Revolving bail funds are the closest thing there is in activism to a perpetual motion machine. A bail fund steps in on behalf of a defendant to pay the bail bond set by a court. With bail paid, arrestees can go home, keep their jobs, and resist pressure to accept a plea deal in order to leave jail. As long as the defendants show up for their trial dates, the bail money is returned to the fund and can be used again and again and again, as long as bail exists.

That last is the reason that the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund (BCBF) blew up its own successful model in 2019. The organization announced it would stop paying individual criminal bails (though it would continue to pay immigrant detention bonds). The new focus would be ending cash bail, not ameliorating its effects.

New York is the only state to explicitly recognize and regulate nonprofit bail funds. The 2012 Charitable Bail Act codified how such groups could interact with the criminal justice system. Bail payers must be licensed by the state as bail bond agents, passing background checks and licensing exams. They may pay up to $2,000 worth of bail for defendants and may only assist defendants charged with misdemeanors, not felonies.

That means bail funds could not have paid the full bail of Kalief Browder, a 16-year-old boy charged with stealing a backpack in 2010, whose bail was set at $3,000. Unable to pay, he spent three years at Rikers Island awaiting trial, approximately two years of it in solitary confinement. He committed suicide after his release.

In 2018, when I began interviewing BCBF employees about their work, I asked Peter Goldberg, then the executive director, whether he hoped to see the Charitable Bail Act expanded so the fund could assist a broader range of people. He said no: The goal wasn’t to pay more bails. “The worst thing we could do is to normalize the system,” he told me. “Bail funds are not a solution to cash bail. We’re working to put ourselves out of business.”

Still, the case for the basic function of paying bail was compelling. “Many donors understand that if their son or daughter found themselves in this position—there’s no chance they’d spend the night in jail,” says Melissa Benson, at the time the BCBF’s director of development. Bail funds even attracted attention and money from the effective altruist movement, a constellation of individual donors and grant-making institutions who try to maximize the impact of their charitable giving. Most effective altruist causes are focused on global health and poverty—it’s easiest to quantify the value of malaria nets or direct cash transfers. The more you focus on the poorest and most vulnerable, the more cheaply you can save lives.

The revolving structure of a bail fund was part of the appeal for these donors. The money they give doesn’t get used up. As the Open Philanthropy Project noted in 2015, “the vast majority…of dollars donated revolves to help multiple cases and lives.” The next year, the Open Philanthropy Project directed a $404,800 grant to the BCBF. Buy a malaria net and the money can’t be used again, but bail fund money keeps working, bailing out prisoner after prisoner.

The Brooklyn Community Bail Fund is one of many such funds across the country. The Minnesota Freedom Fund and similar organizations attracted national attention after the death of George Floyd in 2020, with politicians such as then–California Sen. Kamala Harris promoting them as a way to support protesters. (In practice, protesters were a small share of the people assisted by these funds, whose biggest impact was for people who were accused of committing unnewsworthy crimes.)

Bail funds had looked like a way of outsmarting the system: Courts could keep setting bail, but a bail fund operated as a kind of nullification of the prosecutor’s recommendation and the judge’s decision. The revolving money seemed to many bail fund donors, including me, like a way of turning tragedy into farce. But the BCBF team had come to believe they’d essentially been conscripted into the carceral system they wanted to dismantle.

‘You Can’t Let It Continue’

In the run-up to the 2019 passage of bail reform in New York, the BCBF’s Carl Hamad-Lipscombe was working as a public defender. He heard legislators argue that abolishing cash bail was unnecessary, because groups like the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund solved the problem of bail already. “We were a crutch, holding up this situation we don’t believe in,” he said. Bail funds let politicians get the softer outcome they wanted without having to put their names to an attempt to change the law. The BCBF’s solution was to force lawmakers to confront the costs of the current system.

Goldberg believes that New York already has the tools it needs to do away with cash bail. At least on paper, he says, “New York already has an incredibly progressive bail statute.” Judges are free to choose from nine different forms of bail, but overwhelmingly, they use only two: cash bail and insurance company bonds. Courts also have the option to impose nonmonetary restrictions such as electronic monitoring, pretrial support programs, or a requirement that defendants give up their access to guns. Switching to one of these options requires only political will, not statutory permission.

