After a half-century of existence, the Libertarian Party (L.P.) this morning wakes up to a situation it has never before experienced—with a sitting member of Congress proudly waving the Libertarian flag.

“I will be the first,” Rep. Justin Amash (L–Mich.) told me late Wednesday night, just after announcing his candidacy for the Libertarian presidential nomination. “And I’m happy to do that.”

Amash is not the only person smiling. In an email, Libertarian Party Chair Nicholas Sarwark said, “I’m happy to see that Representative Amash has come home to the political party most closely aligned with his views,” adding: “If more members of the House who are tired of being marginalized by the GOP and Democratic leadership joined him, we could see a caucus of legislators who are able to work for the American people instead of conflicting teams of special interests. My DMs are open.”

Amash, a persistent critic of President Donald Trump who left the Republican Party to became an independent last July 4, was facing a competitive reelection campaign in his 3rd District of Michigan, a state whose straight-ticket ballot option disfavors candidates outside the two major parties. Yet he says his seat could have been defended.

“That was one of the hardest parts of this decision,” he said. “When I’m looking at my polling, and fundraising, and other aspects with respect to the congressional campaign, I felt I was in the driver’s seat. I felt that I was in a very strong position to win it….But I just think this is too important.”

Amash, who is six-for-six in general elections (five in Congress, once in the Michigan House of Representatives), claims that the 2020 presidential contest is a “winnable race” for a Libertarian Party whose previous high-water mark, in 2016, was 3.3 percent of the vote.

“When I look at these candidates, I think most Americans see the same thing I’m seeing, which is these two candidates aren’t up to being president of the United States, and we need an alternative,” he said. The botched and expensive federal response to the COVID-19 outbreak only makes that clearer, he said. “Millions of Americans are seeing that the government spent trillions of dollars and still didn’t get it right. They didn’t get help to the people who need it most. Instead, most of the assistance went to people who have great connections, who run big corporations.”

I talked to Amash about his late entry into the Libertarian race, his policy objections to Joe Biden, his position on abortion, charges that he would “spoil” the effort to dethrone President Donald Trump, and more. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

—

Reason: What took you so long?

Amash: Well, I’ve been spending time with my family, with friends; I wanted to spend substantial time thinking about it carefully. And up until the past month or so, let’s say, I couldn’t really think about it that carefully. There were a lot of things going on in Congress, there were a lot of things going on in life.

Around February I decided I would pause my congressional campaign and really focus on the presidential race. And that meant at the time just researching things, seeing if it was a situation where I could come in as a candidate and win the race. And then over the past few weeks, I really sat down to dig into it and got to the point where I was confident that this was a winnable race. Because I don’t believe you should just run for fun or for messaging. I believe you should run to win, and to make an impact at the ballot box.

So I’m at that place, and I’m in.

Reason: So you start in mid-February—that’s not coronavirus o’clock, but the coronavirus came up by the beginning of March. So explain a little bit how that affected your deliberations, if at all.

Amash: Well, it certainly extended the deliberations. So if not for the COVID-19 situation, I would have been able to focus on it more carefully earlier. In other words, the really aggressive focus on the campaign—where I could think “Is it time to get in or not?”—had to be put on hold a little bit. I was already in the process of researching things, talking to people, talking to family and friends. But when the coronavirus came up, I had to slow that down, because that obviously affects the entire race, and obviously it affects my job, too. I’m in Congress trying to help constituents, making sure that they are getting the resources they need, and so it affected my ability to move forward quickly.

Reason: I look at the coronavirus thing in particular, and you see a lot of 388-5 votes in the House about various phases of this happening. Do you look at a situation in which $3 trillion has walked out of Congress in the last, I don’t know, six weeks—and basically overwhelmingly, near-unanimously, despite Thomas Massie’s best efforts. Is that a fruitful backdrop from which to run a limited-government campaign?

Amash: I think so. I mean, millions of Americans are seeing that the government spent trillions of dollars and still didn’t get it right. They didn’t get help to the people who need it most. Instead, most of the assistance went to people who have great connections, who run big corporations. Those people, they got it really fast; [Treasury Secretary Steven] Mnuchin couldn’t act fast enough to help those people.

