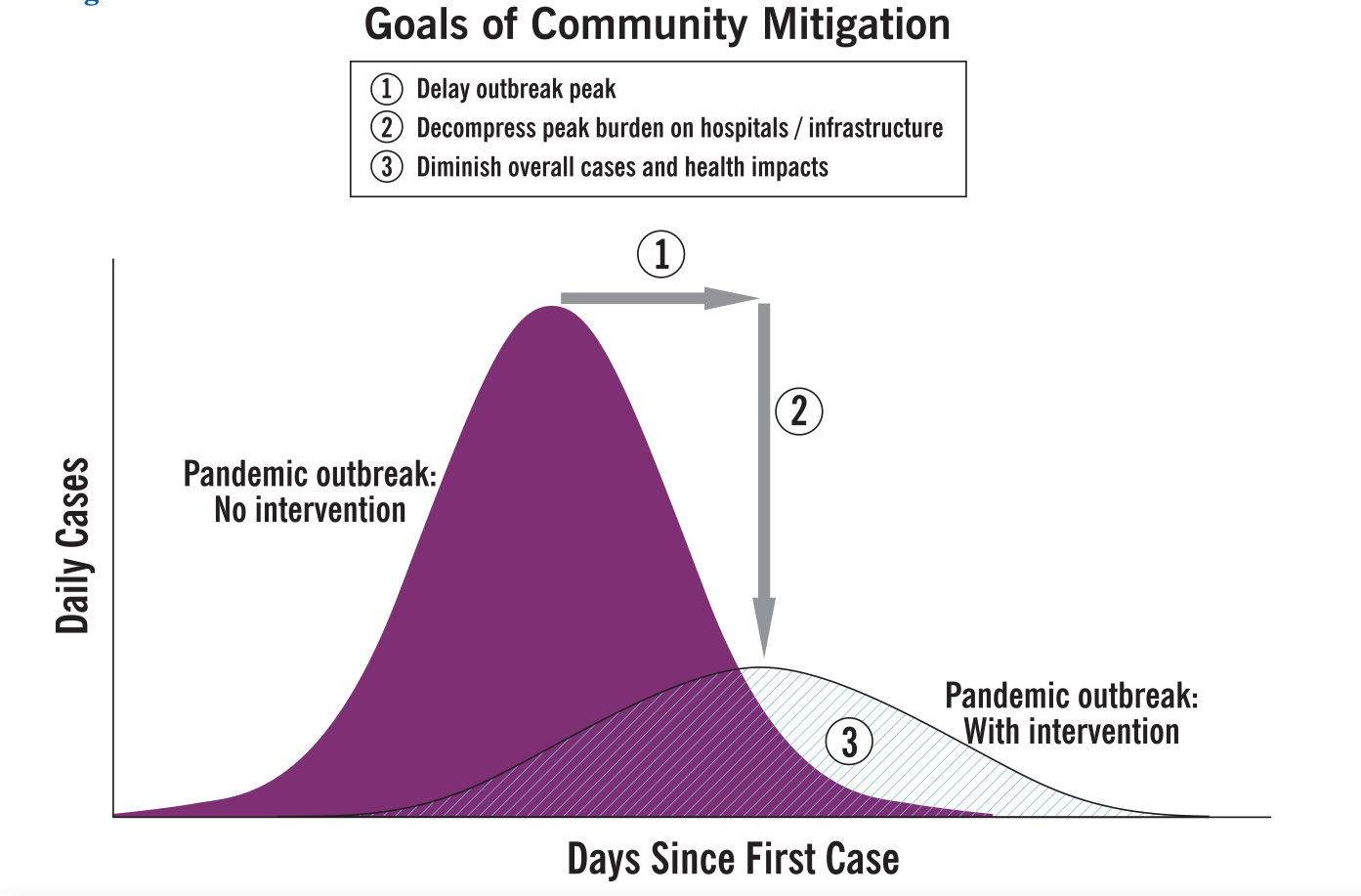

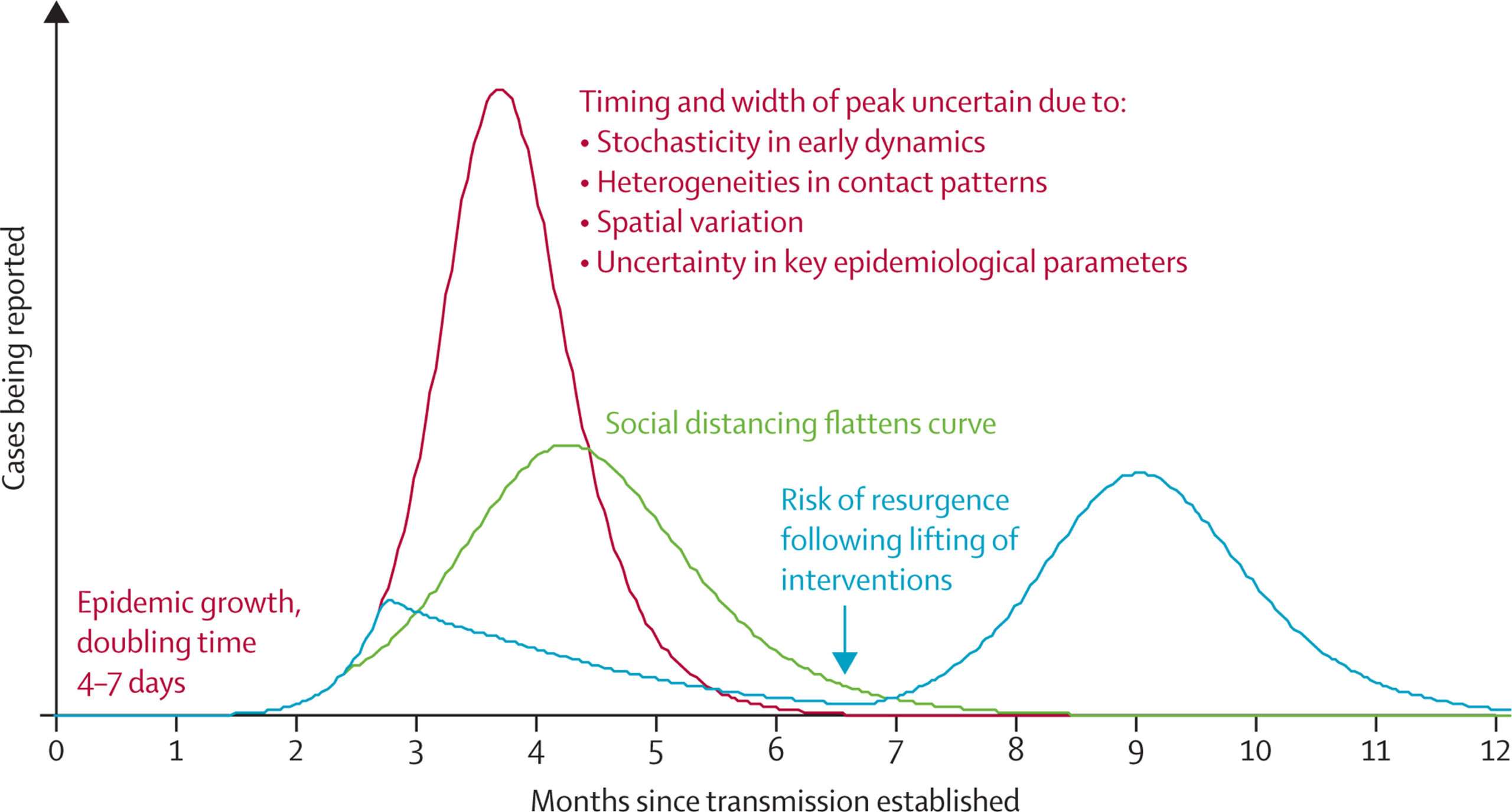

At a moment, the public health response is all about slowing the rate of infection through social distancing so that the number of new cases stays within hospitals’ capacity to treat them. Having fewer people being forced to move or show up to crowded courthouses to contest eviction notices would certainly help with that.

