11/24/2001: Salim Hamdan was captured in Afghanistan. The Supreme Court would decide his case in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006).

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2UYb57y

via IFTTT

another site

11/24/2001: Salim Hamdan was captured in Afghanistan. The Supreme Court would decide his case in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006).

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2UYb57y

via IFTTT

Rio Wojtecki, a 15-year-old Florida resident, hadn’t been in trouble for nearly a year. But in late 2019, sheriff’s deputies started showing up everywhere to “check up” on him.

Over four months, deputies from the Pasco County Sheriff’s Office contacted Wojtecki or his family 21 times—at his house, at his gym, at his parents’ work. When Wojtecki’s older sisters refused to let deputies inside the house during one of their frequent late-night visits, a deputy shouted, “You’re about to have some issues.” He threatened to write the family a ticket for not having their address number appropriately posted on their mailbox.

Wojtecki was one of nearly 1,000 Pasco County residents who ended up on a list of “prolific offenders” created by the sheriff’s predictive policing program. The scope of the program, launched in 2011, was first revealed by the Tampa Bay Times in a stunning investigation published this September.

Predictive policing, or “intelligence-led policing,” is the use of algorithms and huge troves of data to analyze crime trends. Departments use predictive policing software to identify crime hot spots—but it can also be used, as in Pasco County, to create “risk scores” that supposedly identify individuals who are likely to be perpetrators or victims of crimes. While Pasco County Sheriff Chris Nocco touted the program as a futuristic tool to stop crime before it happens by keeping tabs on likely criminals, a former deputy interviewed by the Tampa Bay Times described the program’s tactics this way: “Make their lives miserable until they move or sue.”

The newspaper found eight other families who said they were threatened with or received code enforcement citations for offenses such as missing mailbox numbers and overgrown grass. Three of the targeted people had developmental disabilities. At least one family did move to a different county to escape the harassment.

During the last decade, several major cities have launched predictive policing programs, lured by the promise of an objective, high-tech method for reducing crime. But audits and research into the effectiveness of such efforts have yielded mixed to negative assessments. Chicago ended a predictive policing program in January following audits by the RAND Corp. and the city’s inspector general that revealed serious flaws. Santa Cruz, California, banned the use of such policing tools in June. Portland, Oregon, stopped using one of its predictive policing algorithms in September.

Pasco County nevertheless defends its program. In fact, Nocco plans to expand it to include people frequently committed to psychiatric hospitals under Florida’s Baker Act.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3nLhOy6

via IFTTT

Rio Wojtecki, a 15-year-old Florida resident, hadn’t been in trouble for nearly a year. But in late 2019, sheriff’s deputies started showing up everywhere to “check up” on him.

Over four months, deputies from the Pasco County Sheriff’s Office contacted Wojtecki or his family 21 times—at his house, at his gym, at his parents’ work. When Wojtecki’s older sisters refused to let deputies inside the house during one of their frequent late-night visits, a deputy shouted, “You’re about to have some issues.” He threatened to write the family a ticket for not having their address number appropriately posted on their mailbox.

Wojtecki was one of nearly 1,000 Pasco County residents who ended up on a list of “prolific offenders” created by the sheriff’s predictive policing program. The scope of the program, launched in 2011, was first revealed by the Tampa Bay Times in a stunning investigation published this September.

Predictive policing, or “intelligence-led policing,” is the use of algorithms and huge troves of data to analyze crime trends. Departments use predictive policing software to identify crime hot spots—but it can also be used, as in Pasco County, to create “risk scores” that supposedly identify individuals who are likely to be perpetrators or victims of crimes. While Pasco County Sheriff Chris Nocco touted the program as a futuristic tool to stop crime before it happens by keeping tabs on likely criminals, a former deputy interviewed by the Tampa Bay Times described the program’s tactics this way: “Make their lives miserable until they move or sue.”

