2/18/1988: Justice Anthony Kennedy takes judicial oath.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/38zhQlw

via IFTTT

another site

2/18/1988: Justice Anthony Kennedy takes judicial oath.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/38zhQlw

via IFTTT

Nedra Miller said she let officials at Florida’s River Ridge High School know weeks earlier that her son would not be at school one day because of an appointment with an orthodontist. Her son, William, made the mistake of dropping a friend off at school that day. And when William tried to leave, a Pasco County Sheriff’s Office deputy and Cindy Bond, a school discipline assistant, tried to block him as he drove away. The confrontation was caught on the deputy’s body camera. “You’re gonna get shot you come another f—ing foot closer to me,” the deputy said as the boy tried to drive around them. “You run into me, you’ll get f—ing shot.” William wasn’t shot, but he was suspended and later expelled from school. The sheriff’s office is refusing to identify the deputy, saying they can’t release his name while the incident is under investigation. It did confirm he’s still working at the school.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/37GfdNn

via IFTTT

Presidents’ Day should be a day of reflection on the virtues of the leaders who helped to preserve, protect, and defend our constitutional republic. So let’s look at the record of George Washington and the armed citizenry.

In early 1775, tensions between Great Britain and the American colonies were reaching the breaking point. The previous October, King George III had forbidden the import of arms and ammunition into the colonies, a decision which the Americans interpreted as a plan to disarm and enslave them. Kopel, How the British Gun Control Program Precipitated the American Revolution, 38 Charleston Law Review 283 (2012).

Without formal legal authorization, even from the Continental Congress, Americans began to form independent militias, outside the traditional chain of command of the royal governors. In February 1775, George Washington and George Mason organized the Fairfax Independent Militia Company.

According to Mason’s Fairfax County Militia Plan for Embodying the People, “a well regulated Militia, composed of the Gentlemen, Freeholders, and other Freemen”

was needed to defend “our ancient Laws & Liberty” from the Redcoats. “And we

do each of us, for ourselves respectively, promise and engage to keep a good Fire-lock in proper Order, & to furnish Ourselves as soon as possible with, & always keep by us, one Pound of Gunpowder, four Pounds of Lead, one Dozen Gun Flints, & a pair of Bullet-Moulds, with a Cartouch [cartridge] Box, or powder-horn, and Bag for Balls.” 1 The Papers of George Mason 210-11, 215-16 (Robert A. Rutland ed., 1970). Similar militias were being formed all over the American colonies, with no formal authorization and no chain of command to the established government. The legal bases of the militias were the natural rights of self-defense and self-government.

Because Virginia’s House of Burgesses had been suspended by the Royal Governor, Lord Dunmore, the defiant Virginians assembled in Richmond in March 1775 as a special convention. There, delegate Patrick Henry gave his famous speech, “The War Inevitable.” William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (1817). As Henry accurately explained, all petitions for peaceful conciliation with the British had been “spurned with contempt.” The British army in North America had only one purpose: “to force us to submission.” Because war was inevitable, Henry argued, it was better to fight now, before the British could take Americans’ guns:

An appeal to arms and to the God of hosts is all that is left us! They tell us, sir, that we are weak; unable to cope with so formidable an adversary. But when shall we be stronger? Will it be the next week, or the next year? Will it be when we are totally disarmed, and when a British guard shall be stationed in every house?…Sir, we are not weak if we make a proper use of those means which the God of nature hath placed in our power. Three millions of people, armed in the holy cause of liberty, and in such a country as that which we possess, are invincible by any force which our enemy can send against us.

Indeed, a few weeks later, on the evening of April 18, the British army occupying Boston would march off to Lexington and Concord to conduct house-to-house searches to seize firearms and gunpowder. The American resistance to arms seizures would mark the beginning of the American Revolution.

Persuaded by Henry’s eloquence, the Virginia Convention formed a committee—including Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson—”to prepare a plan for the embodying, arming, and disciplining such a number of men as may be sufficient” to defend the commonwealth. The Convention urged “that every Man be provided with a good Rifle” and “that every Horseman be provided . . . with Pistols and Holsters, a Carbine, or other Firelock.” (“Firelock” was a synonym for “flintlock,” the most common firearms of the time.) Journal of Proceedings of Convention Held at Richmond 10-11 (1775).When the Virginia militiamen assembled a few weeks later, many wore canvas hunting shirts adorned with the motto from the conclusion of Henry’s speech: “Liberty or Death.” Henry Mayer, A Son of Thunder: Patrick Henry and the American Revolution 251 (1991).

