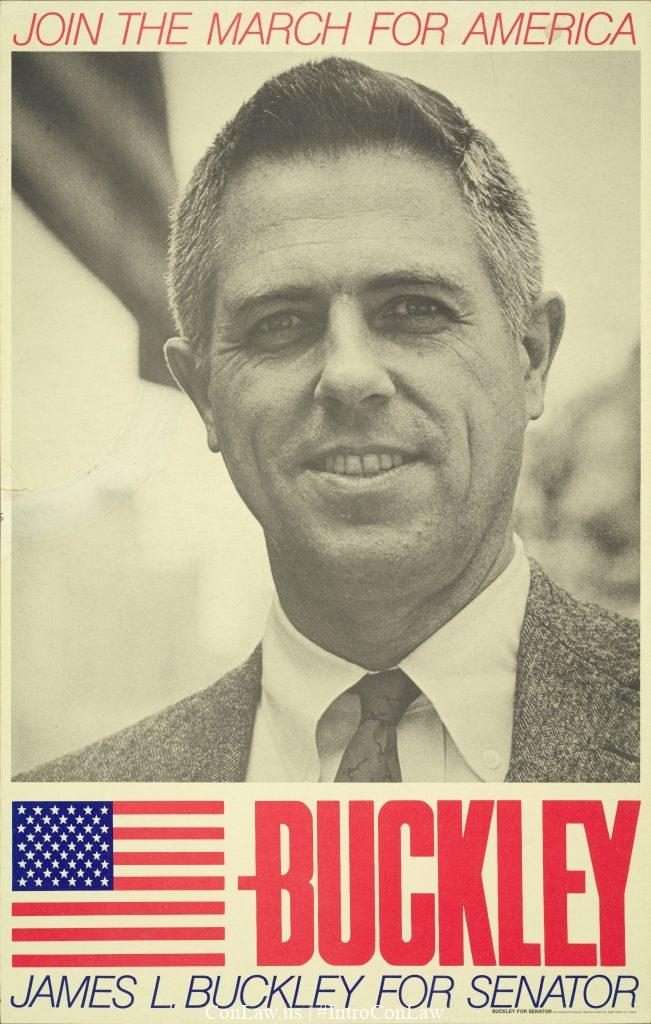

11/10/1975: Buckley v. Valeo argued.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3liRoTw

via IFTTT

another site

11/10/1975: Buckley v. Valeo argued.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3liRoTw

via IFTTT

11/10/1975: Buckley v. Valeo argued.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3liRoTw

via IFTTT

This episode’s interview with Dr. Peter Pry of the EMP Commission raises an awkward question: Is it possible that North Korea already has enough nuclear weapons to cause the deaths of hundreds of millions of Americans—by permanently frying our electrical infrastructure with a single high-altitude blast? And if he doesn’t, could the sun accomplish pretty much the same thing? The common factor in both scenarios is EMP – electro-magnetic pulse. We explore the problem in detail, from the capabilities of adversaries to the controversy that has pitted Dr. Pry and the EMP Commission against the power industry and the Energy Department, which are decidedly more confident that the US would withstand a major EMP event. And, for those disinclined to trust those sources, Dr. Pry offers a few tips on how to make it more likely that your systems will survive an EMP.

In the news, the election turned out not to be hacked, not to be violence-plagued, and not to be the subject of serious disinformation. That didn’t stop Twitter and YouTube from overreacting when a leftie hate-object, Steve Bannon, used hyperbole (“heads on pikes”) to express his unhappiness with Dr. Fauci. Really, Twitter’s Trust and Safety operation is so blinkered it can’t be fixed and should be nuked from orbit. Oh, wait, there goes my Twitter account and my YouTube career!

In legal tech news, Michael Weiner explains what’s at stake in the Justice Department’s antitrust lawsuit challenging Visa’s $5.3 billion acquisition of Plaid. I wonder if that means the Department is out of antitrust-litigating ammo. And it might be, except that you can buy a lot of ammo with $1 billion worth of Silk Road bitcoins, now being claimed by the US. Sultan Meghji says the real question is why it took the U.S. so long to lay claim to the coins.

Just when private companies have come up with plans to comply with California’s privacy law, the voters there change everything. Well, maybe not everything. It looks, Dan Podair suggests, as though compliance with the new CPRA will mostly involve complying with the old CCPA plus a whole bunch more. Meanwhile, I’m fascinated by the idea that California initiatives can say, “Oh, and by the way, this law can only be amended to make it more demanding.”