The newspaper found eight other families who said they were threatened with or received code enforcement citations for offenses such as missing mailbox numbers and overgrown grass. Three of the targeted people had developmental disabilities. At least one family did move to a different county to escape the harassment.

During the last decade, several major cities have launched predictive policing programs, lured by the promise of an objective, high-tech method for reducing crime. But audits and research into the effectiveness of such efforts have yielded mixed to negative assessments. Chicago ended a predictive policing program in January following audits by the RAND Corp. and the city’s inspector general that revealed serious flaws. Santa Cruz, California, banned the use of such policing tools in June. Portland, Oregon, stopped using one of its predictive policing algorithms in September.

Pasco County nevertheless defends its program. In fact, Nocco plans to expand it to include people frequently committed to psychiatric hospitals under Florida’s Baker Act.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3nLhOy6

via IFTTT

A police officer in Cambridgeshire, England, has been accused of switching the bar code on a box of donuts and trying to buy them in the self-checkout line for seven pence (93 cents). The actual price was £9.95 (about $13). Simon Read will face a misconduct hearing and could lose his job.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3nVyumv

via IFTTT

A police officer in Cambridgeshire, England, has been accused of switching the bar code on a box of donuts and trying to buy them in the self-checkout line for seven pence (93 cents). The actual price was £9.95 (about $13). Simon Read will face a misconduct hearing and could lose his job.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3nVyumv

via IFTTT

At Verdict, Mike Dorf considers whether the state and federal governments could require people to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. He writes that the leading precedent is Jacobson v. Massachusetts (1905).

Could government mandate vaccination for people who lack valid medical reasons why a generally safe and effective vaccine would pose an unacceptably high health risk for them? A 1905 Supreme Court opinion—Jacobson v. Massachusetts—says yes.

The law at issue in Jacobson did not impose a vaccine mandate. Rather, people who refused to receive the smallpox vaccine had to pay a $5 fine. (About $150 in present-day value). And the failure to pay the fine would result in a jail sentence. But the state lacked the power to jab a syringe in the offender’s arm. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court observed, “[i]f a person should deem it important that vaccination should not be performed in his case, and the authorities should think otherwise, it is not in their power to vaccinate him by force, and the worst that could happen to him under the statute would be the payment of the penalty of $5.”

In short, the failure to comply with the mandate required the payment of a penalty. And being forced to pay a nominal fine does not invade any “fundamental right.” This model resembles the Affordable Care Act, as construed by Chief Justice Roberts’s saving construction in NFIB v. Sebelius. People are not mandated to purchase insurance; rather, those who fail to purchase insurance must pay a tax-penalty

Mike’s reading is a very, very common misreading of Jacobson. Indeed, Mike is in good company. In Buck v. Bell, Justice Holmes misread the scope of Jacobson—a decision that he joined. Justice Holmes analogized government-compelled sterilization to government-compelled vaccination. Holmes concluded that “the principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes.” But Jacobson did not actually sustain “compulsory vaccination.”

Jacobson, standing by itself, will not support a vaccine mandate. If the state or federal governments wish to forcibly vaccinate people, they will have to rely on Buck v. Bell. That anticanonical case upheld the state’s power to forcibly perform medical procedures on people to promote the public good. Roe v. Wade favorably cited Buck to support this proposition. In Roe, Justice Blackmun contended, the state retains the authority to force a woman to maintain a pregnancy for, among other reasons, to “protect[] potential life.” Justice Blackmun explained that “[t]he Court has refused to recognize an unlimited right” “to do with one’s body as one pleases.” To support this proposition, Justice Blackmun cited two cases, with one-word parentheticals: “Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11, 25 S.Ct. 358, 49 L.Ed. 643 (1905) (vaccination); Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200, 47 S.Ct. 584, 71 L.Ed. 1000 (1927) (sterilization).”

