All elections are about power—and some shifts in political power are felt for years.

Such was the case 10 years ago, when Republicans rode an electoral tsunami that gave the party its largest share of state legislative seats since the 1920s. That election preceded the once-per-decade redrawing of legislative and congressional districts, and Republicans used their time in the catbird seat to carve out favorable political geography for themselves. Although some of those district maps were eventually overturned by courts and redrawn after yearslong legal battles, Republican gains at the state level in the 2010 election undeniably shaped the country’s political landscape for the past decade.

What the next decade looks like will be decided today.

There are 5,876 state legislative races being conducted on Tuesday—nearly 80 percent of all statehouse seats in the country—and 11 states will elect a governor as well. Beyond the redistricting power, there are significant policy stakes: the National Conference for State Legislature (NCSL), a nonpartisan group that tracks state political action, notes that Congress has passed 163 bills since January 2019 while states have enacted 15,000 new laws.

Democrats have clawed back some of what they lost in 2010, but NCSL data show that Republicans still hold 52 percent of America’s legislative seats and control 59 of the 98 partisan chambers in statehouses. (Nebraska has a unicameral legislature that is technically nonpartisan, but Republicans have an unofficial majority there too.)

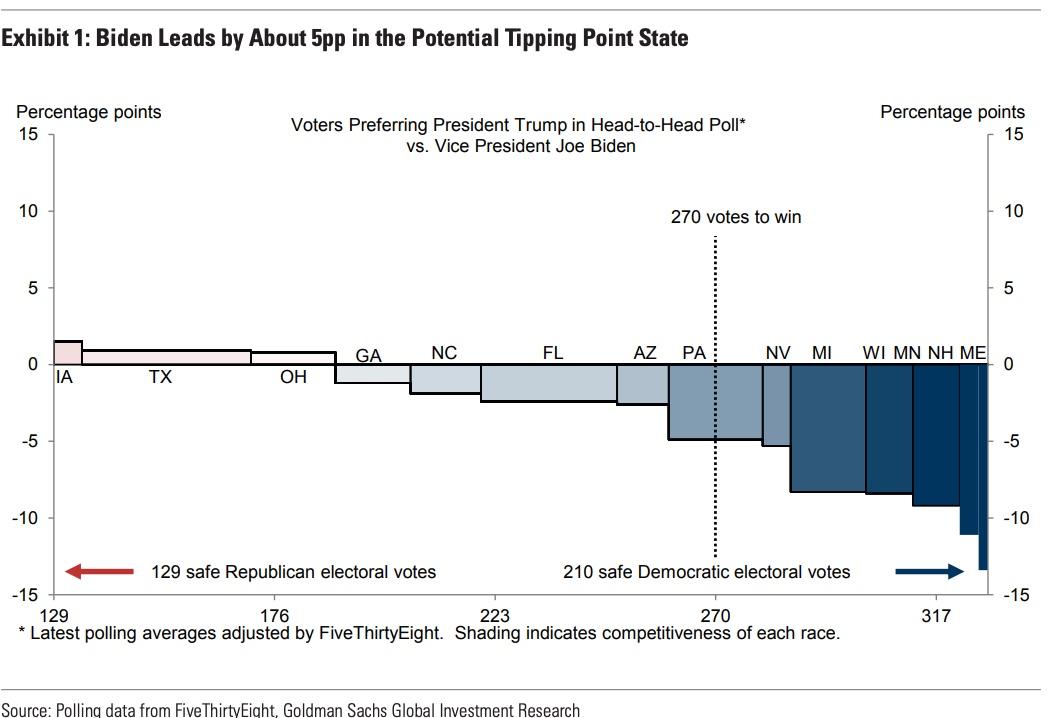

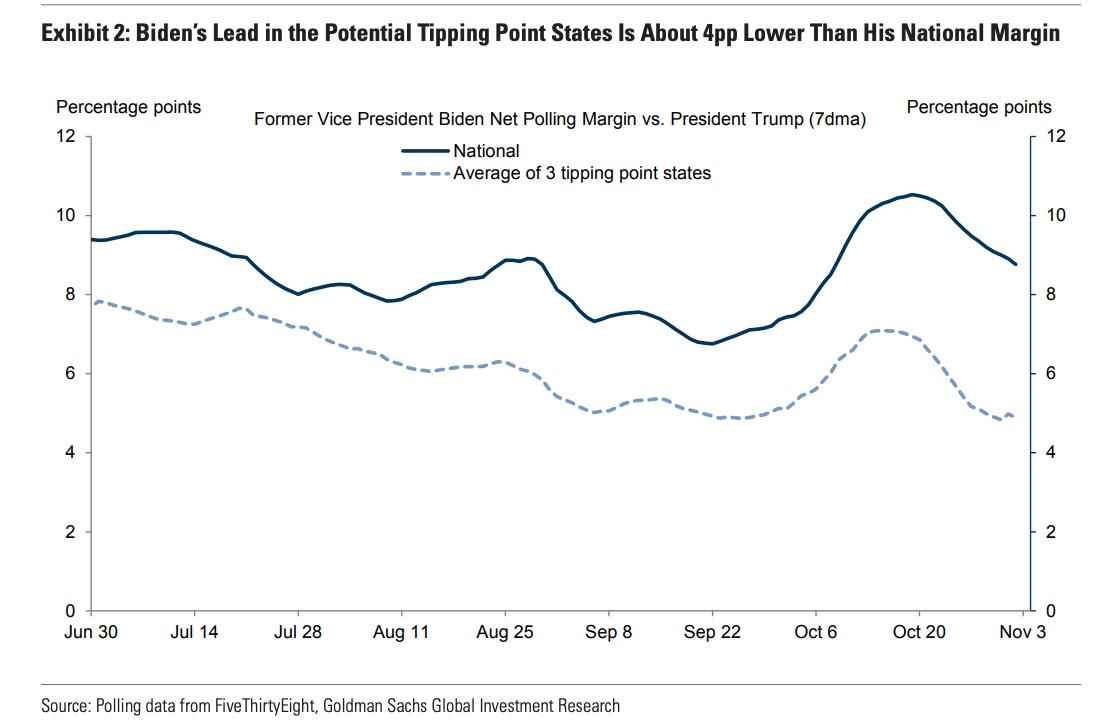

A big night for Democrats could see them vault into power in some places where they haven’t had a majority for a long time. In Pennsylvania, the state that seems to be at the center of so much of this election, Democrats need to flip nine House seats and four Senate seats to take control of the legislature ahead of redistricting. Pennsylvania’s Senate hasn’t had a Democratic majority since 1980, making it a good marker for judging the strength of this year’s possible “blue wave.”

That’s the type of historical result Democrats will have to achieve if they want to match the Republican shellacking of 2010, when the GOP swung control of an incredible 21 legislative chambers.