As Major General and Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the War of Independence, Washington had to deal with soldiers who were adamant about their personal independence. Even Americans who enlisted in the Continental Army often refused to sign up for more than a year. At the end of their year, they might leave for home, in the middle of a campaign. George Washington’s surprise attack on the British at the Battle of Trenton, Dec. 26, 1776, was a risky, successful gamble to win a victory before the imminent expiration of enlistments left him without a functioning army. The previous winter, the American expedition to take Canada had been forced to launch a premature, unsuccessful attack on Quebec City because half the American enlistments would expire in January.

The militias posed even more problems. For one thing, they were reluctant to be sent on distant deployments, so Washington did not always have the manpower he needed for a given batttle. On the other hand, by fighting part time and working on their farms the rest of the time, American citizen-soldiers kept the economy afloat.

The sedentary nature of the militia created, surprisingly, a superiority in tactical mobility. British naval dominance (before the French arrived later in the war) meant the British army could always move faster than the Continental Army and could attack anywhere near the coast. But the militia, comprised of most able-bodied adult males, could rise wherever the British deployed. As historian Daniel Boorstin put it, “[t]he American center was everywhere and nowhere—in each man himself.” Daniel

Boorstin, The Americans: The Colonial Experience 370 (1965).

The Americans could better afford losses in battle because a large fraction of the adult population was available to fight. Redcoats or German mercenaries imported from across the Atlantic were more difficult to replace. The British could capture cities on or near the coast—such as Boston, New York City, or Savannah. Yet control of the vast interior proved impossible. Many militiamen had learned warfare from Indian fighting. In the mountains, swamps, and forests, they denied use of the country to the British. The militiamen had the advantages of intimate knowledge of the terrain, support from much of the local population, and the ardor that comes with defending one’s homeland.

Whether in the militia or the Continental Army, the guns deployed were mostly personal firearms. As late as 1781, George Washington insisted that enlistees in the Continental Army provide their own guns. Letter from George Washington to Joseph Reed (June 24, 1781), in 22 The Writings of George Washington 258 (Jared Sparks ed., 1834); Letter from George Washington to Thomas Parr (July 28, 1781), in id. at 427.

Americans’ experience with firearms helped make them effective fighters. In 1789, historian David Ramsay recounted the June 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill: “None of the provincials in this engagement were riflemen, but they were all good marksmen. The whole of their previous military knowledge had been derived from hunting, and the ordinary amusements of sportsmen. The dexterity which by long habit they had acquired in hitting beasts, birds, and marks, was fatally applied to the destruction of British officers.” 1 A History of the American Revolution 190 (Lester H. Cohen ed., Liberty Fund, 1990) (1789).

As Washington wrote in 1777, “Our Scouts, and the Enemy’s Foraging Parties, have frequent skirmishes; in which they always sustain the greatest loss in killed and Wounded, owing to our Superior skill in Fire arms.” Letter from George Washington to John A. Washington (Feb. 24, 1777), in 7 Writings of George Washington, at 198.

Washington worried, however, that although militiamen were good shots, they were troublesome to employ in a long campaign, for the militia’s “want of discipline & refusal, of almost every kind of restraint & Government, have produced . . . an entire disregard of that order and subordination necessary to the well doing of an Army.” Letter from George Washington to John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress (Sept. 2, 1776), in 5 Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, at 733 (Worthington Chauncey Ford et al. eds., 1904-37).

A modern study of Washington’s use of the militia in Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey concludes that, while the militia usually could not, by itself, defeat the Redcoats in an open field battle, it was essential to American success:

Washington learned to recognize both the strengths and the weaknesses of the militia. As regular soldiers, militiamen were deficient. . . . He therefore increasingly detached Continentals to support them when operating against the British army. . . . Militiamen were available everywhere and could respond to sudden attacks and invasions often faster than the army could. Washington therefore used the militia units in the states to provide local defense, to suppress Loyalists, and to rally to the army in case of an invasion. . . . Washington made full use of the partisan qualities of the militia forces around him. He used them in small parties to harass and raid the army, and to guard all the places he could not send Continentals. . . . Rather than try to turn the militia into a regular fighting force, he used and exploited its irregular qualities in a partisan war against the British and Tories.