I discuss this history of Jacobson in my new article, What Rights are “Essential”? The 1st, 2nd, and 14th Amendments in the Time of Pandemic.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3m2m3F3

via IFTTT

At Verdict, Mike Dorf considers whether the state and federal governments could require people to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. He writes that the leading precedent is Jacobson v. Massachusetts (1905).

Could government mandate vaccination for people who lack valid medical reasons why a generally safe and effective vaccine would pose an unacceptably high health risk for them? A 1905 Supreme Court opinion—Jacobson v. Massachusetts—says yes.

The law at issue in Jacobson did not impose a vaccine mandate. Rather, people who refused to receive the smallpox vaccine had to pay a $5 fine. And the failure to pay the fine would result in a jail sentence. But the state lacked the power to jab a syringe in the offender’s arm. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court observed, “[i]f a person should deem it important that vaccination should not be performed in his case, and the authorities should think otherwise, it is not in their power to vaccinate him by force, and the worst that could happen to him under the statute would be the payment of the penalty of $5.”

In short, the failure to comply with the mandate required the payment of a penalty. And being forced to pay a nominal fine does not invade any “fundamental right.” This model resembles the Affordable Care Act, as construed by Chief Justice Roberts’s saving construction in NFIB v. Sebelius. People are not mandated to purchase insurance; rather, those who fail to purchase insurance must pay a tax-penalty

Mike’s reading is a very, very common misreading of Jacobson. Indeed, Mike is in good company. In Buck v. Bell, Justice Holmes misread the scope of Jacobson—a decision that he joined. Justice Holmes analogized government-compelled sterilization to government-compelled vaccination. Holmes concluded that “the principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes.” But Jacobson did not actually sustain “compulsory vaccination.”

Jacobson, standing by itself, will not support a vaccine mandate. If the state or federal governments wish to forcibly vaccinate people, they will have to rely on Buck v. Bell. That anticanonical case upheld the state’s power to forcibly perform medical procedures on people to promote the public good. Roe v. Wade favorably cited Buck to support this proposition. In Roe, Justice Blackmun contended, the state retains the authority to force a woman to maintain a pregnancy for, among other reasons, to “protect[] potential life.” Justice Blackmun explained that “[t]he Court has refused to recognize an unlimited right” “to do with one’s body as one pleases.” To support this proposition, Justice Blackmun cited two cases, with one-word parentheticals: “Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11, 25 S.Ct. 358, 49 L.Ed. 643 (1905) (vaccination); Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200, 47 S.Ct. 584, 71 L.Ed. 1000 (1927) (sterilization).”

I discuss this history of Jacobson in my new article, What Rights are “Essential”? The 1st, 2nd, and 14th Amendments in the Time of Pandemic.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3m2m3F3

via IFTTT

From People v. Underhill (Colo. Sup. Ct. Office of Presiding Disciplinary Judge, issued Sept. 17 but just posted on Westlaw recently):

The Presiding Disciplinary Judge dismissed the reinstatement petition of James C. Underhill Jr. on September 17, 2020.

In 2015, Underhill was suspended for eighteen months, to run consecutive to a suspension imposed in an earlier disciplinary case. Underhill was disciplined for publicly responding to former clients’ negative online reviews with internet postings that disclosed sensitive and confidential information obtained during the representation. Underhill then sued the couple for defamation and communicated with them ex parte, even though he knew that they were represented by counsel, and despite their lawyer’s repeated demands that he not do so. When the lawsuit was dismissed, Underhill brought a second defamation action in a different court, alleging without adequate factual basis that the couple had made other defamatory internet postings. Underhill was also suspended for misconduct in a second client matter in which he published an attorney-client communication online.

The Presiding Disciplinary Judge dismissed Underhill’s petition for reinstatement with leave to refile. The Presiding Disciplinary Judge concluded that because five years had elapsed since Underhill had been suspended, he was required under C.R.C.P. 251.29(b) to pass the Colorado bar exam before petitioning for reinstatement. Because Underhill neither took nor passed the Colorado bar exam before petitioning for reinstatement, the Presiding Disciplinary Judge found that Underhill failed to state a claim that he is entitled to be reinstated to the practice of law in Colorado.

