By the third week of March 2020, visiting the local grocery store had become a precarious undertaking. Part of it was the sheer strangeness of distanced shopping. I had become acutely aware of my physical distance from other people. Soon I noticed them eyeing me from behind their carts with a similar wariness.

In the produce section, I hovered a body length or two behind fellow shoppers, waiting for them to bag their bundles of bok choy, unsure how much buffer was considered polite. Nobody wanted to risk the skirmishes over the last rolls of toilet paper we’d seen in videos circulating online; purchasing small cabbages should never be an event that goes viral.

Things grew even stranger in the meat section, where paper signs affixed to refrigerated cases told customers they could have only a few pounds of ground beef and pork at a time. Likewise at the milk case. When I finally got to the canned beans section, it was picked clean; my neighbors had apparently decided legumes would get them through the biggest, weirdest public health crisis any of us had ever seen.

Across the country, the story was the same: Once-common food items became difficult to obtain. Grocery delivery services were suddenly impossible to book and rarely yielded a full order when they did arrive. Grocery stores shelves weren’t completely bare. But they were short on many items I’d come to expect would always be available.

The quantity limits and distancing rules were an inconvenience for office workers confined to work from home. For those already struggling with poverty and those who had abruptly found themselves unemployed, the situation was more dire.

For the first time in nearly a century, Americans across the income spectrum were dealing with widespread food shortages and uncertainty brought on by a crisis. Widespread fears and state-enforced lockdowns combined to shutter production facilities and break supply chains to an extent few had ever contemplated.

In response to those closures and the novel challenges they created, Americans changed the food they bought and the meals they ate in ways that are likely to echo for generations to come. As the virus spread and tens of millions of people were forced to stay inside, many of them turned to home cooking projects that would have been unimaginable—or at least unnecessary—just a few months earlier.

Yet as unusual as all this was, it also wasn’t entirely new. Just as pandemic lockdowns and COVID-driven shortages reshaped food culture in 2020, government rationing and food restrictions during World War I and World War II changed how Americans shopped, cooked, ate, and thought about their meals for a century after. For better or worse, the same is happening today.

Voluntary Rationing

When America entered World War I in April 1917, its food supply was thrown into disarray. At the time, nearly a third of Americans lived on farms. All at once, large numbers of able-bodied agricultural workers entered military service.

Transportation disruptions also made supply chains less stable than before. The government suddenly had to build capacity to deliver food to soldiers stationed in combat zones abroad. President Woodrow Wilson created the U.S. Food Administration, which deployed slogans such as “food will win the war” to convince American families—primarily women, who shouldered the majority of the cooking burden—of the necessity, and even virtue, of restraint.

The government limited the amount of sugar that could be bought by wholesale producers and industrial manufacturers, but it chose not to ration sugar or other foods for American households. Instead it relied on propaganda campaigns appealing to patriotism to spur voluntary efforts. As Amy Bentley, a professor of food studies at New York University, details in Eating for Victory: Food Rationing and the Politics of Domesticity, the voluntary measures largely worked. From 1918 to 1919, American food consumption dropped by 15 percent.

But then as now, the impact was unequal. Voluntary measures were honored more by wealthy households than by the working class. When the government encouraged people to abstain from wheat and meat on certain days of the week, richer housewives largely complied. But some poorer households actually prospered in wartime and their consumption reflected that: “Immigrants and those in the working classes, whose war industry-related jobs produced higher incomes, increased their food intake,” writes Bentley. “Beef consumption, for instance, actually went up during the war.”

When World War II arrived, food supply issues became even more critical. As before, the government needed to supply high-energy foods to troops stationed abroad. At the same time, the lend-lease policy, enacted in 1941, committed Washington to providing food, oil, and weaponry assistance to Allied countries, which ended up accounting for 17 percent of U.S. war expenditures.

Some policy makers worried that advertisers—the powerful Madison Avenue ad men—would spur people back home to hoard food and other supplies by stoking fears of shortages. Others fretted that Americans would refuse to participate in voluntary consumption cutbacks because of a post-Depression psychological aversion to going without.

People “were understandably wary of a government requesting them to reduce their food intake, when during the depression people had watched it destroy millions of tons of food in the quest to stabilize agricultural prices,” Bentley notes—a reference to the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act. The New Deal legislation had authorized the federal government to buy and cull livestock and to pay farmers to limit the planting of basic crops.