No matter what, courts are supposed to choose the least restrictive means required to get a defendant to return for trial. When the overwhelming majority of defendants whose bail is paid by a bail fund—and who thus have none of their own money at stake—show up at trial, it undermines the premise that cash bail was the least-restrictive option available. Those defendants didn’t need to have money on the line in order to come back.

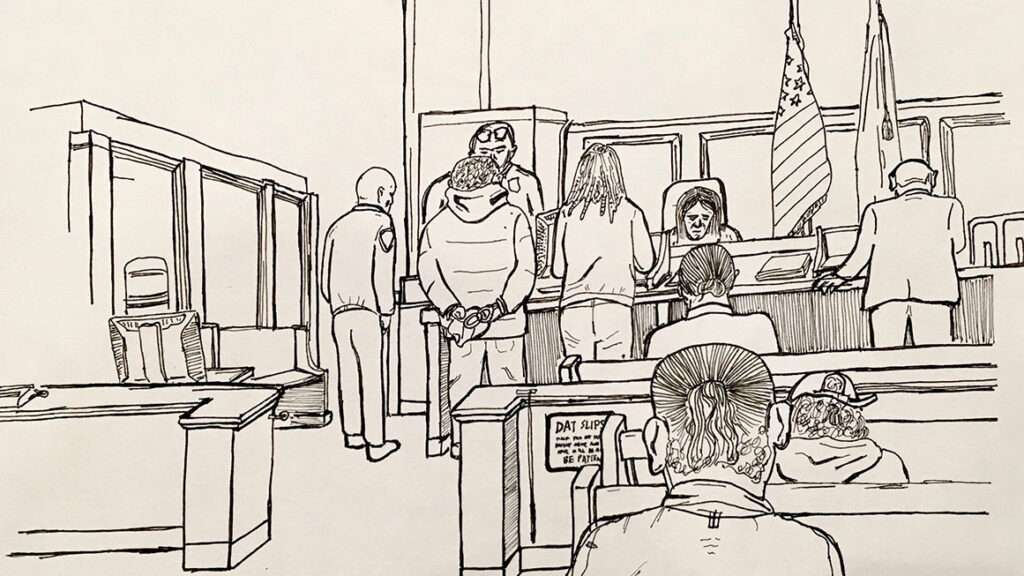

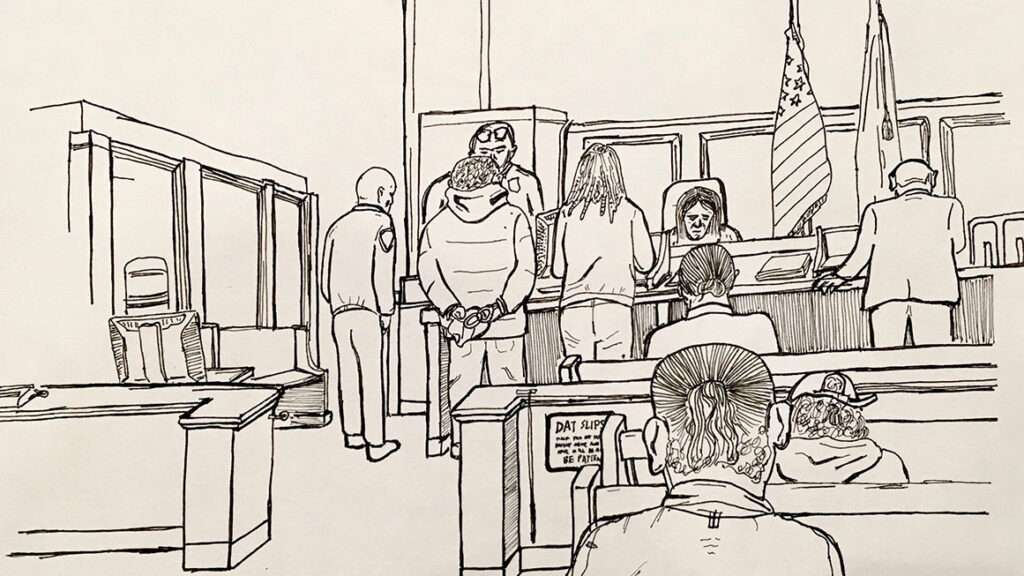

The BCBF keeps track of what options are available through its CourtWatch program, overseen for a time by Hamad-Lipscombe, who served as the fund’s director of advocacy and policy before succeeding Goldberg as executive director in June 2021. In nonpandemic times, court watchers trained through the program sit in courtrooms and tabulate data on arraignments and bails. They show up in bright yellow shirts, a visible reminder of their presence to everyone in the courtroom.

