Plaintiffs first argue that the Governor’s orders amount to unconstitutional restrictions on their rights to free speech and assembly…. [T]o support their argument that the orders “are content-based restrictions on constitutionally protected liberties,” Plaintiffs appear to mischaracterize the Commonwealth’s prohibition on gatherings.

The order in question states in no uncertain terms that “[a]ll mass gatherings are hereby prohibited.” This prohibition applies not only to faith-based gatherings, but to “any event or convening that brings together groups of individuals, including, but not limited to, community, civic, public, leisure, … or sporting events; parades; concerts; festivals; conventions; fundraisers; and similar activities.” The “19 categories of businesses” allowed by subsequent order to continue operating are not, as Plaintiffs repeatedly suggest, exceptions to the prohibition on mass gatherings. Rather, by the plain terms of the March 19 Order, “[a]ll mass gatherings are … prohibited.”

Plaintiffs seek to compare in-person attendance at church services with presence at a liquor store or “supercenter store[].” The latter, however, is a singular and transitory experience: individuals enter the store at various times to purchase various items; they move around the store individually—subject to strict social-distancing guidelines set out by state and federal health authorities—and they leave when they have achieved their purpose. Plaintiffs’ desired church service, in contrast, is by design a communal experience, one for which a large group of individuals come together at the same time in the same place for the same purpose.

A more apt comparison, then, is a restaurant or entertainment venue—where patrons are gathered simultaneously for a longer period of time to eat and socialize—or a movie, concert, or sporting event, where individuals come together in a group in the same place at the same time for a common experience. And all such activities are temporarily prohibited.

Similarly unpersuasive is Plaintiffs’ contention that the orders violate their right to freely exercise their religion by discriminating against religious conduct. Again, the order temporarily prohibits “[a]ll mass gatherings,” not merely religious gatherings. Religious expression is not singled out. And further, contrary to Plaintiffs’ assertions, there are no identified exceptions to the prohibition on mass gatherings [such as for liquor, warehouse, and supercenter stores]. {In service of their argument, Plaintiffs make liberal use of the term “gather.” Merriam-Webster defines “gather” as “to come together in a body”; a “gathering” is an “assembly” or “meeting.” These terms do not, as generally understood, encompass separate, uncoordinated shopping trips by unrelated individuals. Presumably, no coordinated gathering in a grocery or liquor store would be permitted under the temporary restrictions.}

Finally, to the extent Plaintiffs argue that the orders violate the Kentucky Religious Freedom Restoration Act by substantially burdening the exercise of their sincerely held religious beliefs, the Court finds, based on the materials submitted by Plaintiffs, that the Governor will likely be able to meet the Act’s requirement of “clear and convincing evidence that [the government] has a compelling governmental interest in” the restrictions “and has used the least restrictive means to further that interest.” Plaintiffs do not contend that the Commonwealth lacks a compelling governmental interest in restricting mass gatherings to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

As to whether the Commonwealth has employed “the least restrictive means to further that interest,” Plaintiffs merely point to orders issued in other states that declared religious gatherings exempt from mass-gathering prohibitions. They offer no evidence that such exemptions are equally effective in preventing the spread of the disease. Given that COVID-19 is widely understood to be transmitted through person-to-person contact, including persons with and without symptoms of illness, Beshear will likely be able to demonstrate that restricting large in-person gatherings is the least restrictive means of accomplishing the Commonwealth’s objective.

This case is primarily about two executive orders that Governor Beshear issued in response to the current Covid-19 pandemic. Together, these two orders amount to an outright ban on traditional, in-person religious services of any kind.

The first order, issued on March 19, prohibits “[a]ll mass gatherings.” Unlike other states adopting similar measures, “mass gathering” is not defined. Rather, Governor Beshear vaguely describes the scope of his order as “includ[ing] any event or convening that brings together groups of individuals, including, but not limited to, community, civic, public, leisure, faith-based, or sporting events; parades; concerts; festivals; conventions; fundraisers; and similar activities.” The broad sweep of this prohibition is undeniable: It applies to gatherings of any number of people. It applies to gatherings in confined spaces as well as the outdoors. It applies to gatherings in which people remain 6 feet apart, and it applies to gatherings in which people drive up and never leave their cars. This order is written as broadly as possible, and it leaves no doubt that all “faith-based” gatherings are illegal.