Mark W. Kwasny, Washington’s Partisan War: 1775-1783, at 337-38 (1996). Thus, in 1777, when New Jersey was a major theater of the war, General George Washington implored the New Jersey county militias “by all you hold dear, to rise up as one Man, and rid your Country of its cruel invaders. . . . [T]his can be done by a general appearance of all its Freemen armed and ready to give them opposition. . . . I am convinced every Man who can bear a Musket, will take it up.” 10 Writings of George Washington, at 90.

Over a decade later, President George Washington’s first State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress urged that “A free people ought not only to be armed but disciplined; to which end a uniform and well digested plan is requisite.” 1 Journal of the Second Session of the Senate 103 (1820). Congress finally passed militia acts in 1792, organizing the Militia of the United States. As a practical matter, extensive militia training was beyond the capability of the small federal government, so training remained the responsibility of state and local governments.

While Washington strongly supported Americans taking up arms to defend their inherent rights, he strongly opposed the use of arms over transient political disputes. So in 1794, President Washington called forth the state militias to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania. Indeed, Washington was the only American President to personally command the military in the field while he was President.

Washington obeyed the statutory command that before actually using the militia, “the President shall … by proclamation, command such insurgents to disperse, and retire peaceably to their respective abodes, within a limited time.” First Militia Act of 1792, 1 Stat. 264 (1792). With the appearance of George Washington in command of a force of 13,000, the Whiskey Rebellion collapsed without need for fighting. Of course no one made any effort to prohibit the rebels’ from possessing firearms.

Like most land-owning Virginians, George Washington was an enthusiastic hunter. He was also a gun collector, particularly prizing a pair of pistols given him by the Marquis de Lafayette, and another pistol he received in 1755 from British Major General Edward Braddock, during the French & Indian War. This latter pistol was Washington’s sidearm during the Revolution.

Like all men, including great ones, Washington had some of the character flaws typical of the men of his time. Americans who celebrate Washington’s Birthday do not imagine that he was perfect; we do recognize that his patriotism, leadership, and rectitude are worthy of admiration. Whether we celebrate on Washington’s actual birthday of February 22, or on the third Monday in February (pursuant to a congressional act in 1971), we honor the ethos of responsible firearms ownership that made American independence and liberty possible.

Note: some of this essay is taken from Nicholas J. Johnson, David B. Kopel, George A. Mocsary, & Michael P. O’Shea, Firearms Law and the Second Amendment: Regulation, Rights, and Responsibilities (Aspen/Wolters Kluwer, 2d ed. 2017).

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2u6SzjD

via IFTTT

President Trump’s recently announced expanded travel ban policy has most of the same moral, policy, and constitutional flaws as his previous travel bans. Nonetheless, the conventional wisdom holds that there is little, if any prospect of successfully challenging it in court, because the most obvious arguments against it were rejected by the Supreme Court in Trump v. Hawaii, which ruled against legal challenges to the previous travel ban policy, of which the new one is an expansion. In that ruling, a 5-4 majority rejected both the argument that the travel ban was unconstitutional because motivated by Trump’s anti-Muslim animus, and the argument that it violated federal law forbidding discrimination on the basis of nationality in immigration visas.

While I think these holdings were terrible mistakes, I agree it iss unlikely that the conservative majority on the Supreme Court will overrule or cut back on Trump v. Hawaii in the near future. But it doesn’t follow there is no plausible way to challenge the expanded travel ban in court. To the contrary, both the previous travel ban policy and the new expanded version are vulnerable to constitutional challenge on a basis that was never even considered in Trump v. Hawaii: nondelegation. And it’s a basis that could potentially prove appealing to at least some of the very same conservative justices who were crucial to the majority in Trump. Liberal justices might support it too.

Nondelegation is the idea that Congress cannot delegate legislative power to the executive branch. The Constitution gives legislative power to Congress, not the president. Thus, there must be some limit to Congress’ ability to give the latter the power to determine what is or is not illegal. For example, it would surely be unconstitutional for Congress to give the president the power to ban any private activity he wants, so long as he decides doing so would be in the public interest.

