In California, wildfires have burned more than 3.2 million acres—an area larger than the state of Connecticut—since January. Since August 15, the state’s fires have killed at least 24 people and destroyed more than 4,200 structures. The amount of the state’s forestland that has burned this year is has been described as “unprecedented” and “record-breaking.”

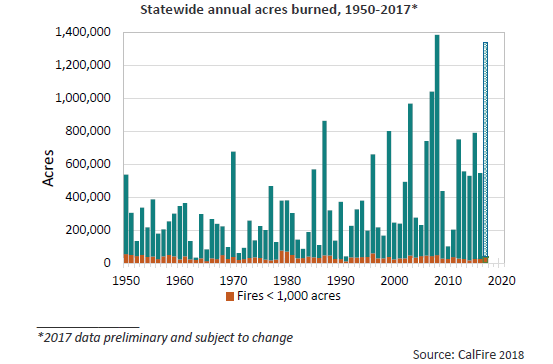

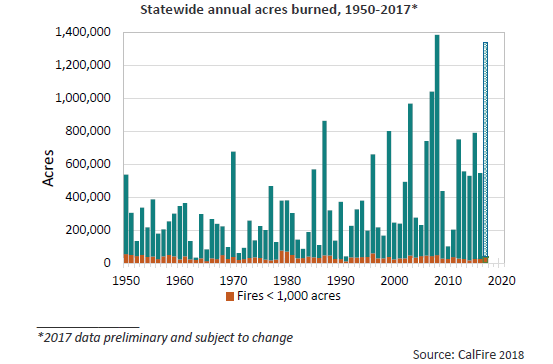

The area annually burned by wildfires has been zig-zagging upward since 1950. The chart below displays data through 2017; subsequently, Cal Fire reports, the wildfires consumed 1.6 million acres in 2018 and 260,000 in 2019 respectively.

The latest area burned may not be as unprecedented on a longer time scale. For example, a 2007 study in Forest Ecology and Management suggests that the area in California burned by Native Americans to manage landscapes, as well as those sparked by lightning before the era of European settlement and active fire suppression, may have fallen between 4.5 and 12 million acres annually. “The idea that US wildfire area of approximately two million hectares (about 5 million acres) annually is extreme is certainly a 20th or 21st century perspective,” wrote the researchers. “Skies were likely smoky much of the summer and fall in California during the prehistoric period.”

In the 20th century, the National Interagency Fire Center reports that the area annually burned by wild land fires in U.S. (not just California) may have exceeded 50 million acres in 1930 and 1931. But the agency cautions that the less rigorous methods for collecting and compiling these early 20th century data means that “figures prior to 1983 should not be compared to later data.” For example, the data from the 1930s may well include fires intentionally set in the Southeast to clear agricultural land.

