David Lat answers the questions we all want to know. At his excellent Substack site, David breaks down which Circuit Judges and Circuit Courts have fed the most Supreme Court clerks over the past five years. (If you haven’t subscribed, you should).

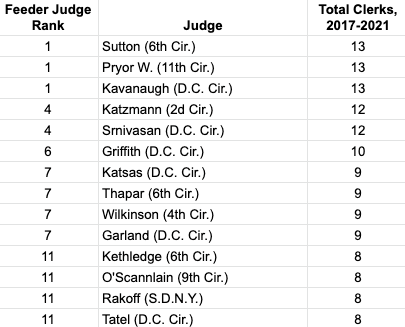

There is a five-way tie for first place between Judges Sutton, Pryor, and Kavanaugh. Each has 13. It is impressive that Kavanaugh is still feeding clerks, since he left the D.C. Circuit nearly three years ago. Sutton and Pryor are giants. Columbus and Birmingham are not exactly the most desirous places for law school grads to clerk–I very much like both cities–but these two jurists have built judicial fiefdoms in their backyards. Kudos to them.

There is a five-way tie for first place between Judges Sutton, Pryor, and Kavanaugh. Each has 13. It is impressive that Kavanaugh is still feeding clerks, since he left the D.C. Circuit nearly three years ago. Sutton and Pryor are giants. Columbus and Birmingham are not exactly the most desirous places for law school grads to clerk–I very much like both cities–but these two jurists have built judicial fiefdoms in their backyards. Kudos to them.

There is a two-way tie for second place between Judges Katzmann and Srinivasan. Each has 12. Judge Katzmann passed away, so his totals will likely decline in the future. At this point, Judge Srinivasan is the undisputed Democratic SCOTUS feeder. It’s not even close. Though with only three Democratic Justices, it will be hard to keep up these numbers. RBG’s four seats will now be filled by ACB.

Judge Griffith is in sixth place with 10. He retired from the D.C. Circuit, so his totals should drop in time.

There is a four-way tie for seventh place between Katsas, Thapar, Wilkinson, and Garland. Each has 9. Katsas’s numbers are really impressive, as he was only appointed to the Court in December 2017. If we assume Katsas has four clerks per year, he has had (roughly) 16 law clerks. More than half of them clerked on the Supreme Court. Wow! Judge Thapar’s rank is also impressive. He was only elevated to the Circuit Court in 2017, but many of his district court clerks went onto higher office. Judge Wilkinson has been a judge for nearly 40 years. The fact that he only has nine SCOTUS in the last five years suggests his impact is slipping. Then there is former-Judge Garland, who I’ve called the Susan Lucci of the Supreme Court. (The closest he’ll get to One First Street will be when he argues a softball case as AG). Garland only had 9 clerks. But then again, he gets to install his favorite clerks in top executive branch positions. Just this week, Biden nominated Garland clerks as SG (Elizabeth Prelogar) and U.S. Attorney for SDNY (Damien Williams).

Finally, there is a four-way tie for eleventh place. Judges Kethledge, O’Scannlain, Rakoff, and Tatel. Each has 8. Judge Tatel has taken senior status, but his influence should remain constant if he keeps a full complement of clerks. (We still do not have a nominee for his seat). District Judge Rakoff often fed clerks to Katzmann. That pipeline is now gone. Judge O’Scannlain has been on senior status for nearly five years, but he is still feeding his fair share to the Court. Judge Kethledge, the other Kennedy clerk who could have filled the vacancy, rounds out the Sixth Circuit’s dominance.

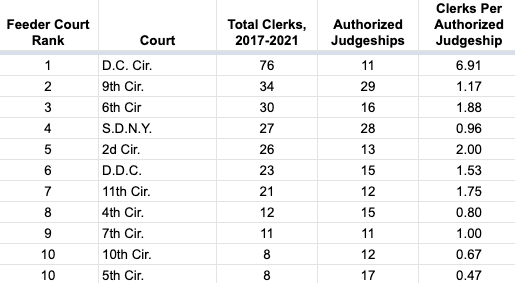

David Lat also calculated how many SCOTUS clerks each circuit fed to the Supreme Court. I think the most useful measure is “clerks per authorized judgeship.”

