Adam Lowther was a busy man, traveling constantly for his work as director of the Air Force’s Advanced Nuclear Deterrence Studies. But on the afternoon of August 30, 2017, he called his wife, Jessica, with good news: He would be home in time to take their two children—ages 4 and 7—to tae kwon do practice.

Little did Adam know that he was about to be forcibly separated from his children for half a year, and would spend more than $300,000 in legal bills trying to reunite his family after it was torn apart by the New Mexico Children, Youth, and Families Department (CYFD) on the basis of a false sexual abuse accusation. Now Adam and his wife are suing the police and child services officials for violating their rights, misleading other authorities about the merits of the case against them, and traumatizing their children.

They are suing, not just in hopes that they might recover some of their financial losses, but also to bring about institutional change. The experience has opened up the Lowthers’ eyes to the inequities of the criminal justice system—and they don’t want anyone to go through what they did.

“We never thought this kind of thing could ever happen,” Adam told Reason. “We assumed that law enforcement was competent and we assumed that they obeyed the law. That was a wrong assumption, but that was our assumption.”

In the middle of that August 30 phone call with her husband, Jessica heard a knock at the front door of their Albuquerque home. It was the police. They told her they had come to perform a welfare check on the kids.

“I’m sorry, a welfare check?” asked Jessica, according to a court transcript of the encounter. “I don’t understand.”

Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Deputies Catherine Smalls and Brian Thornton explained that someone from one of the kids’ schools had called the authorities to report abuse. Jessica was baffled. She asked the officers if they were sure they had the right house. They were sure. She asked them to wait outside until Adam arrived at home. They agreed, but ordered Jessica not to shut the front door.

“I’m telling you, we take this stuff very seriously,” said Smalls.

As if to illustrate this point, Thornton told Jessica that “if this was my investigation, you would be in the back of a cop car right now. You’re obstructing our duty to check on the well-being of a child.”

But it was not yet the county sheriff’s investigation—it was CYFD’s investigation. An agent from the department would be interviewing Becca, the Lowther’s 4-year-old daughter, about abuse that she had allegedly reported to a teacher at school, according to the cops.

“I assume we’re not going to tae kwon do tonight?” asked Jessica.

“I… yeah,” said Smalls. “Pretty much assume that.”

***

Adam grew up in Houston, Texas. He was an Eagle Scout and enlisted in the military when he turned 18. Later, he attended Arizona State University (ASU), eventually earning a Ph.D. in International Relations. In 2008, he joined the Air Force Research Institute. In 2015, he became director of the Air Force’s Advanced Nuclear Deterrence Studies, a position that required top secret security clearance. He is also the author of several books on national security topics.

Jessica and Adam met at ASU through an organization for Conservative Baptist students. “We’ve been together since 1997,” Adam says. “Married over 20 years.”

The Lowthers eventually settled in Albuquerque. In their third year there, as summer 2015 drew to a close, daughter Becca was a few days shy of her fifth birthday, and thus could not enroll in the local public school her brother attended. Instead, Adam and Jessica sent her to a private school, Calvary Christian Academy.

In the middle of her second week at the school, her kindergarten teacher, a woman named Betty DuBoise, called the authorities to report that Becca had claimed her father and brother sexually assaulted her. (Throughout this article, I refer to the two children using the pseudonyms “Becca” and “Charlie.”) The Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Office (BCSO) showed up at the Lowther residence within the hour. They told Jessica that Becca had been “very descriptive” about what had happened, but did not specify the exact nature of the complaint. When Jessica pressed them for more information, they rebuffed her, and said they would not give further details until after a therapist had interviewed Becca. Jessica asked if this therapist was on their way over to the house. No, the officers revealed. Becca would be taken to the therapist.

“You’re going to take her away?” Jessica asked.

It was at this point that Smalls and Thornton decided there was “no reasoning” with Jessica, and asked her to step aside or be detained. Given no other choice, she let the officers inside to check on the kids. Jessica tried to explain to Becca what was going on, but Smalls stopped her because “that could be seen as coaching her.”

Outside, Adam had been arrested when he arrived on site and placed in the back of a cop car. He told the officers that they couldn’t enter his home without a warrant, but they said they didn’t need one, citing a New Mexico statute that authorizes the police to take children into protective custody if the authorities have a reasonable belief that the kids are in danger.

Of course, the police also made clear that they always assume the kids are in danger, if that’s what was reported.

“When we investigate things like this, whether it’s an anonymous call or [whatever], we have to take these cases involving children at their word and at their absolute worst,” the officers told the Lowthers.

In this case, the officers chose to rely heavily on the word of Becca’s teacher, Betty DuBoise, who had known the child for eight days. What DuBoise had told the cops, the Lowthers would later learn, was that she had overheard Becca ask another student if he had a penis—a word the Lowthers claim she did not and could not have known. DuBoise then pulled Becca aside and questioned her: It was at this point, according to the teacher, that Becca claimed her father had touched her inappropriately and penetrated her with his finger. Her brother also touched her, DuBoise claimed.

