Authored by Aladair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

Gold has never been more attractive…

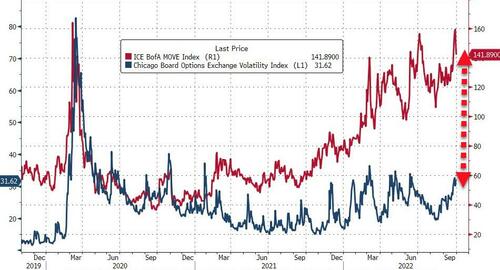

In our lifetimes, we have not seen anything like the developing economic and financial crisis. Rising interest rates are way, way behind reflecting where they should be.

Interest rates have yet to discount the continuing loss of purchasing power in all major currencies. The theory of time preference suggests that central bank interest rates should be multiples higher, to compensate for the current loss of currency purchasing power, enhanced counterparty risk, and a rapidly deteriorating economic and monetary outlook.

There is no doubt that the majority of investors are not even aware of the true scale of danger that interest rates pose to their financial assets. Some wealthier, more prescient investors are only in the early stages of beginning to worry. But if you liquidate your portfolio, you end up with depreciating cash paying insufficient interest. What can you do to escape the fiat currency trap?

This article argues that having everything in fiat currencies is the problem. The solution is a flight into real money, that is only physical gold — the rest is rapidly depreciating fiat credit. Owning real money is the only way to escape the calamity that is engulfing our current economic, financial, and fiat currency world.

Avoiding risk to one’s capital

From conversations with family and friends, one detects an uneasy awareness of increasing risk to investments. There are two broad camps. The first and the majority are only aware that interest rates are rising, and their stocks and shares are falling in value but fail to make the connection fully. The second camp is beginning to worry that there’s something very seriously wrong.

Investors in the first camp have usually delegated investment decisions to financial advisers, and through them to portfolio managers of mutual funds. They have taken comfort in leaving investment decisions to the experts, and besides the odd hiccup, have been rewarded with reasonably consistent gains, certainly since the early noughties, and in many cases before. They trust their advisers. Meanwhile, their advisers are rewarded by the volume of assets under their management or by fees.

Both methods of reward ensure that the vast majority of professional managers and advisers are perennially bullish, further justified by that long-term bullish trend.

This leaves the majority of investors being led into believing that falling financial asset values represent a buying opportunity. After all, their experience for some time has been that it is wrong to sell when markets fall, because they have always recovered and gone higher. And this is the approach promoted by the majority of professional financial service providers because they are always bullish.

The other far smaller camp is comprised of those who think more for themselves. They are beginning to make a connection between rising interest rates and falling markets but are badly underestimating the extent to which interest rates should rise.

This camp knows that the sensible thing to do when interest rates rise materially is to sell financial assets. They know that investing in physical property, tangible assets, is equally dangerous because at the margin prices are set by mortgage interest rates which are now rising. But they equally find that just sitting on cash is an unattractive proposition, with consumer prices rising and chipping away at its purchasing power. So, what is to be done?

Just leaving it in the bank pays derisory interest. And besides, the proceeds of liquidated portfolios usually exceed government deposit guarantees, which means taking onboard the risk that banks might fail. There are things that can be done, such as investing in short term government bonds as a temporary solution, and perhaps buying some inflation-linked government bonds (TIPS). Other than investing in TIPS, the loss of purchasing power problem remains unresolved. And increasingly, these savvy investors are now waking up to currency risk, particularly if they are British, European, or Japanese. The cost of investment safety in nearly all currencies is rising relative to the dollar.

I tell these people that the problem is simple: they have all their eggs in a fiat currency basket. The black and white solution is to get out of fiat by selling financial assets and the fiat cash raised by hoarding real money, that is physical gold in bar and coin form. The argument usually falls on deaf ears, because people only understood the monetary role of gold before the Second World War. That generation has mainly passed away. Why gold is so important has to be explained all over again to a sceptical audience.

We then meet two further barriers raised by the sceptics: gold yields nothing, when investors have been used to receiving dividends and interest. And if gold is the answer, why is it performing so badly? These questions will be addressed.

But all is at stake. Driven by interest rates rising even more and as the bear market continues, investors relying on investment managers and financial advisers will lose nearly everything.

A seventies redux

Global economic conditions today are strikingly similar to UK financial markets in late-1972 and early 1973. Previously, in the autumn of 1970 the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Tony Barber, had come under pressure from Prime Minister Edward Heath to stimulate Britain’s economy by running an inflationary budget deficit, combined with a deliberate suppression of interest rates from 7% to 5%. Heath was a Keynesian disciple. And in those days, the Bank of England was under the direct command of Heath’s government, its so-called independence only arriving far later.

The rate of price inflation rose slightly from 6.4% in 1970 to 7.1% in 1972. The inflationary consequences of the Barber boom and the reduction of interest rates to negative real values were beginning to bite. Meanwhile, investors had enjoyed an equity bull market. Consumer price inflation then began to rise in earnest. In 1973 it was 9.1%, in 1974 16%, and in 1975 a staggering 24.2%. All this is being replicated today — we are probably where Britain was in late-1972.

While the dramatic increases in the rate of price inflation were unforeseen in 1972, being far greater today the stimulus of budget deficits and suppressed interest rates is having a more rapid effect. The gap between official interest rates and the rate of price inflation is magnitudes greater, with the Bank of England’s base rate at 1.75% and consumer prices rising at 8.6%. Even the Bank expects significantly higher CPI rates, with independent estimates forecasting yet higher CPI rates in the new year. Similar stories are to be found worldwide. The comparison with the UK in the early 1970s suggests the inflationary and interest rate consequences today are likely to be even more dramatic for financial assets and for the currencies themselves.

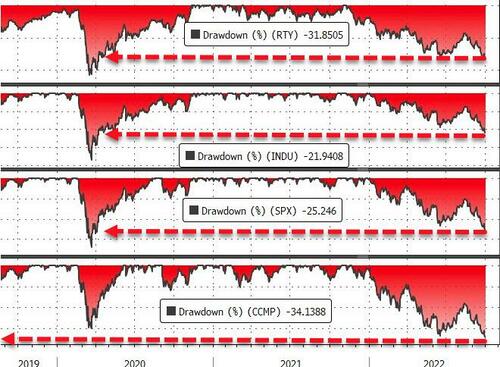

In May 1972, the FT30 Index (the headline measure of share prices at that time) peaked at 534, and a year later had already declined significantly, as interest rates began to rise. In late-October 1973 the bubble in commercial office property began to implode. The proximate cause was the rise in short-term interest rates from 7.5% in June 1973 to 11.5% in July, and 13% in November. Consequently, banks which were lending to commercial property speculators collapsed in the notorious secondary banking crisis. And the FT30 Index continued to decline until early-January 1975, losing 74% from the May-1972 peak. Similarly, this is beginning to play out today.

What’s happening now differs in some key respects from the UK in the early seventies. From negative and zero starting points, interest rates have much more substantial increases in prospect. The gap between bond yields and consumer price inflation is now far larger in the US, EU, and UK than anything seen in the early seventies. It suggests the consequences of rising interest rates today are likely to be far more financially violent than that experienced in the UK between May 1972 and January 1975. We will be lucky if equity markets lose only 74% this time.

But overall, the lesson is clear: sharply rising interest rates are lethal for investors.

We now turn to gold. Bretton Woods having been suspended in August 1971, the price of gold in sterling rose from £17.885 per ounce at that time when sterling interest rates were 6%, to over £40 when interest rates were raised to 13% in November 1974. The lesson learned is that the best hedge out of an inflation-driven collapse of conventional investments is gold. The common belief that rising interest rates are bad for gold because it has no yield is disproved.

Furthermore, the evolution of investment services since the 1970s is worth noting. In those days, a good stockbroker was skilled at steering his clients through the dangers to their wealth from market uncertainties. Admittedly, his clients were never the pre-packaged masses, but were typically individuals with personal wealth whom he personally knew.

Today, passive investors are little more than cannon fodder for a system that absolves itself of any responsibility for outcomes. They are a majority that always get wiped out by delegating all decision making to the so-called experts.

Only those who think for themselves have come to understand that there is something seriously wrong. Investment risks are escalating, and investors must take proactive steps to protect their capital. Unlike their contemporaries in the 1970s who were not so intellectually corrupted by Keynesianism, they have less knowledge of gold, and why it performed so well as an asset in that decade. They need to have a crash course in understanding money and credit, and the distinction between the two.

Gold is money — everything else is credit

So said John Pierpont Morgan in his testimony before Congress in 1912. He was not expressing an opinion, but stating a legal fact, a legal fact which is still true to this day. Despite all attempts by the authorities to persuade us otherwise, despite periods of bans on ownership and Roosevelt’s outrageous confiscations of gold bullion and coin from the people he was elected to represent, the legal position of gold being money and the rest only credit remains the case. It is why central banks accumulate and retain large reserve balances in gold, and why they refuse to part with them. It is why in official circles the topic is taboo.

Ever since the end of barter many millennia ago, transacting people have used media whose primary function was to allow an exchange of goods. Over time, many forms of money were tried and discarded, leaving metals, particularly copper, silver, and gold universally regarded as most durable and capable of being rendered into recognisable coins of a standard weight. Our coins today reflect this heritage. While not containing the original metals, they often reflect the metals’ colours: the highest value looking like gold, intermediate silver, and the lowest copper.

A few thousand years passed before the Roman jurors ruled on monetary matters. Roman jurists were independent from the state. And despite many attempts by emperors and their henchmen to overturn their rulings, their rulings were robust and survived.

Jurisprudence, or the science of law, became an independent profession in the third century B.C. Five centuries later, in the second century A.D., the classical era began. From then onward, the legal solutions offered by independent jurors received such great prestige that the force of law was attached to them.

Of particular interest to our subject were the rulings of Ulpian, who defined the status of moneyin the context of banking. On “depositing and withdrawing”, Ulpian starts with a definition:

A deposit is something given another for safekeeping. It is so called because a good is posited [or placed]. The preposition de intensifies the meaning, which reflects that all obligations corresponding to the custody of the good belong to that person.[i]

He then makes a distinction between a regular deposit; that is a specific item to be retained in custody, and an irregular deposit of a fungible good, stating that:

…if a person deposits a certain amount of loose money, which he counts and does not hand over sealed or enclosed in something, then the only duty of the person receiving it is to return the same amount.[ii]

Ulpian’s rulings in the early third century still define money and banking today. They were consolidated in The Digest, one of four books in the Corpus Codex Civilis established by order of the Emperor Justinian in about 530AD. Roman law became the basis of all significant European legal systems, and through Justinian, Ulpian’s rulings continue to apply.

In Britain’s case, Rome had left long before Justinian’s emperorship, so Roman rulings were not an explicit part of common law. However, when common law and the Court of Chancery merged in 1873 the distinction between custody deposits and mutuum contracts (when fungible goods such as money coins are transferred to another’s possession under a commitment to return a similar quantity) became unquestionably recognised, fully validating what had been common banking practice since the seventeenth century.

Of the three forms of metallic money, gold became the standard in Britain in 1817, and all significant currencies which had not done so before became exchangeable for gold in preference to silver in the 1870s. It is therefore correct to say that today, gold is the only form of true money in our monetary system, while silver’s monetary role is merely dormant.

The rest is credit. Bank notes issued by central banks, are the primary form of credit. No longer exchangeable for gold coin, they are simply issued out of thin air. In addition to the government’s general account with its central bank, in modern times they have started issuing other forms of credit, all of which are provided through commercial banks and reflected in commercial bank credit, such as payment for securities bought from investing institutions which do not have accounts at the central banks. This is the payment mechanism for quantitative easing.

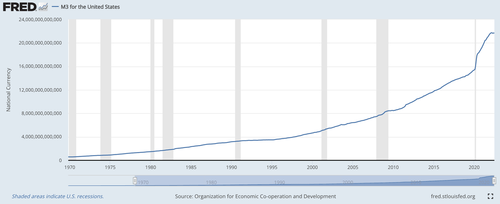

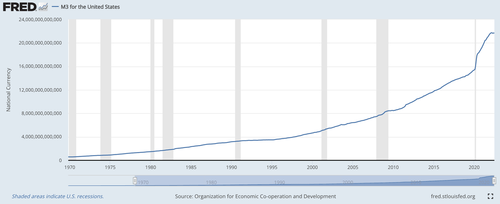

Commercial bank credit makes up all the circulating media which are not banknotes, typically representing over 95% of commercial transaction settlements. Bank credit can be expanded at will. The chart below shows how the sum of bank notes and commercial bank credit in US dollars measured by M3 has increased since 1970.

Colloquially, this is monetary inflation. More correctly, it is credit inflation because true money, that is gold, is almost never used in transactions. Since the suspension of Bretton Woods in 1971, the amount of M3 credit has increased by 33 times. At the same time, the price of gold has increased by 38 times from $42.22 per ounce, the rate at which it was fixed to the dollar before Bretton Woods was suspended. In other words, real money, which is gold in metal form, has fully compensated for the devaluation of the dollar due to the increase in dollar credit since 1971, though the credit expansion since Roosevelt devalued the dollar against gold is supplemental to these figures. There is more on this later in this article.

If you bought gold when Nixon suspended the Bretton Woods agreement, you would have preserved the purchasing power of your money compared with owning bank notes or possessing instant withdrawal bank deposits. There were ups and downs in the relationship between gold and paper currency, but to make it clear, gold coin or bullion can only be compared with cash and non-yielding bank deposits. It cannot be compared with a yielding asset. Gold is not an investment. But owning bonds, equities, or residential property is most definitely investing for a return.

Normally, it makes sense to spend and invest instead of holding onto cash, whether that cash be true money or bank credit. After all, the reason to maintain money and paper credit balances is to enable the buying and selling of goods and services, with any surplus being put to use by investing it. But it must be understood that in these times of rapidly depreciating currency, an investment must also overcome the hurdle of currency depreciation.

When stocks are soaring and they pay dividends, the hurdle can be overcome. However, we must introduce a note of caution: when stocks are soaring, it is generally on the back of bank credit expansion which leads to a temporary fall in interest rates, a situation which is reversed in time.

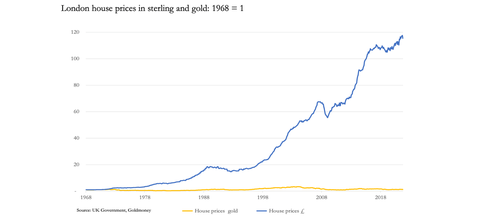

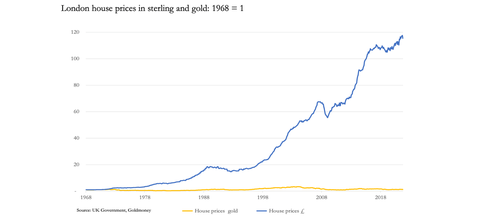

The next chart puts residential property prices in context. Priced in sterling, London property prices have soared 114 times since 1968. In true money, which is gold, they have only risen 29%. But the average property buyer buys a house with a mortgage, putting down a partial payment, while paying off the mortgage over time, typically twenty or thirty years. His capital value will have multiplied considerably more than the 114 times reflected in the index, against which mortgage payments including interest will have to be offset to properly evaluate the investment. Furthermore, the utility of the accommodation afforded is not allowed for but is an additional benefit of property ownership.

Taking currency prices, mortgage finance, and yield benefits into account, investment in a home in London has proved to be a better use of capital than hoarding gold, but not by as much as you would think. As remarked earlier in this article, at the margin property values depend on the cost of mortgage finance, which is tied to interest rates. So, what is the outlook for interest rates?

Understanding interest rates

There is a widespread assumption that interest rates represent the cost of borrowing money. In the narrow sense that it is a cost paid by a borrower, this is true. Monetary policy planners enquire no further. Central bankers then posit that if you reduce the cost of borrowing, that is to say the interest rate, demand for credit increases, and the deployment of that credit in the economy naturally leads to an increase in GDP. Every central planner wishes for consistent growth in GDP, and they seek to achieve it by lowering the cost of borrowing money.

The origin of this approach is strictly mathematical. First published in 1871, William Stanley Jevons in his The Theory of Political Economy was one of the three original proposers of the price theory of marginal utility and became convinced that mathematics was the key to linking the diverse elements of political science into a unified subject. It was therefore natural for him to treat interest rates as the symptom of supply and demand for money when it passes from one hand to another with the promise of future repayment.

Another of the discoverers of the theory of marginal utility was the Austrian Carl Menger, who explained that prices of goods were subjective in the minds of those involved in an exchange. With respect to interest, Menger was the probably the first to argue that as a rule people place a higher value on the possession of goods, compared with possession of them at a later date. Being the medium of exchange, this becomes a feature of money itself, whose possession is also valued more than its possession at a future date. The discounted value of later ownership is reflected in interest rates and is referred to by Mengers’ followers as time preference.

He argued that the level of time preference was fundamentally a human choice and therefore could not be predicted mathematically. This undermines the assumption that interest is simply the cost of money because human preferences drive its evaluation. Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, who followed in Menger’s footsteps saw it from a more capitalistic point of view, that a saver’s money, which was otherwise lifeless, was able to earn the saver a supply of goods through interest earned from it.[iii]

Böhm-Bawerk confirmed that interest produced an income for the capitalist and to an entrepreneur was a cost of borrowing. But he agreed with Menger that the discounted value of time preference was a matter for the saver. Therefore, savers are driven mainly by time-preference, while borrowers mainly by cost. In free markets, this was why borrowers had to bid up interest rates to attract savers into lending instead of consuming.

In those days, it was unquestionably understood that money was only gold, and credible currencies and credit were gold substitutes. That is to say, they circulated backed by gold and were freely exchangeable for it. Gold and its credit substitutes were the agency by which producers turned the fruits of their labour into the goods and services they needed and desired. The role of money and credit was purely temporary. Temporal men valued gold as a good with the special function of being money. And as a good, its actual possession was worth more than just a claim on it in the future. But do they ascribe the same time preference to a fiat currency? To find out we must explore the nature of time preference further as a concept under a gold standard and also in an unanchored currency environment, in order to fully understand the future course of interest rates.

Time-preference in classical economics

Time-preference can be simply defined as the desire to own goods at an earlier date rather than later. Therefore, the future value of possessing a good must stand at a discount compared with actual possession, and the further into the future actual ownership is expected to materialise, the greater the discount. But instead of pricing time preference as if it were a zero-coupon bond, we turn it into an annualised interest equivalent.

Obviously, time preference applies primarily to lenders financing production, which requires the passage of time between commencement and output. Borrowed money must cover partly or in whole the acquisition of raw materials, and all the costs required to make a finished article, and the time taken to deliver it to an end-user for profit.

The easiest way to isolate time-preference is to assume an entrepreneur has to borrow some or all of the financial resources necessary. We now have to consider the position of the lender, who is asked to join in with the sacrifice of his current consumption in favour of its future return. The lender’s motivation is that he has a surplus of money to his immediate needs and instead of just sitting on it, is prepared to deploy it profitably. His reward for doing so is that by providing his savings to a businessman, his return must exceed his personal time-preference.

The medium for matching investment and savings is obviously credit. The financing of production above all else is what credit facilitates. We take this obvious function so much for granted and that interest is seen to be a cost of production that we forget that interest rates are actually set by time-preference.

Intermediation by banks and other financial institutions further conceal from us the link between interest and time-preference, often fuelled by the saver’s false assumption he is not parting with his money by depositing it in a bank.

When a saver saves and an entrepreneur invests, the transaction always involves a lender’s savings being turned into the production of goods and services with the element of time. For the lender, the time preference value for which interest compensates him must always exceed the loss of possession of his capital for a stated period. But with credit anchored to sound money, the level of interest compensation demanded by savers for time preference is strictly limited. The case for fiat currencies is radically different.

Time preference and fiat money

So far, we have considered time preference measured in a currency which is credibly tied to money, legally gold. Under a fiat currency regime, the situation is substantially different because of fiat currency’s instability.

The ubiquity of unbacked state currencies certainly introduces uncertainty over future price stability and the value of credit. Not only is the saver isolated from borrowers through the banking system and often has the misconception that his deposits are still his property (in which case time preference does not apply), but his savings are debased through persistent inflation of the currency. The interest he expects is treated as an inconvenient cost of production, to be minimised. Interest earned is taxed as if it were the profit from a capitalist trade, and not compensation for a temporary loss of possession of his property.

It is not surprising that with the saver regarded as a pariah by Keynesian economists, little attention is paid to time preference. But if savers were to collectively realise the consequences of this injustice, they would demand far higher interest rate compensation for losing possession of their capital. They would seek redress for loss of possession, monetary depreciation, and counterparty risk, all to be added and grossed up for taxes imposed by the state. That will not happen until markets take pricing of everything out of government control.

There is an old adage, that in the struggle between markets and the desires of governments markets always win in the end. It is essential to understand that if the driving forces behind time preference for savers are not satisfied, eventually they will dump their credit liquidity in favour of real money, which is only gold and possibly silver, and for goods that they may need in future. The seventy or so recorded hyperinflations of fiat currencies have demonstrated that when currency and credit lose their credibility, they lose all their purchasing power. As these circumstances unfold, the market response is to drive interest rates and bond yields substantially higher, because time preference is failing to be satisfied. If the authorities resist by suppressing interest rates, the currency simply collapses. And then there is no medium to value financial assets, other than by gold itself.

The consequences of contracting bank credit

So far, this article has only touched on the important role of bank credit in the economy. Bank credit finances virtually all the transactions that in aggregate make up GDP. Banks are now contracting their credit, being dangerously leveraged in the relationship between total assets and balance sheet equity at a time of failing economies.

The consequences for GDP are widely misunderstood. It is commonly assumed that an economic downturn is driven by higher interest rates and their impact on consumer demand. That is putting the cart before the horse. If banks withdraw credit from the economy, it is a mathematical certainty that nominal GDP falls. It is the withdrawal of credit that is responsible for downturns in GDP. It is the rest that follows.

There can be little doubt that with balance sheet leverage averaging over twenty times in the Eurozone and Japan, and with some British banks not far behind, that the global contraction of bank credit will be severe. The effect on less leveraged banking systems, such as that of the US, will be profound due to the international character of modern banking and finance. World-wide, businesses are set to become rapidly insolvent due to credit starvation and bankruptcies will become the order of the day.

Central banks are facing an increasing dilemma, of which the investing public are becoming increasingly aware. Do they intervene with unlimited expansion of their credit to replace contracting commercial bank credit, or do they just stand back and let these distortions wash out? Effectively, it is a choice between undermining their currencies even more or allowing them to stabilise.

They will almost certainly attempt to mitigate the effects of commercial bank credit being withdrawn. Attempts by central banks to control the expansion of their own balance sheets through quantitative tightening will be abandoned, and quantitative easing reintroduced instead. And just as the expansion of commercial bank credit reduces interest rates below where they would normally be, the withdrawal of commercial bank credit tends to increase interest rates, as borrowers struggle to find any available credit. There’s no point in central bankers turning to central bank digital currencies for salvation because there is too little time to introduce them.

Since the 1980s, having moved progressively towards expanding credit for purely financial activities and taking on financial collateral against loans, the contraction of bank credit is bound to have a profound effect on financial markets as well. Collateral will be sold, market-making curtailed, and derivative positions reduced. Driven partly by Basel 3 regulatory requirements, banks will amend their activities to prioritise balance sheet liquidity. Corporate bond holdings will be sold in favour of short-term government treasury bills. Long-term government debt will be sold for shorter maturities.

There can be little doubt that banks contracting credit exposed to financial markets is far easier and quicker than withdrawing credit for GDP-qualifying transactions. And just as the expansion of commercial bank credit for purely financial activities since the 1980s has been substantial, its contraction will not be trivial. The effect on valuations is set to repeat the consequences of bank failures in the Wall Street crash of 1929-32, when the Dow lost 89% of its value.

There is also a symbiotic effect between the contraction of bank credit in the GDP economy and financial markets, with the losses and bankruptcies of the former further depressing confidence in the latter. Unless central banks intervene, it amounts to a perfect storm. But their intervention only serves to destroy the purchasing power of their unbacked currencies, in which case interest rates will rise stratospherically anyway.

Comments on gold’s recent underperformance

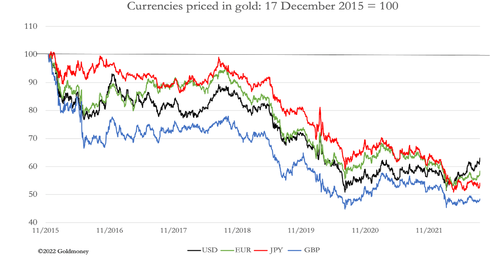

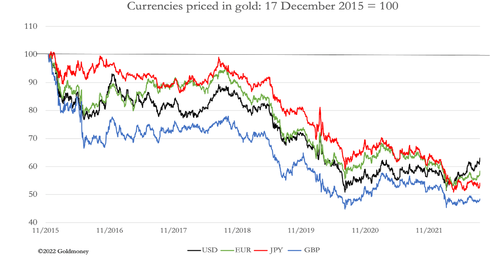

The chart above presents gold as it should be presented, with unstable fiat currencies being priced in real money, which is gold. For technical analysts, the current bear market for these major currencies relative to gold started in mid-December 2015, and the four currencies in the chart have been indexed to that point.

Since then, they have all declined, with sterling down 51.6%, the yen down 45.9%, the euro down 41.6%, and the dollar down 37%. It should be noted that at this stage of the global bear market, sterling, the euro, and yen are seen to be most vulnerable to interest rate rises. Their government bond yields have become marooned at lower levels than equivalent US Treasuries, seen in the fiat world as the riskless investment. The euro and yen face the consequences of interest rates suppressed by the ECB and BOJ respectively into negative territory. Sterling has long suffered from a credibility problem relative to the dollar, and gilts still yield less than US Treasuries.

While the dollar is the least bad currency, nevertheless inflation of the dollar’s total bank credit over time has been dramatic. It was noted above that since 1971, US M3 credit and currency has multiplied 33 times, while the price of gold in dollars has multiplied 38 times. But M3 had already increased from $44.18bn in 1934, when the dollar was devalued from $20.67 an ounce to $35, to $605bn in August 1971 when Bretton Woods was suspended. Including the expansion of M3 from 1934 makes the increase to date 490 times. In other words, gold has yet to discount much of the dollar’s post-depression credit and currency expansion.

In approximate terms we can conclude that the gold-dollar relationship has yet to fully adjust to the dollar’s long-term inflation. In price terms, that gives some comfort to gold bulls, but not too much should be read into the relationship.

More importantly, there is nothing discounted in the dollar gold price for the likely future deterioration of the fiat dollar’s purchasing power. Therefore, we can conclude that as well as being real money and all the rest being credit, gold prices at the current level offer an unrecognised safe haven opportunity for investors unhappy to leave the proceeds of their liquidated portfolios in fiat cash.

Summary and conclusion

It is with great regret that we must admit that the majority of investors who delegate the management of their capital into the hands of professional fund managers and investment advisers are likely to suffer a destruction of wealth that could become almost total. The reason is that these advisers and managers are comprised of a generation which has not experienced how destructive the link between persistent price inflation, rising interest rates, and collapsing financial asset values can be. Furthermore, to fully understand the link and current factors driving interest rates higher is not in their commercial interests.

What happened in the 1970s has been described as stagflation — a portmanteau word suggesting something not understood by mainstream economists today. Looking at their economic models and the assumptions behind them, for them a combination of a stagnant economy and soaring inflation is unexplained. The effect they ignore is that inflation is a transfer of wealth from the private sector to the state, and from savers to the commercial banks and their favoured borrowers. The more the expansion of currency and credit, the greater the transfer of wealth becomes, and the impoverishment of ordinary citizen results.

We are not arguing necessarily that inflation, measured by consumer price indices, will continue into the indefinite future, though a case for that outcome is easily justified. What is being pointed out is that current interest rates and bond yields should be far, far higher. With CPI already increasing in excess of 8% annualised in the US, EU, and UK factors of time preference indicate that interest rates and bond yields should be multiples higher than they are currently.

This article has explained the role of bank credit in the economy. Bank credit finances virtually all the transactions that in aggregate make up GDP and non-qualifying financial activities. Banks are now contracting their credit, being highly leveraged in the relationship between total assets and balance sheet equity. They find themselves exposed to cascading losses in an economic downturn, which risks wiping out their balance sheet equity entirely.

Surely, central banks and their governments will do what they have always done in the past in these circumstances: inflate their currencies, if necessary towards worthlessness. The argument in favour of getting out of financial and currency risks into real money — that is gold — has rarely been more conclusive.