To drive up food prices for the benefit of the agricultural sector, people across the country were allowed to starve. As John Steinbeck put it in The Grapes of Wrath, “The works of the roots of the vines, of the trees, must be destroyed to keep up the price, and this is the saddest, bitterest thing of all….The smell of rot fills the country.”

The feds concluded that in order to reduce food consumption on the scale needed to meet their wartime obligations, coercive measures would be necessary.

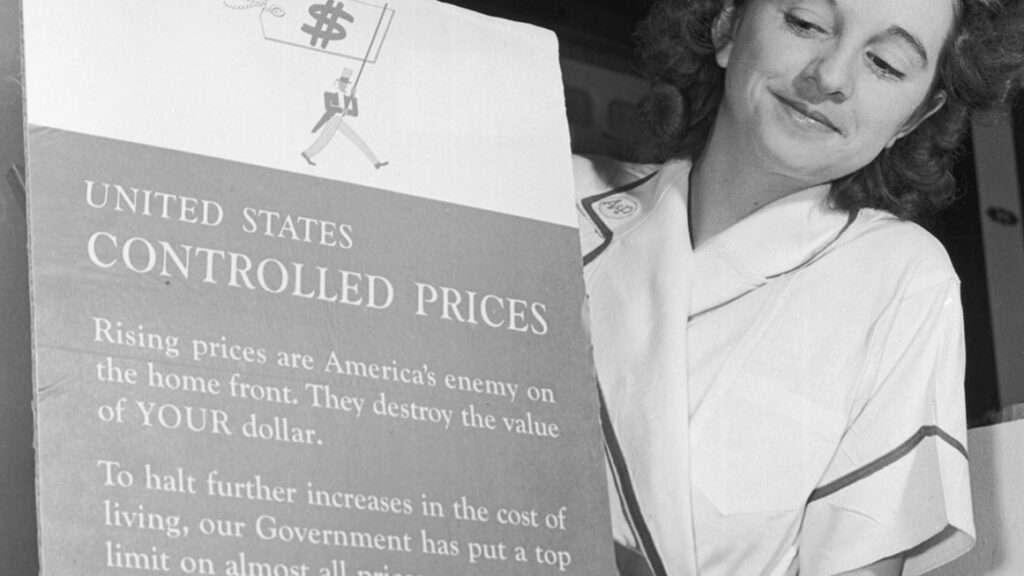

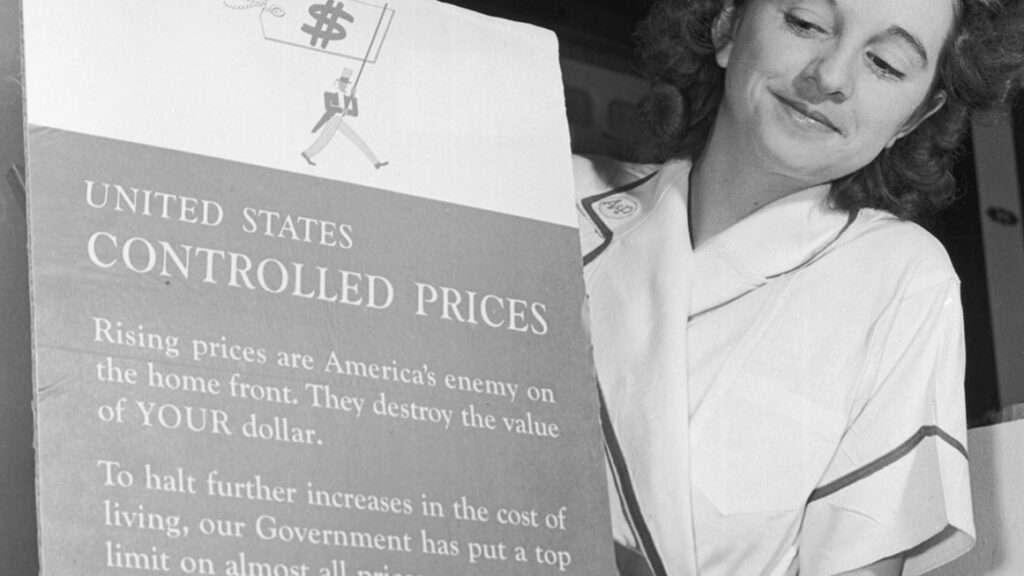

Price Controls and Ration Books

In January 1942, the Emergency Price Control Act let the Office of Price Administration (OPA) set price limits and impose mandatory rationing on a wide array of goods during wartime. The goal was to discourage the twin evils (in the government’s telling) of hoarding and gouging so that there would be enough for everyone. By spring, Americans could no longer buy sugar without a ration book. By November, coffee was added to the list. By March 1943, meat, cheese, oils, butter, and milk were all being rationed.