In her short time as Becca’s teacher, DuBoise had questioned the Lowthers about their daughter’s habit of sticking her hand down her pants, according to Adam. They promised to talk to Becca about this, but saw it as normal behavior for a child her age, and evidently did not show the matter as much seriousness as DuBoise expected.

More than a year later, Deputy District Attorney Leila Hood of the Albuquerque Special Victims Unit would issue a letter to Bernalillo County investigators detailing her numerous reasons for declining to prosecute Adam—issues with DuBoise’s statements chief among them. But the night of his arrest, the authorities simply presumed everything they had been told must be true.

“They made no effort to verify anything that the teacher had said,” says Adam.

The police kept him in the backseat of a hot car for hours before finally taking him to the station around 10:30 p.m. Since Adam was under arrest and Jessica was “detained,” the children were technically without guardians, and the state took them into protective custody. Adam would not see them again until March.

***

Within three days, the media had gotten a hold of the story. The Albuquerque Journal ran with the headline, “Nuke Expert at Kirkland Accused of Raping 4-Year-Old Girl.” Adam’s mugshot accompanied the article.

He was released after a week in jail, but couldn’t return home. He also lost his job and security clearance.

“Adverse publicity created by the local news media coverage concerning your charges and allegations has had an adverse effect upon the Department of the Air Force,” wrote Adam’s boss, a general. “Your alleged off-duty criminal misconduct and subsequent publicity cannot be tolerated in your position which requires utmost trust and integrity during the development of Nuclear Deterrence Studies.”

Meanwhile, for the Lowther’s 7-year-old son, Charlie, protective custody was anything but. After all, he too stood accused of sexual abuse. The police took both children to All Faiths, a private organization that acts as a safehouse for local law enforcement. Detectives interviewed Becca for over an hour. They also interviewed Charlie for 45 minutes about abuse he may have either suffered or perpetrated. Note that at this point, Charlie was in state custody—the very authorities legally responsible for his well-being were also interrogating him about whether he should be considered a suspect in a criminal investigation.

Becca was also forced to undergo not one but two separate sexual abuse examinations. To say that these were incredibly intrusive would be an understatement: Nurses examined, and even photographed, her anus.

“My daughter was forced through several invasive exams of her private parts,” says Adam. “She is petrified of doctors to this day.”

The children were then sent to foster care for 48 hours. Afterward, CYFD allowed Jessica to get them back, but only under the supervision of her own parents, who were required to move into the Lowther residence and serve as “safety monitors.”

But a few days later, CYFD again took custody of the children. At a September 5 hearing, Jessica’s father had told a social worker that he did not believe Adam was guilty. The social worker promptly reported this to Maria Morales, who was the investigator for CYFD, and Jacob Wootton, the detective assigned to Adam’s criminal case. Morales swore an affidavit alleging that Jessica was an unfit mother. Jessica lost custody again, this time for two full months. Becca and Charlie were separated—not just from their parents, but also each other.

***

It was a rough time for the family. Adam had to live with an elderly couple he knew from church. The children were in foster care. Charlie had a particularly difficult time, and met with his school counselor on 55 separate occasions—even threatening to kill himself. Jessica was home alone with the family dog, who passed away in late October.

Finally, on November 7, the children’s court judge decided to return custody to Jessica. Wootton was furious, and confronted the judge in his quarters, where he fumed that returning custody to Jessica would ruin his criminal case against Adam. The exchange was overheard by Adam’s attorney, Marc Lowery.

“I could hear a commotion coming from the judge’s chambers,” says Lowery. “I heard loud voices and when I looked in I saw the detective talking with the judge. They were arguing about the case.”

The judge was unmoved by Wootton’s ranting, and restored Jessica’s custody anyway. Wootton’s next move was to arrest Jessica. He did so the second she set foot outside the courthouse.

“This was malicious,” says Adam. “I’m not sure what lengths there were to which [Wootton] would not go to get what he wanted.”

In a criminal complaint filed against Jessica on the afternoon of September 7, Wootton claimed that Becca had told DuBoise—who was still her teacher, as mandated by CYFD—that during one of the supervised visits between mother and daughter, “mommy whispers in my ear not to say anything, to be quiet.” DuBoise made this report on October 19, three weeks before Wootton arrested Jessica for it. The charge against her was “bribery or intimidation of a witness.”

The cops took Jessica to jail, strip-searched her, and forced her to take a pregnancy test before releasing her on personal recognizance. Thankfully, the district attorney decided not to press charges, and Jessica finally got the kids back.

Adam’s reunion took longer—much longer. Months later, in March 2018, the court allowed Adam to have supervised visits with his children. The criminal case against Adam had by then collapsed: Though the detectives had repeatedly threatened to go to a grand jury, they never did so, and thus actual criminal charges never materialized. In April, the court-mandated therapist opined that Adam was not a threat to the kids, and his custody was restored the next month. On May 31, the Lowthers sold their home and moved to Texas, understandably eager to put as many miles between them and the Albuquerque authorities as possible.