Where to draw the line between legitimate discretion and impermissible delegation is a hard issue that has bedeviled judges and legal scholars. For a long time, in fact, the conventional wisdom was that the Supreme Court had no interest in giving nondelegation doctrine any teeth. But last year’s ruling in Gundy v. United States shows that at least four conservative justices are interested in enforcing the doctrine more robustly than has so far been the case. Indeed, even the four liberals may be willing to give it at least some modest teeth- enough, as we shall see, to place the travel bans in peril.

As interpreted by the majority opinion in Trump v. Hawaii, federal law grants the president virtually unlimited discretion to exclude immigrants and other potential entrants into the United States, for almost any reason he wants. If that doesn’t qualify as an unconstitutional excessive delegation, it is difficult to see what does.

Both the travel ban at issue in Trump v. Hawaii and the new expansion thereof on 8 USC Section 1182(f), which gives him the power to bar entry into the US by any foreign national whom he deems to “detrimental to the interests of the United States.” Here’s the full text:

Whenever the President finds that the entry of any aliens or of any class of aliens into the United States would be detrimental to the interests of the United States, he may by proclamation, and for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or nonimmigrants, or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.

In Trump v. Hawaii, Chief Justice John Roberts’ interprets this language as giving the president unconstrained power to exclude any aliens he wants for any reason, so long as he finds that their entry would be “detrimental to the interests of the United States”:

By its terms, §1182(f ) exudes deference to the President in every clause. It entrusts to the President the decisions whether and when to suspend entry (“[w]henever [he] finds that the entry” of aliens “would be detrimental” to the national interest); whose entry to suspend (“all aliens or any class of aliens”); for how long (“for such period as he shall deem necessary”); and on what conditions (“any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate”)…..

The Proclamation falls well within this comprehensive delegation. The sole prerequisite set forth in §1182(f ) is that the President “find[ ]” that the entry of the covered aliens “would be detrimental to the interests of the United States.”

I would add that Section 1182(f), as interpreted by the Court, does not limit what qualifies as an “interest” justifying an entry ban, and does not require the government provide any evidence that a travel ban would actually advance that interest. Indeed, in Trump v. Hawaii, the Court accepted a highly dubious national security rationale without any meaningful scrutiny.

The Court also (wrongly in my view) rejected claims that the scope of discretion granted by Section 1182(f) was narrowed by later federal laws barring nationality discrimination in the issuance of immigration visas. The analysis here relies on what seems to me a specious distinction between visas and the right to enter the United States, ignoring the fact that securing the latter is the whole point of acquiring the former. But, regardless, this virtually unconstrained view of Section 1182(f) was adopted by the Supreme Court.

Josh Blackman, a leading academic defender of the Trump v. Hawaii ruling, suggests that the Court’s interpretation of Section 1182 gives the president the power to effectively eliminate entire categories of immigration visas authorized by Congress, simply by denying their recipients entry into the United States. If he’s wrong about that, it’s not immediately clear why.

As already indicated, the nondelegation issue was not raised by the plaintiffs in Trump v. Hawaii, and not considered by the Court. A key reason why is that few thought that a revival of nondelegation constraints was a realistic possibility. Things are different, however, after last year’s ruling in Gundy v. United States, where Justice Neil Gorsuch authored an opinion on behalf of three conservative justices arguing for just that. A fourth conservative justice—Samuel Alito, did not join Gorsuch’s dissent, but did indicate in a concurring opinion that he is open to strengthening nondelegation doctrine in future cases. Justice Brett Kavanaugh did not participate in Gundy, because it was argued during the period when his nomination to the Court was held up in the Senate due to accusations of sexual assault. But conventional wisdom among legal commentators is that he too might well be sympathetic to the ideas laid out by Gorsuch.

On Gorsuch’s reasoning, which he backs with extensive Founding-era evidence, “the framers understood [the legislative power] to mean the power to adopt generally applicable rules of conduct governing future actions by private persons.” Only Congress has the authority to do that. As interpreted in Trump v. Hawaii, Section 1182(f) gives the president the power to do just that: he can adopt virtually any “generally applicable” rules he wants restricting the entry of non-citizens into the US. And, in the process, of course, he also enacts rules restricting the liberty of US citizens who want to form business, educational, and other types of contacts with these potential immigrants.