The buying and selling of gasoline, shoes, clothing, rubber tires, and medicines such as penicillin—which was distributed via triage boards in hospitals—were all controlled by the government. Propaganda attempted to convince Americans that fresh meat ought to go to men at war, not their own dining room tables. “American meat is a fighting food,” read the pamphlets. Fresh meats “play a part almost on par with tanks, planes, and bullets” in the war effort.

The system worked like this: People would line up at the local school to get their ration book, which included a certain allotment of stamps. Teachers were entrusted with the distribution.

In the beginning, stamps entitled the holder to a specific amount of a specific product, such as sugar or coffee. Each person was allotted one pound of coffee every five weeks, or roughly a cup a day.

Point-based rationing was introduced a bit later. The OPA would issue every American five blue stamps and six red ones per month, with each stamp worth roughly 10 points. The agency then allotted points to different food items, such that blue points could be used for canned or dried foods and red points could be used for meat, fish, and dairy.

Grocery shopping became a complicated math equation, one that required buyers to know how many people were in their household and how many red and blue points they had in total but also to track the changing stamp-prices of different goods based on how scarce they were. Points didn’t expire, so if you knew a birthday or anniversary was coming up, you could save your stamps and abstain from meat now to get a few juicy, celebratory cuts of steak later on.

Of course, this was all contingent on the customer having the money to pay for the goods, as well as on the vittles being in stock by the time she went to use her points. Despite the intent of the program, this was not always a given.

Federal Bureaucrats vs. Local Communities

The OPA, to its credit, was somewhat aware that it was ill-equipped to make these convoluted pricing decisions from Washington. Since distant federal bureaucrats would struggle to understand the needs of specific groups and communities, 5,600 local OPA boards were established and tasked with adjudicating disputes and responding to changing circumstances on the ground. Across the country, 63,000 paid employees and 275,000 volunteers mobilized to aid in the homefront food rationing effort.

The program didn’t cause mass starvation, but the OPA proved inept at changing point values quickly enough to respond to changing supply and demand. Logistical problems were manifold: People lost their ration books and had to incur long wait times to replace them, which meant temporarily going without certain foods. When people died, relatives were instructed to return the deceased’s ration books, which sometimes didn’t happen.

Meanwhile, rationing collided with preexisting trends. American food culture had shifted away from single-pot meals such as stews, which had come to be seen as lowbrow and favored by recent immigrants. Instead, middle-class families now preferred the “ordered meal,” which typically involved a meat or fish plus two separate sides. Switching to the ordered meal had come to be seen as a mark of assimilation and Americanness, and people resisted a return to the humble casseroles, stews, and soups that made sense in an era of increased scarcity.

Upon receiving word that rationing would be implemented, people rushed to hoard whichever food was the latest target. Government policy was that you had to declare how much of the goods you had on hand when you received your ration book—but you were required to return only half the equivalent stamp value of your existing stockpile. So people still had an incentive to buy large quantities of whichever items they believed would soon be limited.

The OPA was slow-moving and bureaucratic, and it found it nearly impossible to respond to the nation’s diverse food requirements and expectations. It set the price of chitterlings (also called chitlins) so high that many black Southerners couldn’t afford them, in part because the mostly white bureaucrats did not realize that pig intestines cook down a lot, and that one pound of chitlins won’t actually go very far once fried or boiled.

It struggled to understand the needs of Jews who kept kosher. It did not know that migrant farmers and herders needed more canned goods than other groups, since they can’t always access fresh fruits and vegetables. Miners and loggers complained that they needed more red meat to keep their strength up, while vegetarians asked whether they could get a higher dairy allotment in lieu of meat.