The goal, as Angel Parker, the CourtWatch NYC program coordinator, explained it to a group of prospective volunteers in March 2021, is “to collect and publish data about prosecutor behavior and compare what’s happening in the courtroom with publicly announced [district attorney] policies.”

Court watchers record the demographic details of defendants, what they’re charged with, and what recommendation the prosecutor makes. If a defendant has bail set, they note the amount. They also keep track of whether anyone in the courtroom explicitly addresses whether the defendant is a flight risk, whether the bail is the least restrictive way to ensure the defendant will return to court, and whether the defendant can pay the bail without undue hardship.

In a July 2020 report, the CourtWatch team noted that prosecutors and judges relied heavily on cash bail, even though they were supposed to use less restrictive means when possible. Seventy percent of defendants whose alleged crimes qualified for bail had bail set. Only 13 percent were released on their own recognizance to await trial. When bail was set, the median amount was $10,000.

Since the 2019 reform went into effect, New York law has required that judges offer the option of a partially secured bond in addition to cash bail. A partially secured bond allows defendants to pay a portion of the total bail (capped at 10 percent) to go free while owing the full amount if they do not show up to court. The court watchers observed that judges followed the letter of the law while violating the spirit: Secured bonds were set much higher than the cash option, so that many defendants still faced impossible-to-meet charges.

With COVID came a shift in methods. Instead of visiting courts in person, volunteers looked up data in WebCrims, a state-run website that tracks cases. Since October 2020, the CourtWatch team has trained more than 50 digital court watchers, who have compiled data from nearly 6,000 arraignments. Tabulating data online comes with some advantages—the volunteers are no longer trying to guess the approximate age or other demographic data of the defendant. However, their absence in person may be felt by defendants and their attorneys. Those yellow shirts, in the opinion of one volunteer I spoke with, are a tangible pledge of support for inmates in a hostile environment.

The presence of court watchers can change the atmosphere of a courtroom, but the courtroom experience changes the court watchers as well. Just as body cameras changed the way people saw policing, physical presence changes the volunteers’ understanding of their government. It’s seldom that TV procedurals focus on arraignment and bail, but it’s this step of the criminal justice system that often determines the outcome.

Nationwide, only 2 percent of federal criminal defendants go to trial, according to a Pew Research Center analysis. In New York in 2017, the figure was 3 percent. Most cases are resolved through plea bargains, and defendants who are detained before trial are much more likely to plea out. When the BCBF was paying criminal bail, the group found that its clients were “three times as likely to have their criminal cases dismissed or resolved favorably compared with similarly situated individuals incarcerated pretrial on low amounts of bail.”

It was court watching, in fact, that spurred Goldberg to make bail reform his full-time job. He had been working at a white-shoe law firm, making time for pro bono projects. The Brooklyn Defenders, a well-known public defender organization, asked him for help setting up a bail fund, and as part of his research he began sitting in on arraignments. The visits galvanized him. “Once you see the system firsthand,” he says, “you can’t let it continue.” CourtWatch lets the system create its own critics.

Doing Good in a Moment of Crisis

From the earliest days of the BCBF, its work included a data-gathering component, even if it wasn’t explicitly part of the mission. The team members paying bails became experts on all the unwritten rules of the bail system. “A family member does this only once. We do this every day,” explains Ash Stephens, a senior bail associate at the fund.

The bail payers learned when to rush to post a bail before a shift change, because if they missed that unofficial deadline, the client might wind up stuck in jail overnight. They learned how the operation varied from borough to borough, which offices still relied on fax machines, which kinds of payment were accepted. They learned who to call to nag to get bail money back after a client appeared for their trial. “You have to be vigilant about it,” Stephens says.