But for millions of Americans who are unemployed or struggling right now, they couldn’t get relief to those people, because they have a massive convoluted system, and they doubled and tripled down on it. They said, “Hey, how can we take our bad system and make it worse? Let’s add a whole bunch of restrictions, let’s add a whole bunch of qualifications, let’s try to get money to small businesses, but then make it so that the money is not all that useful to them. Let’s put banks in the middle of it to slow down the process.”

And the banks are trying; they’re trying, I’m not blaming the banks. I blame Congress and the administration for creating such a system….The Los Angeles Lakers applied for relief as a small business, and you know, under the terms of the deal that Congress put together with the White House, that’s actually allowed. But they never thought through this thing, really.

Reason: So you said that you had to think about this in terms of “Can I win? Can I compete meaningfully?” (But you said “win.”) Explain how that calculation works; explain the path. Because I look at the same thing, and in times of high polarization and high partisan interest, you oftentimes see a kind of Death Valley for third parties and independents trying to run for everything. So how do you look at this thing and see a win?

Amash: I look at the candidates running and I see two candidates that are not qualified for the office. Yeah, they have long resumes, different resumes. The president as a reality [TV] star, and as a sometimes successful, sometimes failed businessman; and Joe Biden as a longtime member of Congress who’s on his third run for president, and frankly, doesn’t seem to be up to it.

So when I look at these candidates, I think most Americans see the same thing I’m seeing, which is: These two candidates aren’t up to being president of the United States, and we need an alternative. And I’m confident that I can be that alternative.

What people are really looking for is practicality. They see these two sides in Washington, Red and Blue, fighting with each other every day. When it comes to most pieces of legislation, they’re highly polarized. And then when it comes to the really bad stuff that gets passed, all of a sudden they become best friends. So they’re fighting each other day and night on stuff that often doesn’t impact people directly, and then when you get something that really hurts the American people, they get unified all of a sudden.

This is not the system the American people want. It’s not the system the framers designed. And we need to trust the people. We need to have humility regarding the process of government. And that means allowing legislators to legislate, and keeping the executive branch in check, and having a court that does its job interpreting and deciding cases. We can’t have this system where these two parties just run amok and hurt Americans every day.

Reason: Are you getting out of the race for reelection in Congress, or are you waiting to see what happens at the Libertarian National Convention?

Amash: My campaign is paused, but frankly, I’m running this campaign for president, and I don’t intend to return to my congressional campaign.

It’s been an honor to represent the 3rd District, and that was one of the hardest parts of this decision. When I’m looking at my polling, and fundraising, and other aspects with respect to the congressional campaign, I felt I was in the driver’s seat. I felt that I was in a very strong position to win it. And as I’ve gone around the district, I’ve had tremendous support from constituents everywhere I go, and from all across the political spectrum. So that was a very tough decision to say that I’m going to run for another office. But I just think this is too important.

And I do think we need someone who’s going to govern with some humility, and I don’t just mean personal humility. I think when people hear the word humility, they think of a person who is kind, or gracious, or whatever. That’s not the kind of humility I’m talking about. I’m talking about humility with respect to the process. Humility with respect to how much one individual knows about things.

What you really have right now are two presidential candidates who think they know everything, and want to run everything. And you see the mess that’s happening right now just with the coronavirus relief, where you get this one person thinking they know everything, instead of using the type of knowledge that exists out among the public, which is the knowledge of time and circumstances, things that only people on the ground know, that no one in Washington can know, or no one in the state Capitol can know.

Reason: Members of the Libertarian Party who like you, and have preferred you, and in fact have wanted you to run for a long time, have expressed some irritation of, “Jesus, Hamlet, get off the fence! We’ve been out here trying to build a party, and go to state conventions, and engage in debates, and this is a little bit late in the game.” What do you say to those people as you try to win a majority of a thousand delegates?

Amash: Well, I want to earn their support. I respect the process, I respect the delegates. If it were up to me, and everything had run smoothly, I would have made a decision earlier. But life comes up, things come up. The COVID-19 situation came up, for example, and there are other things that have come up over the past year. And I don’t control all those things.

But I took the time I needed to make a decision. I feel confident about the decision, and I want to go and earn the support of the Libertarian Party. And I don’t think that any person running simply deserves the support. I think they have to go earn it. And I’ll spend a lot of time over the next several weeks speaking to Libertarians, speaking to delegates, and trying to win their support.