When Japanese Americans were rounded up and placed in internment camps in 1942, federal officials had to decide whether they should receive ration books. Many of them were U.S. citizens ostensibly entitled to the same benefits and protections as native-born white Americans. The government nevertheless chose to withhold ration books from the interned population, feeding them instead with Army surplus materials: hot dogs, ketchup, Spam. Many cherished Japanese-American food traditions were erased or permanently altered by the government’s decision to deny families the basic freedom to choose for themselves what to cook and how to order their home lives.

Forgeries and Black Markets

It did not take long for people to find ways to creatively maneuver around these constraints. Some who forged ration books or sold stamps on the black market were met with arrests and jail time, though the vast majority got away with it. (In 1944, the OPA enforcement division found more than 300,000 violators, but court proceedings were initiated for only about 30,000.) Public opinion polling from the time showed roughly a quarter of Americans thought some amount of occasional personal black market activity was OK.

To combat forging, the OPA instructed cashiers not to accept stamps that they didn’t tear out of the books themselves. Naturally, people would say that the stamps had fallen out. People also bartered with friends, exchanging some of their less desired food stamps for ones they actually wanted.

Black markets also popped up on the distributor side. Small slaughterhouse operations surreptitiously dealt with local merchants and managed to stay free of the OPA’s regulatory clutches. Other merchants would help their regulars get around the rules by selling higher-quality cuts as cheap meats, like ground hamburger, which required fewer points.

One way to deal with rationing was to dine out often. With worker shortages on the homefront, women entered the workforce in droves, earning good money—and sometimes overtime pay and other enticing benefits—in factories. This meant they had both more disposable income and less time for cooking than they had been used to. But rationing was incredibly difficult for restaurants—some took to closing on certain days of the week to stretch their supplies further—so they weren’t always a reliable reprieve.

Instead of being rationed, some foodstuffs, like seafood, were diverted to canning. The cans were then shipped overseas to feed hungry troops. “Just because it wasn’t rationed didn’t mean it was going to be available,” noted Kim Guise, the assistant director for curatorial services at the National World War II Museum, in a video lecture last year.

But in hard times, sneakiness sometimes won the day. As one man reminisced in a 1973 New York Times article, “pocketing a few lumps from [a] restaurant sugar bowl became a common practice.” Despite a durable propaganda campaign to up people’s compliance, many were still fine with shirking the rules in little ways here and there.

Polling suggests the public, fearing shortages and inadequate nutrition, was largely in favor of price controls and rationing. But those efforts largely failed due to bureaucratic sluggishness. The OPA’s solution—hire thousands of local workers to enact a slew of complex rules—was incredibly expensive while still resulting in obvious failures to meet people’s needs. It’s almost impossible to fully quantify the effects of the OPA’s clumsy rationing schemes, but it’s clear that the federal government wasn’t up to the task.

Lockdown Living

Which brings us to today.

In March and early April 2020, governors in 42 states implemented full stay-at-home orders in an effort to stop the spread of the coronavirus. Three more states handed down partial orders. Bars and restaurants across the country were forced to close—and even in places where they remained open, many Americans, fearing a novel pathogen, chose to stay home rather than eat out.

Those temporary closures have led to more permanent ones: The National Restaurant Association estimates that the industry lost $240 billion and nearly 2.5 million jobs last year. More than 110,000 restaurants nationwide have closed, about one in six U.S. dining establishments. Just half of former restaurateurs say they will remain in the industry.

People began to fear that food supply disruptions would create dual crises: We would have to contend with a pandemic as well as shortages of groceries and other essential goods, all of which would upend the pattern of everyday life.

The immediate consequences were plain for almost anyone to see. Some quelled their worries with sourdough and banana bread. Baking from scratch became a pandemic rite of passage, at least for those comfortable remote workers who found it easiest to sequester themselves inside. Others planted victory gardens in an attempt to grow their own food, pass the time, and limit trips to the grocery store. For about three weeks, it seemed like every remote-working millennial was snipping scallions and stowing them in a glass jar to regrow them from their roots.

With restaurants closed and income streams suddenly tenuous, meanwhile, the nation’s chefs and food writers took to Instagram and YouTube to teach Americans how to prepare simple, delicious meals with what they had on hand. In this sense, the pandemic made high-quality dining less elitist. People made dinner with what they could get rather than exactly what they wanted. Gone were $40 entrees and wine pairings and Michelin-starred restaurants and reservations made weeks in advance; they’d been replaced by easy braises, homemade breads, and fried rice—or lesser concoctions made of whatever the grocery store still had in stock.