Their experience observing the practices of for-profit bail bondsmen led the BCBF to partner with other organizations to form the Bail Bond Accountability Coalition (BBAC). They advocated for a Bail Bond Consumer Bill of Rights and other consumer protections that were eventually passed by the New York City Council in 2018. Bondsmen were required to provide potential clients with that bill of rights, which detailed maximum fee schedules, information on reclaiming collateral, and instructions for reporting a dishonest agent.

In some ways, this was the beginning of the bail fund’s incorporation into the system it wanted to dismantle. The criminal justice system is much larger than those who are officially employed by courts, prisons, and prosecutors and public defenders offices. The prison-industrial complex has delegated many jobs to private entities who aren’t directly accountable to voters.

Prisoners’ phone calls are administered by for-profit entities, for example. Their family visits are replaced by proprietary videoconferences. Even their mail is handled by a service that scans and digitizes it, eliminating the inmate’s opportunity to touch the crayon scribbles from a child or smell a partner’s perfume on the paper. In some cases, these companies provide services the prisoners would otherwise not have access to at all. But too often, they exploit what is typically a state-guaranteed monopoly over a literal captive audience to extract high fees for poor service—all with less theoretical accountability than their public sector counterparts.

Goldberg sees for-profit bail companies as part of this larger system. “We have outsourced an important function—ensuring people come to court,” he says. But defendants don’t have the same due-process protections in their interactions with private companies that they have with agents of the state. “Bondsmen can do things we don’t allow police to do,” says Goldberg—for example, entering your home without a warrant.

Technically, the defendant is the customer of the bail bondsman, but clients enter the relationship under heavy pressure. “If they’re using a bondsman, they’re in a point of absolute crisis,” Goldberg argues. People facing incarceration are no better prepared to be canny consumers than a heart attack victim trying to comparison shop hospitals from his ambulance gurney. The bondsmen become one more piece of what Goldberg calls the “user-funded criminal justice system.”

To the extent it could, the BCBF tried to use that moment of crisis as an opportunity to do good. When the fund was paying bail, it also operated a client services team that aimed to help with more than just the immediate problem of pending incarceration. “We have access to a person at a moment of maximum vulnerability,” says Benson, the group’s development director. Often, a client’s situation was already unstable; merely bailing them out leaves them at risk of repeated encounters with the legal system. “It’s a function of poverty that that person was in a position that led to arrest in the first place.”

The arrest offered the client services team a chance to intervene, but the team says it was important that they not overwhelm or dictate to clients in their moment of vulnerability. “It’s easier to say, ‘You’re homeless, go to a shelter,'” Goldberg says, “than to hear what they need.”

The client services team is staffed primarily by people who have themselves had brushes with the criminal justice system. They don’t funnel clients into a program or demand anything in exchange for paying bail.

The day prior to our 2018 interview, Derrick Cain, then the director of client services, had been supervising two relatively green interns. The client services team is supposed to respond only to a client’s self-identified needs, but when the interns sat down with the man they were supposed to help, they couldn’t contain themselves. The client entered the office in dusty, dirty clothes, and the interns were eager to show him to the clothing closet.

It wasn’t until Cain stepped in that the client had space to say he didn’t need clothes—he needed a hardhat. He was a construction worker, untroubled by the grime of the job, but he needed supplies to do his work and a MetroCard to cover his commute through the end of the week.

The clients’ culture clash begins at the front door. At the time I visited, the BCBF office was housed within a WeWork building. That company’s quirky yet sterile “airspace” aesthetic made it a strange fit for a bail fund. Décor featuring “gilded boxer dogs,” Goldberg says, hardly put clients at ease or made them feel welcome.

Cain saw it as part of his job to run interference with the WeWork staff. The week before our 2018 conversation, the lobby manager had called the police on one of the BCBF clients, one who Cain said struggled with “severe mental health issues.”

Before he left in 2020 to found Touchdown NYC, an organization that helps former inmates as they reenter society, Cain was a bridge to the office staff as well as to the clients. He preferred to avoid bringing up his own history of incarceration (24 years, second-degree murder), but there were people who come in with an ingrained distrust of organizations that claim to help. Cain had similar frustrations when he was reentering society, winding up in an employment program that he felt was focused only on getting bodies in a room to collect fees, not on providing real help. He would share his story when he thought it was necessary. “But I hate doing it,” he told me at the time.

