In two previous posts here and here, Josh Blackman and I contended that Judge O’Connor’s conclusion that the individual insurance mandate is unconstitutional is correct. In our view, the Supreme Court already reached this conclusion in 2012. We also contended that his analysis of standing is supported by Part III.A of Chief Justice Roberts’s controlling opinion–even if that opinion is in tension with questions asked during oral argument.

But even if Judge O’Connor is correct about both of these two issues, the third remaining issue is still dispositive: Was Judge O’Connor correct to conclude that the unconstitutional insurance mandate is inseverable from the ACA as a whole, which must as a result also fall? Speaking solely for myself now, because the law of severability (such as it is) is not my area of expertise, I am more hesitant to offer a definitive opinion on this question.

On the one hand, Congress declined to include a standard “severability clause” in the ACA. Under current doctrine, the failure to do so requires the courts to answer a difficult counterfactual question: was the unconstitutional provision so essential to the remainder of the Act that Congress would not have enacted the entire statute without the unconstitutional provision.

During the ACA litigation, the legal team for NFIB (of which I was a member) contended that the individual insurance mandate was expressly deemed by both Congress and the government to be essential to its broader regulatory scheme. To appreciate why, we need to understand the reasoning of the decision in the case I argued in the Supreme Court: Gonzales v. Raich (2005).

In Raich, the Court held that the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) could constitutionally be applied to the wholly intrastate possession of state-regulated medical marijuana because this activity was “economic” in nature according to a 1966 Websters dictionary definition of “economics.” But the Court in Raich then offered a secondary rationale it found in dictum in U.S. v. Lopez: Congress can regulate even noneconomic activity if doing so is essential to the broader regulation of interstate commerce.

In NFIB, both Congress and the executive branch contended that the mandate was constitutional under this secondary rationale of Raich because the individual insurance mandate was “essential” to the ACA’s broader regulation of interstate commerce. Indeed, Congress included in the statute itself detailed findings about how the mandate was “essential” and concluded:

The [insurance purchase] requirement is an essential part of this larger regulation of economic activity, and the absence of the requirement would undercut Federal regulation of the health insurance market. (Emphases added.)

The statute also stated:

The requirement is essential to creating effective health insurance markets that do not require underwriting and eliminate its associated administrative costs. (Emphasis added.)

This conclusion came after numerous findings explained exactly how the mandate functions within the ACA’s overall scheme.

Why were these findings worded this way? Clearly, this was done to satisfy the secondary rationale of Gonzales v. Raich. That case held that, under Congress’s Necessary and Proper Clause power, it could regulate local noneconomic activity if doing so was an

essential part of a larger regulation of economic activity, in which the regulatory scheme could be undercut unless the intrastate activity were regulated. (Emphases added.)

In other words, if Congress could not enact the individual mandate, the ACA’s other components–such as guaranteed issue and community rating, “could be undercut.” Here is how Judge O’Connor summarized the Congressional findings:

All told, Congress stated three separate times that the Individual Mandate is essential to the ACA. That is once, twice, three times and plainly. It also stated the absence of the Individual Mandate would “undercut” its “regulation of the health insurance market.” Thirteen different times, Congress explained how the Individual Mandate stood as the keystone of the ACA. And six times, Congress explained it was not just the Individual Mandate, but the Individual Mandate “together with the other provisions” that allowed the ACA to function as Congress intended.

But these Congressional findings offered to justify the constitutionality of the individual mandate under Raich also had unavoidable implications for the severability of the mandate from he rest of the ACA–implications the government largely conceded during the NFIB litigation.

If we accept this emphatic assessment by Congress of how essential the mandate is to the operation of the broader regulatory scheme as definitive evidence of its “intent”–as seems compelling to do–then, under established severability doctrine, the mandate was inseverable. The Congress that enacted the ACA would not have done so without the individual mandate because it was essential to the broader scheme. In NFIB, even the Obama administration agreed that the individual insurance mandate was inseverable from the guaranteed issue and community ratings provisions of the Act. The rest of the ACA, the Solicitor General concluded, could be severed.

Given that the ACA lacked a severability clause, current severability doctrine (as I understand it) requires courts to ascertain whether the Congress that enacted the law would have thought the individual mandate to be essential to its entire scheme. If current doctrine adopts this time frame, then the fact Congress deemed the mandate to be essential in 2010 does not change with the passage of time or experience. That the mandate was deemed to be essential by the enacting Congress is as true today as it was in 2010 when Congress passed the ACA and in 2012 when we argued this in NFIB.

On the other hand, the different and later Congress that passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), which zeroed out the penalty enforcing the insurance requirement, did not seem to consider the penalty essential to the rest of the ACA it left standing. Should the courts look instead to this judgment by Congress to assess severability? Or should the courts look to the intent of the Congress that enacted the ACA? On this issue, I retain an open mind.