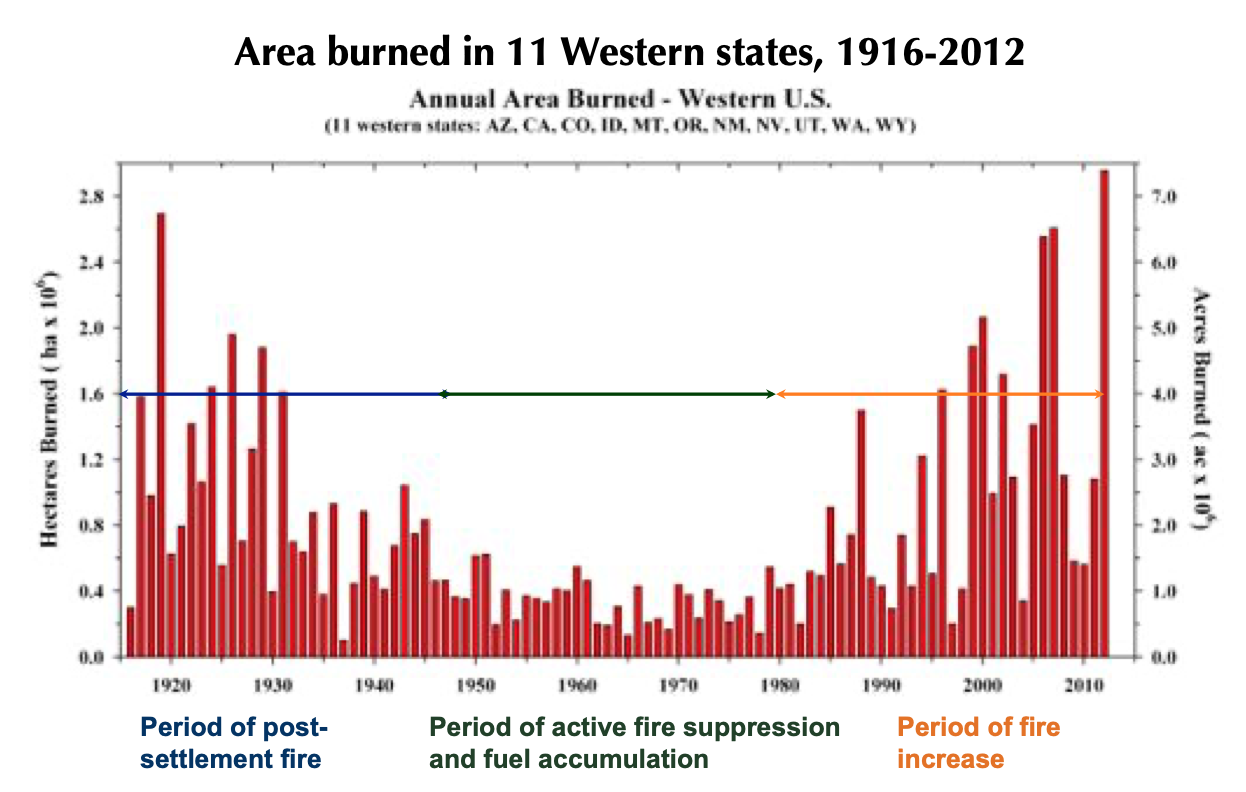

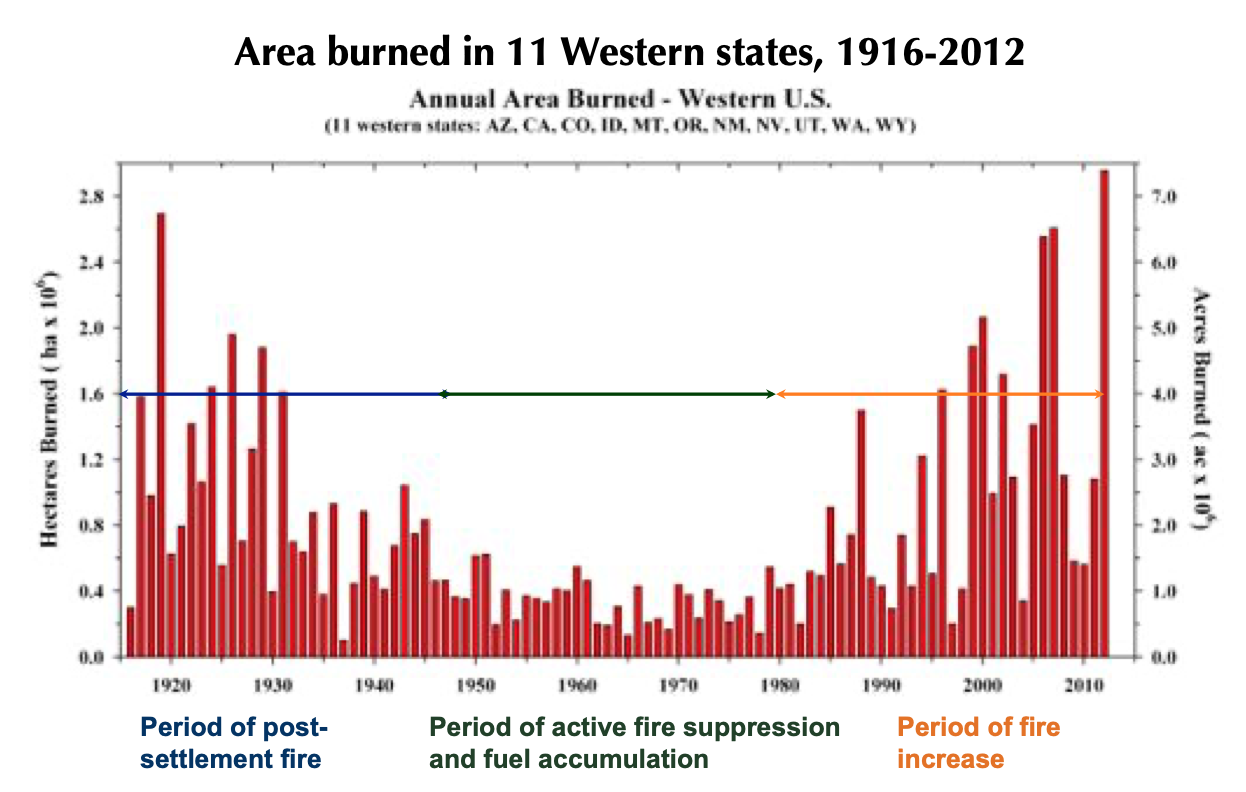

A 2009 study in Ecological Applications (data updated here) identified a U-shaped trend in 11 western U.S. states, in which fires burned more space at the beginning of the last century, less in the middle decades, and more again recently:

What is causing the upward trend in the area burned by wildfires in the western U.S.? During a visit to California this week, President Donald Trump suggested that bad forest management is the chief cause. During the briefing, California Gov. Gavin Newsom gingerly suggested that “the science is in and observed evidence is self-evident that climate change is real, and that is exacerbating this.” In fact, both have played a role, as has the complicating circumstance that millions of Californians have moved to fire-prone wildlands.

A 2009 report from researchers associated with California Polytechnic State University observed that bad forest management, including active fire suppression and restrictions on timber harvests, have “resulted in an unnatural accumulation of fuels on many California forestlands.” The report further noted: “Where 50–70 trees per acre stood before the Gold Rush, California forests now average over 400 trees per acre. When fire enters these ecosystems the resulting high-intensity wildfires are as unnatural as the accumulated fuels that they consume.”