We bring Michael back to the conversation to brief us on the FTC’s plan to launch an antitrust case against Facebook using its own administrative law judges to hear the evidence. Michael admits that some might call that a kangaroo court; I suggest that LabMD’s Mike Dougherty be called as an expert witness.

Sultan and I note the ongoing failure of media and rights groups to successfully toxify facial recognition technology; now it’s been used to identify a “mostly peaceful” protestor who allegedly took a break from peacefulness to punch a cop. And it’s hard to argue with using face recognition when it confirms a picture ID the suspect left behind in Lafayette Square.

Next, Sultan and I take on Toxification II, the campaign to make people believe that racist artificial Intelligence is a thing. Poorly trained AI is definitely a thing, Sultan argues, but that doesn’t make for the same kind of story.

Charles Helleputte analyzes the latest rumor that the EU is planning to prohibit end-to-end crypto. He notes that the EU is also pursuing more infrastructure security and wonders whether the two initiatives can be sustained together.

It turns out that other people on Zoom can, in theory and under the right conditions, guess what you’re typing. It’s one more reason to be careful about webcams and security. I make the sort of cheap Jeffrey Toobin joke you’ve come to expect from me.

And more.

Download the 337th Episode (mp3)

Music by Weissman Sound Design. You can subscribe to The Cyberlaw Podcast using iTunes, Google Play, Spotify, Pocket Casts, or our RSS feed. As always, The Cyberlaw Podcast is open to feedback. Be sure to engage with @stewartbaker on Twitter. Send your questions, comments, and suggestions for topics or interviewees to CyberlawPodcast@steptoe.com. Remember: If your suggested guest appears on the show, we will send you a highly coveted Cyberlaw Podcast mug!

The views expressed in this podcast are those of the speakers and do not reflect the opinions of their institutions, clients, friends, families, or pets.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/36nE0ra

via IFTTT

This episode’s interview with Dr. Peter Pry of the EMP Commission raises an awkward question: Is it possible that North Korea already has enough nuclear weapons to cause the deaths of hundreds of millions of Americans—by permanently frying our electrical infrastructure with a single high-altitude blast? And if he doesn’t, could the sun accomplish pretty much the same thing? The common factor in both scenarios is EMP – electro-magnetic pulse. We explore the problem in detail, from the capabilities of adversaries to the controversy that has pitted Dr. Pry and the EMP Commission against the power industry and the Energy Department, which are decidedly more confident that the US would withstand a major EMP event. And, for those disinclined to trust those sources, Dr. Pry offers a few tips on how to make it more likely that your systems will survive an EMP.

In the news, the election turned out not to be hacked, not to be violence-plagued, and not to be the subject of serious disinformation. That didn’t stop Twitter and YouTube from overreacting when a leftie hate-object, Steve Bannon, used hyperbole (“heads on pikes”) to express his unhappiness with Dr. Fauci. Really, Twitter’s Trust and Safety operation is so blinkered it can’t be fixed and should be nuked from orbit. Oh, wait, there goes my Twitter account and my YouTube career!

In legal tech news, Michael Weiner explains what’s at stake in the Justice Department’s antitrust lawsuit challenging Visa’s $5.3 billion acquisition of Plaid. I wonder if that means the Department is out of antitrust-litigating ammo. And it might be, except that you can buy a lot of ammo with $1 billion worth of Silk Road bitcoins, now being claimed by the US. Sultan Meghji says the real question is why it took the U.S. so long to lay claim to the coins.

Just when private companies have come up with plans to comply with California’s privacy law, the voters there change everything. Well, maybe not everything. It looks, Dan Podair suggests, as though compliance with the new CPRA will mostly involve complying with the old CCPA plus a whole bunch more. Meanwhile, I’m fascinated by the idea that California initiatives can say, “Oh, and by the way, this law can only be amended to make it more demanding.”

We bring Michael back to the conversation to brief us on the FTC’s plan to launch an antitrust case against Facebook using its own administrative law judges to hear the evidence. Michael admits that some might call that a kangaroo court; I suggest that LabMD’s Mike Dougherty be called as an expert witness.

