US equity index futures fell and the dollar rose after the latest Chinese data missed expectations and confirmed a sharp slowdown in the 2nd largest economy, while the spread of the coronavirus delta variant sparked worries the global economic rebound is faltering. Investors also awaited a town hall by Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell on Tuesday for clues on policy following a report from the WSJ that the Fed was weighing ending taper by mid-2022. As of 730am S&P eminis were down 12.50 or 0.28% to 4,450 after hitting an all time high on Friday; Dow Jones futures were down 101 points or 0.28% and Nasdaq futures were 42.75 lower. Commodities declined after Chinese retail sales and industrial output data showed activity slowed. Alibaba slid in premarket trading again after China’s state media criticized the online-game industry.

Alibaba lost 1.9% in early New York trading. China should tighten regulations of online games to ensure they don’t misrepresent history, state media reported. Here are some of the other notabl U.S. movers today:

- Cryptocurrency-exposed stocks rise with Bitcoin edging higher and holding on to recent gains. Riot Blockchain (RIOT) gains 2.5% and Bit Digital (BTBT) jumps 5.8%, while Marathon Digital (MARA) climbs 3.1% and Coinbase (COIN) advances 2%.

- Enlivex Therapeutics (ENLV) soars 22% after obtaining authorization from Israel’s ministry of health to initiate a clinical trial evaluating the safety and effectiveness of its Allocetra therapy on Covid-19 patients.

- Sonos (SONO) shares rally 13% in premarket trading after the home speakers maker won the first round of its patent case against Google and with Jefferies upgrading the stock to buy.

- Chinese large cap stocks listed in the U.S. fall in premarket trading on Monday amid another round of criticism from state media over online games. Alibaba (BABA) falls 2.1% and JD.com (JD) slides 3.1%, while Baidu (BIDU) slips 1.8% and Didi Global (DID) loses 2.2%.

While the world is transfixed by the chaos in Afghanistan, the biggest economic report overnight came out of China, where factory output and retail sales growth slowed sharply and missed expectations in July, as new COVID-19 outbreaks and floods disrupted business operations, adding to signs the economic recovery is losing momentum. Industrial production in the world’s second largest economy increased 6.4% year-on-year in July, data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) showed on Monday. Analysts had expected output to rise 7.8% after growing 8.3% in June. Retail sales increased 8.5% in July from a year ago, far lower than the forecast 11.5% rise and June’s 12.1% uptick.

According to Goldman, “the weakness reflects a combination of factors including the impact of past policy tightening, slower export growth, and a series of idiosyncratic shocks in July including a typhoon and major flooding in Henan province and the onset of the widest Covid outbreak in the mainland since early 2020.”

China’s economy had rebounded to its pre-pandemic growth levels, but the expansion is losing steam as businesses grapple with higher costs and supply bottlenecks. New COVID-19 infections in July also led to fresh restrictions, disrupting the country’s factory output already hit by severe weather this summer. Consumption, industrial production and investment could all slow further in August, analysts from Nomura said in a note, due to COVID-19 controls and tightening measures in the property sector and high-polluting industries. Production controls sent crude steel output to the lowest monthly level since April 2020 in July.

Meanwhile China tightened social restrictions to fight its latest COVID-19 outbreak in several cities, hitting the services sector, especially travel and hospitality in the country. “Given China’s ‘zero tolerance’ approach to Covid, future outbreaks will continue to pose significant risk to the outlook, even though around 60% of the population is now vaccinated,” said Louis Kuijs, head of Asia economics at Oxford Economics, in a note.

With Asian economies under stress from a resurgent pandemic and U.S. consumer sentiment near a decade low, investors are turning to signals from the Federal Reserve to sustain market momentum. A town hall by Chair Jerome Powell on Tuesday may act as a precursor to the Fed’s Jackson Hole symposium in late August, providing clues on whether a recent string of strong U.S. data qualified as adequate progress for the central bank to consider tapering stimulus.