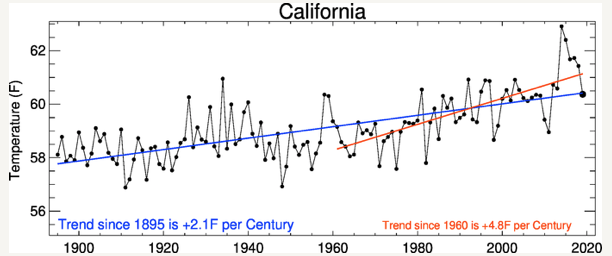

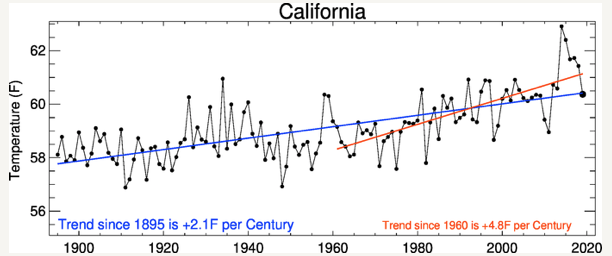

Meanwhile, California’s climate has been heating up and periods of drought have been deepening and lengthening. Using surface temperature data, a team led by University of Maryland atmospheric chemist Clark Weaver calculates that California, since 1895, has been growing warmer at a rate of about 2.1° Fahrenheit per century. The warming sped up over that time: From 1960 to today, the rate is 4.8° per century.

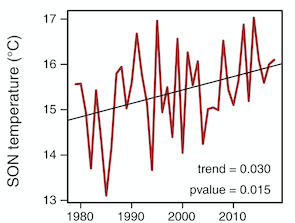

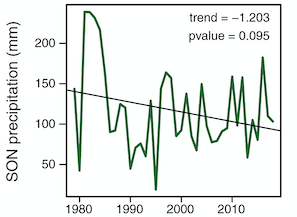

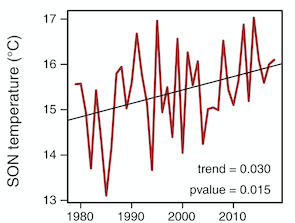

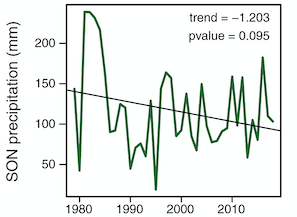

An August 2020 study in Environmental Research Letters finds that since 1979, a combination of rising temperatures and falling average precipitation has increased the likelihood of extreme autumn wildfire conditions across California. The researchers report trends for the months of September, October, and November (SON) in both temperatures (up about 1° Celsius) and precipitation (down an average of 30 percent), making fire weather conditions about twice as worse statewide.