Elsewhere in his opinion, Gorsuch suggests that Congress can still “authorize executive branch officials to fill in even a large number of details, to find facts that trigger the generally applicable rule of conduct specified in a statute, or to exercise non-legislative powers.” But Section 1182(f), as interpreted in Trump v . Hawaii, clearly goes beyond that. It does not merely give the president the power to “fill in details” or find specific facts that “trigger” a “generally applicable rule” enacted by Congress. Instead, the president himself can make the rules simply by making assertions about what is in the national “interest,” and there is no requirement that he provide any specific type of factual evidence to back those assertions.

It is pretty obvious that the currently dominant interpretation of Section 1182(f) violates Gorsuch’s definition of nondelegation. But it is so sweeping that it likely also violates the more permissive approach adopted by Justice Elena Kagan in her plurality opinion on behalf of the four liberal justices.

In that opinion, Kagan attaches some very modest, but potentially real teeth to the “intelligible principle” standard that previously governed nondelegation cases, and had been thought to impose almost no constraint on grants of discretionary power to the executive. She recognizes that “we would face a nondelegation question” if the statute challenged in that case gave the president “‘unguided’ and ‘unchecked’ authority” to decide which sex offenders should face criminal penalties for failing to sign up for a national registry under Sex Offender Registration Notification Act (SORNA). But she—and the other liberals—concluded that there was no such problem with the relevant provision of SORNA because “[t]he text, considered alongside its context, purpose, and history, makes clear that the Attorney General’s discretion extends only to considering and addressing feasibility issues.”

In my view, this approach is still too permissive, and—for reasons well-articulated by Gorsuch—it is probably based on a flawed interpretation of SORNA. Regardless, the Court’s interpretation of Section 1182(f) violates Kagan’s standards. Under that approach, the president is indeed give “unguided and unchecked” authority to exclude whatever aliens he wants, for almost any reason he wants, and his discretionary power certainly is not limited to determinations of “feasibility” or any other specific factual issue. Indeed, it’s hard to conceived of a broader delegation of power than one that gives the president the power to determine the legality of a huge swathe of private conduct solely based on his unsupported assertion that restrictions are in the “national interest,” without any limitations on what qualifies as such an interest. That kind of delegation flunks both Gorsuch’s test and Kagan’s.

Some argue that nondelegation rules should be stricter in cases where criminal penalties are at issue. If so, 1182(f) qualifies. Illegal entry into the United States is a federal crime (albeit only a misdemeanor for a first time offense). Presidential power under Section 1182(f) includes the authority to criminalize entry by large categories of foreign citizens whose entry would otherwise be legal. In his dissent in Gundy, Justice Gorsuch correctly notes that the challenged provision of SORNA “hand[s] off to the nation’s chief prosecutor the power to write his own criminal code.” At least as interpreted in Trump v. Hawaii, Section 1182(f) hands off to the president the power to write his own immigration code, which also happens to include criminal penalties.

In sum, if Trump v. Hawaii’s interpretation of Section 1182(f) is correct, then Section 1182(f) is an unconstitutional delegation. At the very least, it suggests that a nondelegation challenge to Trump’s travel bans is worth trying. And, as noted above, both the earlier and expanded versions of the travel ban depend on presidential power under Section 1182(f). If it gets invalidated, all or most of the travel ban policy falls with it.

Faced with a strong nondelegation challenge, the courts could choose to give Section 1182(f) a narrower interpretation rather than striking it down outright. If so, that would likely still be a victory for opponents of the travel ban, as it is unlikely it can be narrowed significantly without jeopardizing at least some large parts of the travel ban. It could also set a valuable precedent for future nondelegation cases.

Striking down or limiting Section 1182(f) would not require the Court to undertake the difficult task of developing a comprehensive theory of nondelegation. It would be enough to say that giving the president virtually boundless discretion to bar entry into the United States is a bridge too far.

I do not claim that this nondelegation argument guarantees victory. Any constitutional principle that hasn’t been meaningfully enforced for a long time rests on somewhat shaky ground unless and until the courts show they are serious about it. There is the possibility that a majority of the justices aren’t really serious about enforcing nondelegation.

It is also possible one or more conservative justices will decide that immigration policy is an exception to nondelegation, just as it has been previously held to be an exception to many constitutional individual rights that constrain other federal powers. If that happens, the loss of conservative votes could potentially be offset by liberal justices willing to meaningfully enforce the strictures in the Kagan opinion. But, we cannot know for certain that the latter mean what they say until it comes to the crunch and they actually strike down a law for violating these rules.