Sultan and I note the ongoing failure of media and rights groups to successfully toxify facial recognition technology; now it’s been used to identify a “mostly peaceful” protestor who allegedly took a break from peacefulness to punch a cop. And it’s hard to argue with using face recognition when it confirms a picture ID the suspect left behind in Lafayette Square.

Next, Sultan and I take on Toxification II, the campaign to make people believe that racist artificial Intelligence is a thing. Poorly trained AI is definitely a thing, Sultan argues, but that doesn’t make for the same kind of story.

Charles Helleputte analyzes the latest rumor that the EU is planning to prohibit end-to-end crypto. He notes that the EU is also pursuing more infrastructure security and wonders whether the two initiatives can be sustained together.

It turns out that other people on Zoom can, in theory and under the right conditions, guess what you’re typing. It’s one more reason to be careful about webcams and security. I make the sort of cheap Jeffrey Toobin joke you’ve come to expect from me.

And more.

Download the 337th Episode (mp3)

Music by Weissman Sound Design. You can subscribe to The Cyberlaw Podcast using iTunes, Google Play, Spotify, Pocket Casts, or our RSS feed. As always, The Cyberlaw Podcast is open to feedback. Be sure to engage with @stewartbaker on Twitter. Send your questions, comments, and suggestions for topics or interviewees to CyberlawPodcast@steptoe.com. Remember: If your suggested guest appears on the show, we will send you a highly coveted Cyberlaw Podcast mug!

The views expressed in this podcast are those of the speakers and do not reflect the opinions of their institutions, clients, friends, families, or pets.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/36nE0ra

via IFTTT

Dorothy Day’s first jail stint, in 1917, was a brutal experience arising from a protest for women’s suffrage. Behind bars she embarked on a hunger strike and came to know the misery of forced feeding. Women eventually got the vote. But Day, an anarchist, never cast a ballot in her life.

She would go on to become a radical icon, famous for her work with the poor and her protests against racism, nuclear weapons, and war. A socially conservative Catholic, Day frowned on the casual sex rampant among her acolytes in the ’60s. Yet she had ended her first pregnancy with an abortion and her only marriage by divorce. A hard-drinking libertine in her youth, she is today under consideration for sainthood.

Day bowed meekly to the authority of the Catholic Church but regularly ruffled its finery. A lifelong friend of the downtrodden, she took a dim view of government programs on their behalf, feeling that they harmfully relieve us of our sacred responsibilities for ourselves and one another. A leading scholar of the Church, David J. O’Brien, has called her “the most significant, interesting, and influential person in the history of American Catholicism.”

The enigmatic founder of the Catholic Worker Movement (and The Catholic Worker, the radical newspaper that sustained it) is having a moment. This November marks the 40th anniversary of her death at 83. And this spring she was the subject of two important new works: a powerful documentary and a deeply researched biography of surpassing insight and sensitivity.

Together these works reveal an extraordinary avatar of nonviolent dissent. Her popular resurrection is particularly welcome at a time when left and right seem bent on contorting themselves into mirror images of one another and a pall of orthodoxy increasingly stifles free expression. But her experience—at her chaotic Catholic Worker hospitality house, for instance—also demonstrates the limitations of anarchism, just as the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone has done in our own time.

Day’s politics are hard to pigeonhole. A lifelong pacifist, union supporter, and civil libertarian, she would seem to fit easily among such icons of the left as David Dellinger and César Chávez, who were indeed her friends. But Day was more complicated than that. While she supported a minimum wage and a 40-hour workweek, she criticized much of the New Deal and opposed Social Security. She thought government handouts bred corruption, complacency, even a love of luxury. And she condemned the “tremendous failure of man’s sense of responsibility for what he is doing. You relinquish it to the state. He’s not obedient to his own promptings of conscience.”

Therein lies the key to Day’s worldview. Although she was an avowed anarchist, the religion scholar June E. O’Connor reminded us, “she preferred the words libertarian, decentralist, and personalist.”

It was Day’s personalist outlook in particular that made her “as skeptical of many of the tenets of modern liberalism as she was of political conservatism,” write John Loughery and Blythe Randolph in their new biography, Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century (Simon & Schuster).

Not much invoked lately, personalism has been seriously underrated as an influence on American cultural and political life. Leaving undisturbed its tangled philosophical roots, the version of interest here insists on the inviolable value and dignity of the person, whose fulfillment is necessarily communal.