That’s not to say, however, that the order is without exception. It in fact contains two. First, the order states that “a mass gathering does not include normal operations at airports, bus and train stations, medical facilities, libraries, shopping malls and centers, or other spaces where persons may be in transit.” Second, the order provides that a mass gathering “does not include typical office environments, factories, or retail or grocery stores where large numbers of people are present, but maintain appropriate social distancing.” Religious activities are not included in either exemption.

Six days after prohibiting the vaguely-defined-but-broadly-applicable “mass gatherings,” Governor Beshear issued an executive order closing all organizations that are not “life-sustaining.” “Life-sustaining” is defined in the order as any organization “that allow[s] Kentuckians to remain Healthy at Home.” It includes approximately 19 different categories of businesses and organizations. Religious organizations are not among them.

What does Governor Beshear consider life-sustaining? “Media,” is one example, which he defines as, “Newspapers, television, radio, and other media services.” Also included on the list are law firms, accounting services, real estate companies, liquor stores, and hardware stores.

The lone reference to religious organizations in the March 25 order allows for religious charities to continue operating to the extent that they “provid[e] food, shelter, and social services, and other necessities of life for economically disadvantaged or special populations, individuals who need assistance as a result of this emergency, and people with disabilities.” So while the order does not permit religious organizations to provide religious services to their parishioners and members, it does allow them to provide the kinds of services that the Governor has pre-approved.

Together, the March 19 and March 25 orders impose a sweeping prohibition against religious activity throughout every corner of the Commonwealth. Even though these same orders broadly permit individuals to crowd into hardware stores and law offices, or newsrooms, liquor stores and grocery stores, they do not permit people to attend religious services at a church, mosque, synagogue, or other house of worship, even if they follow social-distancing guidelines. This is, without question, an unconstitutional targeting of religious activity.

The Court mistakenly found that the executive orders do not target religious conduct because “[r]eligious expression is not singled out.” It went on to state that “there are no identified exceptions to the prohibition on mass gatherings.” This is, respectfully, not accurate. As explained above, the mass-gathering ban permits gatherings in airports, grocery stories, office spaces, and other places “where large numbers of people are present.”

Only wordplay allows one to reach a different conclusion. The Court explained that to “gather” ordinarily means “to come together in a body,” and that a “gathering” is an “assembly” or “meeting.” So, the Court reasoned, “uncoordinated shopping trips by unrelated individuals” at a grocery store or liquor mart do not qualify.

That conclusion, however, overlooks a significant carve-out from the March 19 order. The order permits people to continue their daily routine in “typical office environments,” which surely includes “meetings” as the Court explains it. In a “typical office,” employees show up together, working for a common purpose during similar hours and often in close proximity. It is exactly the kind of coordinated activity that the Court says is a prohibited mass gathering. Yet the March 19 expressly exempts “typical office environments” from its coverage, while simultaneously singling out “faith-based” activities for no such exemption.

“If the law appears to be neutral and generally applicable on its face, but in practice is riddled with exemptions … the law satisfies the First Amendment only if it advances interests of the highest order and is narrowly tailored in pursuit of those interests.” Said another way, even orders that appear facially neutral are not treated as such when they are filled with exemptions for secular activities. Governor Beshear’s orders single out faith-based activities for prohibition, while simultaneously allowing similarly risky secular activities to continue. This is quintessential discrimination against religion requiring the state to meet the high burden of strict scrutiny.

Just as troubling is Governor Beshear’s refusal to define religious activity as “life-sustaining” for those Kentuckians with sincerely held beliefs about communal worship. Not every state has taken the same discriminatory path. Ohio, a state that has also implemented aggressive social-distancing protocols and shelter-in-place orders, recognized the danger in categorizing some activities as essential but excluding religion from that list …. Governor Beshear issued a similar order three days later, when he set out the 19 differentcategoriesof”life-sustaining”businessesthatcanremainopen.Whilemuch of the wording is the same, Governor Beshear excluded religious organizations from the list of permissibleactivity ….

