The Loneliest Americans, by Jay Caspian King, Penguin Random House, 272 pages, $27

Jay Caspian Kang’s life story is both extraordinary and somewhat normal for families like his.

His parents’ family had roots in North Korea, although they fled to the South in the leadup and aftermath of what is known in America as the “Korean War.” Upon getting married, his father and mother moved to the U.S. They arrived with relatively humble means, yet his parents enjoyed significant social mobility and their children flourished in the U.S. too. Although his path was far from straightforward, Kang ultimately attained a B.A. from an elite liberal arts college (Bowdoin) and an MFA from an Ivy League university (Columbia). He published a well-regarded novel. He worked as a reporter and/or editor for ESPN, The New Yorker, Vice, and elsewhere before joining The New York Times, where his columns are consistently great.

His latest book, The Loneliest Americans, draws on his own family’s story and his reporting over the years to explore what it means to be Asian in America today. It deftly situates his own life and work within the broader journey of Asians in America, from the mid-1800s through the present. The book was inspired by the birth of his daughter, whose mother is non-Asian. Thinking about how his child would come to navigate her hyphenated identity led Kang to reflect on his own struggles with these questions, and on the struggles of his peers, and on those of the generations that came before.

A New Identity

“Asian American” as an identity was born in Berkeley in 1968. The term was coined by the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA), which sought to forge a new pan-ethnic coalition, modeled on the black power movement (and the nascent Chicano movement), to address challenges that different Asian groups held in common.

Through the 1960s, one thing most of the largest Asian groups in America shared was an intimate connection to U.S. military intervention abroad, from the pacification and eventual conquest of Hawai’i, to the colonization of the Philippines, to World War II and the subsequent occupation of Japan (where roughly 55 thousand U.S. soldiers remain stationed to this day), to the Korean War (nearly 29 thousand U.S. troops continue to be stationed in Korea) and the Vietnam War (where U.S. withdrawal was accompanied by ambitious refugee resettlement programs).

Through the 1960s, one thing most of the largest Asian groups in America shared was an intimate connection to U.S. military intervention abroad, from the pacification and eventual conquest of Hawai’i, to the colonization of the Philippines, to World War II and the subsequent occupation of Japan (where roughly 55 thousand U.S. soldiers remain stationed to this day), to the Korean War (nearly 29 thousand U.S. troops continue to be stationed in Korea) and the Vietnam War (where U.S. withdrawal was accompanied by ambitious refugee resettlement programs).

Large numbers of Asians became Americans in the wake of these conflicts by marrying one of the U.S. soldiers occupying their home country. Family unification policies eventually allowed parents, siblings, and other relatives of military spouses to come over as well. These migrants ended up living, and building rich community ties, on or near military bases. Other Asians directly served in the military themselves throughout U.S. history, with many attaining naturalized citizenship in exchange for fighting on America’s behalf.

Consequently, from the late 1800s through the mid-1960s, Asian America had a particularly intense, ambivalent, and complicated relationship to the United States and its war machine.

Beyond the invasions and occupations abroad, the U.S. has a long and shameful history of domestic oppression, exploitation, exclusion, and violence against Asians. In many respects, Chinatowns and Japantowns are living monuments to this history. (As Kang notes, Koreatowns were a bit different. They were established later, as a positive project, to carve out an ethnic enclave for Korean Americans that rivaled or exceeded the Chinatowns and Japantowns that were flourishing in many U.S. cities at the time.)

The AAPA constructed an “Asian American” identity around this common history, organizing students of Asian ancestry to resist discrimination at home and military adventurism abroad. But from the outset of the project, there were tensions along the lines of ethnicity and class. And before long, even the common threads of war and domestic oppression would grow more tenuous.

Kang details how immigration was tightly restricted during the period that American oppression, violence, and exclusion of Asians was most pronounced. At the time the U.S. began to open up again, the most egregious hostility and restrictions had been done away with. Indeed, one reason the laws could be liberalized is because the public had grown less hostile towards immigration in general, and to Asian Americans in particular, in the period following World War II.