The historian James J. Farrell identifies personalism with the spirit of the ’60s but situates it firmly in the mainstream of the American intellectual tradition. Personalism, he says, is wary of systems, including both the market economy and the state. It also gives a special role to the poor and marginalized, who form the yardstick against which a society’s worth can be measured.

Personalists believe you can change the world by changing yourself, but also that we are morally responsible for one another. People ought to be self-governing, sincere, determined to harmonize means and ends, and bent not just on personal conversion but on shaping law, policy, and institutions, all of which in turn shape people.

“The personalism of the 1960s,” Farrell writes in his 1997 book The Spirit of the Sixties, “was a combination of Catholic social thought, communitarian anarchism, radical pacifism, and humanistic psychology.”

And it explains a lot. Day’s activism looks a lot more cohesive when you see it as an energetic and imaginative personalist enterprise that calls for a “revolution of the heart.” She promulgated a broad critique of American materialism, militarism, racism, and other ills. But again and again she emphasized personal responsibility, insisting that the Catholic faith required individual adherents to take action against injustice. Becoming too dependent on “Holy Mother State,” as she called it, would curtail our freedom, undermine our religious obligation to one another, widen the gulf between helper and helped—and often fail to solve the problem.

“She wasn’t, as people might think, a religious leftist,” the theologian and activist Jim Wallis tells filmmaker Martin Doblmeier in the new documentary Revolution of the Heart. “Dorothy on theological matters, ecclesial matters, biblical matters, was quite conservative. And she was radical in her social, economic, political views because of her conservative faith.”

Day’s intense personalism was evident in her suspicion of hierarchy, bureaucracy, and far-off authorities. “She was an anarchist in the sense that she believed that too much of our obligation toward other people, toward one another, was being taken over by the state,” the Jesuit priest Mark Massa says in the film. “And she was deeply distrustful and suspicious of what kind of world that was going to create.”

But she didn’t like capitalism either. What she liked—what she exalted—was the dignity and moral autonomy of the individual as derived from God. Always swimming against the tide, she made the journey from collectivism to Catholicism at about the same time most American reform movements were becoming ever more secular.

Day and many of her fellow 20th century personalists shunned violence. It’s noteworthy that Martin Luther King Jr. studied at Boston University, the center of American personalism. He acknowledged the doctrine’s strong influence on his thinking.

Day took pacifism seriously. In 1940, she testified before Congress against a proposal for the nation’s first peacetime draft. She opposed American involvement in World War II even after Pearl Harbor, a stance that crushed her newspaper’s circulation and bitterly divided her movement—but from which she never deviated. She was an early advocate for European Jews in their peril and an outspoken opponent of Japanese-American internment. She condemned war bonds and other sources of profit from the conflict, proclaimed (when women’s conscription was rumored) that she would never cooperate in any way, and allowed a Catholic anti-war group to urge draft resistance in The Catholic Worker, an episode that brought ecclesiastical reproach (leading to Day’s submission). After Hiroshima, she bitterly condemned America’s use of atomic weapons.

Later she became an opponent of the Vietnam War, inspiring among others the Berrigan brothers, two Catholic priests whose militant activism included the seizure and public burning of a selective service office’s draft files. It’s not too much to say that Dorothy Day made pacifism, once the province of Protestants, available to American Catholics as well. She also regularly declined to pay federal taxes, lest the money fund weapons.

Yet it would be wrong to conclude that she spent all her time in a fury of political recrimination or that she regarded America as irredeemable. She was exhausted at times by the magnitude of her undertaking at the Catholic Worker Movement, yet she exuded a characteristically American optimism. Her personalist outlook gave her faith that people can arrange their own lives and make the world better without intervention from coercive authorities.

Like so much else about Day, this faith was at least partly rooted in her Catholicism, which she came to as a young woman by means of conversion. But it may also owe something to her “lived experience,” in the redundant parlance of our times. That experience included an abusive boyfriend, cruelty behind bars, and surveillance by the FBI, whose dossier on her spanned 30 years. But Day’s life, spent mostly in service to others, was by any standard a glorious adventure.

In contrast with today’s diligent résumé-builders, she found college so wanting that she never graduated. Instead, she labored at newspapers and magazines in New York, Chicago, New Orleans, and elsewhere. She also worked at a printer’s shop, at a public library, at a department store, at a restaurant, and as an artist’s model. She never had much money, but people helped her and she, in turn, helped them.