Yet landlords are correct in noting that government officials are effectively shifting the economic costs of the coronavirus from renters to them, often with only the vaguest promise of compensation. The fewer landlords that are able to make their mortgage payments because of lost rent only further imperils a financial system that has already proven shaky in response to the coronavirus.

As economist Pierre Lemieux noted on Twitter in response to Italy’s suspension of mortgage payments, that’s not a good thing for governments who will soon need additional funds to cope with the continued fallout from the pandemic.

Lenders are humans too and the virus, contrary to the state, does not discriminate on the basis of balance sheet. Moreover, bankrupt states may direly need more lenders soon. #discrimination #lenders #borrowers #coronavirus #Italy https://t.co/0WBbzIneNP via @CBSNews

— Pierre Lemieux (@pierre_lemieux) March 12, 2020

More worrisome still is the potential for a ratchet effect, whereby any suspension of evictions, while seemingly necessary or at least advisable at this moment, will lead to a permanent expansion of the government’s power to suspend rent or loan payments in the future.

In his book Crisis and Leviathan, economic historian Robert Higgs describes how major crises in the 20th century led to dramatic expansions in the scope of government power that persisted long after each individual crisis has passed.

During a crisis, argued Higgs, government officials are often unable or unwilling to transparently impose the full costs of their crisis-response measures onto the public. They, therefore, look to hide those costs behind coercive policies. Higgs writes:

“Modern democratic governments expand the scope of their effective authority over economic decision-making during crisis because citizens insist they ‘do something,’ and the alternative means of implementing the chosen policies, which is full reliance on pecuniary fiscal and market mechanisms, would reveal the costs of the government’s policies so clearly as to threaten the viability of both the policies and the ruling, somewhat autonomous governments themselves.”

In other words, governments unwilling to pay the market price for soldiers and steel during a war will adopt new powers to forcibly requisition men and materials instead.

This expansion of power, according to Higgs, doesn’t recede once a crisis is over. Rather, it leaves behind a legacy of more government power that can then be used in less extraordinary circumstances. Emergency powers become routine.

Something very similar could happen with eviction moratoriums.

There is no shortage of options governments have to help renters harmed by the coronavirus, and to do so transparently. Cities could give individual tenants subsidies to help pay their rent. They could also subsidize landlords, either through cash or tax breaks, who are losing out on rent because of the pandemic. They could even funnel money to banks to forestall foreclosures on rental properties.

These aren’t ideal free market policies, but in the current context of a global pandemic, they might be advisable public health measures.

Instead, governments are embracing a more drastic expansion of their power to freeze the enforcement of private legal contracts. To cut checks to affected parties would require either new revenue or service cuts, something few politicians want to consider in a time of looming recession.

The vague promises that landlords will be made whole by city governments are not encouraging. If that were true, there’d be no need for eviction moratoriums in the first place.

This is particularly concerning given that some of these moratoriums are being proposed for entire cities and states—and even the entire country—with no concern for whether someone has contracted the disease or lost income because of it.

If politicians are willing to do this now, in response to this current crisis, what would be the argument against returning to these policies the next time there is a (man-made) economic recession?

The immediacy of the coronavirus crisis is creating demands for immediate action. That’s understandable and, in a lot of cases, necessary.

So far, however, it’s been private actors and civil society that have responded best to the current pandemic. Private banks in Europe and the United Kingdom are already giving borrowers more time to pay their mortgages. Surely private actors here in the states can work out similar arrangements.

To rely on coercive government action leaves open the possibility for dangerous expansion of emergency regulatory powers that will be with us long after coronavirus is brought under control.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2QdsAyS

via IFTTT