Last night Fox News host Tucker Carlson vigorously defended qualified immunity, the doctrine that allows public officials to avoid federal civil rights lawsuits if the way they violated your rights has not been outlined with exacting detail in previous case law.

Carlson offered an alternative definition for his viewers. “Qualified immunity means that cops can’t be personally sued when they accidentally violate people’s rights while conducting their duties,” he said. “They can be sued personally when they do it intentionally, and they often are.”

There are a few problems with the statement, the largest being that it is not true.

Qualified immunity provides no distinction between accidental and intentional rights violations. A quick review of previous qualified immunity rulings proves as much. Consider the cops in Fresno, California, who were granted qualified immunity after allegedly stealing $225,000 while carrying out a search warrant.

It was not an accidental robbery, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit acknowledged as much in their ruling last September. Though “the City Officers ought to have recognized that the alleged theft was morally wrong,” the unanimous panel wrote, it concluded that they “did not have clear notice that it violated the Fourth Amendment.” They both received qualified immunity.

Translation: The officers should’ve known that stealing from someone is morally and legally indefensible. But without a court precedent spelling that out for them, the two were off the hook, leaving the plaintiffs no recourse. That is how qualified immunity works in practice.

“Civil immunity has precisely nothing to do with anything that happened in the George Floyd case,” Carlson continued. “Just in case you were wondering, that cop is in jail.”

Again, that represents a fundamental misunderstanding around where and when qualified immunity applies. The doctrine solely pertains to civil liability—a public official who breaks the law and is awarded qualified immunity is not protected from criminal prosecution. The two are entirely unrelated, although it’s worth noting that state prosecutors often decline to bring such charges in the first place.

Put more plainly, former police officer Derek Chauvin may indeed receive qualified immunity from any civil suit brought by the family of George Floyd—the unarmed man who died after Chauvin dug his knee into Floyd’s neck for almost 9 minutes—even if Chauvin’s trial yields a murder conviction.

Carlson continued:

Qualified immunity has worked so well because police officers, maybe more than anyone else in society, must make difficult split-second decisions on the job, and a lot. They do it constantly. Whether to arrest someone, whether to conduct a search, whether to use force against a suspect. Sometimes, actions they sincerely and reasonably believe are legal are found later by courts to be unconstitutional. Sometimes the very laws they enforce are struck down. That’s not their fault, obviously, but without qualified immunity, police could be sued for that personally. They could be bankrupted they could lose their homes. That’s unfair. It would also end law enforcement. No one would serve as a police officer.

There’s quite a bit to unpack there. First, as Institute for Justice attorney Patrick Jaicomo notes, qualified immunity has nothing to do with reaction times but “is about whether the right that was violated was ‘clearly established.'” That standard was established by the Supreme Court in Harlow v. Fitzgerald (1982) in spite of Section 1983 of Title 42 of the U.S. Code, the statute that previously allowed the American public to sue for violations of their constitutional rights. It’s the epitome of the high court legislating from the bench, something conservatives typically oppose.

But perhaps Carlson’s most significant misinterpretation is his claim that cops are only caught in compromising situations when they “sincerely and reasonably” believed their misconduct was both legal and constitutional. Such a claim can only be explained by a lack of familiarity with qualified immunity case law. Take the cop who received qualified immunity after shooting a 10-year-old while in pursuit of a suspect that had no relationship to the child. The officer, sheriff’s deputy Matthew Vickers, was aiming at the boy’s nonthreatening dog.

There were also the cops who were granted qualified immunity after assaulting and arresting a man for standing outside of his own house. And the prison guards who locked a naked inmate in a cell filled with raw sewage and “massive amounts” of human feces. And the cop who, without warning, shot a 15-year-old who was on his way to school. And the cops who received qualified immunity after siccing a police dog on a person who’d surrendered. It doesn’t take much thought to conclude that such courses of action were morally bankrupt.

Then there’s the notion that police officers would lose their homes and leave the force in droves should qualified immunity meet its demise. Puzzlingly, that claim hinges on the assumption that a slew of officers would lose their cases—a tacit acknowledgement that police culture needs to change.

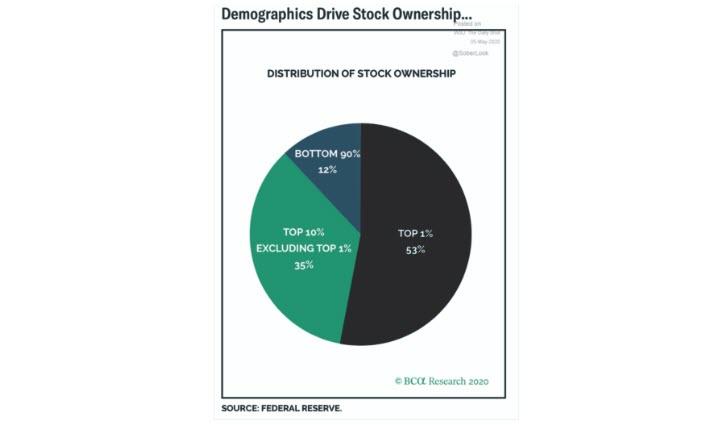

But even so, cops themselves are almost never on the hook for the bill. Cities are. It’s certainly still not an ideal solution for taxpayers, but until police departments can grapple with reform, it’s an option that should be available for those who have their rights flagrantly violated by those that swear to protect and serve.

Incidentally, qualified immunity does not apply only to those who take that oath. It applies to all public officials. That includes, for instance, university administrators who have infringed on students’ due process rights. Carlson has been beating the campus culture war drum for a while. I assume he would not support qualified immunity in those cases, though one wonders if he knows it applies.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3eDNiCj

via IFTTT