In 1975, Robert Ellsberg, whose father Daniel was then famous for leaking the Pentagon Papers, left Harvard for a brief stint that would turn into five years at The Catholic Worker. “Being fresh out of school,” he says in Revolution of the Heart, “the only question that occurred to me was, how do you reconcile Catholicism and anarchism? And she just kind of looked at me and said, ‘It’s never been a problem for me.'”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2JQfqHH

via IFTTT

Dorothy Day’s first jail stint, in 1917, was a brutal experience arising from a protest for women’s suffrage. Behind bars she embarked on a hunger strike and came to know the misery of forced feeding. Women eventually got the vote. But Day, an anarchist, never cast a ballot in her life.

She would go on to become a radical icon, famous for her work with the poor and her protests against racism, nuclear weapons, and war. A socially conservative Catholic, Day frowned on the casual sex rampant among her acolytes in the ’60s. Yet she had ended her first pregnancy with an abortion and her only marriage by divorce. A hard-drinking libertine in her youth, she is today under consideration for sainthood.

Day bowed meekly to the authority of the Catholic Church but regularly ruffled its finery. A lifelong friend of the downtrodden, she took a dim view of government programs on their behalf, feeling that they harmfully relieve us of our sacred responsibilities for ourselves and one another. A leading scholar of the Church, David J. O’Brien, has called her “the most significant, interesting, and influential person in the history of American Catholicism.”

The enigmatic founder of the Catholic Worker Movement (and The Catholic Worker, the radical newspaper that sustained it) is having a moment. This November marks the 40th anniversary of her death at 83. And this spring she was the subject of two important new works: a powerful documentary and a deeply researched biography of surpassing insight and sensitivity.

Together these works reveal an extraordinary avatar of nonviolent dissent. Her popular resurrection is particularly welcome at a time when left and right seem bent on contorting themselves into mirror images of one another and a pall of orthodoxy increasingly stifles free expression. But her experience—at her chaotic Catholic Worker hospitality house, for instance—also demonstrates the limitations of anarchism, just as the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone has done in our own time.

Day’s politics are hard to pigeonhole. A lifelong pacifist, union supporter, and civil libertarian, she would seem to fit easily among such icons of the left as David Dellinger and César Chávez, who were indeed her friends. But Day was more complicated than that. While she supported a minimum wage and a 40-hour workweek, she criticized much of the New Deal and opposed Social Security. She thought government handouts bred corruption, complacency, even a love of luxury. And she condemned the “tremendous failure of man’s sense of responsibility for what he is doing. You relinquish it to the state. He’s not obedient to his own promptings of conscience.”

Therein lies the key to Day’s worldview. Although she was an avowed anarchist, the religion scholar June E. O’Connor reminded us, “she preferred the words libertarian, decentralist, and personalist.”

It was Day’s personalist outlook in particular that made her “as skeptical of many of the tenets of modern liberalism as she was of political conservatism,” write John Loughery and Blythe Randolph in their new biography, Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century (Simon & Schuster).

Not much invoked lately, personalism has been seriously underrated as an influence on American cultural and political life. Leaving undisturbed its tangled philosophical roots, the version of interest here insists on the inviolable value and dignity of the person, whose fulfillment is necessarily communal.

The historian James J. Farrell identifies personalism with the spirit of the ’60s but situates it firmly in the mainstream of the American intellectual tradition. Personalism, he says, is wary of systems, including both the market economy and the state. It also gives a special role to the poor and marginalized, who form the yardstick against which a society’s worth can be measured.

Personalists believe you can change the world by changing yourself, but also that we are morally responsible for one another. People ought to be self-governing, sincere, determined to harmonize means and ends, and bent not just on personal conversion but on shaping law, policy, and institutions, all of which in turn shape people.

“The personalism of the 1960s,” Farrell writes in his 1997 book The Spirit of the Sixties, “was a combination of Catholic social thought, communitarian anarchism, radical pacifism, and humanistic psychology.”

And it explains a lot. Day’s activism looks a lot more cohesive when you see it as an energetic and imaginative personalist enterprise that calls for a “revolution of the heart.” She promulgated a broad critique of American materialism, militarism, racism, and other ills. But again and again she emphasized personal responsibility, insisting that the Catholic faith required individual adherents to take action against injustice. Becoming too dependent on “Holy Mother State,” as she called it, would curtail our freedom, undermine our religious obligation to one another, widen the gulf between helper and helped—and often fail to solve the problem.

