Banks Slash Credit Card Limits As Economic Crisis Not Over

Tyler Durden

Tue, 07/28/2020 – 18:15

While the Federal Reserve and the Trump administration plow trillions of dollars into corporate America, buying investment-grade bonds and rocketing the stock market to new highs, there’s a much different story playing out of economic hardships for the everyday American.

There’s a massive pullback by credit card issuers at the moment, reducing credit limits and canceling accounts of consumers.

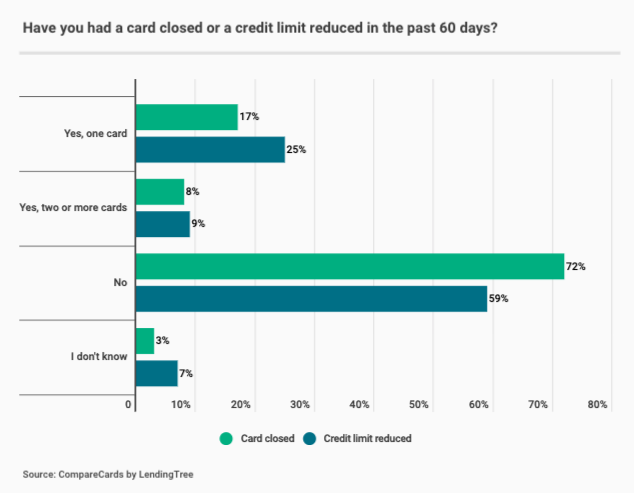

CompareCards’ new survey shows the economic fallout from the virus-induced recession is far from over. About 25% of Americans with credit cards had an account involuntarily canceled between mid-May to mid-July, while 33% said card companies slashed their credit limit.

About 70 million people – more than one-third of credit cardholders – said they involuntarily had a credit limit reduced or a credit card account closed altogether in a 60-day period stretching from mid-May to mid-July.

The report is a clear sign that credit card issuers are still closing cards and reducing credit limits on cardholders in huge numbers, months after an April 2020 CompareCards survey showed that nearly 50 million cardholders had a card closed or credit limit reduced in the first month in which the coronavirus pandemic took hold of the country. – CompareCards

Matt Schulz, the chief industry analyst at CompareCards, told Yahoo Money that “an awful lot of Americans had one of their financial security nets taken out from under them in one of the most difficult economic times in American history.”

The pullback by credit card companies was last seen during the Great Recession when about 16% of cardholders saw limits reduced and accounts involuntarily closed.

“This is, in a lot of ways, a much bigger issue today than it was in the Great Recession,” Schulz said. “It makes sense that banks are taking an even harder line with lending because there’s so much that they don’t know, and they’re so nervous about risk.”

The key takeaway from the survey is that card closures and credit limit reductions continue through summer, even though the Trump administration promotes a ‘rocket ship recovery’ in the economy.

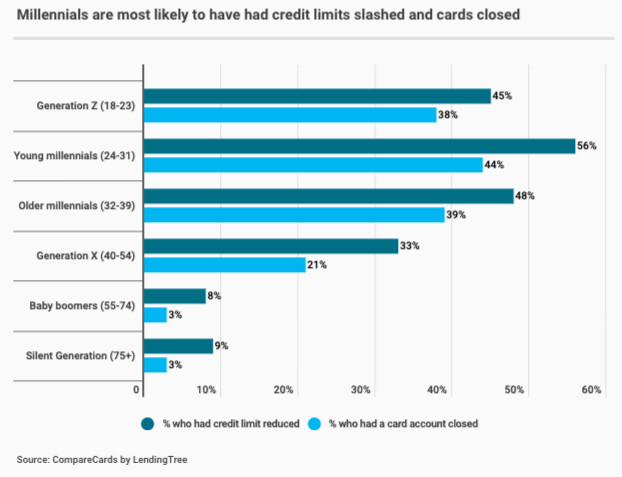

Millennial generation have had the most credit limits slashed and cards closed.

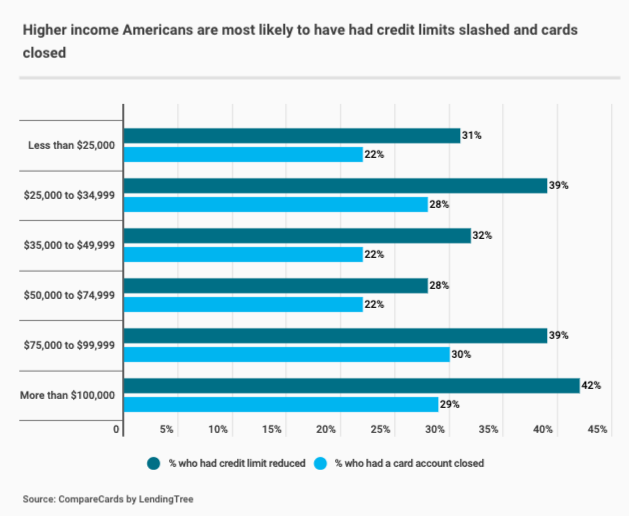

Even folks making over $100,000 have seen limits reduced and cards closed.

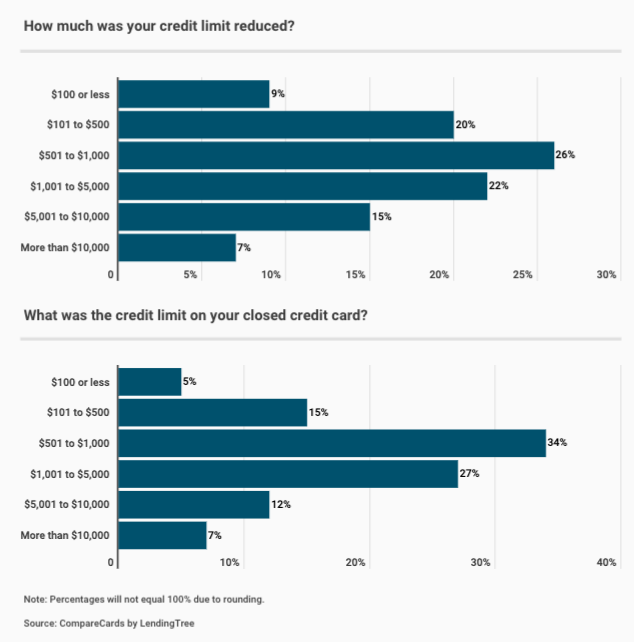

Most of the credit limit reductions weren’t huge.

This all suggest that credit card companies don’t trust consumers and are preparing for the next downturn that will pressure households once more. With a fiscal cliff looming, and if the next round of stimulus isn’t passed quickly, another credit crunch for the bottom 90% of Americans could be just ahead.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/305cIDZ Tyler Durden