Reason: Do you plan on, or have you thought about seeking a vice-presidential copacetic kind of nominee? As you well know, the nominating process is kind of peculiar to the Libertarian Party in this sense, but other candidates such as Jim Gray have reached out to Larry Sharpe, for example. Do you have an approach like that?

Amash: I haven’t reached out to any V.P. candidates or potential candidates to ask them to come on as part of any ticket or anything like that. I want to take the time to talk to people, and I want to be respectful of the process; I want to be respectful of the delegates. I believe that the delegates should have a real say in who the V.P. is on the ticket.

The only thing I ask is if I’m the nominee, I think it’s important that the V.P. be someone who shares a lot of my philosophy, understands the messaging, and can go out there and earn the respect of the entire public. Because running a race for president is not just about one party or one ideology. We have to win lots of people. And we can stay true to our principles while doing that, but it’s important that we expand our reach, and so I think it’s important to have a vice president who understands that.

Reason: Your positions, as I know them, and the Libertarian Party’s platform, as I know it, have a lot of overlap; they’re pretty congruent in many ways. A strong exception to that would be abortion. Can you explain your position on that, as it intersects with federal government policy? What are your preferences on what the federal government should do, or what a Supreme Court should do, having to do with abortion?

Amash: Well, I’m pro-life, and I believe the 14th Amendment provides a strong federal basis for protecting life. But I think the most important thing the federal government can do is not fund abortion. And I think that there is probably broad support for that in the Libertarian Party, to ensure that the federal government is not funding abortions because the federal government shouldn’t be funding something that is that controversial to millions of Americans.

Reason: You had, on either Twitter or on your Amash for America rollout, an emphasis on seeking to represent all Americans. It almost felt italicized in that sense—all Americans. Why that particular emphasis? What does that mean to you?

Amash: It means that there are a lot of people right now who don’t feel represented. When you go around just to my district, for example, and talk to people, they don’t feel that the Republican Party or the Democratic Party really cares about them. And it’s not surprising why they feel that way.

When you look at what the two parties talk about in Washington, they’re hyper-focused on relatively small constituencies, but the ones who are politically active, and get them to win at the ballot box. There’s a large group of Americans that have been forgotten, and we need to reach out to those people, and we need to be the party that represents people from all backgrounds, that brings people together.

And there’s a strong message for bringing people together, which is that the purpose of government is to secure our rights. It shouldn’t matter what your background is; you want your rights secured. Many people right now feel that the government has forgotten them, and doesn’t care about its purpose, and is focused on minutiae, or the politics of the moment, and has forgotten totally about the essential purpose of government, which is to secure the rights of the people.

Reason: Take a swing at Joe Biden in terms of policy. You’ve talked previously that he doesn’t seem like he’s got it all there, which I think we can observe. What’s wrong with him as someone who executes policy, who’s been in public life for a half-century?

Amash: Well, first, he’s held just about every position, which is something that Trump does week to week, but Joe Biden has also held multiple positions over his lifetime. It’s okay to change your mind about things—I’ve changed my mind on things, everyone has changed their mind on things. But when you do it over and over again about multiple big issues, you start to question whether the person’s changing their mind, or whether they’re just doing it for political expediency.

A few examples might [include] the Iraq War. He’s got some wild explanation for why he voted for the authorization but didn’t really support the war. He was one of the architects of a lot of the surveillance that we have today. Back in the day, he was heavily pushing programs that evolved into things like the PATRIOT Act, and FISA [the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act], and he’s been wrong on criminal justice reform time and again. So it’s nice to see that he’s changed his mind on some of these things, or says he’s changed his mind. But at this point, it’s time to pass the baton to a new generation and have other people taking the lead on these issues.

And there are other issues where I don’t think he’s changed his mind. Look at this coronavirus relief [approach]. You hear about him saying, “Oh, well maybe this isn’t how I would have done it,” but he’s still applauding [House Speaker] Nancy Pelosi and [Senate Majority Leader] Mitch McConnell and President Trump, essentially, as they passed this kind of thing that doesn’t directly help the people; it’s another corporate welfare scheme in many respects.

So he hasn’t been good on those issues, and I don’t think he’ll be good on those issues going forward. When you look at some of the potential V.P. candidates he’s thinking about, you’ll probably get the same kind of thing—someone who isn’t very good on civil liberties issues, and hasn’t been good on other issues that progressives and many libertarians and many moderates across the political spectrum care about.

