Pessimistic technology reporter Kevin Roose has a piece in Tuesday’s New York Times with the disconcerting yet accurately representative headline, “How the Biden Administration Can Help Solve Our Reality Crisis.” Pegged to the twin anxieties over right-wing conspiracy theories and violence, Roose’s article contains one of the most blink-inducing paragraphs I have ever encountered in a respected journal:

Several experts I spoke with recommended that the Biden administration put together a cross-agency task force to tackle disinformation and domestic extremism, which would be led by something like a “reality czar.”

Cue scores of snorting noises on Twitter about our new “Ministry of Truth.”

“It sounds a little dystopian, I’ll grant,” Roose concedes. “But let’s hear them out.”

OK, let’s. Harvard’s Joan Donovan, research director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, joins the recent political-class chorus calling for a “truth commission,” and pushes for the feds to have access to Facebook/Twitter/YouTube algorithms: “We must open the hood on social media so that civil rights lawyers and real watchdog organizations can investigate human rights abuses enabled or amplified by technology.”

Stanford Internet Observatory disinformation researcher Renée DiResta advocates a centralized counter-conspiracy task force, because if federal agencies are doing that work separately, “you run the risk of missing connections, both in terms of the content and in terms of the tactics that are used to execute on the campaigns.” Various pols and pundits propose rewriting Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act while using anti-trust threats to tame Big Tech; counter-extremism specialist Micah Clark plumps for a “social stimulus,” and hate-group deprogrammer Christian Picciolini opts for the kitchen-sink approach: “We have to destroy the institutional systemic racism that creates this environment. We have to provide jobs. We have to have access to mental health care and education.”

These thought bubbles may sound like unintentional self-parody to libertarian ears, but they are common both among the people who just re-took power in Washington and the knowledge workers who are glad they did. “We’re going to have to figure out how we reign in our media environment so that you can’t just spew disinformation and misinformation,” Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D–N.Y.) warned on Jan. 13. A day earlier, Politifact founder Bill Adair and Duke professor Philip Napoli argued that Biden “should announce a bipartisan commission to investigate the problem of misinformation and make recommendations about how to address it. The commission should take a broad approach and consider all possible solutions: incentives, voluntary industry reforms, education, regulations, and new laws.”

So merely as a matter of prevent defense, it’s worth taking these ideas both seriously and literally. Starting with a point so obvious that only journalists and academics could miss it: Proposed changes to government policy should always be visualized with the opposing team in charge of implementation. Imagine as the annointer of a Reality Czar not Joe Biden, but President Ted Cruz, or President Tucker Carlson. You people do remember that the White House was the scene of insane meetings like this all of two weeks ago, right?

There are also several structural problems with tasking government to encourage and adjudicate society’s net store of capital-T Truth. Politicians (such as Joe Biden and Kamala Harris) are incentivized to embellish their credentials, fictionalize their biographies, and misrepresent their records. Government agencies, given their druthers, would rather operate like the CIA—funding essentially guaranteed, details not available on request. As our resident Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) filer C.J. Ciaramella frequently reminds us, it’s the norm for bureaucrats to “flout the spirit and, quite often, the letter of federal record law.” And the last time Joe Biden was in the White House, his boss left “a blueprint on how to suppress information and get away with it.”

Truth is but one of many interests grasping for the steering wheel on the ship of state, and its lobbyists are comparatively underpaid. Realpolitik, interest-group payouts, and paternalistic efforts to shape citizen behavior all warp the common use of language and fact.

There’s a reason why U.S. officials can’t gin up the courage to call the century-old Turkish genocide of more than 1 million Armenians a “genocide,” yet are currently characterizing China’s brutal, though non-mass-murderous, suppression of its Uighur minority with a G-word even while several human rights groups do not (see also: “states that sponsor terrorism“). The Food Pyramid and its antecedents have been many things, but revealed truth is not one of them. The Centers for Disease Control, name-checked in Roose’s article, changed its recommendations on masks based more on behavioral effects than science. War is a perpetual lie-making machine, and that includes the War on Drugs.

The messy reality of overlapping bureaucracies and their conflicting interests may be one reason why pundit imagineers are tempted by “centralization” and the notion of a “czar.” It’s the eternal lure of a single magic wand. And about as childish.

“The knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use,” F.A. Hayek famously observed, “never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess.” The more you centralize the processing and dissemination of knowledge, the greater the range and effect of potential error.

