I hope you squirreled away that cool 16 cents you saved on your Fourth of July barbeque this year. Across the board, prices seem to be going up, up, up.

Gas is more expensive (up 42.7 percent). Cars and trucks, too (up 7.6 percent for new and 31.9 percent (!) for used). Your wallet is surely feeling the burn at the grocery store (up 3 percent). Meat, in particular, is getting really expensive (up 10.5 percent), to the sure delight of the anti-animal food crusaders out there. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ official measure of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), pretty much everything is more expensive across the board: 5.4 percent more expensive when compared to last year, according to government bean counters.

Watch how you talk about this seeming inflation online, though. And watch what you read, too.

We know we need to be on the lookout for wrecking misinformation when it comes to our health, our elections, and our political class’s networking equipment. Now we can add our economy to the mix. According to some experts, talking about rising prices could be extremely dangerous to our democracy.

This problematic price commentary is emanating from some interesting quarters: namely, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, whose platform is among the goodest of boys in sniffing out and slapping warning labels on dangerous content like obituaries and reports on errant laptops.

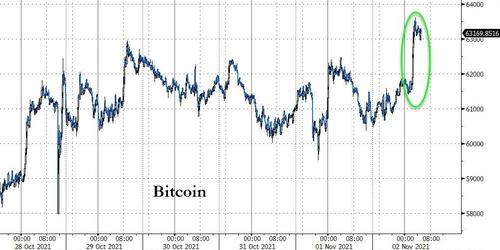

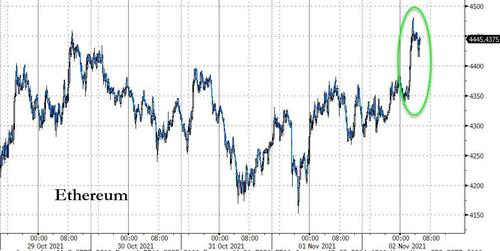

Dorsey recently took to his microblogging platform to offer some thoughts on what the officials have assured us is transitory inflation. The Bitcoin aficionado and also-CEO of payment platform Square tweeted: “Hyperinflation is going to change everything. It’s happening.” He got an assist from fellow very online tech billionaire Elon Musk who agreed that “short-term we are seeing strong inflationary pressure.”

Plenty of experts jumped in to fact check him. Hyperinflation, they say, is a rare and specific event involving periods of 50 percent inflation or higher within one month that has only occurred a few times in history. We all know about the Weimar Republic and Zimbabwe. Actually, the United States had a few brushes with almost or basically hyperinflationary events following the Revolutionary and Civil Wars—remember those continentals from high school history? But we’re far from hyperinflationary, our beloved and trusted experts say. And while we’re on the subject, maybe we need more inflation anyway.

Okay, maybe “hyperinflation” was a little dramatic. Let he who has never exaggerated on social media for effect cast the first stone. But most people got the picture: young Americans on Twitter are about to experience an inflationary episode unlike anything they’ve seen.

The criticism went beyond merely correcting someone’s usage of a technical economic concept. For some, this should be a bannable offense.

Notably, a writer for WIRED clucked that “like ‘divorce’ in a marriage”—or, for the season, like “Beetlejuice” in a haunted Connecticut country home—”this word @jack” should not be uttered unless you’re trying to bring it into being.” Shame on him. “How insanely reckless to tweet this. Immoral. Jack, ban thyself.”

Immoral! Are inflation hawks the new hate speakers now?

It is true that expectations do affect behavior and therefore prices. But any brouhaha Dorsey could stir up with his monetary shitpost obviously pales in comparison to the potent macroeconomics factors—spending and printing bonanzas, high debt overhangs, lockdown policies, and the current situation with the supply chain, to name a few—that are truly driving the “transitory” inflation that our widely respected experts do admit.

What is truly reckless is the suggestion that people should be scared to talk about their experience with everyday prices or risk reprisals. Ironically, censoring talk about rising prices is exactly what you’d expect to see in a high inflationary or hyperinflationary scenario.

Argentina, which has struggled with persistently high levels of inflation, reported official price numbers that were so unbelievable that independent economists started publishing their own. The government moved to punish anyone who deviated from the official narrative on inflation with fines of $120,000.

When things get really bad, the government simply stops publishing price data at all. This is what happened in Venezuela, whose central bank merely stayed mum when monthly inflation started to shoot up into the double-digit zone. Zimbabwe, a country almost synonymous with hyperinflation, again recently stopped reporting inflation data.

Thankfully, we’re not quite at the point where the government is pulling down price data and rounding up dissidents. We’re just hounding rich guys with FU money and the powers of platform censorship to STFU about inflation and stop other people from talking about it too. At least he didn’t pull the tweet down or apologize. But if Jack Dorsey can’t talk about rising prices on Twitter without major controversy, what hope do plebs like us have?

Hopefully Dorsey’s convictions will be strong enough to head off his Trust and Safety Team’s polite suggestions to start fact-checking and labeling inflation claims like his. He feels strongly about monetary sovereignty; it’s like his one thing. But he’s clashed with them publicly before and got overruled. Maybe Twitter gets a phone call strongly encouraging them to start countering economic misinformation. And Twitter is just one platform. Others could very well start massaging opinions on rising prices with their own bags of tricks. We can’t count on centralized platforms to protect our abilities to speak freely about inflation.

It’s good to start planning ahead. The technologist Balaji Srinivasan has started a $100k bounty for a censorship-resistant inflation dashboard that could accurately report prices through future monetary headwinds. It would be decentralized, which means that anyone could contribute price data and no one could shut it down or remove information that certain people don’t like. If built, we won’t have to fear that the government can easily snuff out independent economic data. Government economists could pull down whatever datasets they usually maintain, as states often do in inflationary events. This kind of system would provide a much-needed private backup.

The massaging of public opinion in response to perceived government failures has by now become something of a meme. First, it’s not happening. Then, it’s happening, but only temporarily. Then it’s happening because of Bad People and you’d better not contribute. Finally, it’s happening to you, and that’s A Good Thing. Depending on where you look, you can find some version of all of these narratives.

But rising prices affects everyone in a very immediate and material way, unlike some other political footballs. And it’s often a key procyclical indicator of establishment collapse. The stakes here are high, so the attempted controls on discourse may be more desperate. Keep an eye out.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3ECFcpX

via IFTTT