When President Donald Trump endorsed “red flag laws” on Monday, he described them as providing “rapid due process” to people accused of posing a threat to themselves or others before suspending their Second Amendment rights. Sen. Lindsey Graham (R–S.C.), who plans to introduce a bill aimed at encouraging more states to enact such laws, says they should provide “robust due process.” But as I note in my column today, due process is neither rapid nor robust under most existing red flag laws, which 17 states and the District of Columbia have enacted. There is little reason to think the situation will improve as more states rush to do something about mass shootings.

Testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee last March, David Kopel, a gun policy expert at the Independence Institute in Denver, emphasized the importance of procedural safeguards aimed at protecting the constitutional rights of respondents in gun confiscation cases. Kopel’s recommendations include requiring that petitions be submitted only by law enforcement agencies after an independent investigation, allowing ex parte orders (which are issued without an adversarial process) only for good cause, limiting them to one week, limiting subsequent orders to six months, requiring clear and convincing evidence, providing counsel to respondents, giving them a right to cross-examine witnesses, letting them sue people who file false and malicious petitions, and giving them advance notice of confiscation orders. Here are some of the ways existing laws fall short of those criteria.

Who can file a petition?

According to a handy summary prepared by the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, just five states (Connecticut, Florida, Indiana, Rhode Island, and Vermont) require that petitions come from police officers or prosecutors. In the other 12 states and D.C., lots of other potentially aggrieved (or well-meaning but mistaken) people, such as blood relatives, in-laws, current and former cohabitants, current and former intimates, physicians, and mental health specialists can also file petitions. A pending California bill would add employers, co-workers, and school personnel to that state’s already lengthy list of potential petitioners.

When are ex parte orders allowed?

Every state and D.C. allow judges to issue gun confiscation orders without giving the respondent a chance to rebut the claims against him. In some states, the standard for such ex parte orders is minimal. New York requires “probable cause” to believe the respondent is “likely to cause serious harm” to himself or others. Other states are stricter. Vermont requires showing by “a preponderance of the evidence” that the respondent poses “an immediate and extreme risk.”

How long do ex parte orders last?

The maximum length ranges from a week in Nevada to six months (for “good cause”) in Maryland. Fourteen days—twice as long as Kopel’s recommendation—is the most common limit.

What is the standard of proof for final orders?

Most states require clear and convincing evidence. But a preponderance of the evidence (any probability greater than 50 percent) is enough in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Washington state, and Washington, D.C.

How long do final orders last?

Orders issued after an adversarial hearing typically last up to a year (twice as long as Kopel thinks appropriate), and they can be renewed. Illinois and Vermont have six-month limits, while Indiana and New Jersey impose no time limit. Instead the respondent has to win back his Second Amendment rights by proving he is not dangerous.

Do respondents have a right to legal representation?

Colorado is the only state that provides counsel to respondents who cannot afford a lawyer or choose not to hire one.

Do respondents get a chance to cross-examine their accusers?

Not necessarily. In some states, Kopel says, “The accuser and witnesses supporting the accuser never need to testify in court, where they would be subject to cross-examination. Instead, persons can simply submit an affidavit.”

Do respondents have a civil cause of action against petitioners who lie?

No state lets petitioners sue their accusers for knowingly misrepresenting facts in their petitions. While dishonest petitioners could theoretically face criminal charges, Kopel says, such cases are hard to prove and are almost never brought. He argues that the threat of litigation is necessary as a deterrent to people who would otherwise abuse the system to hurt people they have a grudge against.

Do respondents have advance notice before gun confiscation orders are executed?

In some states, Kopel says, “a respondent never receives notice of anything until

the police show up to confiscate his or her firearms,” which “creates an inherently volatile and dangerous situation for law enforcement and the public.” He argues that “the safer approach is to authorize no-notice confiscation only when a court has made specific factual findings about why such an approach is needed.”

How do red flag laws work in practice?

The actual performance of red flag laws tends to be worse than the promises on paper. While Indiana notionally requires that a hearing be held within 14 days of a gun seizure, for instance, a 2015 study found that gun owners waited an average of more than nine months before a court decided whether police could keep their firearms. Although Maryland officially requires evidence of an “immediate and

present danger” for ex parte orders, judges issue them in virtually every case.

Even when clear and convincing evidence is required for a final order, the thing to be proven—usually a “significant” risk but in some states a mere “risk,” “danger,” or “risk of danger”—is vague and undefined. When standards are amorphous, judges are especially likely to err on the side of issuing orders, because they imagine that failing to do so could lead to terrible consequences. The possibility that a respondent will unfairly lose his Second Amendment rights is bound to pale in comparison to the possibility that he will use a gun to commit suicide or murder. That psychological dynamic helps explain why judges in Florida issue final orders 95 percent of the time.

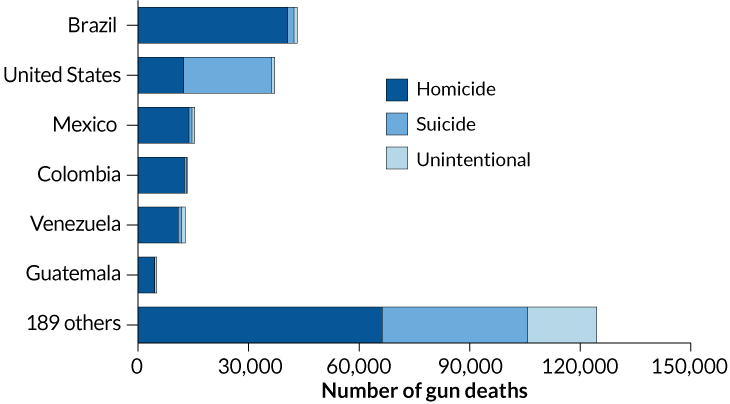

Donald Trump can talk about due process. Lindsey Graham can talk about due process. David French can talk about due process. But when push comes to shove, state legislators will give it short shrift, and so will judges, because they both have strong incentives to cast the net as widely as possible, to better catch potential mass shooters. Never mind that red flag laws are mainly used to protect people against their own suicidal impulses, or that so far there is no real evidence that they prevent homicides. The point is to do something about mass shootings, whether or not that thing works or produces benefits that outweigh its costs, which in this case consist mainly of constitutional rights unjustly lost.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2YXGk6F

via IFTTT