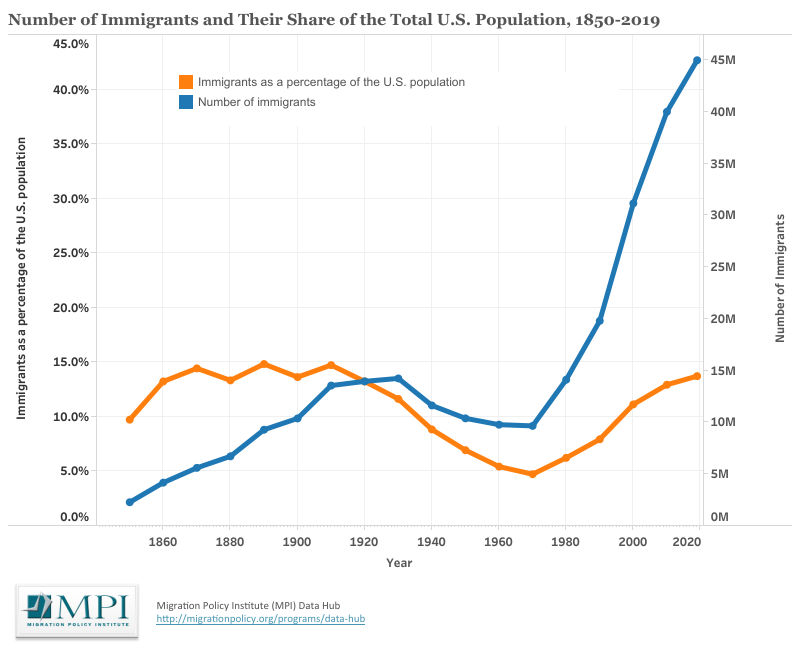

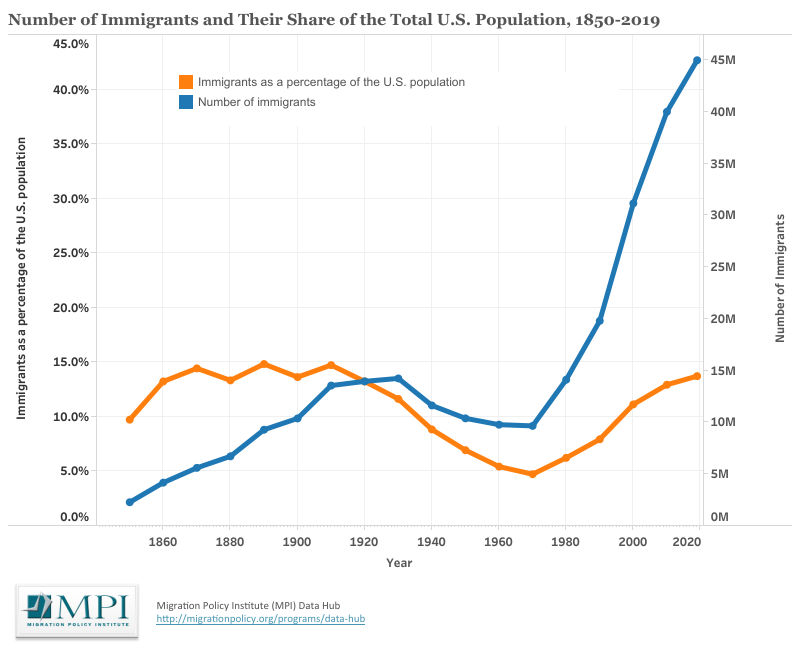

Despite this liberalization, when the 1965 Hart-Cellar Act relaxed U.S. immigration restrictions, the White House downplayed its likely impact. President Lyndon Johnson insisted that the legislation wasn’t that big of a deal and that it wouldn’t change the fabric of U.S. society much in the long run. He was wrong.

Today, immigrants’ share of the total U.S. population is approaching levels not seen in more than a century. Asian migrants have been key drivers of that growth. Through the 1970s and ’80s, a plurality of all U.S. immigrants hailed from Asia. Asian migrants were briefly outpaced by immigrants from Latin America in the ’90s and early ’00s, but since 2008 a plurality of new migrants to the United States have been Asian once again. Since 1965, Asian Americans have risen from less than one-half of one percent of the U.S. population to more than 6 percent (according to 2020 U.S. Census estimates). The total number of Asians in America today is roughly 20 times what it was when Hart-Celler was signed into law.

Consequently, for most Asian Americans, their family history in the U.S. begins after 1965. In Kang’s verbiage, they are children of Hart-Celler.