The D.C. Circuit is far and ahead in the lead with almost 7 clerks per each authorized judgeship. Kavanaugh, Srinivasan, Griffith, Garland, Katsas, and Tatel were all-stars. But three of those judges are now off the Court. Given the hard-left turn, it is unclear if the D.C. Circuit can maintain its supremacy. I don’t know how many Millett and Pillard clerks will get hired by the new Roberts Court. Judges Rao and Walker can make up some of that deficit.

The Second Circuit is in second place with 2 clerks per authorized judgeship. Alas, with Judge Katzmann off the Court, is unclear who else can rise to that occasion. Perhaps Judges Park and Menashi.

The Sixth Circuit is in third place with 1.88 clerks per judge. Very soon, the Sixth Circuit should overtake the Second Circuit. And in 5 years or so, it may give the depleted D.C. Circuit a run for supremacy. Judges Sutton, Thapar, and Kethledge are in their prime.

The Eleventh Circuit is in fourth place with 1.75 clerks per judge. Judge Pryor is leading the pack by himself, though Judges Grant and Newsom may start to climb the ranks.

After fourth place, the numbers drop off steeply. My, how the Ninth Circuit has fallen. Reinhardt is gone. Kozinski is gone. And the Obama nominees will have little cache with the conservative court. The Tenth Circuit only made the list because of then-Judge Gorsuch. It should drop off soon. My home circuit, the Fifth, is really slacking. Thankfully, some of the new Trump appointees will move up the line: Ho, Willett, Oldham, Duncan, and others.

There are three circuits missing from this list altogether: the First, Third, and Eight Circuits. I can’t think of any recent appointees to those courts that could alter the balance. It’s sad that SDNY and DDC produced more SCOTUS clerks than three courts of appeals. But there it is, we have a huge imbalance.

Thanks for David for running the numbers.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3m6rXYu