“Shares remain vulnerable to a short-term correction with possible triggers being the upswing in global coronavirus cases, the inflation scare and U.S. taper talk,” said Shane Oliver, head of investment strategy and chief economist at AMP Capital.

In Europe, the benchmark Stoxx Europe 600 Index broke a 10-day streak of new record highs, with energy and commodity stocks the biggest drags on the gauge. Faurecia SE shares jumped 9.4% after the French auto supplier agreed to take over Hella GmbH in a deal that would create the world’s seventh-largest cap-parts maker. Mining stocks underperformed with metals prices coming under pressure from disappointing Chinese data. Stoxx 600 Basic Resources index down as much as 2.1% and hitting the lowest since July 28; Stoxx 600 benchmark down 0.6%. Heavyweights Rio Tinto, Glencore, Anglo American and BHP all lower and weighing on the index; steel company ArcelorMittal also falling. Antofagasta, Boliden and KGHM all lower as copper falls after Chinese industrial output data missed expectations. Here are some of the biggest European movers today:

- Faurecia shares gain as much as 11% after it agreed to buy auto- parts supplier Hella. Analysts note a smaller-than-expected equity raise and strong cash optimization among the positive characteristics of the deal.

- Ultra Electronics shares jump as much as 8.2% after Cobham made a firm offer to acquire the U.K. defense firm in a deal valuing Ultra at around GBP2.57b.

- LondonMetric shares rise as much as 2.2% to a record high after the U.K. REIT sold a Primark distribution warehouse in Northamptonshire for GBP102m.

- Naspers shares slump as much as 7.2% in Johannesburg, while Prosus drops as much as 5.6% in Amsterdam, following a slide in Chinese tech giant Tencent’s shares amid fresh worries over a regulatory crackdown.

- Lufthansa shares fall as much as 4.9% after Germany’s WSF stabilization fund said it would start to sell up to a 5% stake in the airline starting today.

- Orsted shares delcline as much as 2.6%. The wind farm operator is cut to neutral at Goldman

Earlier in the session, Asian stocks declined on Monday, with investor sentiment dampened by concern over the coronavirus and China’s disappointing economic data. The MSCI Asia Pacific Index fell as much as 0.8%, with Japan’s benchmarks leading the drop after the country extended states of emergency across six prefectures and amid an appreciating yen. The Hang Seng Tech Index slumped as much as 3% after China’s state media called for strengthened oversight of online games. Market sentiment continues to be weighed on by fear that the delta variant coronavirus spread will delay countries’ reopening plans. Figures released Monday by China’s government showed economic activity slowed more than expected in July, with fresh virus outbreaks adding risks to a recovery already hit by floods and faltering global demand. “The argument of ‘if people get vaccinated, everything will be alright’ is now wavering. If that falters, then it becomes harder to see when the economy might recover,” said Tetsuo Seshimo, a fund manager at Saison Asset Management Co. Mainland shares ended lower after the data releases, that included retail sales and factory output, while Philippine stocks were Asia’s top performers after a recent rout and Malaysia’s key index declined as the country’s prime minister resigned. South Korea’s stock market was closed for a national holiday.

Japanese stocks also fell, with the Topix dropping by the most in eight weeks, as coronavirus infection rates in Tokyo worsened and after the yen strengthened against the dollar. Electronics makers were the biggest drag on the benchmark, which fell 1.6%, with all but two of its 33 industry groups in the red. Fast Retailing and Recruit were the largest contributors to a 1.6% loss in the Nikkei 225. The yen extended its gain against the dollar after jumping 0.7% Friday. Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike warned Friday that the virus situation in the capital was at disaster level as cases jumped to a record of 5,773, more than quadrupling in just three weeks. Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga is poised to expand and extend for about another two weeks a virus state of emergency in Tokyo now set to expire at the end of August, the Sankei newspaper said. “Investors had expected that vaccines would help the outlook, but now things are uncertain,” said Tetsuo Seshimo, a fund manager at Saison Asset Management Co. “Even with vaccines, people are restricted in their activities, and it’s clouding the outlook for investors,” he said, adding that the Afghanistan situation is a global risk-off factor. Data on Monday morning showed Japan’s economy returned to growth, with GDP expanding an annualized 1.3% from the prior quarter, as consumer and business spending proved resilient