These post-Hart-Celler waves of migrants generally had no direct connection to the worst of America’s mistreatment of Asians. Neither they nor their parents nor their grandparents nor any direct ancestor experienced internment, legal exclusion, or the most vicious strains of racism and racialized violence against Asians in America.

Moreover, after the fall of Saigon in 1975, U.S. military operations largely pivoted away from East Asia, growing increasingly focused on the Middle East and North Africa instead. Immigration patterns also shifted away from Asian countries where the U.S. had waged major conflicts. In recent decades, Chinese and Indian immigrants have come over in much higher numbers than migrants from other Asian countries, with these two groups now amounting to nearly half (45 percent) of the contemporary Asian-American population. As a function of these changes, the imprint of the United States military and its campaigns abroad—both the scars and the ties—have grown markedly less pronounced within America’s Asian population as well.

For the children of Hart-Celler, America largely represented freedom, opportunity, and hope. For all its flaws, America was less corrupt, nepotistic, and parochial than the countries they hailed from. There were fewer barriers to mobility. There was more stability and opportunity. Many from ethnic or religious minority subgroups faced markedly less persecution in the U.S. than they did in their countries of origin. The post-1965 immigrants flocked to the U.S. because they believed in the American dream, and their children often embody the realization of that dream, even if they come to hold a more jaundiced view of the U.S. than their parents.

Luxury Beliefs

Generally speaking, Asian migrants have been able to build comfortable lives in America and to see their children flourish here. According to several conventional metrics of success, Asian Americans have managed not just to match whites on average but to exceed them. But not all Asian Americans have been able to flourish the same way. Asians are the most socioeconomically polarized racial and ethnic bloc in the U.S., with particularly stark divisions along the lines of national origin.

Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino, Taiwanese, Thai, Malaysian, Sri Lankan, Indonesian, Pakistani, and Indian Americans all enjoy educational attainment rates and average household incomes that are significantly higher than overall U.S. averages. Vietnamese Americans are roughly at level with the U.S. averages on these measures. Bangladeshi, Hmong, Cambodian, Burmese, Bhutanese, and Laotian Americans, however, have much smaller and less-established populations in the U.S. Consequently, they do not have the same access to ethnically oriented networks and infrastructures to help them, and they often migrate to the U.S. with lower levels of pre-existing “cultural capital” than other Asian subgroups as well. These populations tend to have household incomes and/ or rates of educational attainment that fall significantly below the U.S. average—and as a result, they tend to be absent from most discussions about Asian America. That discourse, Kang argues, is fundamentally by and for elites.

Since most contemporary Asian Americans have no direct connection to America’s history of violence, marginalization, and oppression, they tend instead to learn about it in college: in their classes, through participation in affinity groups, through engagement with peers and consumption of “woke” media. The “Asian American” identity was born in college, and remains tied heavily to institutions of higher learning.

As Kang notes, being imbibed into the history of violence and exclusion against Asians in the U.S. at the same time one is pursuing professional credentials tends to have somewhat contradictory effects. It alienates Asian-American elite aspirants from America’s preferred self-narratives even as it helps them “see” themselves more clearly in U.S., to feel like they have a voice and a place here, to understand the deep and longstanding role people “like them” have played in American society. It enhances Asian Americans’ sense of precarity and victimhood even as it helps them fit in better among the elites they hope to join.

Indeed, Kang argues, one reason college-educated Asian Americans gravitate toward this discourse is because they come to recognize that upward mobility in the knowledge economy is largely contingent on pleasing white liberal gatekeepers—on mirroring their values and fitting into their worldviews. Leaning into “woke” identitarian discourse is recognized as a reliable means of demonstrating that one has the educational pedigree and moral character to belong among the Harvard, Google, New York Times, and McKinsey & Co. crowd. Conspicuously lamenting various forms of systemic disadvantage can serve as both a signal and a reinforcer of one’s (actual or aspirational) elite status.

For instance, Asian Americans affiliated with prestigious knowledge-economy institutions tend to express strong support for race-based affirmative action (which, as practiced at elite colleges and universities, is widely perceived to disadvantage Asian applicants relative to people of other backgrounds). Likewise, although Asian Americans rely heavily on standardized testing to gain admittance to elite educational institutions, many of those who have successfully gained admission into those institutions express openness to abolishing standardized testing henceforth in the name of racial justice.

