Liberalism in America is at a record high, according to new study. The country’s “public policy mood,” a “measure of left/right preferences over policy choices in American politics,” was more liberal in 2018 than at any previous point in the history of recording it.

“The annual estimate for 2018 is the most liberal ever recorded in the 68 year history of Mood, just slightly higher than the previous high point of 1961,” wrote James Stimson, a political scientist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, while sharing his latest findings.

The liberalism mood score for 2018 was about 69.15, according to the data file Stimson shared. In 1961, it was 68.92.

Stimson suggests that the 2018 estimate “represents the expected leftward movement in thermostatic reaction to the Presidency of Donald Trump,” but “should not be taken…as only a personal reaction to Trump because its defining items are the issues of American politics of earlier generations, the New Deal and Great Society agenda. And the estimates do not include Trump’s signature issues of immigration restriction and trade protectionism.”

That last bit is crucial. There are many ways to talk and think about liberalism. A lot of proverbial ink is spilled these days on whether “liberal democracy” or sometimes just “liberalism” is declining globally in the face of various political movements. But those big-picture concerns evoke liberalism in the classical sense (respect for individual rights, political autonomy, free markets, etc.). Meanwhile, “liberalism” as bandied about by mainstream politicians may mean any number of things.

In this study, liberalism and conservatism are measured by levels of support for various government programs. The survey covers a wide swath of policy areas, framed in broad terms. (You can read more about them in a 2012 paper from Stimson, available online with free registration here.)

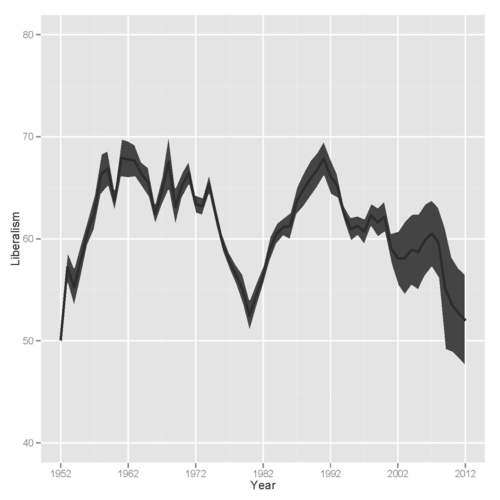

Stimson developed the Policy Mood measure in 1991, and it’s become a respected indicator used in a lot of people’s research. (Find more of his work here.) Here’s a graph Stimson did a few years of the data up to 2012:

“From 1992 to 2012, according to Stimson’s analysis, overall support for liberal, pro-government initiatives has declined,” noted Thomas B. Edsall in The New York Times back in 2013. Half a decade later, the picture looks rather different.

Liberalism’s low points on the Mood scale came in 1952 (49.88), 1980 (51.21), 1981 (53.19), 1982 (53.329), and 1969 (53.33).

The only time the liberalism measure slipped under 60 this century was in 2001 (59.39) and 2014 (59.51)

FREE MINDS

Medical marijuana doesn’t endanger workers. In fact, workplace fatalities are down in states with legalized medicinal weed:

In Medical marijuana laws and workplace fatalities in the United States, researchers D. Mark Anderson, Daniel I. Rees, and Erdal Tekin analyzed data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia between 1992 and 2015.

The goal: to determine the association between MMLs and workplace fatalities.

The researchers used Bureau of Labor Statistics data on workplace fatalities by state and year. Regression models were adjusted for state demographics, the unemployment rate, state fixed effects, and year fixed effects.

Their conclusion: legalizing medical marijuana has actually improved workplace safety—at least for workers aged 25–44.

Workplace fatalities were down in medical marijuana states by 19.5 percent on average.

FREE MARKETS

Seattle dancers are fed up with booze ban at strip clubs. Katie Herzog takes a look at how Washington state’s liquor laws are hurting workers at Seattle-area strip clubs. Local workers “say that Seattle is one of the most difficult and least lucrative cities to be a stripper, in no small part thanks to the statewide ban on alcohol sales,” Herzog writes.

In other cities and states, strip clubs make the bulk of their money from the sale of booze. In Seattle, clubs make their money off the dancers themselves, who have to pay for the privilege of working. And those house fees are not cheap: At Deja Vu, a local chain with a near-monopoly in the downtown area, dancers are charged $120 to $180 a night—and if they don’t make that money, the club will charge them back rent.

The lack of alcohol also changes the vibe. “Tourists and bachelor parties might come in, but when they realize they can’t get a drink, they leave,” Aubrey said. Unlike in, say, Portland—where strip clubs are allowed to serve booze and food, and where female customers and co-ed groups aren’t an uncommon sight—Seattle strip clubs tend to attract mostly men on their own.

At least some on left and right are pushing back hard against tech moral panic. David French and Glenn Greenwald both offered some some wise words yesterday on social media deplatforming and demonetizing controversies. Here’s French at National Review:

The regularity of the controversies—combined with the persistence of the overt viewpoint discrimination—is resulting in a demand that government “do something” to solve the problem. But the problem is far too complex and deep-seated for the government to solve. And if the government tries to step in with too heavy a hand, it’s going to violate the law. It’s past time for an honest, realistic look at the true cultural, commercial, and constitutional challenges to social-media fairness.

And here’s Greenwald, who spoke about the subject on the Tucker Carlson show last night:

Since the Media Matters & Vox hall monitors whose job is to take pictures of the TV and post distorted out-of-context clips did that to me tonight, here are my full comments on whether Silicon Valley overlords will benevolently police our discourse to protect the marginalized: pic.twitter.com/0oOoYUc5VW

— Glenn Greenwald (@ggreenwald) June 7, 2019

QUICK HITS

- After Donald Trump threatened new tariffs on Mexican goods coming to the U.S., officials from both countries are reportedly “discussing the outlines of a deal that would dramatically increase Mexico’s immigration enforcement efforts and give the United States far more latitude to deport Central Americans seeking asylum,” according to The Washington Post. But their sources “cautioned that the accord is not final and that President Trump might not accept it.”

- Adventures in doublethink: “Freedom of speech isn’t the same thing as the freedom to broadcast that speech,” insists April Glaser in an all-around misguided Slate piece calling for internet companies to be regulated more like broadcast networks.

- J.D. Tuccille explores the status of FBI’s new facial recognition database.

- The woke surveillance state welcomes you to Manchester’s Gay Village. “Look fabulous, you’re on CCTV!”

No, I’m not making this up. I wish I were. pic.twitter.com/DpfNu9vmka

— Helen Dale (@_HelenDale) June 6, 2019

- The latest jobs numbers are out and unemployment remains at 3.6 percent.

- In Connecticut,”‘raising women up’ apparently means depriving them of employment opportunities.” Reason‘s Scott Shackford looks at the latest expansion of occupational licensing rules for salon staff.

- Writer Molly Jong-Fast on Reason Editor-at-Large Nick Gillespie: “I’m horrified by some of the stuff he writes, but I am a good friend of his.”

- Unionizing efforts at Vox aren’t going so well.

from Latest – Reason.com http://bit.ly/2Wu1kRJ

via IFTTT