International Man: Economically, politically, and socially, the United States seems to be headed down a path that’s not only inconsistent with the founding principles of the country but accelerating quickly toward boundless decay.

The word “decadence” is often associated with the fall of the Roman Empire, which became morally corrupt—its people lazy, wasteful, and lacking discipline. Many observers have pointed out the US is similarly becoming decedent. How do you see it?

Doug Casey: There’s no question about it; the culture in the US is changing. Where to start? It’s a book-length subject. One thing that absolutely amazes me is that the term “cultural appropriation” has become a buzzword for a lot of people today. The concept is actually completely insane.

It’s bizarre—perverse, really—that the people doing the most whining about cultural appropriation by Americans don’t actually have worthwhile cultures themselves. The fact of the matter is that the only culture in the history of the world that amounts to anything is that of Western civilization. The West has given all of humanity concepts like freedom of speech, freedom of thought, freedom of the press, free markets, individualism, science, and rationality. In addition, the West has created almost all of the world’s great music, literature, architecture, and philosophy

People trying to make cultural appropriation on the part of Americans into a scandal are basically scam artists and race hustlers. I’m talking about blacks who are outraged about white women wearing African earrings. Or Hispanics picketing a couple of white girls who set up a taco stand after visiting Mexico.

I’ve spent a lot of time in the Spanish-speaking world south of the US border. Other than quaint sombreros, some local food, and some basically primitive handicrafts, they don’t have a culture that’s worth anything.

That’s absolutely true of Africa. Africans should be eternally grateful to the West if, when da Gama was rounding the Cape in the 15th century, he’d just thrown out a wheel. But he would have also had to throw out an instruction book. But nobody could read it, because the entire continent south of the Sahara was illiterate.

This is true of most of the primitive world. I hesitate to say “developing world” because development is solely due to imported capital and expertise. If that inflow stops, Africa could go back to the bush, with mass starvation.

The only cultures in the world that can compete with Western civilization are those in the Orient. But what do they have? Frankly, not much, apart from Taoism, Zen, yoga, martial arts, and some great cuisines. Some things of value but not much by comparison to the West.

The fact that Westerners are ashamed of their culture is a sign of the collapse of the West. Most Europeans and Americans are so intimidated by these people squalling about ridiculous things that they don’t even try to defend themselves.

Instead, they agree with their attackers, stick their tails between their legs, and wander off. I don’t doubt Americans will agree to pay “reparations” to blacks for slavery. It’s an absurd concept, about as ridiculous as the English paying me reparations because of what they did to my ancestors in Ireland 200 years ago.

In fact, the Africans exported to the New World were the lucky ones. Their descendants have a standard of living and opportunities 10 or 20 times greater than those still on the continent.

But the fact these things are even discussed is a definite sign of the collapse of the West. It’s very much like what happened in the late Roman Empire.

When Rome was in its ascendancy and at its height, the leaders of Rome were all native Romans or at least native Italians. If they were born in other parts of the Empire, they were of Roman culture and had Roman names and Roman values. They had a stake in their civilization.

But as time went on, all of this started changing.

By the time the barbarians invaded the Empire wholesale—starting with the battle of Adrianople in 378 AD—the handwriting was already on the wall. Within 30 years, the barbarians controlled the entire Empire.

The old political structure had completely collapsed. Native Romans were leaving the Empire, going to barbarian lands, to avoid onerous taxation. The currency was worthless. The economy was in a shambles. The military structure had completely collapsed. None of the soldiers were Italians; they were all barbarians hired as mercenaries. Likewise, here in the US, few Americans in the diminishing middle class want to join the military. The city of Rome itself was sacked in 410 AD and it never really recovered.

International Man: Economically, the US government continues to spend ever-increasing amounts of money. In 2018 alone, the federal deficit was $779 billion—a $113 billion increase from the year before. Politicians on both sides of the aisle are falling over themselves to offer new government freebies that could pay for college, medical care, and the list goes on.

How does this play into the theme of US decadence?

Doug Casey: Well, whether you’re an individual or a family or a country, when you live above your means, you’re almost by that very fact decadent. You’re not planning for the future.

But the US government’s debt and reported deficits represent only current cash outlays, not obligations in the form of future spending. If the deficits were represented with accrual accounting—which is what businesses have to do—the annual deficits would probably be more like $3 trillion.