That said, both conservative judges and liberal ones have some real incentives to enforce nondelegation here. For the conservatives, carving out exceptions to nondelegation in policy areas where it seems convenient for conservative ends is almost guaranteed to ensure that liberals will never recognize nondelegation as a meaningful, neutral constraint on executive power. And a legal doctrine supported by only one side of the political spectrum is unlikely to prosper for long. By contrast, using nondelegation to strike down a law favored by conservatives would send a strong signal in the opposite direction: that nondelegation isn’t “just for conservatives.”

For their part, liberals may potentially be willing to reconsider unconstrained delegation in an era where that power is likely to be wielded, at least some of the time, by Republican presidents hostile to immigration, and to some of the racial, ethnic, and other groups whom liberals see as most in need of protection against government power.

Such considerations have led many liberals to relax their previous opposition to judicial enforcement of constitutional federalism, and indeed to rely heavily on federalism principles in numerous successful challenges to the Trump administration’s policies targeting sanctuary cities. Perhaps nondelegation will follow a similar trajectory. At the very least, it’s a possibility worth taking seriously.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/38AQiMN

via IFTTT

Harris County District Judge Kelli Johnson last week declared Steven Mallet, who served 10 months in jail after he was arrested for selling crack cocaine in 2008, “actually innocent.” Earlier this month, Harris County District Judge Ramona Franklin reached the same conclusion regarding Mallet’s brother, Otis, who served two years for his alleged involvement in the same transaction.

Both men were arrested by Gerald Goines, the veteran narcotics officer who spearheaded the January 2019 drug raid that killed a middle-aged couple, Dennis Tuttle and Rhogena Nicholas, in their home on Harding Street. Goines invented a heroin purchase by a nonexistent confidential informant to justify that raid, which discovered no evidence of drug dealing.

In response to the false testimony identified in the cases against the Mallet brothers, Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg has more than doubled the time period covered by her re-examination of cases involving Goines and other officers in Squad 15 of the Houston Police Department’s Narcotics Division. “Because of the revelations involving the Harding Street raid, District Attorney Ogg initiated a review of 14,000 cases that Goines and his squad worked over the last five years,” a press release from Ogg’s office says. “With the Mallet cases now being revealed, that review is stretching further back, to 2008.”

If the squad handled 14,000 cases in five years, the total number of potentially questionable cases since 2008 is probably something like 30,000, and it’s by no means clear that misconduct by narcotics officers began that year. “The sheer number of the cases that could be involved is daunting,” Ogg said. “Even though it is challenging, our mandate is to always and continually seek justice.”

Ogg’s review is not necessarily limited to cases involving “actually innocent” defendants. “Justice dictates that we continue going through questionable cases and clearing people convicted solely on the word of a police officer we can no longer trust,” she said. “When the only evidence of criminal culpability is the testimony of an untrustworthy officer, we are going to work as fast as possible to right the situation.”

Prosecutors already have dismissed dozens of pending cases involving Goines. Between 2008 and 2019, according to Ogg’s office, Goines worked on 441 cases, which led to 263 convictions of 234 defendants. “The claims that are going to tend to be successful are going to be these one-witness claims,” Josh Reiss, head of Ogg’s post-conviction unit, told The Houston Chronicle. “How many of those one-witness claims there are in these 263, I don’t know. It’s going to take some time to dig in, but that’s what we’re going to do.”

The potential problems may extend far beyond the cases initiated by Goines, who faces state murder charges and federal civil rights charges as a result of the Harding Street raid. Another member of Squad 15, Steven Bryant, faces state and federal charges for backing up Goines’ fictitious account of sending a confidential informant to buy heroin from Dennis Tuttle. Given the evidence that Goines, who was employed by the Houston Police Department for 34 years, had been framing people since at least 2008, it seems likely that other officers are implicated in that pattern of dishonesty, which would make their testimony untrustworthy as well.

