Authored by Kit Knightly via Off-Guardian.org,

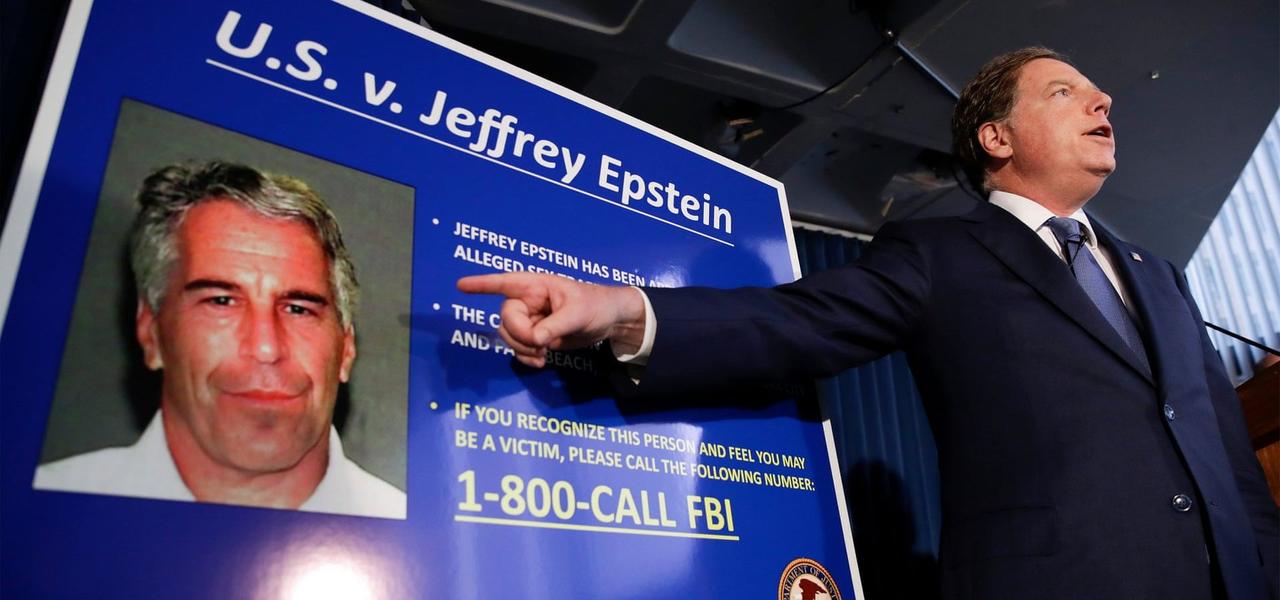

In two different opinion pieces The Guardian has made its position on the alleged death of Jeffrey Epstein clear – he “probably” committed suicide.

The first, titled Epstein conspiracy theories are farfetched – but can you blame people?, takes the position that although “conspiracy theories” about Epstein’s apparent suicide are “understandable”, there’s no evidence to support them.

Rather, the author endorses the slowly coalescing official narrative. Namely that of complete, systemic incompetence:

The official explanation for Epstein’s death comes down to rank incompetence. And it’s probably true.

A short-sighted attitude to take, which totally ignores a cardinal rule when dealing with state agencies: They will only admit to incompetence if the truth is worse.

The author also attempts to undermine the “conspiracy theories” by pointing out that Epstein was a potential threat to important figures on both sides of the political divide:

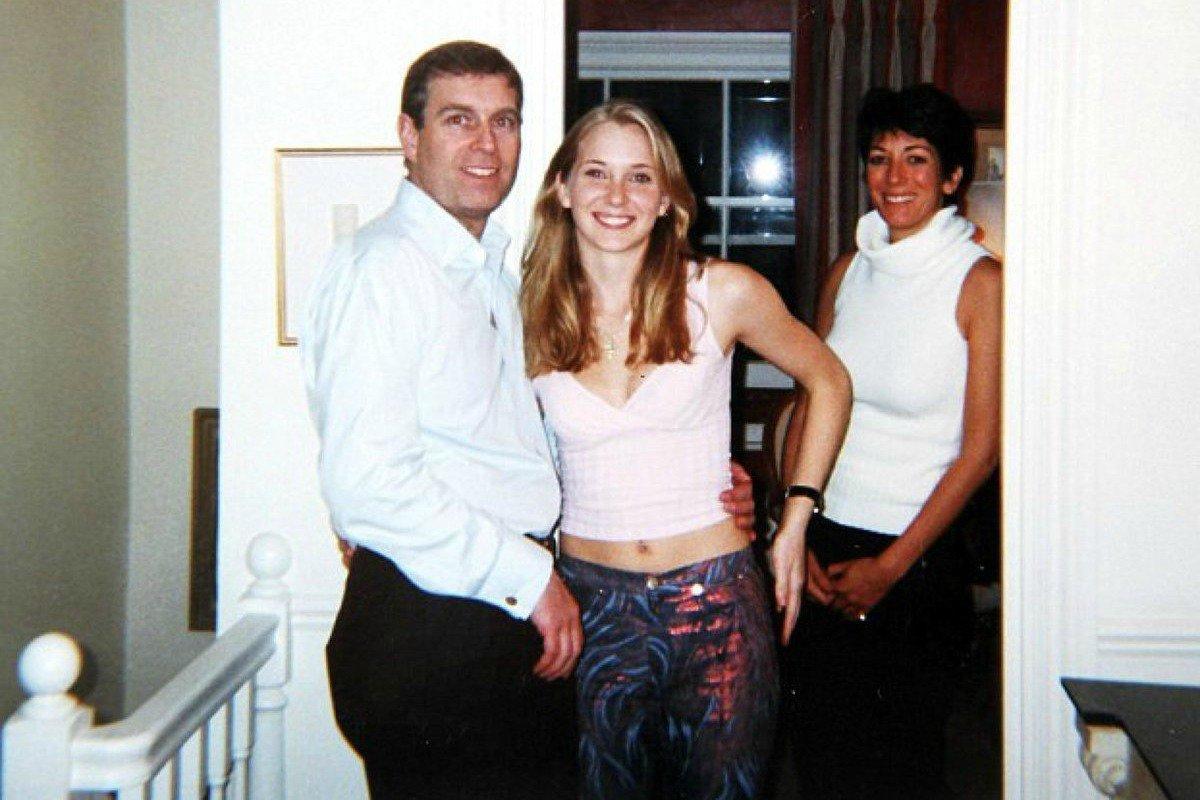

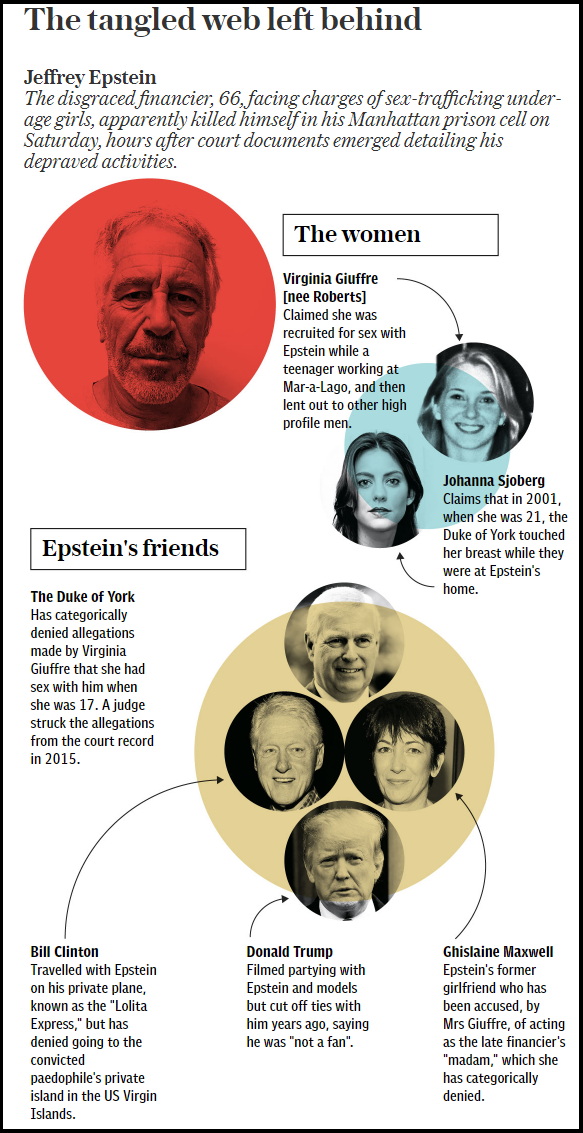

Online, conspiracy theories now abound. Observers suggest Epstein was killed by one of the men who may have been implicated in his crimes – maybe Bill Clinton, according to the fringe right, or maybe Donald Trump, according to the fringe left.

An argument rather akin to saying “he can’t possibly have been murdered, because there were too many people who wanted him dead. There are SO MANY plausible suspects, that the only reasonable explanation is that…none of them did it.”

(Also, note the word “fringe”, a manipulative use of language designed to discredit an idea without engaging with it rationally)

However, this article – although laced through with traditional mainstream rhetoric about “conspiracy theories” – at least leaves them room to exist.