The centralization of U.S. intelligence under a single Department of Homeland Security after 9/11 was supposed to make us smarter and faster, and yet its single most visible impact on our lives is invasive and ineffective security screening at airports. California Gov. Gavin Newsom has throughout the COVID-19 pandemic kept “key virus data out of public sight,” the Associated Press reported Jan. 22, lest the little people get confused. In related news, Newsom kept outdoor playgrounds in sunny California closed for several months after a preponderance of studies had demonstrated that kids were not spreading it to one another outdoors. Science is a dispersed, contested, and constantly evolving process, not an on-off switch best entrusted to a single enlightened source.

I will let my colleagues Elizabeth Nolan Brown and Andrea O’Sullivan (twice), respectively, argue against gutting Section 230, using anti-trust against Big Tech, and giving the government access to social media algorithms, though props to Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis for demonstrating the dangers this week. But a final word about some kind of “truth commission.”

Here’s yet another political-class endorsement of that idea, from Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Will Bunch last month:

Congress needs to create a Truth and Reconciliation process — a commission, perhaps, or even just an open forum — that will allow some or hopefully most to acknowledge Biden’s victory, state for there record that there was no election fraud in 2020, and maybe even apologize for saying otherwise.

Last year — before we had any idea the 45th president would incite an insurrection against the U.S. government — some of us called for a national Truth and Reconciliation Commission to address the lies and the anti-democratic policies of the Trump years. For that idea, we were vilified by some right-wingers who acted as if we were proposing a Nuremberg-war-crimes-trial kind of operation. But in fact a Truth and Reconciliation Commission — as successfully pulled off in South Africa and other strife-riven countries — is a chance for finding a common national story, for amnesty and a new beginning.

I’d be shocked if this happened, but I don’t know any other peaceful path forward.

Hyperbole aside, can you spot the flaw in this oft-used historical analogy? South Africa was a brutal racist police state. Most countries that have staged variants on truth commissions or qualified amnesties for past collaborators did so in large part because they were transitioning from authoritarianism to liberal democracy, and doing so requires immediate creative thinking about how to deal with past crimes and operate a current government without re-filling the prisons. It’s a damnably hard problem, not least because laws change dramatically in such transitions, prompting difficult questions about how to assign culpability to actions and collaborations that were perfectly legal in the Before Times.

Regardless of how darkly you characterize the Trump administration, that analogy just does not apply to the United States. Our laws, with almost no exception, are the same, and are in fact being used to prosecute hundreds of people connected with the Jan. 6 Capitol Hill ransacking. There are no pressing questions of lustration, of property-denationalizing, of teaching old civil service new codes of behavior.

Shorn of such urgencies, any proposed Truth Commission process looks more like a one-sided lecture, potentially backstopped by some government coercion aimed at those who are producing and consuming media in ways that the commissioners find distasteful. Not a very promising scenario for “reconciliation.”

Readers who’ve made it this far may be under the impression that I am blasé about the mainstream hold that conspiratorial twaddle has placed on ostensibly governing Republicans. In fact, I am not—there’s a mutually reinforcing rot in conservative politics and media, one whose main culprits are the politicians, journalists, and consumers who are either doing media literacy wrong, or making the cynical decision to pander to fantasies they themselves don’t believe in. It’s not a pretty picture, and blaming the left-leaning media is no excuse for any of it.

But what should said media do? Here is where my view diverges sharply. Journalists and media-theoreticians right now think the solution to Trumpy delusion is to deplatform even sitting U.S. senators, sic the feds on Fox News, break up Big Tech, reject “bothsidesism,” use the most maximally negative adjectives to describe Republicans, and reposition journalism as a tool for producing better democratic outcomes through applied moral clarity.

I think those approaches will backfire. Deliberately shrinking the public square is no way to persuade consumers on the edges of the debate. Injecting more moralizing into fact-gathering is unlikely to make the end product more factual. Giving the government more power over the rules and practice of free speech is, well, dystopian.