Otis Mallet, who was convicted by a jury, served two years of an eight-year sentence before he was released on parole. He has always maintained his innocence. Steven Mallet spent 10 months in jail before pleading guilty as part of a deal that did not require him to spend any more time behind bars. “He pled guilty because he had been in jail for 10 months and they were offering him a deal basically for time served,” said public defender Bob Wicoff. “This happens a lot where people have to get out and resume their lives. They [have] jobs and families, [so] they plead guilty even when they’re not just to get out.”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2SRz1Ij

via IFTTT

President Trump’s trade-related initiatives against China deserve broad public support.

That was the resolution of a public debate hosted by the Soho Forum in New York City on February 4, 2020. It featured Stephen Moore of the Heritage Foundation and Gene Epstein of the Soho Forum. Comedian Dave Smith moderated.

It was an Oxford-style debate, in which the audience votes on the resolution at the beginning and end of the event; the side that gains the most ground is victorious. Moore prevailed by convincing 21.51 percent of audience members to change their minds. Epstein convinced 13.98 percent.

Arguing for the affirmative was Stephen Moore, distinguished visiting fellow for the Project for Economic Growth at the Heritage Foundation. Moore is also a senior economic contributor for FreedomWorks and the founder of the Club for Growth.

Gene Epstein argued for the negative. Epstein, former economics editor of Barron’s, is co-founder and director of the Soho Forum.

The Soho Forum, which is sponsored by the Reason Foundation, is a monthly debate series at the SubCulture Theater in Manhattan’s East Village.

Produced by John Osterhoudt.

Photo: Brett Raney

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2UZpwd2

via IFTTT

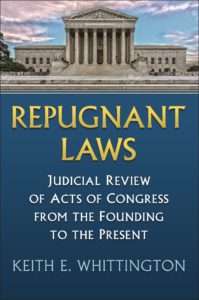

I’m pleased to note that on Friday, February 21, at 9:00am, the American Enterprise Institute will be hosting a book forum on my recent book, Repugnant Laws: Judicial Review of Acts of Congress from the Founding to the Present. Adam White will be providing commentary.

I’m pleased to note that on Friday, February 21, at 9:00am, the American Enterprise Institute will be hosting a book forum on my recent book, Repugnant Laws: Judicial Review of Acts of Congress from the Founding to the Present. Adam White will be providing commentary.

The book provides a political history of how the U.S. Supreme Court has limited—and facilitated—congressional power across its history. Along with the book, I’ve released a new comprehensive of dataset of cases in which the Court has substantively evaluated the constitutionality of an application of an act of Congress.

The event is open to the public, and registration for those in the DC area can be found here. If you prefer to watch the video from the comfort of your secure bunker in an undisclosed location, you can do so live or on video a few hours later.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2V59RIS

via IFTTT

2/17/1801: House of Representatives breaks tie in Electoral College, and selects Thomas Jefferson as President.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2OYMk8E

via IFTTT

In 1971 the yippie radical Abbie Hoffman wrote a book advocating resistance to government, capitalism, and the “Pig Nation.” Steal This Book advocated shoplifting, squatting, and other methods of living off other people for free. The title and the contents made the manuscript hard to peddle. But when it finally got a publisher it sold well in bookstores, which was good for Hoffman financially. It turns out that most people want to live off other people not by stealing but by paying a fair price earned by their own labors. Hoffman remarked, “It’s embarrassing when you try to overthrow the government”—and capitalism—”and you wind up on the Best Seller’s List.”

I want you to steal what the lawyers self-interestedly call “intellectual property”: Hoffman’s book or my books or E=mc2 or the Alzheimer’s drug that the Food and Drug Administration is “testing” in its usual bogus and unethical fashion. I want the Chinese to steal “our” intellectual property, so that consumers worldwide get stuff cheaply. I want everybody to steal every idea, book, chemical formula, Stephen Foster lyric—all of it. Steal, steal, steal. You have my official economic permission.

What?! A liberal (in the classical sense) wants people to steal? You bet. Here’s why. An idea, after it is produced, has no opportunity cost. If one more person reads Hamlet, there’s no less of it available for the next person. That’s not true of, say, your house. If the neighbors treat your house as common property, there’s less of it for you to use. George is in the bathroom right now. Sorry.

It’s true of your labor, which also has an opportunity cost—an alternate use necessarily forgone—to you. If you become a slave, you can’t use your own self. The master in Kentucky gets those hours in the field away from the little cabin floor, yet he doesn’t pay you for their opportunity cost.