The researchers find that from 1984 to 2018, the trends toward a hotter and drier California temperature correlate with a increase of about 40 percent per decade in the size of the statewide autumn-burned area.

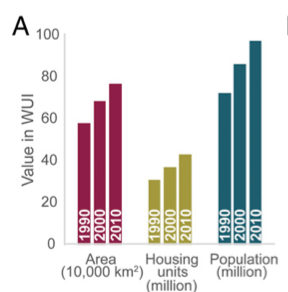

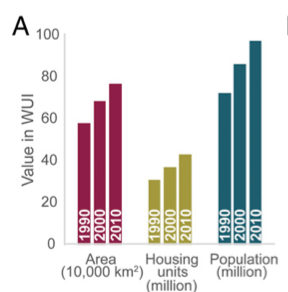

As all this was happening, more people were heading into the woods, that is, making their homes in the “wildland-urban interface” (WUI) areas where houses and wildland vegetation meet and intermingle. Some go there because they can’t afford to live in pricey urban areas with strict restrictions on new building, while other, more fortunate people move to the woods to enjoy the scenery, wildlife, and outdoor activities.

A 2007 report in the International Journal of Wildland Fire found by 2000, some 3.5 million California housing units were located in WUI areas, with another 1.5 million intermixed within and surrounded by wild landscapes. On top of that, 62 percent of net California housing growth from 1990 to 2000 occurred in WUI zones. A 2018 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reported that America’s wildland-urban interface “grew rapidly from 1990 to 2010 in terms of both number of new houses (from 30.8 to 43.4 million; 41% growth) and land area (from 581,000 to 770,000 km2; 33% growth), making it the fastest-growing land use type in the conterminous United States.”

In other words, more and more Americans have moved into areas where the wildfire risk is higher:

The measure that could make a big difference with respect to California wildfire risk is, as the president advised, better and more proactive forest management. As it happens, the federal government, which the president oversees, owns 57 percent of California’s forests, whereas state and local governments own around 3 percent. (The rest is in private hands.)