To be fair, it’s hard for a lawyer (or a psychiatrist or someone in a similar profession) to respond to clients’ negative reviews, given the obligations of confidentiality. But that’s part of the job.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/33dU8uB

via IFTTT

From People v. Underhill (Colo. Sup. Ct. Office of Presiding Disciplinary Judge, issued Sept. 17 but just posted on Westlaw recently):

The Presiding Disciplinary Judge dismissed the reinstatement petition of James C. Underhill Jr. on September 17, 2020.

In 2015, Underhill was suspended for eighteen months, to run consecutive to a suspension imposed in an earlier disciplinary case. Underhill was disciplined for publicly responding to former clients’ negative online reviews with internet postings that disclosed sensitive and confidential information obtained during the representation. Underhill then sued the couple for defamation and communicated with them ex parte, even though he knew that they were represented by counsel, and despite their lawyer’s repeated demands that he not do so. When the lawsuit was dismissed, Underhill brought a second defamation action in a different court, alleging without adequate factual basis that the couple had made other defamatory internet postings. Underhill was also suspended for misconduct in a second client matter in which he published an attorney-client communication online.

The Presiding Disciplinary Judge dismissed Underhill’s petition for reinstatement with leave to refile. The Presiding Disciplinary Judge concluded that because five years had elapsed since Underhill had been suspended, he was required under C.R.C.P. 251.29(b) to pass the Colorado bar exam before petitioning for reinstatement. Because Underhill neither took nor passed the Colorado bar exam before petitioning for reinstatement, the Presiding Disciplinary Judge found that Underhill failed to state a claim that he is entitled to be reinstated to the practice of law in Colorado.

To be fair, it’s hard for a lawyer (or a psychiatrist or someone in a similar profession) to respond to clients’ negative reviews, given the obligations of confidentiality. But that’s part of the job.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/33dU8uB

via IFTTT

The Santa Clara County D.A.’s Office released this statement today:

County Undersheriff, Sheriff’s Captain, Local Businessman, and Apple’s Chief Security Officer Charged with Bribery for CCW Licenses

A grand jury has issued two indictments charging the Santa Clara County Undersheriff, a previously indicted sheriff’s captain, a local business owner, and the head of Global Security for Apple, Inc. with bribery.

Undersheriff Rick Sung, 48, and Captain James Jensen, 43, are accused of requesting bribes for concealed firearms (CCW) licenses, while insurance broker Harpreet Chadha, 49, and Apple’s Chief Security Officer Thomas Moyer, 50, are accused of offering bribes to get them.

The defendants will be arraigned on January 11, 2021 at the Hall of Justice in San Jose. If convicted, the defendants could receive prison time.

DA Jeff Rosen said: “Undersheriff Sung and Captain Jensen treated CCW licenses as commodities and found willing buyers. Bribe seekers should be reported to the District Attorney’s Office, not rewarded with compliance.”

The two-year investigation by the District Attorney’s Office revealed that Undersheriff Sung, aided by Captain Jensen in one instance, held up the issuance of CCW licenses, refusing to release them until the applicants gave something of value.

In the case of four CCW licenses withheld from Apple employees, Undersheriff Sung and Cpt. Jensen managed to extract from Thomas Moyer a promise that Apple would donate iPads to the Sheriff’s Office. The promised donation of 200 iPads worth close to $70,000 was scuttled at the eleventh hour just after August 2, 2019, when Sung and Moyer learned of the search warrant that the District Attorney’s Office executed at the Sheriff’s Office seizing all its CCW license records.

In the case of the CCW license withheld from Harpreet Chadha, Sung managed to extract from Chadha a promise of $6,000 worth of luxury box seat tickets to a San Jose Sharks hockey game at the SAP Center on Valentine’s Day 2019. Sheriff Laurie Smith’s family members and some of her biggest political supporters held a small celebration of her re-election as Sheriff in the suite.

