The Chicago Teachers Union (CTU), as Robby Soave detailed this morning, is on strike this week over being asked to teach in schools. Last month, the CTU laid out its basic objection in one short if repetitive (and eventually deleted) sentence: “The push to reopen schools is rooted in sexism, racism and misogyny.”

This non-sequitur of an argument—why would racists advocate on behalf of educating a school population that’s 89 percent nonwhite?—has nonetheless been popular this past week among teachers unions and their supporters who oppose reopening schools on grounds of safety, even though the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has repeatedly stressed that (in the words of recently departed director Robert Redfield) schools are “one of the safest places [kids] can be.”

“Will We Let ‘Nice White Parents’ Kill Black and Brown Families?” asked the Chicago Unheard headline over a Jan. 24 piece (reprinted at Education Post) by public school teacher Mike Friedberg.

“The culture of white supremacy and white privilege can be seen in our very own community in regards to the decision to reopen schools in a hybrid format, despite rising cases and community spread,” wrote 140 members of the Pasco (Washington) Association of Educators Tuesday.

The Cambridge (Massachusetts) Education Association on Friday rejected school reopening plans while endorsing an Educators of Color Coalition letter that stated in part, “We have said repeatedly that the process the District has undergone, as well as the plans they have put forth for reopening, are rooted in white supremacy norms, values, and culture.”

The school-reopening debate after 320 days of some districts being shuttered is bound to be emotional and messy. We’re in the dead of winter, the pandemic death toll in the U.S. is rapidly approaching a half-million, businesses are on their last rubber band, and the vaccines for most people are still just out of reach. It is a season crying out for urgency, yes, but also grace. Which seems to be in short supply.

Like Chicago, Cambridge is an overwhelmingly Democratic-voting town. As are the New Jersey townships of Montclair, which this week saw unions pull the rug out from under school reopening, and nearby Maplewood, which last week finally reopened. A lengthy New York magazine feature this week about the fraught politics of those two New Jersey cases underscores something I have been writing about for the past year and a half: Politicians and public-education officials in staunchly progressive cities are using accusations of racism and white privilege in such a way that discourages public participation by any parents who may disagree with their policies.

April Mason, a public-relations professional, told New York reporter Andrew Rice that she was hesitant to speak up about reopening schools: “I’m a liberal, and I didn’t want to make a lot of noise about this issue. It was almost like this whisper campaign.”

Rice, who lives in Montclair, paints a scene of professional-class lefties walking on eggshells, in part for fear of being tarred as Trumpy and racist:

For months, the parents’ conversations about the issue had been mumbling and conflicted….Some social-justice activists, who have an outsize influence in the community, were apt to say that anyone who discounted the risks of COVID-19, which has brutally impacted Black families, was speaking from a position of privilege. No one wanted to alienate their children’s teachers. No one wanted somebody to die. No one wanted to sound like Trump. […]

“I still get called a granny killer,’ says Maya Ziobro, a parent who supports reopening. ‘If we say anything about wanting our kids to return to school, we’re painted as Trumpers.”

This isn’t some kind of white paranoia. Rice quotes Rutgers communications professor Khadijah Costley White, founder of SOMA Justice, “a group of local volunteers working to promote racial justice and safe spaces for people of color,” thusly:

“You see all these mothers constantly using poor and abused kids as fronts for getting their own kids back in school,” White said. How many of them were outraged, she asked, at the disparities within the school system before COVID? Through her eyes, it looked as if many of the protesters were affluent suburban parents, demanding that the schools bend to serve their own needs, as usual, while wishing away the deadly reality of the pandemic. “To me,” White said, “that doesn’t sound too different from the Trumpers.”

One of the reasons articles like these are such chalkboard-scratching exercises is that they illustrate how our degraded, Manichean national political discourse, in which opponents don’t just have a different preference for using government to solve a problem but literally want people to die, can, when grafted onto local situations, ruin personal relationships and community goodwill.

It also demonstrates that the effect, intended or not, of increasingly deploying such radioactive phrases as “white supremacy” to describe routine disagreements, is to actively alienate those on the butt end of the accusation. People in positions of power in Democratic strongholds are growing accustomed to opposition melting away in the face of words like “racism,” “privilege,” or “Trump,” in no small part because the “Nice White Parents” that abound in such polities will be mortified to be labeled as part of the problem, not the solution.

There is an alternative path to both sides in such disputes. Don’t assume that the other wants to kill people. Use precision in arguments, especially when making grave personal accusations. Freely acknowledge error and the limitations of your knowledge. And if someone calls you the worst name you can bear, don’t whisper, don’t slink off: Laugh at them. And then come back twice as loud.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3abjSKM

via IFTTT

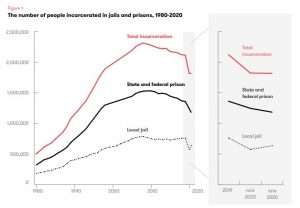

The Vera Institute’s report found that local jails drove the initial decline in incarceration, “although prisons also made modest reductions.” Prison populations continued to decline in summer and fall, but jails began to refill, the study found.

The Vera Institute’s report found that local jails drove the initial decline in incarceration, “although prisons also made modest reductions.” Prison populations continued to decline in summer and fall, but jails began to refill, the study found.