“She wasn’t, as people might think, a religious leftist,” the theologian and activist Jim Wallis tells filmmaker Martin Doblmeier in the new documentary Revolution of the Heart. “Dorothy on theological matters, ecclesial matters, biblical matters, was quite conservative. And she was radical in her social, economic, political views because of her conservative faith.”

Day’s intense personalism was evident in her suspicion of hierarchy, bureaucracy, and far-off authorities. “She was an anarchist in the sense that she believed that too much of our obligation toward other people, toward one another, was being taken over by the state,” the Jesuit priest Mark Massa says in the film. “And she was deeply distrustful and suspicious of what kind of world that was going to create.”

But she didn’t like capitalism either. What she liked—what she exalted—was the dignity and moral autonomy of the individual as derived from God. Always swimming against the tide, she made the journey from collectivism to Catholicism at about the same time most American reform movements were becoming ever more secular.

Day and many of her fellow 20th century personalists shunned violence. It’s noteworthy that Martin Luther King Jr. studied at Boston University, the center of American personalism. He acknowledged the doctrine’s strong influence on his thinking.

Day took pacifism seriously. In 1940, she testified before Congress against a proposal for the nation’s first peacetime draft. She opposed American involvement in World War II even after Pearl Harbor, a stance that crushed her newspaper’s circulation and bitterly divided her movement—but from which she never deviated. She was an early advocate for European Jews in their peril and an outspoken opponent of Japanese-American internment. She condemned war bonds and other sources of profit from the conflict, proclaimed (when women’s conscription was rumored) that she would never cooperate in any way, and allowed a Catholic anti-war group to urge draft resistance in The Catholic Worker, an episode that brought ecclesiastical reproach (leading to Day’s submission). After Hiroshima, she bitterly condemned America’s use of atomic weapons.

Later she became an opponent of the Vietnam War, inspiring among others the Berrigan brothers, two Catholic priests whose militant activism included the seizure and public burning of a selective service office’s draft files. It’s not too much to say that Dorothy Day made pacifism, once the province of Protestants, available to American Catholics as well. She also regularly declined to pay federal taxes, lest the money fund weapons.

Yet it would be wrong to conclude that she spent all her time in a fury of political recrimination or that she regarded America as irredeemable. She was exhausted at times by the magnitude of her undertaking at the Catholic Worker Movement, yet she exuded a characteristically American optimism. Her personalist outlook gave her faith that people can arrange their own lives and make the world better without intervention from coercive authorities.

Like so much else about Day, this faith was at least partly rooted in her Catholicism, which she came to as a young woman by means of conversion. But it may also owe something to her “lived experience,” in the redundant parlance of our times. That experience included an abusive boyfriend, cruelty behind bars, and surveillance by the FBI, whose dossier on her spanned 30 years. But Day’s life, spent mostly in service to others, was by any standard a glorious adventure.

In contrast with today’s diligent résumé-builders, she found college so wanting that she never graduated. Instead, she labored at newspapers and magazines in New York, Chicago, New Orleans, and elsewhere. She also worked at a printer’s shop, at a public library, at a department store, at a restaurant, and as an artist’s model. She never had much money, but people helped her and she, in turn, helped them.

In 1975, Robert Ellsberg, whose father Daniel was then famous for leaking the Pentagon Papers, left Harvard for a brief stint that would turn into five years at The Catholic Worker. “Being fresh out of school,” he says in Revolution of the Heart, “the only question that occurred to me was, how do you reconcile Catholicism and anarchism? And she just kind of looked at me and said, ‘It’s never been a problem for me.'”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2JQfqHH

via IFTTT

New York Police Department Deputy Inspector James Francis Kobel, commanding officer of its Office of Equal Employment and Opportunity, has been relieved of command after being connected to a series of posts on a law enforcement message board that officials deemed anti-Semitic, homophobic and racist. A user of the Law Enforcement Rant board called “Clouseau” reportedly used racial slurs to refer to two NYPD officers of color and referred to the city’s Hasidic Jewish community using stereotypes, among other slurs. Officials say information in Clouseau’s posts match Kobel’s biography, including his rank and when he joined the department, past assignments, where his in-laws live and the number of parishioners of his church who died in the 9/11 attack.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/38tD8Uo