***

On September 14, 2018, the Lowthers filed a lawsuit alleging that BCSO, CYFD, Wootton, Morales, and three other specific agents of law enforcement had violated the family’s rights and harmed the children.

The suit raised important questions about whether child services was acting in the children’s interests, or in service of a dubious criminal investigation.

“Immediately after the removal and late into the night, the children were subjected to hours of forensic interviews,” the Lowthers write in the suit. “The forensic interviews and physical examinations were conducted without a warrant or court oversight. CYFD, who was the guardian of the children, acted with indifference to the trauma caused by the forensic interviews and examinations. Indeed, the removal decision was made in furtherance of the criminal investigation—not to keep the children safe from harm. This itself was contrary to the children’s interests and violative of their constitutional rights.”

The lawsuit also made the noteworthy claim that DuBoise had “a history of legal troubles, including convictions for shoplifting and several lawsuits for failure to pay bad debts, which bears on her credibility.” A copy of a private investigator’s report confirming these allegations was obtained by Reason.

When reached for comment, Calvary Christian Academy’s principal declined to answer any questions about DuBoise. According to Adam, she no longer works for the school, and her own attorney has had trouble getting in touch with her.

BCSO did not respond to a request for comment. A spokesperson for CYFD declined to comment, citing pending litigation.

The Albuquerque Journal, which had previously published Adam’s mugshot under the “Nuke Expert Accused of Raping 4-Year-Old Girl” headline, covered the lawsuit more even-handedly in a subsequent article, “Lawsuit Says Sexual Assault Charge Is Groundless.” This may have prompted District Attorney Raul Torrez to review the case, and on October 18, his deputy—Leila Hood, of the special victims unit—wrote a letter detailing the myriad reasons why the office declined to prosecute Adam. The letter was addressed to Jacob Wootton.

In Hood’s opinion, Becca’s statements to investigators during her safehouse interview conflicted with what she had allegedly told DuBoise. Hood quoted one of the doctors who had interviewed Becca: “She does not know the difference between truth and lie. She likely does not understand the concept of a deliberate lie, she feels no compunction to tell the truth because she is not cognitively developed enough to comprehend the difference.” Hood also noted that investigators had fed Becca false information, calling the entire enterprise into question. In the district attorney’s opinion, her father having benignly assisted her with toilet-related issues was a plausible explanation for whatever story she may or may not have told DuBoise.

Hood also had an issue with DuBoise’s credibility, or at the very least her blind faith in Becca’s stories. In the middle of Wootton’s effort to stop Jessica from regaining custody, DuBoise had signed an affidavit that Becca had claimed her father was attending church with her, in violation of a court order. But this was impossible: Adam was wearing an ankle monitor, and Becca was under the supervision of a social worker while at church.

A polygraph examination administered by the Bernalillo Sheriff’s Department also lent credence to Adam. The department had initially interpreted the test to mean that Adam’s answers were “deceptive,” but the district attorney conducted an independent analysis: Bernalillo had misunderstood the results, which were “favorable to the alleged perpetrator,” according to Hood.

In filing their lawsuit, the Lowthers hope to recoup some of the estimated $300,000 they lost defending themselves. They also hope to discourage the authorities from handling child abuse cases in such a manner.

“I can only imagine how bad it is for other families,” said Adam. “We want this to stop.”

Indeed, while the Lowthers were financially well equipped to handle legal troubles of this nature, they still ended up having to borrow money. Other families who routinely deal with child services and law enforcement are often in even more precarious positions. Diane Redleaf, an attorney who represents families in child services disputes, told Reason‘s Lenore Skenazy that most of her clients are impoverished, and many are immigrants or racial minorities. Half of all black kids in the U.S. will receive a visit from child services, according to one study by the American Journal of Public Health. The state’s coercive power to separate children from their parents is most often experienced by those with scant ability to fight back.

This is something that resonates with the Lowthers. Adam and Jessica are conservatives, but their experience with the criminal justice system significantly altered their thinking.

“Prior to this, I would never have called myself a supporter of Black Lives Matter,” said Adam. “My view of law enforcement has completely changed.”

from Latest – Reason.com http://bit.ly/2IIqZyM

via IFTTT

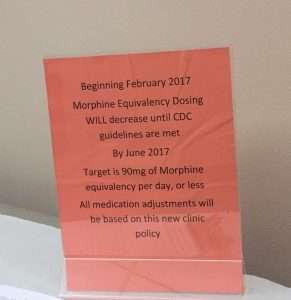

Notwithstanding Dowell et al.’s disavowal of “hard limits and abrupt tapering,” that is what

Notwithstanding Dowell et al.’s disavowal of “hard limits and abrupt tapering,” that is what