Reason: I don’t know why you gotta be so mean to Kamala Harris there.

Amash: I think you know who I was talking about.

Reason: There are quite a few people who agree with you about Trump, or agree with your critiques of Trump over the past year, over the past three years, who are saying, “Jesus Christ, man, not now! Why would you do this? You are jeopardizing—there’s been one poll in Michigan done with you in it and with you out of it, and you knock six points off Biden’s lead—why would you get in the way of removing someone who is uniquely unfit for office?” How do you respond to those people?

Amash: Well, first I would say with respect to the polling, that a poll taken a year ago when you don’t even have the Democratic deal decided, and where I still have very low name ID, doesn’t really mean that much. So I wouldn’t put too much stock into it. Especially when you’re taking a poll around the time that impeachment and other things were going on, and maybe some people on the left thought I was going to be on their side on every issue under the sun because I was in favor of impeachment. And that’s just not correct.

I think the greater likelihood is that I draw from a lot of dissatisfied Republicans, but even if you set aside the two parties, Republicans or Democrats, there are millions and millions of independent and libertarian-minded voters who either are forced to vote for one of these two if they don’t have other choices on the ballot, or who aren’t going to vote at all if they’re required to choose between those two candidates.

And I believe there are enough votes out there to win this race. I wouldn’t be running if there weren’t enough votes to win this race. So people can talk about the “spoiler” thing—I think it’s all academic; it’s hard to say which pot of voters you pull from. But I don’t think it matters that much; I don’t think you’d ever figure it out. And in any case, there are millions of people who want an alternative, and that’s important. We shouldn’t deny them an alternative, deny them a chance to vote for someone who will be practical and have common sense. Why should we force them to vote for one of these other two candidates?

Reason: All right, final question. Are you going to be a Libertarian in Congress?

Amash: I am, yes.

Reason: You are. So you’re going to be the first Libertarian member of Congress.

Amash: I expect so, yeah. I don’t think there’s been another Libertarian in Congress, so I will be the first, and I’m happy to do that.

I do think that the Libertarian Party is important. I spent the past almost year, not quite a year, as an independent…and I’ve learned a lot about the process, a lot about the system. I think most people agree that we’d like to get to a place in this country where political parties don’t matter, but we’re not there yet. That is more of a long-term project. I think we can get there. I don’t think it’s in the distant, distant future, but I think it is still in the distant future. So one distant, but not two distants, in distances.

But right now, these two parties need a strong competitor. And the Libertarian Party has that opportunity because there are so many Republicans who are disenchanted with what’s going on with the Republican Party. There are so many Democrats who are disenchanted with what’s going on with the Democratic Party. And then on top of that, there are millions of Americans who aren’t closely affiliated to the parties, who want to have the opportunity to vote for an alternative. And over the last couple cycles, you’ve seen the Libertarian Party votes pick up, and I want to help it go further. I want to help the Libertarian Party win.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/35enfxH

via IFTTT

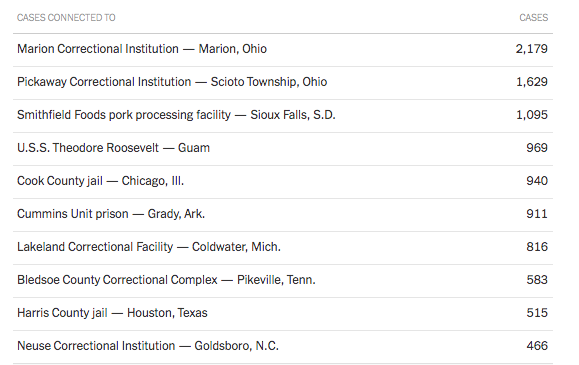

Other clusters include Lakeland Correctional Facility in Michigan, where more than 600 inmates have tested positive; the Cook County Jail in Illinois, which is nearing 1,000 positive cases; and Pickaway Correctional Institution in Ohio—the second-largest COVID-19 cluster in the country with 1,629 cases.

Other clusters include Lakeland Correctional Facility in Michigan, where more than 600 inmates have tested positive; the Cook County Jail in Illinois, which is nearing 1,000 positive cases; and Pickaway Correctional Institution in Ohio—the second-largest COVID-19 cluster in the country with 1,629 cases.