The exclusion of religious organizations from the list of “life-sustaining” activities is no small matter. Governor Beshear has publicly declared that attending worship service is not life-sustaining, while allowing liquor stores and retailers to continue operating. It is mind-boggling discrimination. Or as the court noted in a similar case, “if beer is ‘essential,’ so is Easter.” On Fire Christian Ctr., 2020 WL 1820249, at *7. The fact that Governor Beshear has identified 19 categories of activities that are, in his judgment, more essential than in-person church services is proof positive of impermissible targeting of religious exercise.

{Nor does it lessen the discriminatory sting that Governor Beshear has recommended Kentuckians attend virtual services as an alternative. With respect, the point of the First Amendment is that Governor Beshear does not get to decide whether a virtual gathering is sufficient for every person of every faith. On this issue, Governor Beshear has gone remarkably far in dictating how Kentuckians should exercise their religion. At his Good Friday daily press conference, the Governor chastised people about what a true “test of faith” is. He proclaimed: “It is not a test of faith in whether you’re going to an in-person service, it’s a test of faith that you’re willing to sacrifice to protect your fellow man, your fellow woman, your fellow Kentuckian, and your fellow American.” Yet the First Amendment exists precisely to protect the beliefs of those who disagree.}

The thrust of the March 19 and March 25 orders are clear: Despite the First Amendment and Kentucky’s own uniquely strong protections for religious liberty, Governor Beshear has failed to adopt neutral or generally applicable laws to address the current crisis, instead choosing to target religious organizations for disfavored treatment. It is, “‘beyond all reason,’ unconstitutional.” On Fire Christian Ctr., 2020 WL 1820249, at *2 (quoting Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11, 31 (1905)).

[II.] The ban on religious worship is not narrowly tailored….

The First Amendment prohibits the government from burdening one’s “free exercise” of religion…. In practice, that means the government cannot implement laws “targeting religious beliefs as such.” But it also means that “[o]fficial action that targets religious conduct for distinctive treatment cannot be shielded by mere compliance with the requirement of facial neutrality.” Public officials, in other words, cannot target religion through selective enforcement of otherwise neutral laws. Rather, laws must be neutral and generally applicable in both text and reality to survive constitutional scrutiny. And “[a] law that targets religious conduct for distinctive treatment or advances legitimate governmental interests only against conduct with a religious motivation will survive strict scrutiny only in rare cases.”

No one doubts that the government has a compelling interest in preventing the spread of Covid-19 during the current pandemic. But so far, Governor Beshear has offered no explanation as to why it is necessary to prohibit religious activities that pose exactly the same risk as similar, non-religious activities. And in denying the Plaintiffs a temporary restraining order, this Court never even addressed the issue. Instead, the Court reasoned in a conclusory fashion that the Governor was likely to prevail in his assessment that the broad, ill-defined prohibitions against all religious gatherings are the least-restrictive means of prohibiting the spread of Covid-19. That is, at best, highly implausible.

The error here is most pronounced in the Court’s assessment of what it means to “gather.” As the Court explains it, a “gathering” is distinct from an “uncoordinated shopping trip[] by unrelated individuals.” But presumably, the coronavirus does not care about whether people are “coordinating” or not. And it does not care whether they are in a store as friends, neighbors, or individuals. Rather, as the Court explained, Covid-19 “is widely understood to be transmitted through person-to-person contact,” regardless of whether those people came into contact in a “meeting” or in a grocery aisle. So the obvious, least-restrictive means of preventing the spread of Covid-19 is not to target the purpose for which people come into close contact, as Governor Beshear’s March 19 order does, but to target the close contact itself. By simply implementing the same social-distancing measures for religious gatherings as for liquor stores, retail chains, and offices, the Governor could achieve the same state interest in a less-restrictive manner.

In fact, the Court’s decision implicitly reveals just how imprecise and overbroad the March 19 order is. The Court held that “Beshear will likely be able to demonstrate that restricting large in-person gatherings is the least restrictive means of accomplishing the Commonwealth’s objective.” But the word “large” is nowhere to be found in the March 19 order’s definition of “mass gathering.” The term is used in defining one of the exemptions—”office environments … where large numbers of people are present.”