The correct price for such scarce items is their opportunity cost, because then, as Adam Smith said, “As every individual…endeavors as much as he can both to employ his capital [and labor and land and other items with opportunity cost so] that its produce may be of the greatest value, every individual necessarily labors to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can.”

But ideas have no opportunity cost. So the optimal price, socially speaking, is zero. That’s the correct application of the invisible hand. It’s like the Brooklyn Bridge. On the day it opened on May 24, 1883, the correct price to charge another walker across the bridge was zero. The additional walker causes trivial wear to the bridge, and unless the bridge was congested, she causes no opportunity cost.

“Aha!” you reply. “But what about the cost to make the bridge in the first place, or the cost of supporting Shakespeare while he writes Hamlet, or the cost of research and, umm, marketing costs such as trips for doctors and their families for conferences in Hawaii to get a new drug for Alzheimer’s? And you call yourself an economist!”

Yes, all that is true. If people are going to get the bridge or Hamlet or the drug, someone has to pay for it. There’s no free lunch. It’s the central dilemma in any system of rights for intellectual property, or anything else with costs up front but no opportunity cost in use.

There’s no trick solution that works qualitatively, such as “have a patent system.” Too bad. Life is hard. But the rules that apply to property with an opportunity cost simply don’t apply to ideas.

Mathematically speaking, assuming you want to maximize national income, there’s a solution. In principle, for each particular example of a cancer drug or a romance novel or an idea for a printed circuit, there’s an optimal price. To get the highest total national income, all you have to do is find out what term of years for a patent or copyright is optimal for that particular example. That “solution” is like the economist’s solution for opening the can of beans left to a shipwrecked survivor. (To open it, assume you have a can opener.) It’s the same as the “solution” to the numerous market imperfections that, say, the economist Joseph Stiglitz believes he sees all around him. To fix them, says Stiglitz, assume you have a perfect government.

An irritating case of not understanding the dilemma is the practice by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) of erecting a paywall to charge for its papers written in the national interest. The considerable charge earns a trivial portion of the costs of producing the papers. Stiglitz’s salary is way larger than what’s collected. And once the paper is written, the marginal social cost of releasing it is, of course, zero. So according to the principles of pricing figured out in economics a century ago, which Stiglitz teaches at Princeton, the price should be zero. I tried a couple of times to get my friends on the board of the NBER to relent in their anti-economic practice, but they were beyond embarrassment. Being the NBER means you don’t have to take seriously either the national or the economic.

There’s a more serious counterpoint, made by the economist Steven Horwitz of Ball State University. Namely, that a pastrami sandwich made just the disgusting way you like it, with ketchup, once produced and about to be handed over to you at the deli, also has no opportunity cost. The reply to Horwitz is to retreat to constitutional principles. Namely, the system that gives the best overall result. We want sandwiches to be produced even in the disgusting way you want them, and in order to get the deli to do so we need to have a rule that you have to pay for it.

Another counterpoint is the trade secret. After you’ve thought of it, the social cost of giving it up is zero. Are you required to give it up? No, on a still deeper constitutional principle: the right not to be enslaved. No wonder Aristotle got that exact point wrong in a society in which the nonslaves deemed slavery to be just fine.

We liberals since the 18th century have denied slavery. The U.S. copyright of fully 70 years from the death of the creator makes people pointlessly enslaved to the heirs of Walt Disney. In Hoffman’s 1987 trial for trespass while protesting the activities of the CIA at the University of Massachusetts, he quoted Tom Paine: “Every age and generation must be as free to act for itself, in all cases, as the ages and generations which preceded it. Man has no property in man, neither has any generation a property in the generations which are to follow.”

Right on, brother.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2SyLSjT

via IFTTT

The Alabama Department of Human Resources took Rebecca Hernandez’s baby away from her after a drug test administered to Hernandez four hours after she gave birth showed she had opiates in her system. A later test showed no trace of drugs, and the state returned the child. Her doctor found Hernandez ate poppy seed bread the day before she gave birth and thinks that produced a false positive. The doctor says same-day drug tests are more prone to error and hospitals should rely only on lab tests before alerting the state to any problems. The hospital where Hernandez have birth, Crestwood Medical Center, said in a statement that it is “committed to following the law and regulatory requirements as well as ensuring the health and safety of our patient.”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2HxyBlj

via IFTTT