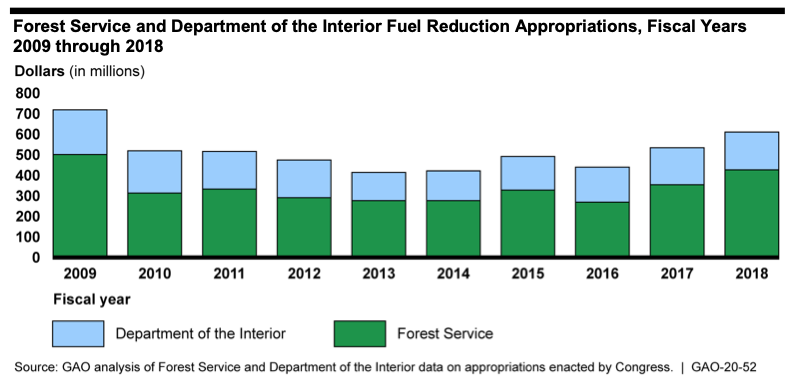

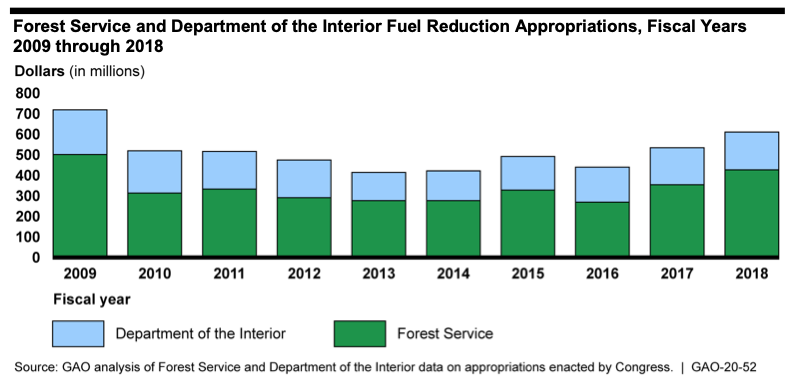

Better forest management to reduce wildfire risk chiefly involves reducing the fuel load in overgrown fire-suppressed forests using mechanical harvesting and prescribed burns. A 2019 Government Accountability Office report found that federal agencies spent around $5 billion on reducing wildland fuels from 2009 to 2018:

The Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management estimate that more than 100 million acres of federal lands are at high risk from wildfire, but in 2018 the agencies managed to treat only about 3 million acres.

The Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management estimate that more than 100 million acres of federal lands are at high risk from wildfire, but in 2018 the agencies managed to treat only about 3 million acres.

An intriguing 2019 study in Fire notes that 70 percent of all prescribed fire between 1998 and 2018 was completed by non-federal entities in the Southeastern U.S. In other words, private owners and state agencies in the Southeast have completed more than twice as much prescribed fire as the entire remainder of the country. “This may be one of many reasons why the Southeastern states have experienced far fewer wildfire disasters relative to the Western U.S. in recent years,” the researcher observes. It is worth noting that the federal government owns just a small percentage of the land in most Southeastern states.

A 2020 study in Nature Sustainability estimated that 20 million acres of California forestland—about 20 percent of the state’s land area—would benefit from prescribed burning to cut the risks of catastrophic wildfires. Yet California intentionally burned just 50,000 acres in 2017. The costs for prescribed burns range from $100 to $500 per acre. That suggests that it would take roughly $2 billion to $10 billion to treat 20 million acres. For comparison: In its latest budget request, the U.S. Forest Service says it has a backlog of 80 million acres in need of active management but plans to reduce fuel loads on just over 1 million acres in 2021. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees the Forest Service, suggested in a July 2020 report that “restoration of national forests comes with an estimated price tag of $65 billion.”

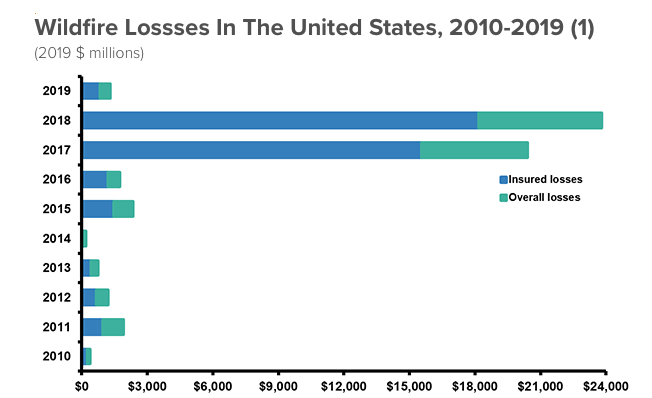

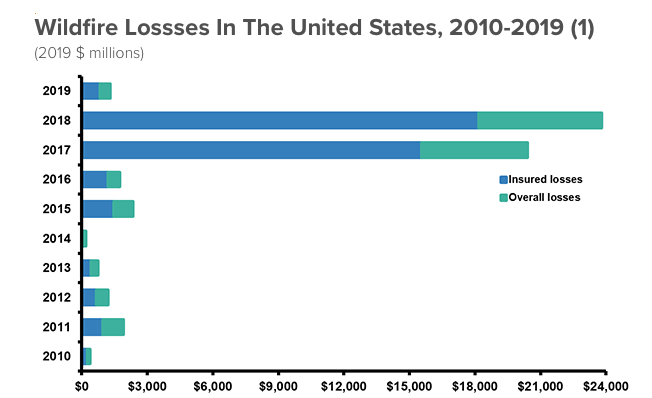

The insurance risk analytics firm Verisk assesses the primary factors that contribute to wildfire risk—fuel, slope, and road access—to determine a property’s individual wildfire hazard score. The company finds that more than 2 million properties in California are at high and extreme risk from wildfire. (Nationwide, about 4.5 million properties are at high wildfire risk.) The Insurance Information Institute reports that annual insured wildfire losses in the U.S. generally hovered below $1 billion from 2004 until 2017. In 2017 and 2018, insured wildfire losses escalated to around $15 and $17 billion, respectively, before dropping back down in 2019 to around $1 billion. U.S. insured wildfire losses so far this year are estimated at around $3 billion:

After the spectacular wildfire losses in 2017 and 2018, insurance companies have revised their risk models and are now pulling out the California market. Why? Because the premiums that state regulators allow insurers to charge don’t cover their projected wildfire risks. By one calculation, insurers covering California wildfire losses paid out more than $2 for every $1 in premiums in 2017 and $1.70 for every $1 in premiums in 2018. With that dynamic, it is not surprising that insurance companies have dropped wildfire coverage for nearly 350,000 California homeowners since 2015. Property owners who can still buy insurance in the market have seen their premiums increase recently by as much 300 to 500 percent.

In the wake of 2018’s disastrous fires, the California legislature passed Senate Bill 824, which prohibits cancellation or nonrenewal of homeowners policies within a year of a declared state of emergency if a structure is either in an area where a wildfire occurred or adjacent to a fire perimeter. In December 2019, California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara imposed a mandatory one-year moratorium on insurance companies refusing to renew certain policies; this applies to least 800,000 homes in California wildfire disaster areas.

As more Californians lose their standard wildfire insurance coverage, they have been turning to the state’s Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) plan to protect their properties. The FAIR plan is basically a high-risk insurance pool that offers last-resort, bare-bones coverage, chiefly for fire losses, to property owners who cannot obtain a policy in the regular market. It was established in 1968, in the wake of urban riots and brush fires, when the California legislature required insurance companies offering property policies in the state to create and contribute to the plan. It is not taxpayer-financed, and plan premiums are statutorily required to be actuarially sound.

The FAIR plan’s premiums have been increasing at a rate of 8 percent per year since 2016. This year, the program got regulators’ permission to raise its rates by 15.6 percent—after trying to hike them by 35 percent.

Being unable to obtain insurance means, of course, that owners will find it much harder to sell, since banks will not issue mortgages for uninsurable properties.

Recognizing that his one-year nonrenewable mandate forcing insurance companies to maintain fire policies is coming to its end, Insurance Commissioner Lara announced this week that he is convening an investigatory hearing in October that will focus on ways to protect California residents against increasing wildfire risks. “Our current reality of increasing insurance premiums and non-renewals hurts those who can least afford it, including working families and retirees on fixed incomes,” said commissioner Lara in a press release. “We can lower the insurance risk by incentivizing people to bring down the fire risk on their properties and in their communities with clear, science-based home-hardening standards.”

Home-hardening could help, but not perhaps as much as the commissioner and property owners may think. A 2019 Fire article analyzed the factors associated with structure loss in the California areas burned by wildfire from 2013 to 2018. Analyzing how more than 40,000 structures exposed to wildfire fared, the researchers found that “in most regions home structural characteristics are far more important in determining home survival than defensible space.” (Defensible space generally means cutting back brush and trees as much as 100 feet to establish a perimeter around a house.) They added that many “destroyed structures could be characterized as ‘fire-safe,’ such as having >30 meters of defensible space or fire-resistant building materials.”

So why would one of the most frequently referenced protection measures—expanding defensible space—have so little impact on whether a house survives a wildfire? Because flying embers that precede the fire front by a mile or two often waft over the cleared perimeter to set houses alight. Measures that do somewhat increase the chances that a house will survive a wildfire are having enclosed (or no) eaves, multiple-pane windows, and screened vents. These tend to exclude embers from gaining entry into more combustible parts of a structure.

If this study is right, the home-hardening measures that commissioner Lara wants insurance companies to take into account when setting premiums will probably not have much impact on whether Californians who live in fire-prone areas can obtain coverage or reduce what those who can get coverage pay for their policies.

Whatever is sparking the upsurge in wildfires, California regulators and residents should take market signals seriously when deciding where to live. As the Pomona College environmental historian Char Miller recently put it in The New York Times, insurance companies ask themselves: “Why am I insuring something that I know is going to be destroyed?” Homeowners should certainly be asking themselves a similar question.