Judge O’Connor’s severability analysis–including his discussion of the intentions of both the 2010 and 2017 Congress–seems compelling to me. It seems to me that the correct time frame is that of the enacting Congress–whose intent on the question of whether the mandate was essential to the broader scheme was made explicit. And I am therefore inclined to favor our original position on severability. (Judge O’Connor also persuasively explains why the intent of the 2017 Congress using its reconciliation procedures did not differ from that of the enacting Congress.)

But I can also appreciate why this conventional approach to severability now seems counter-intuitive under these circumstances. Perhaps if I had more expertise on severability doctrine–and a firmer grasp of its underlying theory–I would be as sure of Judge O’Connor’s severability analysis as I am of his analysis of the mandate. Or perhaps I am wrong about how existing severability doctrine works. Or perhaps severability doctrine needs to be modified in a circumstance such as this. Or perhaps, per Justice Thomas, a modern severability doctrine should be repudiated.

As the litigation ensues, and I hear more from both sides, my opinion on severability may become more firm than it now is. But what I have heard so far from critics of his decision has not yet persuaded me that Judge O’Connor’s decision on severability is wrong. Indeed, for what it’s worth, I find it persuasive.

Perhaps the ACA champions’ antipathy for this challenge is coloring their views of severability just as my sympathy for the challenge may be coloring mine. Not being a judge tasked with resolving this case, however, I can afford to reserve my own final opinion on the merits of this argument. At least for now.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2L7OouP

via IFTTT

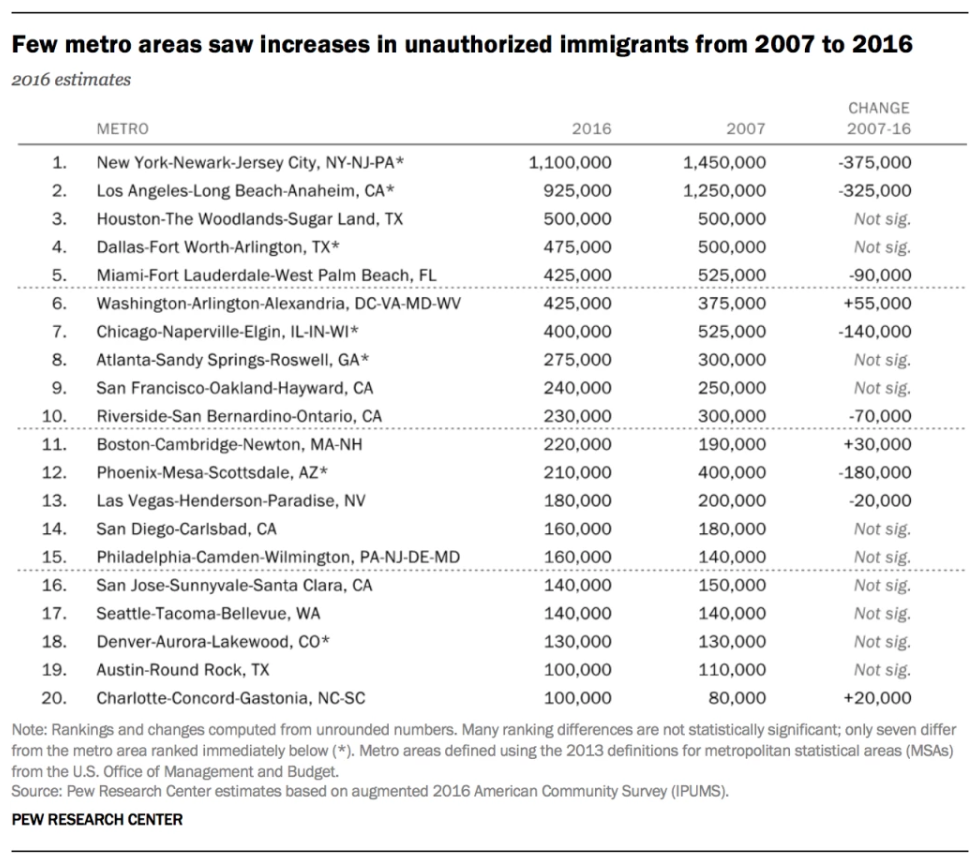

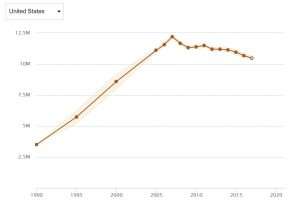

If that’s the big fear, Republicans should take a couple of deep breaths. The number of illegal immigrants has been declining, and it is at its lowest point in about a dozen years. According to

If that’s the big fear, Republicans should take a couple of deep breaths. The number of illegal immigrants has been declining, and it is at its lowest point in about a dozen years. According to