The Guardian’s other Epstein piece is rather less understanding: Epstein’s death is a victory for misogyny: it denies accusers the justice they deserve

Blares the headline (further evidence that very few people at the Guardian seem to know what “misogyny” really means), before continuing by taking aim at conspiracy theories several times in the text.

Firstly, in an almost word-for-word quote from the previous column:

Commentators on the right speculated that he had been murdered by powerful liberals; those on the left speculated that he had been murdered by powerful conservatives. These theories were not responses to evidence, of which there is little

And then later claiming conspiracy theories not only “factually wrong” (something no one can know at this stage)…

The speculations may well be factually wrong – criminal justice experts have pointed out that inmate suicides are common, and that those detained in federal jails often face startling neglect

…but also attempting to Mrs Lovejoy the public by claiming “conspiracy theories” are actually harmful:

the positing of these conspiracy theories is unhelpful, distracting from the important injustice that has been done to Epstein’s victims.

Declaring seeking the truth to be somehow unfair to the victims is a classic trope, deployed most famously against 9/11 Truthers, but common after many such incidents.

There’s also this sentence…

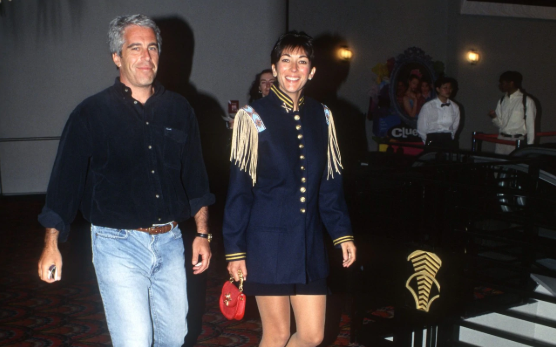

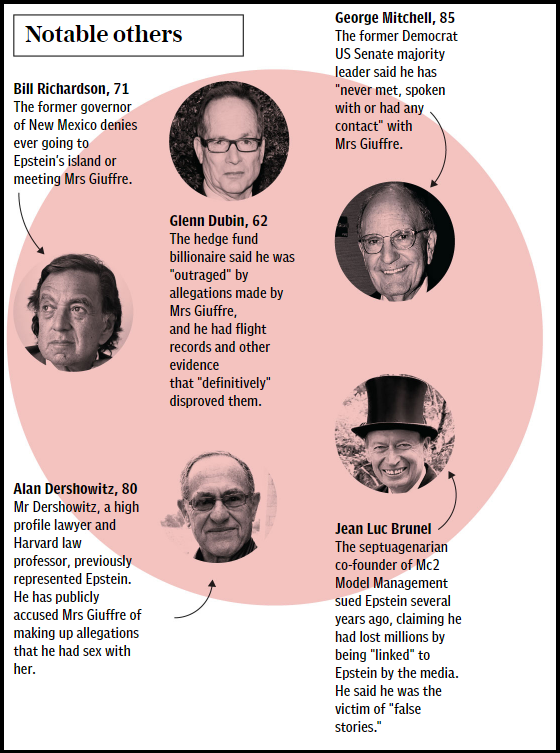

The conspiracy theorists also risk undermining efforts to bring Epstein’s co-conspirators to account: their suggestions that the financier was killed to cover up the rapes and assaults of powerful men who would rather he be shut up could lend suspicion to anyone pointing out the breadth of his alleged pedophilia ring, giving those who want continued investigations of men such as Dershowitz, Pritzker and Dubin the aura of a maniac in a tinfoil hat.

Which, I’ll be honest, I simply don’t understand.

I think she’s arguing that “conspiracy theorists” talking about “conspiracy theories” might discredit the very real possibility there was an actual conspiracy.

If that’s what she means – because I honestly do not understand the words – well, that’s obviously just crazy. You can’t argue we shouldn’t talk about conspiracy theories, just in case there’s a conspiracy fact.

That’s the attitude of a person so brainwashed by the idea that “conspiracy theorist = crazy person” that they can no longer think in a straight line. Total cognitive dissonance.

The articles are different in tone, but they are united in purpose, and they each hit the same three key points:

-

Epstein “probably” killed himself. After all, inmates commit suicide all the time.

-

Conspiracy theories might look reasonable, but they are factually incorrect and morally harmful.

-

The real tragedy here is the poor victims who will go unavenged. We should all focus on that, not investigating the potential murder.

All this serves to demonstrate – for about the millionth time – the entire purpose of outrage culture and identity politics. Fear of being offensive used to control a conversation and dictate narrative: Don’t talk about Epstein being murdered, don’t even think about it. If you do, you’re a misogynist.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/31IOoFX Tyler Durden