The “we vape, we vote” crowd seems to have gotten through to the White House. In the wake of a well-attended protest on the National Mall and other advocacy efforts, President Donald Trump is apparently rethinking a promised federal ban on flavored nicotine vaping products

Regulators had cleared the ban, and an announcement was expected. “One last thing was needed: Trump’s sign-off,” reports The Washington Post. “But on Nov. 4, the night before a planned morning news conference, the president balked.”

The New York Times is framing this as Trump caving to “lobbyists” at the expense of children, because its editors have never encountered a destructive moral panic they didn’t want to exacerbate.

But this is very good news for all the adults who enjoy nicotine vaping products in flavors other than tobacco, the countless former cigarette smokers who used these products to quit, and, yes, even The Children too. For those who do still find ways to inhale something they shouldn’t—and of course some will, as some teenagers always do—it’s profoundly less dangerous for them to be sneaking a mango Juul pod or some other known-source and ostensibly accountable brand and not whatever crazy crap a black-market, random-origin nicotine vaping products may contain.

The vaping-linked illnesses everyone’s been panicking are a result of synthetic vitamin E filler (and maybe other substances) that people were inhaling from mostly black-market THC vape pens. So dialing back plans to drive more nicotine vapers to the black market is not only a good political move; it’s the most prudent way to protect public health.

FREE MINDS

Can an old drug warrior learn new tricks? Democratic presidential candidates such as Sen. Kamala Harris (D–N.Y.) and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg have tried, with the former now denouncing cannabis criminalization and the latter now claiming that he regrets his city’s stop-and-frisk policies.

But another 2020 candidate—former Vice President Joe Biden—can’t seem to let go of his old tough-on-crime talking points and Drug War propaganda. He’s still opposed to the idea that marijuana should be legal across the country because it could be a “gateway drug.”

“The truth of the matter is, there’s not nearly been enough evidence that has been acquired as to whether or not it is a gateway drug,” Biden told a townhall crowd in Las Vegas on Saturday. “It’s a debate, and I want a lot more before I legalize it nationally. I want to make sure we know a lot more about the science behind it.”

This is, of course, silly. As Ellen Cranley at Business Insider points out, serious researchers

have found no solid evidence to support the claim that using marijuana leads to the use of harder drugs. A 1999 Institute of Medicine report said marijuana “typically precedes rather than follows initiation of other illicit drug use” but “does not appear to be a gateway drug to the extent that it is the cause or even that it is the most significant predictor of serious drug abuse; that is, care must be taken not to attribute cause to association.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse says research shows “the majority of people who use marijuana do not go on to use other, ‘harder’ substances,” and drug use can be affected by numerous other biological and environmental factors.

Biden did say that individual states “should be able to make a judgment to legalize marijuana” and that mere possession “should not be a crime.”

QUICK HITS

- What were people freaking out about over the weekend? British Prince Andrew giving an interview about his friendship with Jeffrey Epstein; Trump making an unscheduled visit to Walter Reed Medical Center (“phase one of my yearly physical,” he claimed); and Pete Buttigieg continuing to surge in Iowa.

Per @ForecasterEnten, this seems pretty significant in Iowa. 38% of Democratic caucus-goers think Warren is too liberal, up from 23% this spring. (Just 4% say she's too conservative.) And Iowa caucusgoers are a pretty darn liberal bunch! https://t.co/pDI44clAPA pic.twitter.com/KVYY1WCiC1

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) November 17, 2019

- Here’s the rundown of this week’s impeachment testimony lineup.

- A bill to decriminalize prostitution in D.C. (which elicited more than 14 hours of public testimony back in October) will not even get a committee vote.

- Seattle Police Captain Randal Woolery was arrested in an undercover prostitution sting conducted by his own colleagues

- Three Indiana judges are being disciplined after getting into a drunken brawl with strangers in a White Castle parking lot.

- Amazon is funding housing and other services for homeless families in Seattle.

