“We are turning our only home into an uninhabitable hell for millions of people,” assert the authors of “Human Cost of Disasters 2000-2019,” a new report issued on behalf of the United Nations (U.N.) Office of Disaster Risk Reduction. “This report focuses primarily on the staggering rise in climate-related disasters over the last twenty years,” the authors add. The report is based on data collected in the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) curated by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters located at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium.

The U.N. and Louvain researchers tally the toll of death and destruction from all natural disasters over the past 20 years. Between 2000 to 2019, there were 7,348 major recorded natural disaster events killing 1.23 million people with economic losses amounting to approximately $2.97 trillion. In contrast, between 1980 and 1999 there were only 4,212 natural disasters that killed 1.19 million people and resulted in $1.63 trillion in losses.

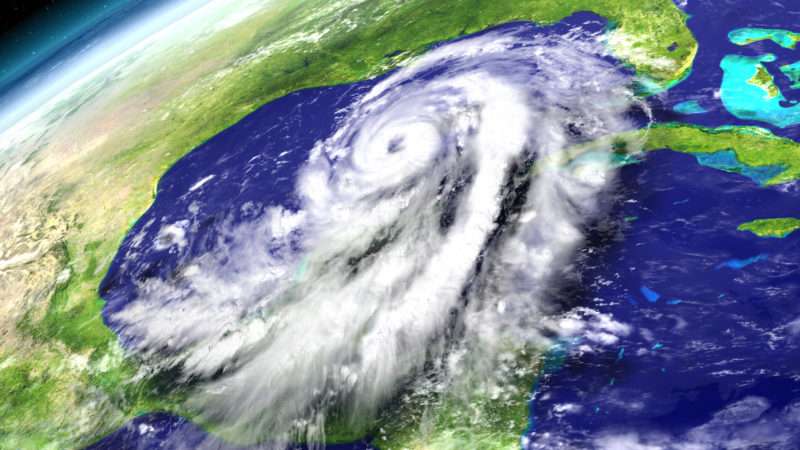

The report observes that floods and storms were by far the most prevalent events. “The last 20 years has seen the number of major floods more than double, from 1,389 to 3,254, while the incidence of storms grew from 1,457 to 2,034,” notes the accompanying press release. “This is clear evidence that in a world where the global average temperature in 2019 was 1.1 ̊C above the pre-industrial period, the impacts are being felt in the increased frequency of extreme weather events including heatwaves, droughts, flooding, winter storms, hurricanes, and wildfires,” declares the report. It is worth noting that 58 percent of disaster deaths between 2000 and 2019 were the result of earthquakes.

Let’s take a look at the evidence for how rising average global temperature specifically is affecting humanity. First, the report observes that between 2000 and 2019, there were 510,837 deaths associated with 6,681 climate-related disasters. However, the researchers note 3,656 climate-related disasters recorded between 1980 and 1999 resulted in 995,330 deaths. In other words, according to EM-DAT data, climate-related deaths in the two periods fell by nearly half while such disasters nearly doubled.

What about the upward trend in economic losses from natural disasters? According to the Human Cost report, such cumulated losses increased by 82 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars between the two 20-year periods. Interestingly, gross world product roughly grew by 82 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars between 1999 and 2019.

To get a better handle on the question of whether climate change is adding to the destruction wreaked by natural disasters, researchers seek to “normalize” the losses by attempting to estimate direct economic costs from a historical storm as if that same event were to occur under contemporary social conditions. For example, far more people live in Florida now than 50 years ago, with lots more houses and businesses, so hurricanes that strike there today are more likely to cause more significant economic losses than those than hit that state in the 1920s.

In a July 2020 article in Environmental Hazards reviewing the findings of 54 different disaster loss normalization studies, University of Colorado researcher Roger Pielke, Jr. reports, “A very strong, bottom-line conclusion across the normalisation literature is that evidence of a signal of human-caused climate change in the form of increased global economic losses from more frequent or more intense weather extremes has not yet been detected. This does not mean that such a signal does not exist, but rather, it may be too small to yet detect.”

Pielke adds, “Regrettably, scientific and public discussion of normalisation research and associated extreme weather has become deeply politicised, with opponents to climate action sometimes misusing normalisation research results to suggest human-caused climate change is not occurring. Similarly, some advocates for climate action see the results of normalisation research as a threat to an agenda that emphasizes the influence of accumulating greenhouse gases on every extreme event, with claims often going well beyond what science presently supports.”

The upshot is that humanity is losing more houses and infrastructure to bad weather largely because a richer and more populous world has put much more property in harm’s way. Once you adjust for that, the proportion of assets damaged by storms and floods possibly amplified by climate change is not yet appreciably increasing. Even better news is that as a result of rising wealth and improving technologies, fewer people over the past decades are dying from weather disasters. Pielke is right when he concludes, “Overall, improved adaptive capacity and declining vulnerability suggest optimism for our collective ability to respond to a changing and uncertain climate future.”

Perhaps the world will not become an uninhabitable hell after all.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3k2Swdp

via IFTTT