The various fees required to obtain a CCW license generally total between $200 and $400. Under state law, it is a crime to carry a concealed firearm without a CCW license. Although state law requires that the applicant demonstrate “good cause” for the license, in addition to completing a firearms course and having good moral character, the sheriff has broad discretion in determining who should qualify.

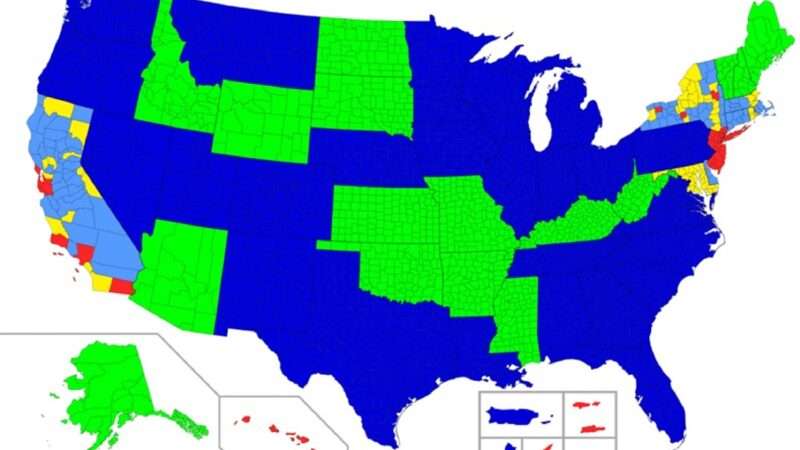

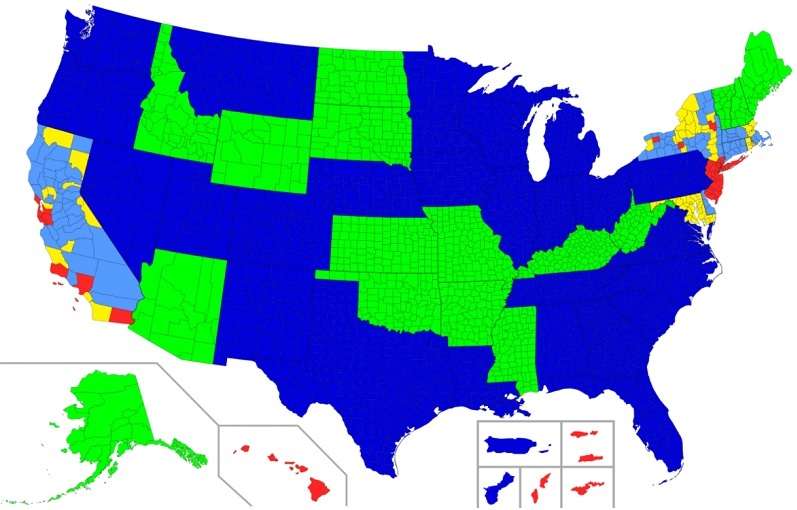

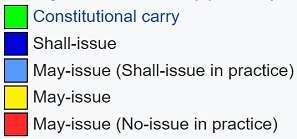

The may-issue states today are California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island (though I’ve heard mixed things on just how available permits are in Connecticut, Delaware, and Rhode Island). In 1986, this roughly 80%-20% split in favor of broad concealed carry rights was roughly 80%-20% in the opposite direction; one of the key gun control stories of the last 35 years has been the decontrol of concealed carry. Here is the Wikipedia map of the rules as of 2019, county-by-county; it seems generally right, though I can’t speak for all the details:

(“Constitutional carry” refers to concealed carry being allowed without a license; shall-issue refers to a regime where law enforcement is required to issue a license so long as the recipient is a law-abiding adult who satisfies some largely objective criteria.)

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2J2ifoT

via IFTTT