So in finding that Governor Beshear’s order is the least-restrictive means, the Court actually showed that there are additional ways in which Governor Beshear could restrict his order further. Presumably, for example, the order could permit small gatherings, or gatherings based upon the size of the space in which people meet. Could a congregation of ten individuals, for example, meet for worship in a large auditorium? Surely this would pose no more serious risk of transmitting the virus than an office where “large numbers of people are present.” But under the March 19 order, it is impermissible.

Moreover, there is ample evidence to suggest that broadly banning church services is not the least restrictive way of preventing further danger from Covid-19. Tennessee, for example, has not closed its places of worship. Yet Kentucky’s hospitalization rate for Covid-19 is more than twice that of Tennessee’s, and Tennessee has had 40 percent fewer deaths per capita. And to this date, Governor Beshear has failed to offer any evidence of any kind that closing religious services is more effective than mandatory strict social distancing.

And on the point of geography, Governor Beshear’s orders face other problems as well. Governor Beshear has insisted on maintaining a statewide lockdown that does not take into account varying infection rates in different places. Currently, there are 8 counties in Kentucky that have zero reported cases and another 56 counties that have between one and ten. While residents of Jefferson County are free to continue shopping at big box retailers and grocery stores, where they might run into countless strangers as they turn the corner of an aisle, residents in Harlan where there are no reported cases are forbidden from attending church on Sunday. It defies logic to label this as the least-restrictive means of stopping the spread of Covid-19.

Nor can Governor Beshear find support in Jacobson v. Massachusetts. Even under Jacobson, a law is invalid if “purporting to have been enacted to protect the public health, the public morals, or the public safety, [the law] has no real or substantial relation to those objects, or is, beyond all question, a plain, palpable invasion of rights secured by the fundamental law.” That is precisely the problem with Governor Beshear’s executive orders here. Singling out religious activity for disfavored treatment is the kind of “palpable invasion of rights” that even a pandemic cannot justify. On Fire Christian Ctr., 2020 WL 1820249, at *8 n.73.

[III.] Constitutional requirements aside, the Kentucky Religious Freedom Restoration Act requires enjoining the Governor’s orders.

Kentucky law could not be more clear: “Government shall not substantially burden a person’s freedom of religion.” “Burden” is defined to include “indirect burdens such as withholding benefits, assessing penalties, or an exclusion from programs or access to facilities.” There is no question that the worshippers of Maryville Baptist Church have been assessed a penalty due to their exercise of sincerely held religious beliefs—they were, after all, ordered to quarantine. There is also no question that the Governor’s orders burden “access” to the facilities of Maryville Baptist Church—the Governor has, after all, ordered that no one attend service at the church.

The question, then, is whether the Governor is likely to prove “by clear and convincing evidence that it has a compelling governmental interest in infringing the specific act or refusal to act and has used the least restrictive means to further that interest.” Rev. Stat. 446.350. He has not, and he cannot meet his evidentiary burden in light of his orders—particularly his decision to permit the continued operation of “typical office environments, factories, or retail or grocery stores where large numbers of people are present, but maintain social distancing.”

Simply put, permitting worshippers to attend a service where everyone typically remains in the same spot throughout (all the while social distancing) will logically place fewer Kentuckians within six feet of one another than shopping at a grocery store, hardware store, or other retail business where they will continuously pass one another, stand in line together, or bump into one another as they turn a corner. And that is not to mention that in such retail establishments shoppers will pick up and put back goods, push the same shopping carts, and touch the same credit card machines….

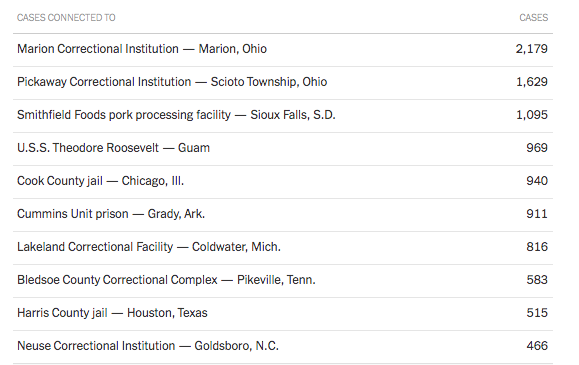

Other clusters include Lakeland Correctional Facility in Michigan, where more than 600 inmates have

Other clusters include Lakeland Correctional Facility in Michigan, where more than 600 inmates have