Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

The line of dominoes that is already toppling extends around the entire global economy and financial system. Plan accordingly.

That China faces structural problems is well-recognized. The list of articles in the August issue of Foreign Affairs dedicated to China reflects this:

Xi’s Gamble: the Race to Consolidate Power and Stave Off Disaster

China’s Economic Reckoning: The Price of Failed Reforms

The Robber Barons of Beijing: Can China Survive its Gilded Age?

Life of the Party: How Secure Is the CCP? (Chinese Communist Party)

These are thorny, difficult issues: a demographic cliff resulting from the one-child policy, soaring wealth-income inequality, pervasive corruption, public health issues (diabesity, etc.), environmental damage and a slowing economy.

What the conventional analysts do not fully grasp, in my view, are 1) the existential threat to the CCP and China’s economy posed by its unprecedented, metastasizing credit-asset bubble and 2) its incipient energy crisis.

As I explained in a recent blog post, What’s Really Going On in China?, the CCP and the government informally institutionalized moral hazard (the disconnection of risk and consequence) as a core economic policy.

Every financial loss, no matter how risky or debt-ridden, was covered by the state (via bail-out, refinancing debt, new loans, etc.) as a “cost of rapid development,” a reflection of the view that some inefficiency and waste was inevitable in the rapid development of industry, housing, infrastructure and a consumer economy.

What China’s leaders did not fully understand was this implicit guarantee of bail-outs–the equivalent of “The Fed has our backs”–incentivized debt-funded speculation as the lowest-risk, highest-return “investment,” especially when compared to low-profit, risky investments in low-margin export industries. (Recall the average profit margins of Chinese exporting enterprises is 1% to 3%.)

This is the hidden driver of China’s sagging productivity and economy: debt in all sectors is skyrocketing to fund speculation, not productivity.

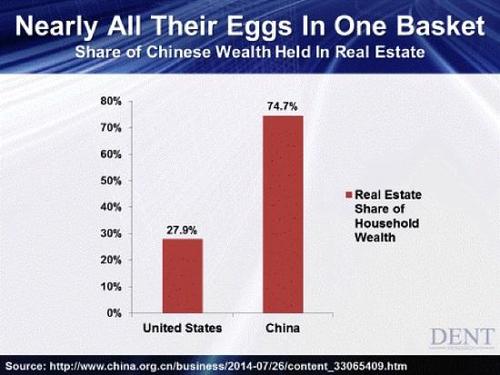

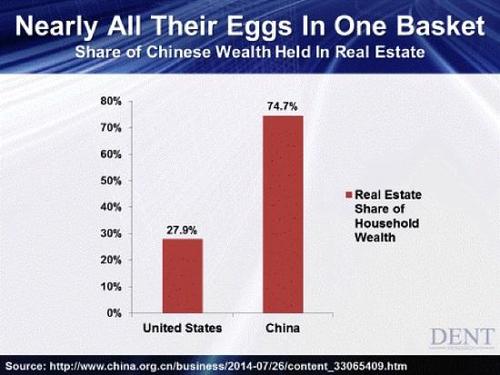

This institutionalization of moral hazard has incentivized the least productive and highest-risk gambles–not just for large conglomerates like EverGrande, but for middle-class households who’ve invested in the shadow-banking system (unregulated private-sector pools of capital lent out to risky borrowers at high rates of interest) and bought second, third and fourth “investment” flats.

The contradictions in this mass investing of savings in empty condos are systemic and dangerous: 1) once a flat is rented, it loses value due to being “used” and 2) the vast majority of the market for “investment” flats is illiquid, as most new buyers want a new flat, not an old one, so the market for old flats is extremely thin outside the most desirable inner rings of Beijing and Shanghai.

This mass investment in illiquid empty flats has generated social and financial perversities: now that flats in desirable areas cost 30-40 times an average white-collar salary, young people must vacuum up the entire extended family’s savings in order to afford a flat. Those young men who are unable to buy a flat find their marriages prospects are dismal.

One result of the marriage of state control and private-sector Wild-West speculation is a truly vast wealth-income divide that is bound up with corruption in a mutually reinforcing feedback: the richer you become, the closer to power you get, and vice versa.

Since China’s informal shadow-banking system is opaque even to state regulators, it’s quite possible that China’s leaders do not have a full grasp of the extent of systemic risk bound up in the excesses of shadow banking. To paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld’s famous dictum, this is an unknown unknown for China’s policy makers.

This truly monumental accumulation of debt and speculation is now an existential threat to the Party on two levels:

1) since all bubbles pop regardless of any other conditions, when this bubble pops, the economic blow will be severe enough to threaten the Party’s control of the economy

2) the crushing of phantom wealth will cause people to seek a scapegoat, and the Party is Target #1 since it coddled the well-connected and wealthy but did not protect the 99% from the dire consequences of the bubble bursting.

Having engineered the bubble’s expansion by creating mountains of debt and implicit promises of bail-outs, the CCP and government have backed themselves into a corner: there is no pain-free way to deflate a speculative bubble of such astounding proportions.

Considering the life history of President Xi (especially his first-hand experience of the Cultural Revolution 1966-1976), his writings and his consolidation of power, it is very clear to me that Xi understands the bubble is close to escaping his control and so time is short and the policy options are limited to triage, that is, saving the healthiest and letting Nature take care of those closest to expiring.

I also see evidence that Xi grasps the absolute need to break the near-universal confidence that the state will bail out everyone who borrows and speculates so wildly that their gambles go bad.

The general assumption is that “China can’t afford to let Evergrande fail” because this enormous conglomerate will obviously topple many dominoes, generating great financial pain.