India bucked the trend, with its key equity indexes advancing to fresh peaks, led by Reliance Industries Ltd., as Saudi Aramco closed in on an all-stock deal to acquire a stake in the Indian company’s oil refining and chemicals business. The S&P BSE Sensex rose 0.3% to 55,582.58 in Mumbai, while the NSE Nifty 50 Index advanced 0.2% to 16,563.05. Reliance Industries Ltd rose as much as 2.7% and was the biggest contributor to gains for both indexes, driving them to new highs. Out of 30 shares in the Sensex, 14 rose, while 16 fell. The Saudi Arabian firm is discussing the purchase of a roughly 20% stake in the Reliance unit for about $20 billion to $25 billion-worth of Aramco shares, according to people with knowledge of the matter. The quarterly earning season for companies ended on Friday, with 29 of the 50 Nifty companies missing estimates. Of the remaining, 19 exceeded consensus, while two reported results in line with expectations

In FX, the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index inched higher and the yen and the Swiss franc led an advance among Group-of-10 peers while resource-based currencies such as the Australian dollar and Norwegian krone weakened. The Swiss National Bank appears to have intervened in the currency market to weaken the franc, with the amount of cash commercial lenders hold at the institution increasing by more than a billion francs for a second week running. Australia’s bonds gained and the Aussie dollar slid toward an almost one-month low after surging Covid cases led the NSW government to put the entire state into a weeklong lockdown; offshore sentiment was further weighed down by falling stocks and commodity prices. Japan’s sovereign bonds gained with the yen as a slump in U.S. consumer sentiment and weaker-than-expected Chinese data clouded the global economic outlook. The euro inched lower to around $1.1780 after rallying to a one-week high Friday; options traders are betting volatility in the euro will stay low and ranges will tighten further into year-end even amid the possibility of monetary policy divergence materializing between the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank. The pound traded little changed against the dollar and the euro ahead of inflation, labor market and retail sales releases later this week; leveraged funds increased bullish bets on the British currency, according to data from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission for the week through Aug. 10

In rates, treasuries were little changed in early U.S. trading after erasing gains that sent yields to lowest levels in at least a week, tracking similar reversals in German and U.K. yields, and rebounding U.S. equity index futures. Yields were mixed across the curve, within 1bp of Friday’s closing levels, the 10-year was flat at 1.277% after erasing a 3.2bp drop to 1.245%, lowest since Aug. 6. Coupon auctions ahead this week include $27b 20-year new issue Wednesday, $8b 30Y TIPS reopening Thursday.

Bitcoin traded around $47,400. Its second-day gain helped crypto stocks to rise in premarket deals. Riot Blockchain added 2.5%. Crude oil dropped for a third day as the resurgent pandemic hurt prospects for global demand.

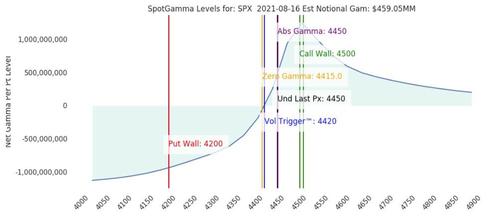

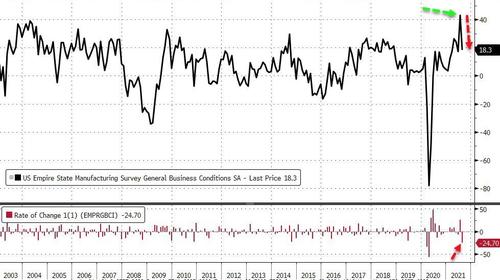

There is little on today’s calendar with the Empire Manufacturing Fed due at 830am, and the latest TIC data after the close.

