Almost a year to the day that Louisville police officers killed Breonna Taylor during a no-knock raid, the Kentucky Senate passed a bill which makes it a crime to insult and taunt cops. If S.B. 211 becomes law, you could get up to three months in jail and a $250 fine if you flip off the fuzz in a way “that would have a direct tendency to provoke a violent response from the perspective of a reasonable and prudent person.”

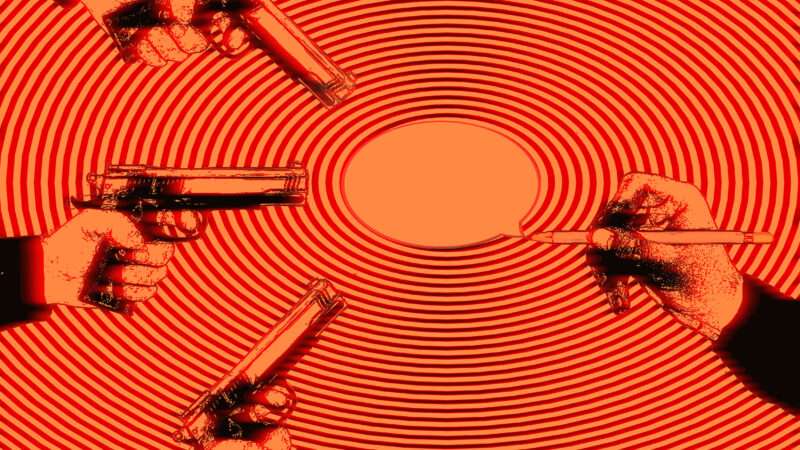

It’s just one example of a slew of proposed new laws that are chilling free speech. While freethinkers are rightly worried that private online platforms such as Amazon, Twitter, and Facebook are increasingly—and often arbitrarily—cracking down on speech for political reasons, the much graver threat comes from governments at all levels seeking to ban or compel speech.

If Amazon won’t stock your book, you can still hawk it at Barnes & Noble or on your own site, but when the government says no, there’s nowhere else to go.

Earlier this year, lawmakers in Kentucky also introduced legislation that “would make a user entitled to damages if a social media platform deletes or ‘censors’ religious or political posts.” Conservatives who rightly yelled bloody murder when Christian bakers were forced to make cakes for same-sex weddings are now trying to stop social media platforms from running their businesses the way they see fit.

In Florida, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis has proposed legislation that would ban Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms from suspending the accounts of political candidates. They would face fines of up to $100,000 a day and the new law would also allow regular users to sue platforms for damages if they feel they’ve been treated unfairly.

Similar legislation has been proposed in Oklahoma, North Dakota, and Texas, where Republican Gov. Greg Abbott has said, without citing actual evidence, that conservative viewpoints are being systematically silenced. “Pretty soon,” he promises, such supposed censorship is “going to be against the law in the state of Texas.” That law, S.B. 12, is poised to pass the state Senate.

Back in the pre-internet days, you could count on conservative Republicans to scream about the need to regulate sex and drugs on TV and in music but these days they seem to want social media companies to do no moderating of content. So maybe that’s progress.

At the same time, liberal Democrats, who themselves used to scream about violent video games, are pushing for more regulation of speech they don’t like. In Colorado, a proposed law would create a “digital communications commission” that would investigate platforms to make sure they don’t allow “hate speech,” “undermine election integrity,” or “disseminate intentional disinformation, conspiracy theories, or fake news”—all exceptionally vague terms that aren’t even defined in the legislation. The commission would have the ability to order changes in the way platforms operate.

At the national level, two congressional Democrats—Rep. Anna Eshoo (D–Calif.) and Rep. Jerry McNerney (D–Calif.)—have sent letters to the heads of Comcast, Verizon, Dish, and other cable and satellite companies demanding to know why such private services carry Fox News, Newsmax, and other supposed purveyors of “misinformation.” As Reason’s Robby Soave put it, the letter “was an act of intimidation.” It’s a rare week when high-wattage politicians such as Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) or Sen. Ted Cruz (R–Texas) don’t threaten Big Tech with some sort of reprimand because they don’t like what’s popular on Facebook or Twitter.

The good news is that laws seeking to control individuals and platforms are blatantly unconstitutional because they compel the speech of private actors and because Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act allows broad discretion in running websites and platforms. When challenged in court, they’ll almost certainly be struck down.

The bad news is that the laws just keep coming, because politicians of all stripes want to control speech in a way that favors their agendas and they don’t care about whether a law respects the First Amendment.

We should loudly criticize platforms for kicking people off in arbitrary ways that diminish our ability to freely argue and disagree about politics and culture. We want more participation, not less. But it’s even more important to recognize private citizens’ and businesses’ right to freely associate with whomever they want.

I find it disturbing as hell that a member of the band Mumford & Sons felt compelled to cancel himself for the “pain he caused” after saying he liked a book by the controversial journalist Andy Ngo. I’m deeply bothered that eBay has delisted old copies of Dr. Seuss books and that Amazon, which once aspired to sell every book in print, sees fit to drop titles that rub some activists the wrong way. I’m outraged that Twitter and Facebook banned Donald Trump essentially for being an asshole.

But far worse than such private cancel culture is when politicians tell us we don’t have a right to insult cops, or when they’re the ones setting the rules about what we must prohibit—or allow. That way madness lies and it makes the online outrage of the day look absolutely trivial by comparison.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3c0CXRN

via IFTTT