Meanwhile, a 2007 analysis in the Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics found that repeated fires in any given area of Southern California brought down property values. “The first fire reduces house prices by about 10 percent,” they calculated, “while the second fire reduces house prices by nearly 23 percent.” Both insurance rates and resell prices are signals that living in the woods is costly. Many people may be willing to take the risk of losing their property to wildfire, but insurance policyholders or taxpayers should not be forced to subsidize that choice. Charging people the full cost of their fire risks could well incline them to build and live in safer areas.

A fascinating 2016 Stanford Law Review article highlights that point. The authors, legal scholars Omri Ben-Shahar and Kyle Logue, observe that insurance can serve “as a form of private regulation of safety—a contractual device controlling and incentivizing behavior prior to the occurrence of losses.” Their focus is on flood insurance, but the point is valid for fire coverage too:

In the U.S., insurance is denied its potential role as an efficient regulator of pre-storm conduct. It does not induce rational precautions by individuals, cost-justified community development by localities, or efficient infrastructure investment. American insurance fails to achieve these straightforward and enormously important roles for a reason that can be stated in one sentence: insurance policies for weather related losses are not priced to reflect the real risk. As a result of government intervention in property insurance markets, through either rate regulation or direct government provision of subsidized insurance, private markets no longer generate prices signals regarding the cost of living in severe weather regions. The cost of insurance is suppressed, thus failing to alert private parties who purchase property insurance to the true risk of living dangerously. It allows these private parties to (rationally) assume excessive risk, and dump the cost of living in the path of storms on others. Indeed, much of the development of storm-stricken coastal areas is due to insurance subsidies, and would likely not have happened at the same magnitude otherwise.

Insurance could contribute at least modestly toward mitigating California’s rising wildfire risks. Although it is way too bureaucratically complex and slow, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has a severe repetitive loss program hints at a way forward. That voluntary program buys out homeowners whose property has been flooded numerous times and encourages them to relocate to higher ground. FEMA has acquired more than 43,000 such flood-prone properties since 1989. A streamlined buyout program for structures destroyed by wildfire, ideally run by private insurers, could give residents of high-risk areas a stronger incentive to relocate and rebuild elsewhere.

One preliminary idea, based on what has been happening with many FEMA buyouts, is that insurers might pay the pre-fire value for burnt-out properties and communities, then turn the now-vacant land over to local land trusts to oversee and manage.

Another innovative measure that would help homeowners reduce their wildfire risks is to issue forest resilience bonds (FRBs). These raise private capital to fund forest restoration efforts, such as mechanical harvesting and prescribed burning, that reduce the chances of wildfire. Smaller fires mean lower costs. The bond issuers—who could be government entities, but could also be utility companies or other private parties—reimburse the investors over time. For example, a $4.6 million FRB was issued in 2018 to treat and lower the fire risks on 15,000 acres of forestland in the North Yuba River watershed via tree thinning and prescribed burning. Instead of waiting for action and fickle funding from distant federal and state agencies, local communities at high risk of wildfire could issue such bonds and begin forest restoration sooner. Insurance companies might even invest in such bonds, and could also factor the lower fire risk into their premiums for that community’s homeowners.

An alternative to state and federal wildfire suppression is privately provided wildfire fighting. The Montana-based Wildfire Defense Systems (WDS) has been offering just such services since 2013. Insurance companies contract with WDS to evaluate the wildfire risks of policyholders and advise them on how to lower those risks. WDS also offers insurers access to private firefighting services that are on-call across 20 states.

The Trump administration is right to complain about poor forest management, but it has been offering no credible plans for fixing it. And California’s insurance regulators seem dead set on policies that will eventually drive private insurance companies out of the state. Meanwhile, forests burn, thousands flee their homes, and millions choke on smoke.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3ccr0XK

via IFTTT

The Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management estimate that more than 100 million acres of federal lands are at high risk from wildfire, but in 2018 the agencies managed to treat only about 3 million acres.

The Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management estimate that more than 100 million acres of federal lands are at high risk from wildfire, but in 2018 the agencies managed to treat only about 3 million acres.