via IFTTT

New York Police Department Deputy Inspector James Francis Kobel, commanding officer of its Office of Equal Employment and Opportunity, has been relieved of command after being connected to a series of posts on a law enforcement message board that officials deemed anti-Semitic, homophobic and racist. A user of the Law Enforcement Rant board called “Clouseau” reportedly used racial slurs to refer to two NYPD officers of color and referred to the city’s Hasidic Jewish community using stereotypes, among other slurs. Officials say information in Clouseau’s posts match Kobel’s biography, including his rank and when he joined the department, past assignments, where his in-laws live and the number of parishioners of his church who died in the 9/11 attack.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/38tD8Uo

via IFTTT

In the Author’s Note to my second book, Unraveled (2016), I wrote “By fate or design, my young career has tracked the trajectory of the Affordable Care Act.” Four years later, that trajectory has stayed the course. Since I graduated law school in 2009, and started teaching in 2012, debates about the legality of Obamacare have persisted. Indeed, I am now working on a third book to complete the ACA trilogy. Yet, California v. Texas is different. After nearly a decade, the law has woven itself into the fabric of our polity. Most of the staunchest critics of the law have abandoned any efforts to “repeal and replace” the statute. Now, reforms take the ACA’s planks as a starting point.

California v. Texas will signal the high-water mark of Obamacare litigation. Not a single Republican member of Congress filed an amicus brief in support of the challenge. Virtually every conservative rejects the notion that the Supreme Court should declare the ACA unconstitutional in its entirety. Perhaps these politicians are persuaded by the legal arguments in defense of the law’s constitutionality. I’m not so convinced that legal niceties made the difference. Partisans routinely accept frivolous legal arguments that achieve their policy goal. Rather, I think these politicians recognize the disaster that would result if the Supreme Court were to set aside the ACA. There is a fascinating backstory about the role Texas has played to litigate this case, alongside the federal government. The process was messy. (Stay tuned for the trilogy).

This lack of institutional support doomed the case from the outset. There was no way an argument would move from “off the wall” to “on the wall” if conservatives and liberals alike opposed it. Again, for most non-lawyers, the merits of the argument are secondary. I don’t mean that observation as a pejorative. Rather, this dynamic simply describes how legal arguments are used, or are not used by the general public. Most nonlawyers lack the capacity to assess the strength of a legal argument. Instead, they will primarily look to whether that legal argument supports their policy preferences. Or, they may look to whether people they respect advocate, or criticize that position. I’ve learned this lesson well after nearly a decade of speaking to the press. My “fan mail” looks very different depending on whether my answers tilt left or tilt right.

That history brings me to the oral arguments in California v. Texas. Both the district court and the Fifth Circuit relied heavily on my work. But I’ve received few plaudits. My position in this case has been an outlier. Scholars on the left and the right have unified. I respect the views of others, including several VC co-bloggers, who have thoughtfully responded to my position. As a general matter, I am not concerned that my views are not widely held. At this point in my career, I am quite used to this status.

Still, I look forward to the argument with some trepidation. No, not because I may be criticized. Those barbs no longer have any effect on me. Rather, I may learn that my longstanding view of NFIB may be wrong. For nearly eight years, I have firmly held an understanding about the holding in NFIB. This view was built on thousands of hours of research, which included interviews with the principal attorneys on both sides of the case. I know so much about how NFIB was litigated that I can’t view California v. Texas in a vacuum. Moreover, I have taught this understanding to thousands of students, and have written books, articles, and Op-Eds about it. I have always viewed this latest challenge differently from others, because I have always viewed the original challenge differently from others. I’ve stopped trying to explain this history to others, because lines have been firmly drawn.

Maybe my position is right. If so, then my amicus brief would provide the Court with a helpful approach to resolve the dispute. If I’m wrong, then my brief will not be helpful. Truthfully, the only person who can broker that tie is Chief Justice Roberts. And let’s be frank. No one really knows what Roberts meant–perhaps not even himself. If you think you know what Roberts really intended, check yourself. NFIB was crafted during a very tumultuous time, when attention to detail was not always possible. It’s possible we all misread the Chief. It wouldn’t be the first time. At this juncture, I approach the case with enough humility to admit that I may be wrong. I hope others will as well.

It’s possible that the Chief will not show his hand during argument. In King v. Burwell, he only asked a few questions. I suspect he may do the same in California v. Texas. And there are so many off-ramps for the Court to punt on this case, that we may never, ever learn how the Chief truly understands his opinion. It is also possible that five other members of the Court decide to write separately and reinterpret, or even deviate from NFIB. Still NFIB would be the riddle of the sphinx.