My recommendation to journalists and their cousins in government and academia will be neither popular nor satisfying, but here it is: Do your own jobs better. That’s it, that’s the memo. If government was efficient and helpful, if journalism was compelling and truthful, if the academe was relevant and unpredictable, their lectures would have far more resonance, and audience.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2Lg6YCF

via IFTTT

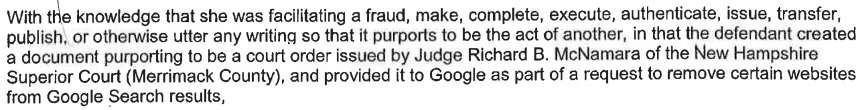

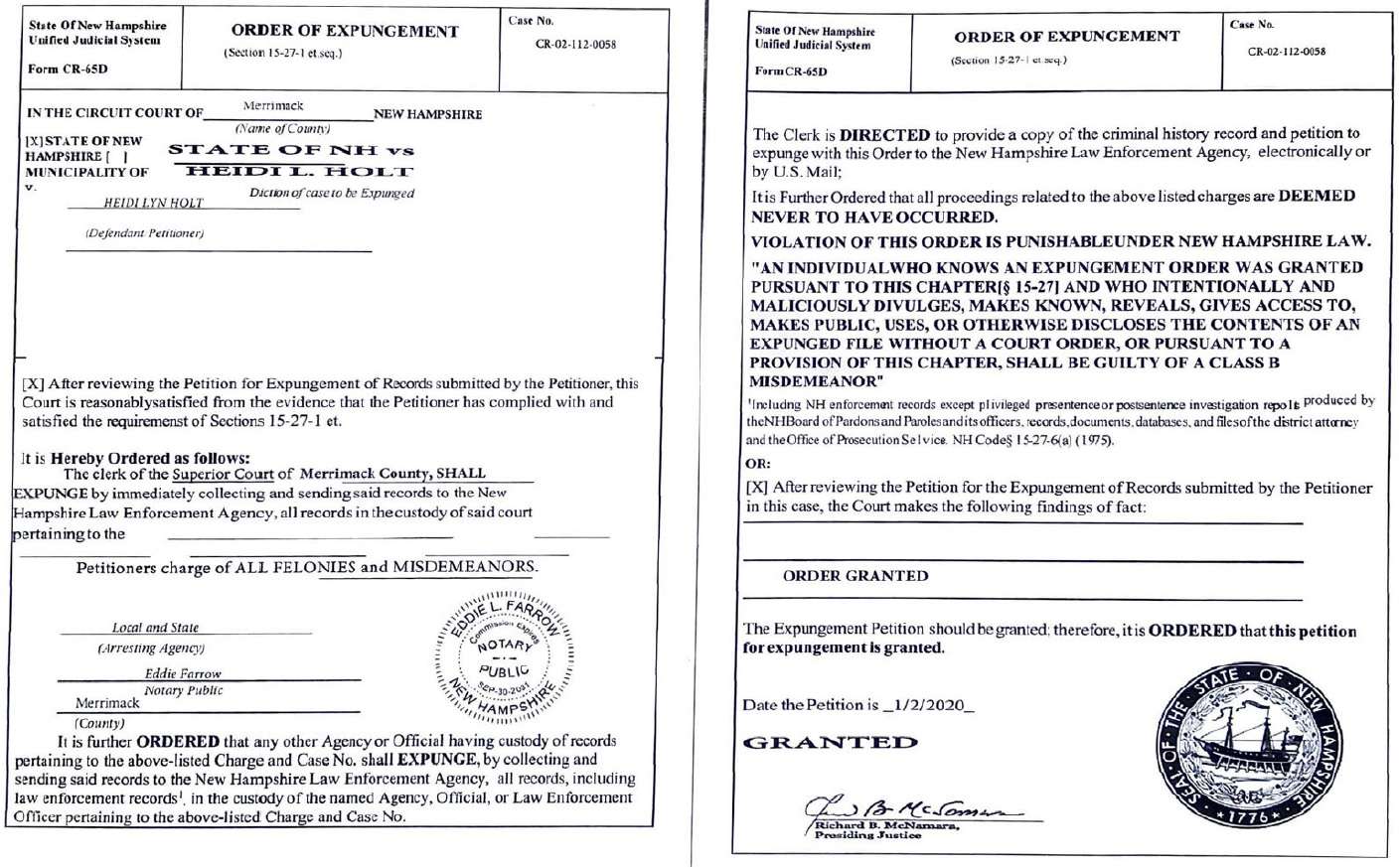

The alleged forgery was submitted to Google with a deindexing request for these pages:

The alleged forgery was submitted to Google with a deindexing request for these pages: