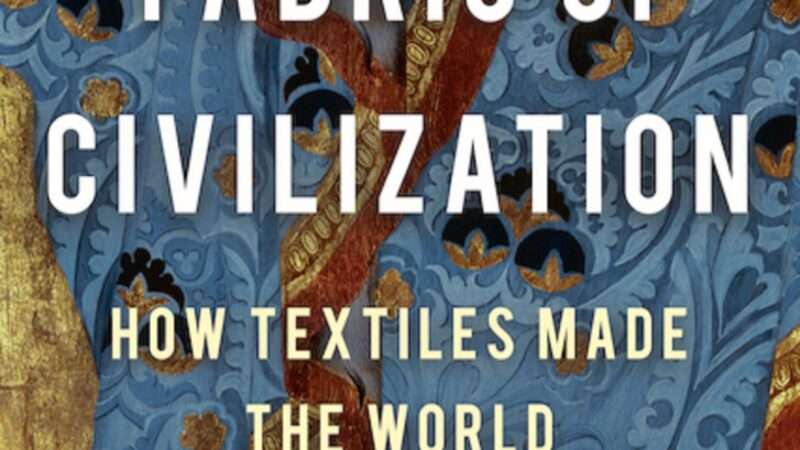

In 1479, a few months shy of his eleventh birthday, Niccolò Machiavelli left the school where he’d learned to read and write and went to study with a teacher named Piero Maria. The future author of The Prince spent the next twenty-two months mastering Hindu-Arabic numerals, arithmetical techniques, and a dizzying assortment of currency and measurement conversions. Mostly he did word problems like these:

If 8 braccia of cloth are worth 11 florins, what are 97 braccia worth?

20 braccia of cloth are worth 3 lire and 42 pounds of pepper are worth 5 lire. How much pepper is equal to 50 braccia of cloth?

One type of problem reflected the era’s shortage of currency. Goods that would sell for one price in coins cost a premium if the buyer paid with other goods. (These problems assume familiarity with trading conventions and therefore present ambiguities to the modern reader.)

Two men want to barter wool for cloth, that is, one has wool and the other has cloth. A canna of cloth is worth 5 lire and in barter it is offered at 6 lire. A hundredweight of wool is worth 32 lire. For what should it be offered in barter?

Two men want to barter wool and cloth. A canna of cloth is worth 6 lire and in barter it is valued at 8 lire. The hundredweight of wool is worth 25 lire and in barter it is offered at such a price that the man with the cloth finds he has earned 10 percent. At what price was the hundredweight of wool offered in barter?

Others were brain teasers dressed up in ostensibly realistic detail.

A merchant was across the sea with his companion and wanted to journey by sea. He came to the port in order to depart and found a ship on which he placed a load of 20 sacks of wool and the other brought a load of 24 sacks. The ship began its voyage and put to sea.

The master of the ship then said: “You must pay me the freight charge for this wool.” And the merchants said: “We don’t have any money, but take a sack of wool from each of us and sell it and pay yourself and give us back the surplus.” The master sold the sacks and paid himself and returned to the merchant who had 20 sacks 8 lire and to the merchant who had 24 sacks 6 lire. Tell me how much each sack sold for and how much freightage was charged to each of the two merchants?

Along with their famed humanist arts and letters, the mercantile cities of early modern Italy fostered a new form of education: schools known as botteghe d’abaco. The phrase literally means “abacus workshops,” but the instruction had nothing to do with counting beads or reckoning boards. To the contrary, a maestro d’abaco, also known as an abacist or abbachista, taught students to calculate with a pen and paper instead of moving counters on a board.

The schools took their misleading name from the Liber Abbaci, or Book of Calculation, published in 1202 by the great mathematician Leonardo of Pisa, better known as Fibonacci. Brought up in North Africa by his father, who represented Pisan merchants in the customs house at Bugia (now Béjaïa, Algeria), the young Leonardo learned how to calculate using the nine Hindu digits and the Arabic zero. He was hooked.

After honing his mathematical skill as he traveled throughout the Mediterranean, Fibonacci eventually returned to Pisa. There he published the book that enthusiastically introduced the number system we use today.

Fibonacci’s novel methods of pen-and-paper reckoning were ideal for Italian textile merchants, who wrote lots of letters and needed permanent account records. Beginning in Florence in the early fourteenth century, specialized teachers began teaching the new system and producing handbooks in the vernacular. Consistent sellers, the books served simultaneously as children’s textbooks, merchants’ reference tools, and, with their brain-teasing puzzles, recreational materials.

From the abacists’ classrooms, future merchants and artisans typically graduated to apprenticeships and work. But a grounding in commercial math was also common for those like Machiavelli, who were destined for higher education and a career of statesmanship and letters. In a society based on trade, cultural literacy included calculation.

As they drilled generations of children on how to convert hundredweights of wool into braccia of cloth or to allocate the profits from a business venture to its unequal investors, the abacists invented the multiplication and division techniques we still use today. They made small but important advances in algebra, a subject universities scorned as too mercantile, and devised solutions to common practical problems. On the side, they did consulting, mostly for construction projects. They were the first Europeans to make a living entirely from math.

In his seminal 1976 study of nearly 200 abacus manuscripts and books, historian of mathematics Warren Van Egmond emphasizes their practicality—a significant departure from the classical view of mathematics, inherited from the Greeks, as the study of abstract logic and ideal forms. The abacus books treat math as useful.

“When they study arithmetic,” he writes, “it is to learn how to figure prices, compute interest, and calculate profits; when they study geometry it is to learn how to measure buildings and calculate areas and distances; when they study astronomy it is to learn how to make a calendar or determine holidays.” Most of the price problems, he observes, concern textiles.

Compared to scholastic geometry, the abacus manuscripts, with their problems about trading cloth for pepper, are indeed down to earth. But they don’t scorn abstraction. Rather, they wed abstract expression to the physical world. The transition from physical counters to pen-and-ink numerals is in fact a movement toward abstraction. Symbols on a page represent bags of silver or bolts of cloth and the relationships between them.

Students learn to ask the question, How do I express this practical problem in numbers and unknowns? How do I better identify the world’s patterns—the flow of money in and out of a business, the relative values of cloth, fiber, and dyes, the advantages and disadvantages of barter over cash—by turning them into math? Mathematics, the abacists taught their pupils, can model the real world. It does not exist in a separate realm. It is useful knowledge.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3lCF8wq

via IFTTT