I argued last week that it was premature to condemn Sweden’s approach to COVID-19, which has been notably less restrictive than the policies adopted by other European countries and the United States. At the time, Sweden’s per capita COVID-19 death rate was slightly higher than the U.S. rate. Since then, the U.S. rate has surpassed Sweden’s, and the trajectory of deaths suggests that Sweden has been more successful at reducing mortality, despite (or perhaps because of) the government’s decision to eschew a broad lockdown.

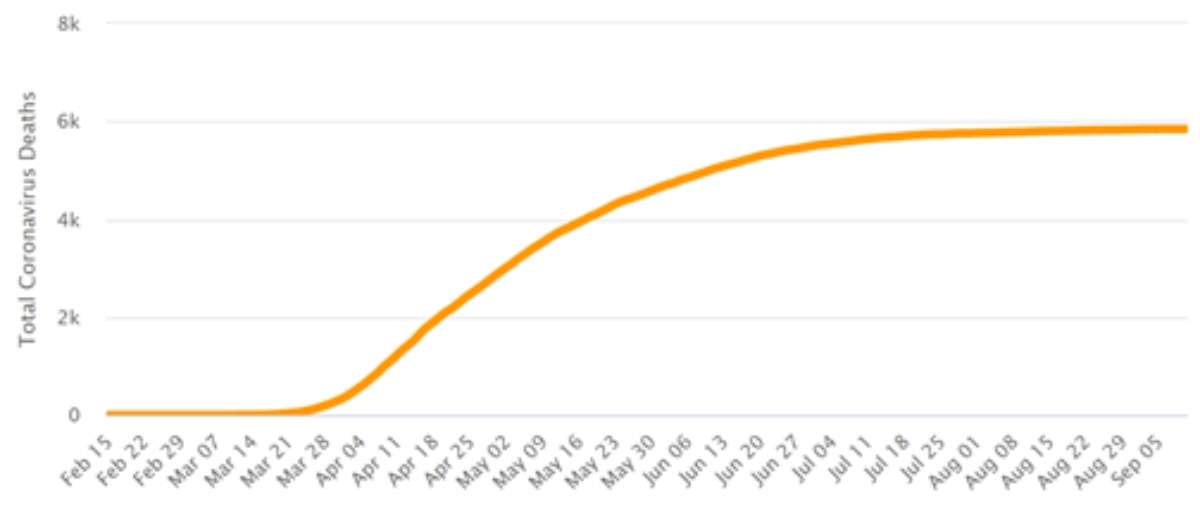

According to Worldometer’s tallies, the United States so far has seen 594 COVID-19 deaths per 1 million people, compared to 578 in Sweden. Even more strikingly, deaths in Sweden have barely risen since late June, while deaths in the United States have been climbing steadily since late March. Here is what the graph of cumulative deaths looks like for Sweden:

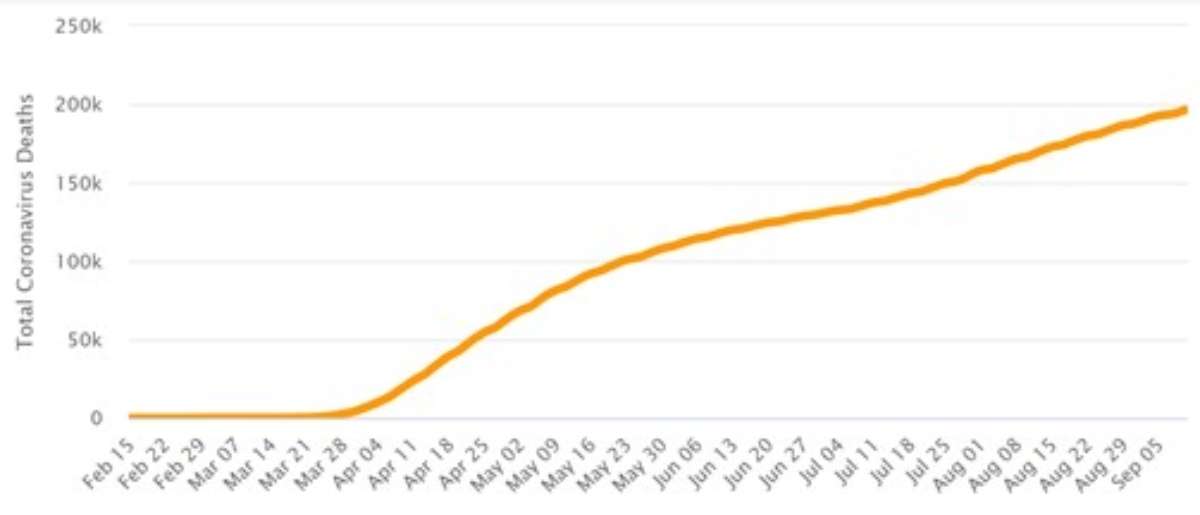

And here is what that same graph looks like for the United States:

In Sweden, the seven-day average of weekly deaths peaked at 99 on April 16. It has been in the single digits since July 17, hovering around 1 or 2 in recent days. In the United States, that average peaked at 2,256 on April 21. It dropped below 1,000 in early June but rose above that number by late July. Yesterday it was 750, which is two-thirds less than the peak but still substantial, equivalent to about 23 deaths a day in Sweden.

Newly confirmed cases are falling in both countries, but the downward trend in Sweden has been much sharper since late June. The seven-day average of daily new cases has fallen by more than 80 percent in Sweden since June 29. During the same period in the United States, that average initially rose, peaking at nearly 70,000 on July 25. It has since fallen to about 36,000, a 48 percent drop.

Despite some early blunders (most conspicuously, the failure to adequately protect nursing home residents), Sweden generally has pursued a policy that aims to protect people who are at highest risk of dying from COVID-19 while giving the rest of the population considerably more freedom than was allowed by the lockdowns that all but a few governors in the United States imposed last spring. That does not mean Swedes carried on as usual, since the government imposed some restrictions (including a ban on large public gatherings) and issued recommendations aimed at reducing virus transmission.

Achieving herd immunity was never an official goal of Sweden’s policy. But recent trends in Sweden are consistent with the hypothesis that the country has achieved some measure of herd immunity through a combination of exposure to the COVID-19 virus, T-cell response fostered by prior exposure to other coronaviruses, and greater natural resistance among the remaining uninfected population (based on the assumption that people who were most susceptible to infection were especially likely to catch the virus early in the epidemic).

In the United States, meanwhile, sweeping legal restrictions on social and economic activity, despite the enormous costs they imposed, have had no obvious impact on the upward trajectory of cumulative COVID-19 deaths. Given current trends, the gap in per capita deaths between the United States and Sweden is bound to grow, casting more doubt on the cost-effectiveness of lockdowns.

While discussion of COVID-19 tends to focus on government policy, it is important to keep in mind that many other factors, including voluntary precautions, affect the course of the epidemic. “The existing literature has concluded that NPI [nonpharmaceutical intervention] policy and social distancing have been essential to reducing the spread of COVID-19 and the number of deaths due to this deadly pandemic,” UCLA economist Andrew Atkeson and two other researchers note in a National Bureau of Economic Research paper published last month. But when Atkeson and his co-authors looked at COVID-19 trends in 23 countries and 25 U.S. states that had seen more than 1,000 deaths from the disease by late July, they found little evidence to support that conclusion.

“Early declines in the transmission rate of COVID-19 were nearly universal worldwide,” they report, which suggests that “the role of region-specific NPIs implemented in this early phase of the pandemic is likely overstated.” They note that “many of the regions in our sample that instated lockdown policies early on in their local epidemic, removed them later on in our estimation period, or have have not relied on mandated NPIs much at all.” Yet “effective reproduction numbers [the number of people infected by the average carrier] in all regions have continued to remain low relative to initial levels, indicating that the removal of lockdown policies has had little effect on transmission rates.”

Atkeson et al. argue that their findings “raise doubt about the importance [of] NPIs (lockdown policies in particular) in accounting for the evolution of COVID-19 transmission rates over time and across locations.” They suggest that other factors, such as “voluntary social distancing, the network structure of human interactions, and the nature of the disease itself,” play a more important role than variations in policy.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/33ocDf5

via IFTTT