The social psychologist Rob Henderson has defined positions like these as “luxury beliefs.” For those who have already managed to get into their desired school, the persistence of affirmative action or the elimination of standardized testing would not adversely affect them. After all, they’ve already gained admittance. Indeed, the elimination of standardized testing may even help their children reproduce their class position. College essays (typically relied upon more heavily in lieu of standardized tests) tend to track parental socioeconomic status even more closely than SAT scores do. New immigrants hoping to break into elite institutions for the first time would find it far more difficult to outcompete the children of established Asian-American elites on admissions essays than on standardized tests. For incumbent Asian elites, then, an embrace of fashionable professional-managerial class ideas on affirmative action and testing costs them nothing and provides a range of benefits—from helping them fit in with liberal white peers to helping restrict and weaken competition from future cohorts of elite aspirants.

However, things look much different for first-generation Asian migrants hoping that their children will achieve mobility in the U.S. Or for those who went to college, but couldn’t get into the schools they wanted; who got a good job, but not the kind of job they hoped for. Or for those who imagine they might have attained had they made it into their target school—whose families are proud, but not the way they would have been if their child was an alumnus of Harvard, Princeton, or MIT. Among populations like these, Kang highlights, the widespread embrace of affirmative action, the elimination of standardized testing, etc. among already-successful Asians is often met with resentment.

It Gets Lonely Near the Summit

It is a particular subset of Asians in America that struggles with a hyphenated identity. Older, first-generation immigrants and those who are less educated and/or less affluent tend to understand themselves either as Americans who happen to be of (say) Korean ancestry or as Koreans who happen to live in America. They don’t wrestle over conjunctions like “Korean-American” and the contradictions contained therein. A pan-ethnic “Asian-American” identity that puts Koreans under the same umbrella as Mongolians, Indians, and Indonesians is even less meaningful or useful to them.

The notion that all these groups, plus Hispanics and black people in all their internal diversity, could be integrated into an even broader group, “people of color,” juxtaposed against whites, would seem even more absurd. First, because many migrants want themselves and their children to actually get along with whites and to be assimilated into the mainstream. Second, because in many communities where Asian Americans cluster, there are deep and longstanding tensions between people of Asian ancestry, Hispanics, and African Americans.

Kang provides an insightful survey of the persistent tensions and occasional solidarity between Asians and other minority groups in Chapters 3 and 6. He goes on to argue that, although hyphenated identities, race-making narratives and pan-ethnic appeals have little resonance for many Asians in America, they nonetheless feel urgent and deeply meaningful for younger Asian immigrants, second- and third-generation migrants, and current and aspiring professionals. Kang calls Asians in these latter categories “the loneliest Americans.”

They feel like an “other” in the U.S. but would often be out of place in the countries their families hail from as well. They don’t feel “white” and don’t aspire to become “white.” Yet although they are proud of their ethnic background, they also seek to transcend it. They strive aggressively to attain prestigious credentials and jobs, and often to move into predominantly white neighborhoods. Yet they simultaneously feel intense guilt, shame, and vertigo associated with social mobility, and with integration into elite institutions and predominantly white social circles. They face problems on the basis of their race and ethnicity, but they also recognize that their challenges may seem relatively trivial to others. For instance:

- They and their children generally attend especially great K-12 schools, but are regularly bullied, shunned, or exoticized therein. Although Asians tend to experience far less bullying overall than other racial or ethnic groups, they are among the most likely to be targeted for harassment specifically on the basis of their race and ethnicity.

- On average, Asian Americans possess the highest levels of educational attainment in America. But the most prestigious schools have de facto caps on Asian admissions in order to attain a sufficiently “diverse” student body, so Asians have to perform at a higher level than people of other backgrounds to have any shot at attending the very best institutions. Moreover, although the vast majority of young people from most Asian ethnic groups do go to college somewhere, those who wash out at high school tend to be significantly worse off than whites who possess similar levels of education.

- Those who attain a college degree tend to end up with good jobs. But Asians often face various forms of microaggressions in the workplace, and are often excluded from the positions at the very top of their organizations (a phenomenon called the “bamboo ceiling“).