via IFTTT

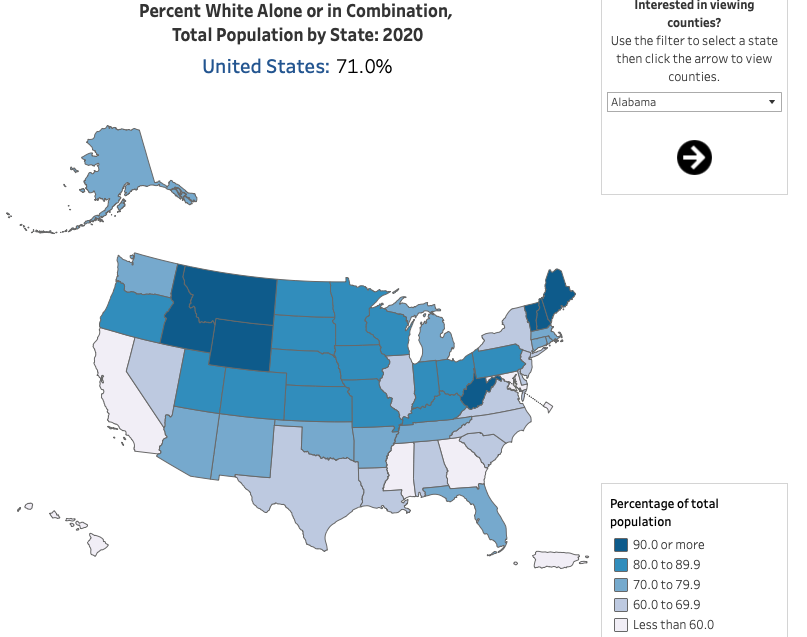

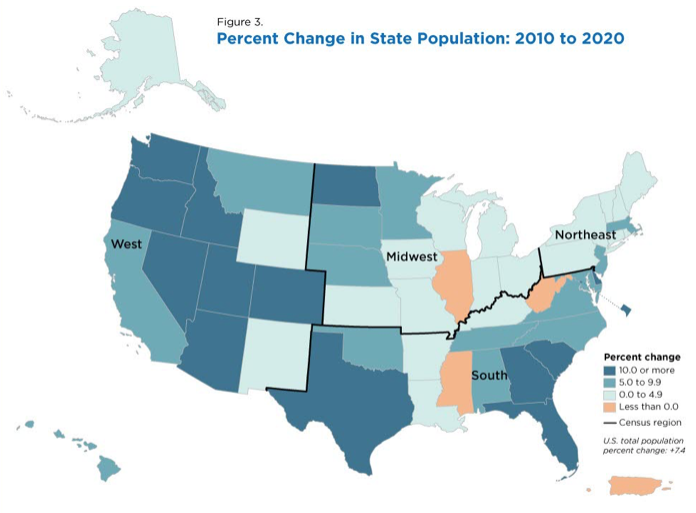

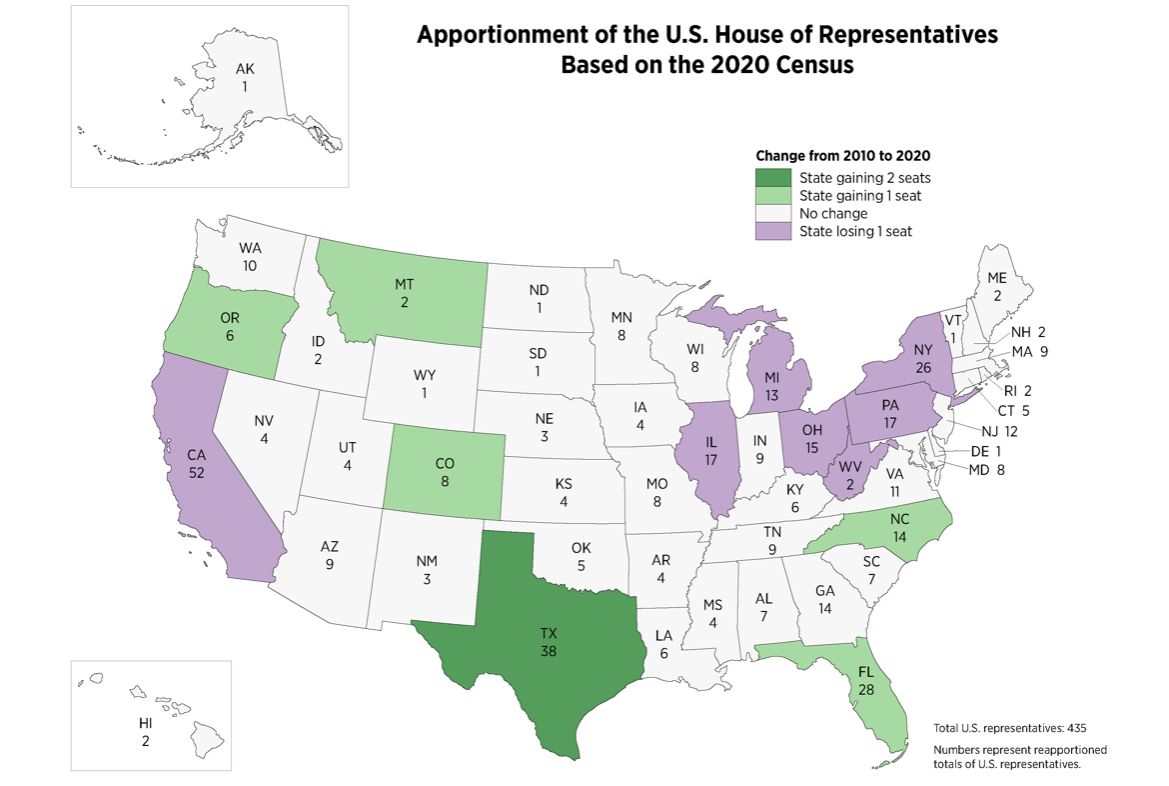

As result of these population shifts, New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, and California will each lose one representative. The congressional delegations from Oregon, Montana, Colorado, Florida and North Carolina will each grow by one, and Texas will gain two.

As result of these population shifts, New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, and California will each lose one representative. The congressional delegations from Oregon, Montana, Colorado, Florida and North Carolina will each grow by one, and Texas will gain two.