I will be listening carefully to the arguments, and hope to provide commentary in due course.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3nmrgYP

via IFTTT

In the Author’s Note to my second book, Unraveled (2016), I wrote “By fate or design, my young career has tracked the trajectory of the Affordable Care Act.” Four years later, that trajectory has stayed the course. Since I graduated law school in 2009, and started teaching in 2012, debates about the legality of Obamacare have persisted. Indeed, I am now working on a third book to complete the ACA trilogy. Yet, California v. Texas is different. After nearly a decade, the law has woven itself into the fabric of our polity. Most of the staunchest critics of the law have abandoned any efforts to “repeal and replace” the statute. Now, reforms take the ACA’s planks as a starting point.

California v. Texas will signal the high-water mark of Obamacare litigation. Not a single Republican member of Congress filed an amicus brief in support of the challenge. Virtually every conservative rejects the notion that the Supreme Court should declare the ACA unconstitutional in its entirety. Perhaps these politicians are persuaded by the legal arguments in defense of the law’s constitutionality. I’m not so convinced that legal niceties made the difference. Partisans routinely accept frivolous legal arguments that achieve their policy goal. Rather, I think these politicians recognize the disaster that would result if the Supreme Court were to set aside the ACA. There is a fascinating backstory about the role Texas has played to litigate this case, alongside the federal government. The process was messy. (Stay tuned for the trilogy).

This lack of institutional support doomed the case from the outset. There was no way an argument would move from “off the wall” to “on the wall” if conservatives and liberals alike opposed it. Again, for most non-lawyers, the merits of the argument are secondary. I don’t mean that observation as a pejorative. Rather, this dynamic simply describes how legal arguments are used, or are not used by the general public. Most nonlawyers lack the capacity to assess the strength of a legal argument. Instead, they will primarily look to whether that legal argument supports their policy preferences. Or, they may look to whether people they respect advocate, or criticize that position. I’ve learned this lesson well after nearly a decade of speaking to the press. My “fan mail” looks very different depending on whether my answers tilt left or tilt right.

That history brings me to the oral arguments in California v. Texas. Both the district court and the Fifth Circuit relied heavily on my work. But I’ve received few plaudits. My position in this case has been an outlier. Scholars on the left and the right have unified. I respect the views of others, including several VC co-bloggers, who have thoughtfully responded to my position. As a general matter, I am not concerned that my views are not widely held. At this point in my career, I am quite used to this status.

Still, I look forward to the argument with some trepidation. No, not because I may be criticized. Those barbs no longer have any effect on me. Rather, I may learn that my longstanding view of NFIB may be wrong. For nearly eight years, I have firmly held an understanding about the holding in NFIB. This view was built on thousands of hours of research, which included interviews with the principal attorneys on both sides of the case. I know so much about how NFIB was litigated that I can’t view California v. Texas in a vacuum. Moreover, I have taught this understanding to thousands of students, and have written books, articles, and Op-Eds about it. I have always viewed this latest challenge differently from others, because I have always viewed the original challenge differently from others. I’ve stopped trying to explain this history to others, because lines have been firmly drawn.

Maybe my position is right. If so, then my amicus brief would provide the Court with a helpful approach to resolve the dispute. If I’m wrong, then my brief will not be helpful. Truthfully, the only person who can broker that tie is Chief Justice Roberts. And let’s be frank. No one really knows what Roberts meant–perhaps not even himself. If you think you know what Roberts really intended, check yourself. NFIB was crafted during a very tumultuous time, when attention to detail was not always possible. It’s possible we all misread the Chief. It wouldn’t be the first time. At this juncture, I approach the case with enough humility to admit that I may be wrong. I hope others will as well.

It’s possible that the Chief will not show his hand during argument. In King v. Burwell, he only asked a few questions. I suspect he may do the same in California v. Texas. And there are so many off-ramps for the Court to punt on this case, that we may never, ever learn how the Chief truly understands his opinion. It is also possible that five other members of the Court decide to write separately and reinterpret, or even deviate from NFIB. Still NFIB would be the riddle of the sphinx.

I will be listening carefully to the arguments, and hope to provide commentary in due course.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3nmrgYP

via IFTTT