- Despite being overrepresented within professional circles, Asian Americans tend to be significantly underrepresented in U.S. television, film, and literature. And they are often depicted in unfortunate ways when they are rendered visible. Asians also tend to be significantly underrepresented in local, state, and national elected offices.

- Asian Americans face racialized animus, albeit not to the same degree as other racial and ethnic groups. (A recent NBER study found that Asian Americans have been able to attain such extraordinary success relative to other minority populations in large part because, after WWII, they stopped being directly oppressed the way other racial and ethnic minorities continued to be.) Asians experience hate incidents, but significantly less often than other racial and ethnic groups—and these usually involve words, vandalism, and social shunning rather than direct physical violence. When direct physical violence does occur, Asian-American professionals are expected to conform with the prevailing practice of making a big deal about the race and ethnicity of the perpetrator when they happen to be white but making absolutely no mention of the race of the aggressor should they be non-white. In the wake of those attacks, they are expected to offer up sentiments of racial solidarity—even as many of those they seek solidarity with continue to view Asians as “privileged” minorities with problems less pressing than their own.

This is a key source of the “loneliness” Kang describes: Because Asian Americans are generally doing better than other racial and ethnic minority groups, and often better than the typical white American for that matter, it is difficult to get people to care much about their problems and their struggles. Insofar as they have internalized the prevailing ethos of the professional-managerial class, they often feel a bit of guilt or shame themselves for focusing on challenges Asians face in the U.S.

Many Asian Americans, particularly males, are growing hostile toward this state of affairs. Chapter 7 explores the rise of “radical” Asian movements blossoming in the United States, which tend to be heavily focused on preserving the means of social mobility for Asian migrants, pushing through the bamboo ceiling, asserting Asians’ rightful place in American culture and politics, and challenging adverse sexual dynamics among Asian men and women (where the latter are fetishized and heavily pursued by non-Asian men, while the former are often depicted and treated as non-sexual entities).

These movements tend to draw on a wild mélange of black nationalist ideology, “redpill” manosphere writings, and “woke” symbolic politics. Although they define themselves in opposition to the mainstream liberalism of most other Asian-American professionals (who are perceived to have sold out in a Sisyphean bid to gain acceptance among liberal whites), Kang astutely observes that the “radicals” are not as far removed from their adversaries as they seem to believe.

For instance, mainstream Asian elites often identify as “people of color” and express solidarity with others who do the same. Yet these alliances typically amount to little more than a multicultural elite engaging in negotiations and competition with white peers for more representation in The New York Times, Hollywood productions, the C-Suite, and the Ivy League. The “radicals” likewise remain centered overwhelmingly on professional-managerial class concerns: elite schools, bamboo ceilings, and so on. The people who take part tend to be highly educated and relatively affluent, just like their mainstream peers. They may “demand” rather than request respect and recognition—more in principle than in practice to date—but they remain just as preoccupied with the “white gaze.” (They seek respect and recognition from whom?) And they obsess about their position relative to whites with respect to the dating market, media and political representation, etc.

In the same way that much postcolonial literature ultimately remains fixated on “the West” and produces roughly the same image of power relations that orientalist scholarship did, the “radical” Asian movement presents itself as an alternative to professional-managerial Asian politics but is probably better understood as a variation of the same.

Working-class, older, and first-generation Asians, for their part, have been shifting toward the GOP recently (both during the Trump years and after). In other words, the growing political divide between knowledge-economy professionals and everyone else seems to be playing out within Asian-American circles just like it is in the public writ large. The “loneliest Americans”—who tend to be deeply enmeshed in the symbolic professions and consolidated in knowledge economy hubs—could find themselves even more isolated down the line.

Kang is persistent in trying to draw readers’ attention to the class dynamics at play in these discussions of racial and ethnic identity. For this reason and many others, his book provides an outstanding entry point for understanding where we are as a country today, how we got here, and where things might be headed. The book is technically “about” people of Asian ancestry, but the story of Asians in America is in many respects a story about America writ large.

The post First World Problems appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest https://ift.tt/g1moZST

via IFTTT

Through the 1960s, one thing most of the largest Asian groups in America shared was an intimate connection to U.S. military intervention abroad, from the

Through the 1960s, one thing most of the largest Asian groups in America shared was an intimate connection to U.S. military intervention abroad, from the