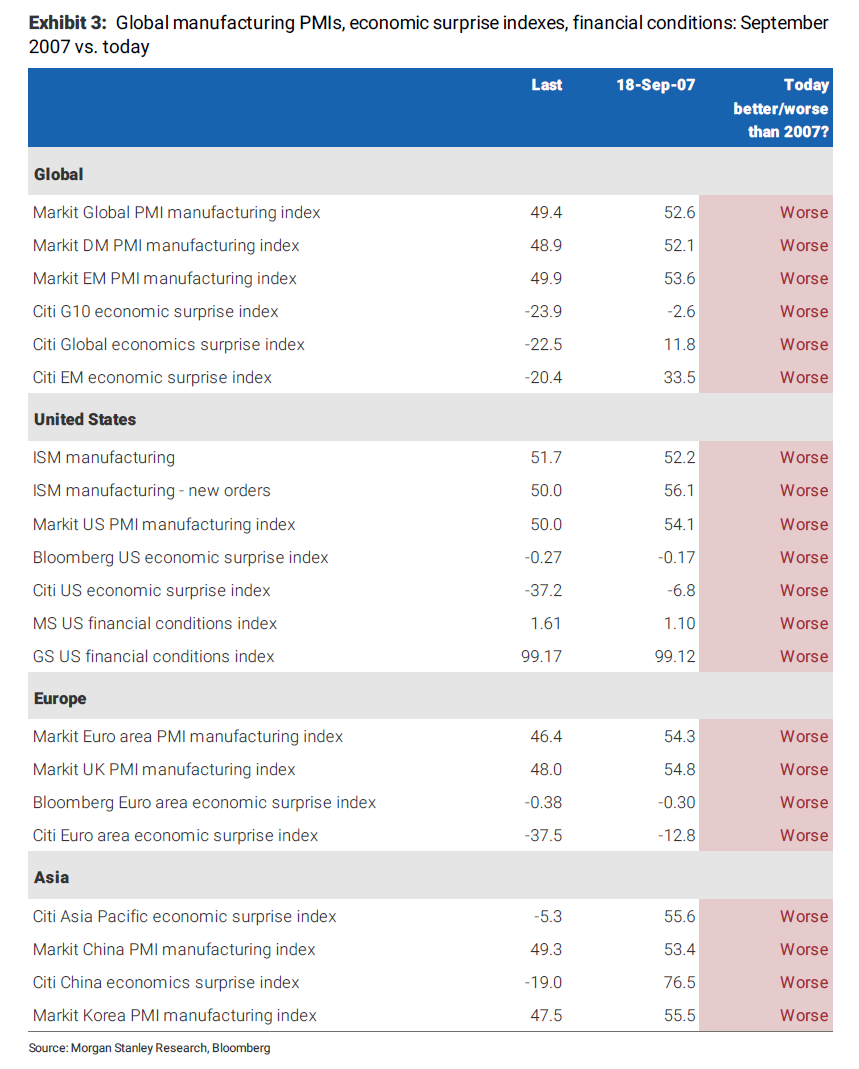

Not to mention that interest rates are artificially suppressed to about 2% in the US. At more normal levels of, say, 6%, the annual deficit would be about $800 billion higher. So the financial situation is actually much, much worse than it seems.

On top of all this is the fact that these deficits come during a time of supposed recovery. But the “recovery” has been ramped up by creating trillions of new dollars and allowing people to borrow at effectively negative interest rates, certainly after inflation. This is all very decadent.

Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die. That’s not the attitude of a rising civilization.

The opposite of “decadent” is to be constructive, disciplined, forward-thinking, and self-respecting. You produce more than you consume and save the difference.

That’s exactly the opposite of what Americans are doing today.

We’re completely decadent.

Small comfort that the Europeans are even worse off than we are.

International Man: On an individual level, Americans are living beyond their means. Many Americans have less than $1,000 in savings.

What does this say about a society?

Doug Casey: It augurs very poorly.

The average American is one paycheck from not being able to pay his rent. When the distortions that have been cranked into the economy over just the last 10 years unwind and the economy as a whole goes downhill again, there are going to be millions of people who can’t pay their rent. Many millions more are going join the 42 million Americans now living on food stamps.

The social repercussions of this are predictable.