Democrats are eyeing potential swings of power in both chambers in Arizona, where Republicans enter the election with a two-seat majority in the state House and a three-seat edge in the state Senate. Democrats haven’t held either chamber in Arizona in more than 40 years. Republicans are also playing defense in the Michigan state House, where they have a seven-seat advantage, and in the Minnesota state Senate, where they hold a three-seat majority.

A few gubernatorial contests could see power shift as well, though for the most part these races are less competitive this year. Incumbent Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, is likely to face a close contest in North Carolina, and Missouri Gov. Mike Parson, a Republican, could too. Other than that, the only interesting race is Montana’s incumbent-less gubernatorial contest, which seems wide open.

But even if Democrats can match the Republican wave of 2010, their power to redraw districts will be blunted, in part, by Democratic-led efforts to rein-in partisan redistricting during the past decade.

At least 114 congressional seats will be subject to redistricting commissions in 2021, according to the Cook Political Report. Those commissions operate differently in various states and have a mixed record when it comes to thwarting partisan outcomes, but they certainly remove a degree of power from lawmakers’ hands. The number of congressional districts drawn by a commission could rise to 125 if Virginia voters approve a ballot initiative on Tuesday that would create such a commission.

There are another 58 congressional districts in three key states—Florida, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania—where the next set of congressional maps will be subject to newly created standards set by state courts. And there are seven congressional districts that can’t be gerrymandered because they are at-large districts covering the whole state.

That still leaves 245 seats in Congress—a little more than half—for which state legislators will have outsized control. All eyes are understandably on the top-of-the-ticket race between President Donald Trump and former vice president Joe Biden, but the outcome of statehouse races might have more lasting consequences.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2Jrbwos

via IFTTT