Connecting to a client isn’t a guarantee the team can help. Some needs are simple—clients often need a cellphone so they can receive reminders about their court dates. Others need help getting an ID or finding employment opportunities. The team routinely hands out Connections, a thick paperback book published by the public library that acts as a switchboard of service organizations.

But some client-identified needs are much harder to meet. Addressing mental health issues or chemical dependency means going beyond the client services team. Housing in New York is hard to come by. Although the team can put clients in touch with navigators and advocates, “We’re not going to create the housing,” Benson says. Paying bails is more immediately solvable. “Housing isn’t a $500 dollar problem.”

‘The Cage as a Last Resort’

The shift from bail and client services to research and advocacy removes the excitement of having an impact right away. Donors who want to be part of keeping someone out of jail today can donate to other active bail funds. (BCBF donations still go to support immigration bond payments, which revolve much more slowly than ordinary bond payments and thus require a larger pool of reserves.) Those who stick with the BCBF are making an investment in an uncertain future.

Bail reform has the potential for a broad appeal. The more modestly it frames its goals, the more people may be sympathetic. It can be simply a form of better quality control—helping judges be smarter about which bail options they use, making sure the most dangerous defendants are held while letting others go free. This is the technocratic approach offered by recidivism prediction algorithms, which have come under criticism for racial disparities in their recommendations.

That’s not the tack Parker, the CourtWatch program coordinator, took when she led a seminar for CourtWatch volunteers in March 2021. Parker didn’t talk about patching the cracks of a flawed system—she positioned the program as part of the effort to begin dismantling the system. She was skeptical of incremental improvements, saying, “We don’t necessarily believe there is a progressive way to cage and torture people and separate them from their families.”

Hamad-Lipscombe knows that calling for a future without prisons is a controversial tack to take. But as he sees it, the status quo has already been proven not to work. At minimum, he wants to see an inversion of the current system, where incarceration is the default response to crime. Today, he says, “we start from a position of ‘let’s put someone in a cage and then figure out if something else could work,’ rather than seeing the cage as a last resort.”

It’s easier to point at what’s wrong with the current system than it is to offer a clear vision of an alternative. When district attorneys focus on conviction rates as a measure of their success, they imply that their goal is to achieve a guilty verdict every time. If instead the D.A. sees his or her role in the context of a truth-sifting adversarial system, it isn’t necessarily a defeat to lose a case. They make the strongest good-faith case they can in order to help the jurors weigh the evidence. Sometimes that will mean discovering that the defendant should not be convicted. It’s rare to hear a D.A. speak about cases he or she feels proud of losing.

Still, conviction rates are easy to tabulate. When I asked Hamad-Lipscombe what a better statistic would be to measure the effectiveness of a D.A., he pointed to holistic measures of the health of the community the D.A. serves. “A good goal is for communities to be safe without incarceration,” he says.

That may be the goal, but at that point the D.A.’s efforts are mingled and mixed with everyone else serving the community. The D.A. can do a good job but find it isn’t enough for a community mired in poverty. Hamad-Lipscombe’s framework reflects the fact that criminal justice can’t be neatly cleaved off from social policy, but it makes it hard to track what’s working and what’s not.

The balance is hard to strike. It takes careful, patient observation to muster evidence and prompt large-scale change. In the meantime, any individual inmate will need to turn to a different bail fund to get immediate help. When he was still with the BCBF, Cain saw his client services work as an act of resistance to the carceral system as well as a source of relief for the clients he worked with. Everywhere else, he explained, the system operated on mass principles: “You need bodies to fill up police cars; you need bodies to fill up Rikers Island.” With each personal conversation and individualized plan, Cain was testifying that the defendants he served weren’t part of an undifferentiated agglomeration.

The CourtWatch volunteers share Cain’s experience—they see the defendants pass by, individual by individual. They translate them into spreadsheets and charts, but it’s the moments of encounter that motivate them to push to change the patterns they’re tracking.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3knxRDD

via IFTTT