The population will get angry; many will go into the streets and riot. They’re going to vote overwhelmingly for some politician who says that he—or quite possibly she—can cure all their problems by giving them free stuff stolen from rich people.

In a way it’s understandable, because the fact of the matter is the rich have indeed been getting richer at an accelerating rate.

Why?

Because they’re the ones that get to stand next to the firehose of money that’s coming out of Washington. They get it first; they get most of it. It’s another sign of a society in decline: the dominance of cronies. That creates a lot of class antagonism.

It’s going to explode and be really ugly. Perhaps one thing keeping a lid on the situation is the huge number of Americans on psychiatric drugs: Zoloft, Prozac, and a hundred others. Perhaps millions of others don’t care as long as their internet connection enables them to play video games.

International Man: Aside from the financial aspect of decadence, what is happening culturally and intellectually in the United States? For example, many Americans are rejecting biological facts in favor of the politically correct fad of the day. Is this a sign of decline?

Doug Casey: The PC types say there are supposed to be 30 or 40 or 50 different genders—it’s a fluid number. It shows that wide swathes of the country no longer have a grip on actual physical, scientific reality. That’s more than a sign of decline; it’s a sign of mass psychosis.

There’s no question that some males are wired to act like females and some females are wired to act like males. It’s certainly a psychological aberration but probably has some basis in biology.

The problem is when these people politicize their psychological peculiarities, try to turn it into law, and force the rest of the society to grant them specially protected status.

Thousands of people every year go to doctors to have themselves mutilated so that they can become something else. Today they can often get the government or insurers to pay for it.

If you want to self-mutilate, that’s fine; that’s your business even if it’s insane. To make other people pay for it is criminal. But it’s now accepted as normal by most of society.

The acceptance of politically correct values—“diversity,” “inclusiveness”—trigger warnings, safe spaces, gender fluidity, multiculturalism, and a whole suite of similar things that show how degraded society has become. Adversaries of Western civilization like the Mohammedan world and the Chinese justifiably see it as weak, even contemptible.

As with Rome, collapse really comes from internal rot.

Look at who people are voting for. It’s not that Americans elected Obama once—a mob can be swayed easily enough into making a mistake—but they reelected him. It’s not that New Yorkers elected Bill de Blasio once, but they reelected him by a landslide. All of the Democratic candidates out there are saying things that are actually clinically insane and are being applauded.

International Man: In fact, in the recent Democratic debate, candidate Julián Castro even mentioned giving government-funded abortions to transgender women—biological men. It received one of the loudest bouts of applause from the audience.

That’s not to mention that two other candidates spoke in broken Spanish when responding to the moderator’s questions.

Doug Casey: As you said, it got a lot of applause.

US presidential candidates speaking in Spanish would be very much like an ancient Roman addressing the Forum in Gothic, not Latin. It’s all over for a culture when it starts using the language of its conqueror. In a restaurant here in Aspen, the owners have a sign in Spanish that refers to the progress of the Reconquista—the recapture of the American Southwest from the Anglos. Perhaps someone will speak Arabic in the next debates.

I hate to sound defeatist, but it’s all over for what was once known as American civilization. The celebrity of AOC is indicative. How else could a 29-year-old Puerto Rican waitress, poorly educated and not very bright, set the political tone for the whole country?

International Man: Is America’s late-stage decadence a product of its political and economic decline or vice versa?

Doug Casey: The decadence we see all around us is arising from every source. Cultural, economic, and political. Cultural decline is the most basic area. Massive immigration of people with different cultures, languages, and religions guarantee it. Especially if they’re coming because of free benefits. Many actually despise traditional American culture, as well as holding the current culture in contempt.

Their views are then reflected in a corruption of the politics. We see that with the apparent acceptance of the Squad—although I prefer to call them the “Gang of Four.” Politics engenders economic distortions. Part of the problem is that politics completely dominates the economy today.

For Trumpers to think that building a wall is going to change things is naïve. A wall will be about as effective as a kid’s sandcastle on the beach to hold back the waves.

The barbarians are already within the gates.

* * *

As Doug Casey discussed, the late stage decadence in the US is contributing to a growing wave of misguided socialist ideas and politicians. All signs point to this trend accelerating until it reaches a crisis… one unlike anything we’ve seen before. That’s exactly why Doug and his team just released this urgent video. Click here to watch it now.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2yhHryU Tyler Durden