- “I got my rights to do anything I want to do, I’m a police officer.“

- Hong Kong protests and police responses intensified over the weekend.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2QF5FxF

via IFTTT

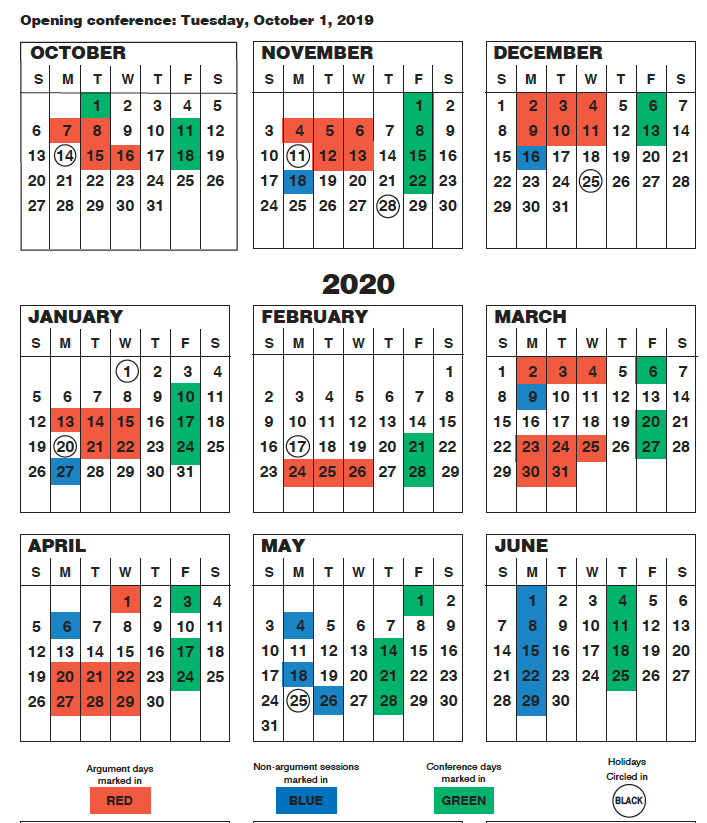

The Supreme Court’s term begins on the first Monday in October. Every year, the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in approximately 80 cases. During the October 2019 term, for example, the Court scheduled 38 argument days between October and April. On most argument days, the Court hears two, one-hour argument sessions, starting at 10:00 a.m. Occasionally, the Court will hear a third case in the afternoon. The argument days are shaded in red on the

The Supreme Court’s term begins on the first Monday in October. Every year, the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in approximately 80 cases. During the October 2019 term, for example, the Court scheduled 38 argument days between October and April. On most argument days, the Court hears two, one-hour argument sessions, starting at 10:00 a.m. Occasionally, the Court will hear a third case in the afternoon. The argument days are shaded in red on the

The Supreme Court does not sell tickets. Generally, the Court reserves at least 50 seats for each argument day for the general public. (The total number of general admission tickets will depend on how many other seats are reserved.) People who want to attend oral arguments form a line along First Street that snakes around East Capitol Street NE. For high-profile cases, the line can form several days in advance. These brave souls have to endure the elements. Before the DACA case, people huddled under tarps to stay dry during the rain. Around 7:00 a.m., the Supreme Court will issue golden tickets, numbered 1 through 50, to the first 50 people on line. Those tickets will generally guarantee admission to the argument. Those who are beyond #50 may be able to attend argument if any seats remain vacant. They may also be able to cycle through, and watch three minutes of oral arguments.

The Supreme Court does not sell tickets. Generally, the Court reserves at least 50 seats for each argument day for the general public. (The total number of general admission tickets will depend on how many other seats are reserved.) People who want to attend oral arguments form a line along First Street that snakes around East Capitol Street NE. For high-profile cases, the line can form several days in advance. These brave souls have to endure the elements. Before the DACA case, people huddled under tarps to stay dry during the rain. Around 7:00 a.m., the Supreme Court will issue golden tickets, numbered 1 through 50, to the first 50 people on line. Those tickets will generally guarantee admission to the argument. Those who are beyond #50 may be able to attend argument if any seats remain vacant. They may also be able to cycle through, and watch three minutes of oral arguments.