Meanwhile, aerial videos circulated on social media of lines of cars waiting outside food banks, sometimes stretching for miles down streets and highways. Boxes of groceries were hurriedly delivered out to their open trunks so as to minimize contact between people.

The biggest issue wasn’t the total food supply. Instead, the breakdowns came in transportation and logistics. Early in the pandemic, large quantities of products intended for schools, restaurants, and businesses had to be discarded. Producers that had contracts with large corporations and educational systems only had the capacity to package their food in bulk. Without direct-to-consumer models in place, they struggled initially to get their goods onto grocery store shelves. Some of the nation’s biggest dairy consumers, such as schools and coffee shops, were no longer operational, but dairy cows must be milked regardless, and perishable goods can only be stored for so long or allowed to take up so much space. Although some producers were able to donate these surplus items, large quantities had to be thrown out. As The New York Times reported in April 2020, “the costs of harvesting, processing and then transporting produce and milk to food banks or other areas of need would put further financial strain on farms that have seen half their paying customers disappear.”

But there was still something jarring about watching people line up at soup kitchens while suppliers mere miles away destroyed ample foodstuffs. It was, in fact, not dissimilar to scenes during the Great Depression of dairy farmers destroying thousands of gallons of milk, produce left to rot, and government culling hog populations and burying their carcasses in ditches in an effort to drive up prices, all amid a backdrop of soaring joblessness and poverty.

In 2020, as restaurants and school cafeterias were forced to close, demand patterns changed dramatically. This in turn had a sizable effect on prices. Before the pandemic, eggs had hit record lows; they soared to more than $3 a dozen in April. For some goods, prices have collapsed. Dairy and meat farmers have been hit hard by a drop in exports, for example, and by storage limitations. This has led to yet another era of milk dumping and hog euthanization: For farmers who typically produce pork for use in restaurants, pigs are fed on a strict schedule to get to the ideal weight for slaughter. A pig that exceeds 250 pounds can no longer be processed by meat plants, leaving farmers in the lurch.

Since the pandemic came into public consciousness so suddenly, many of the grocery store shortages were just temporary shocks to the system, albeit scary ones. All at once, people realized they would need to rely on home cooking instead of going out to eat; they started buying a four- or eight-week supply of groceries at a time, instead of the typical week or two’s worth; they began to notice buzzy headlines about stockpiling and shortages, which bred a sort of herd mentality, similar to the stockups that happened when news of impending government rationing made its way onto the airwaves in the ’40s.

As with wartime rationing, most people weren’t in danger of going hungry. But they had to contend with disruptions in the availability of goods they were used to relying on and with impediments to their ability to make the meals to which they’d grown accustomed.

Grocery stores often place orders several months in advance, so there was a lag in adjusting to meet demand. Some pasta producers took stock of their top-performing varieties and shifted production to just those types instead of the vast array they were previously churning out. So in lieu of a grocery store shelf stocked with rigatoni, tagliatelle, fusilli, bucatini, and fregula, you might find one stocked with macaroni, spaghetti, and penne alone. And with workers getting sick in droves, meat processing plant capacity dropped off. So some plants moved to prioritize certain cuts of meat over others. The result was reminiscent of wartime rationing, when people were more easily able to access ground beef and offal than choice cuts of steak.

Yet virtually all of 2020’s shortages were short-lived. Distributors managed to sort things out pretty quickly absent government interference. Egg prices slid back to more reasonable levels. Distributors used to working with restaurants were able to divert parts of their supply to be packaged for supermarket sale. Grocery store buyers adjusted to the heightened demand for flour, including specialty types used to make pasta, bread, and pastries. Some restaurants, beholden to orders they’d already placed, converted their unused dining rooms into temporary bodegas or specialty food shops, allowing patrons to avoid crowded grocery stores in exchange for a bit of a markup.

From muddled mask guidance to hampered test-kit rollouts, federal health authorities mismanaged the pandemic in myriad ways. Yet despite the central planners’ incompetence, there was one small blessing: The government at no time resorted to interfering in the food supply.

Though supply chains initially choked in the face of suddenly changed circumstances, leading to long wait times for food delivery and in-store quantity limits like the kind I encountered last March, grocery shopping quickly returned to something close to pre-pandemic abundance. Private actors had to contend with rolling lockdowns and viral threats, but for the most part they stabilized and even expanded their operations to meet unexpected public needs.