I think the that President Xi’s view is the opposite: “we can’t afford to bail out Evergrande” because that would open the floodgates of moral hazard that Xi is trying to close.

The state bailing out private-sector gamblers (and state-owned enterprises) is what led to the massive moral hazard-debt bubble that Xi is determined to pop now while he still can control the process.

In other words, President Xi understands this is the do-or-die moment to regain control of an out-of-control moral hazard driven financial bubble, and the only way to do so is to push the losses onto everyone with exposure, the driver being the stark choice to either regain control by popping the bubble now or letting it expand and implode in an uncontrolled (and hence Party-threatening) fashion.

Xi concluded that the first step to being able to push the losses onto everyone with exposure to speculative bets was to consolidate power to such a degree that the usual self-interested factions that would use their power to evade the consequences could be forced to accept their share of the losses.

Given the history and structure of the Party, this required Xi to extend his control to levels not seen since Deng or Mao.

In my view, Xi correctly concluded the hour was getting late and the institutional resistance to the end of the implicit promises of state bailouts and endless debt expansion could only be overcome if his political power was near-absolute.

The popping of moral hazard and the debt-speculation bubble are necessary to preserve CCP and state power; half-measures that protected corrupt cronies would only increase the public’s outrage when the bubble finally burst.

In this light, Xi’s multi-year campaign against the most visible corruption and his recent touting of “common prosperity” have set the stage for his forcing the end of moral hazard and the controlled demolition of the excesses of debt and speculation that have harmed the economy and threatened the control of the CCP.

Now comes the grand ironies. China’s ability to generate stupendous amounts of new debt basically bailed out the global economy in 2008-09, 2015-16 and 2020. Yes, the Federal Reserve bailed out the global banking sector (to the tune of $16 trillion in backstops and credit lines) in 2008-09 and inflated a speculative bubble in the U.S. by creating $3.5 trillion in quantitative easing, but China’s expansion of debt was an equally important source of global demand, which is what stopped global economies from sinking into recession.

The cost of these “saves” were not understood at the time: the elevation of moral hazard to quasi-religious status in the U.S. and China and the expansion of debt-funded speculative bubbles to unprecedented heights.

There are only two policy options:

1) Grasp the nettle and refuse to bail out debt-funded speculative excesses, thereby popping the Everything Bubble, or

2) play the game of keeping the bubble expanding until it implodes on its own, an end-game made inevitable by the systemic instabilities intrinsic to bubbles.

Xi has correctly chosen Policy #1, and to do so has positioned the Party as the defender of the people, i.e. anti-corruption, shackling the Big Tech billionaires like Jack Ma, and announcing that the state will not bail out EverGrande.

The Federal Reserve and the political leadership of the U.S. have foolishly chosen Policy #2, inflating the bubble while letting the consequences of this moral hazard bubble–wealth-income inequality and corruption–explode higher, fatally undermining the credibility of both the Fed and America’s political class.

As the supply chain disruptions have revealed, the global economy and financial system are tightly bound systems, and as such are extraordinarily exposed to the risks of cascading collapses as key nodes become chokepoints or break down.

While the Federal Reserve prints trillions to further inflate the bubble, the global energy shortages are already crippling key sectors in the economies of China and the EU. Reality is about to intrude on the Fed’s fantasy that speculative bubbles can remain disconnected from the real-world economy forever.

In summary: the popping of the global Everything Bubble is not Xi’s goal; it is the inevitable second-order effect (collateral damage) of China’s debt-speculation bubble popping.

Given the tightly-bound financial system, the collapse of EverGrande is far more the story of dominoes toppling rather than direct losses: it’s not the direct losses that will bring down the global financial system, it’s the dominoes toppling as those who take the direct losses implode and become insolvent, missing their loan/bond payments, being unable to meet their counterparty obligations, and so on.

The consensus in the West is that China cannot afford to let its bubble pop because the pain will be so severe. Those who believe this have a poor grasp of Chinese history, especially in the 20th century.

If crashing China’s bubble is the nuclear option, Xi has reason to be confident he can push the pain level to 11 and most will accept it, and those who don’t will join Jack Ma in forced retirement.

I reckon Xi views ending moral hazard and popping the bubble in China as a situation that will only get worse the longer he puts it off.

The grand irony now is that rather than saving the global economy by expanding its own debt bubble, China will pop the global Everything Bubble. To state the obvious, being a linchpin in the global economy makes China a consequential domino. Anyone who thinks the Fed’s speculative bubble in the U.S. can magically become immune to the collapse of tightly-bound dominoes is indulging in magical thinking.

China’s extreme excesses of debt and speculation are already unraveling, and Xi is backed into a corner. There is no cost-free escape, only triage, and Xi has charted a path to preserve the Party’s control by forcing everyone with exposure to absorb the inevitable losses when unprecedented bubbles pop.

The line of toppling dominoes extends around the entire global economy and financial system. Plan accordingly.

* * *

This essay was first published as a weekly Musings Report sent exclusively to subscribers and patrons at the $5/month ($54/year) and higher level. Thank you, patrons and subscribers, for supporting my work and free website.

If you found value in this content, please join me in seeking solutions by becoming a $1/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

My recent books:

A Hacker’s Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World (Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Pathfinding our Destiny: Preventing the Final Fall of Our Democratic Republic ($5 (Kindle), $10 (print), ( audiobook): Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake $1.29 (Kindle), $8.95 (print); read the first chapters for free (PDF).

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 (Kindle), $15 (print) Read the first section for free (PDF).