Amid the disruptions wrought by an unexpected global pandemic—layoffs and pay cuts, kids suddenly unable to attend school in person, a mass shift to remote work—it’s practically a miracle that government officials didn’t try to seize control of the food supply in an effort to win back people’s trust or instill a sense of certainty. Doing so would surely have done the opposite: As the OPA experience showed, central planners inevitably struggle to ascertain what people need and when they need it. The last thing anxious Americans needed was a government overhaul of a system that had temporarily stumbled but was working overtime (quite literally) to regain its footing.

In April 2020, Amazon hired an additional 175,000 workers. Instacart hired another 300,000. Grocery delivery wait times that had clocked in at weeks in March were down to days or even hours by June.

In the process, these companies helped accelerate food and cultural trends that were already in motion. A year after the pandemic began, more people than ever are working from home and having stuff delivered to their doors. There are fewer brick-and-mortar retailers but more ghost kitchens—restaurant-style facilities designed for takeout rather than dine-in service.

The pandemic has reshaped the American culinary scene, just like rationing did during and after the world wars. Back then, people took to eating heart, tripe, kidney, and liver—marketed via government propaganda campaigns as sexier-sounding “variety meats.” The openness to offal didn’t last long once the war was over. But in the 1950s, partially as a response to the meat rationing of the ’40s, grills came to the fore, with juicy steaks signaling a reprieve from austerity and a return to the American way.

That same decade, Swanson debuted frozen dinners. For the many women who stayed in the workforce full-time, they were a welcome time-saver. The fussy meals that had characterized earlier decades fell out of fashion.

New foodstuffs arrived as well: cereal bars; sliced bread with additives that made it take much longer to go stale; the dehydrated cheese coating used on Cheetos and in boxes of mac and cheese; instant coffee; and Chef Boyardee canned sauce. Many of these innovations were developed by food scientists working to feed the troops but eventually trickled down to consumers as low-cost, time-saving items.

Pandemic Food and Beyond

So what will the pandemic leave us with? Some things will probably look silly in retrospect, like the scallion-snipping and the not-especially-economical sourdough obsession.

But there’s something primal about how people facing a pandemic tried to combat scarcity and cling to the things they could control, predict, or enjoy. “Almost all people…have practiced certain forms of economy in their day,” wrote M.F.K. Fisher in How to Cook a Wolf, her 1942 book on cooking with less. “Sometimes their systems have a strange sound indeed, after the thin days are past.”

For me, it was canned tuna. In the early days, I wanted to reduce trips to the grocery store. My husband, a New Yorker, has long appreciated deli salads in all their mayonnaise-laden glory, and we knew it would be some time until we could travel to eat them again. The cans of fish were cheaper than I had realized, and the allure of them lasting forever on the pantry shelf was too great a temptation to resist in my weakened emotional state. So I started making tuna salads. And I couldn’t stop.

I made some with pepperoncinis, others with capers. Some with three types of mustard, others with none. Roasted almonds on top, or toasted ramen noodles, or scallions. I shared the recipes with friends, and it all felt very vintage. With its canned ingredients, the tuna salad had a distinctive ’50s vibe. But it was delicious all the same.

Food is a way of marking time, and when time ceases to mean much at all or to be marked by anything other than case counts and death tolls and beloved restaurants going under, you’ve got to find some way to pass the days. After the tuna was the cannoli pound cake phase, and the Portuguese salted cod fritter phase, and the linguini with clams phase.

The coronavirus has taken a very real toll, which we’ll be adding up for years to come. It has surely affected our world in ways seen and unseen. Still, we’re lucky that fears of food shortages came and went. We’re lucky the supply chains proved strong and resilient, that the wonders of Amazon bent under our collective weight only temporarily. We’re lucky Washington never felt the need to take command of the food supply or to dictate what we could buy.

“For centuries men have eaten the flesh of other creatures not only to nourish their own bodies but to give more strength to their weary spirits,” Fisher wrote. Our ability to cook and eat and break bread together has always been an essential part of defining who we are. The pandemic took much of that from us, but the grocery store workers and Instacart shoppers and Amazon delivery people have returned at least some of it, strengthening our weary spirits in a time of need—no government intervention necessary.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3cQhR9b

via IFTTT