Market Snapshot

- S&P 500 futures down 0.2% to 4,454.00

- STOXX Europe 600 down 0.5% to 473.46

- MXAP down 0.7% to 198.50

- MXAPJ down 0.5% to 653.16

- Nikkei down 1.6% to 27,523.19

- Topix down 1.6% to 1,924.98

- Hang Seng Index down 0.8% to 26,181.46

- Shanghai Composite little changed at 3,517.35

- Sensex up 0.3% to 55,617.10

- Australia S&P/ASX 200 down 0.6% to 7,582.46

- Kospi down 1.2% to 3,171.29

- Brent Futures down 1.5% to $69.53/bbl

- Gold spot down 0.2% to $1,776.21

- U.S. Dollar Index little changed at 92.56

- German 10Y yield rose 0.6 bps to -0.470%

- Euro little changed at $1.1787

Top Overnight News from Bloomberg

- China’s economic activity slowed more than expected in July, with fresh virus outbreaks adding new risks to a recovery already hit by floods and faltering global demand.

- Italy and Spain are set to record the fastest pace of economic expansion this year in more than four decades, a strong rebound that will help the countries overcome last year’s deep recession. Spain’s gross domestic product will expand 6.2% in 2021, while Italy will record a rate of 5.6%, according to a Bloomberg survey of economists

- Democrats are betting Republicans will blink and agree to raise the debt ceiling before it expires, a risky wager after a weeks-long standoff that threatens the health of the financial markets and continued U.S. government operations

- Bank of England policy makers are being overly-alarmist on their outlook for inflation, economists’ forecasts suggest, casting doubt on the need for a significant tightening in policy in the years ahead.

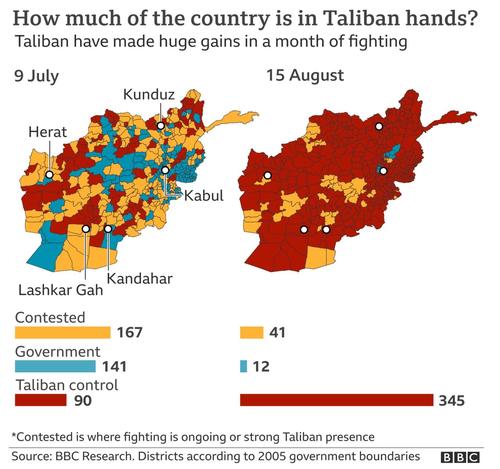

- Desperate scenes played out at Kabul’s international airport on Monday as thousands rushed to exit Afghanistan after Taliban fighters took control of the capital, with Reuters reporting at least five people were killed as people tried to forcibly enter planes leaving the country

- JPMorgan Chase & Co. says its decision to add the ESG tag to derivatives is part of a strategy to link sustainability to all forms of finance. The bank intends to replicate a novel cross-currency swap with Italian energy company Enel SpA, in which both parties need to meet specific ESG targets or face additional costs

- The thinking was that the pandemic would ebb and then mostly fade once a chunk of the population, possibly 60% to 70%, was vaccinated or had resistance through a previous infection. But new variants like delta, which are more transmissible and been shown to evade these protections in some cases, are moving the bar for herd immunity near impossibly high levels

- BNP Paribas requests traders to almost fully return to the office from October, Les Echos reported on Monday, without saying where it got the information

- Malaysian Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin and his cabinet resigned after more than 17 months in power, fueling a crisis of leadership in a country beset by a weakened economy and a surge in coronavirus cases

A more detailed look at global markets courtesy of Newsquawk

Asia-Pac stocks traded mostly subdued and US equity futures also pulled back from record levels due to ongoing COVID concerns and as participants digested disappointing activity data from China, while weekend newsflow was dominated by Afghanistan-related headlines after the Taliban effectively took control of Kabul which prompted a mass exodus of foreigners and embassy personnel from the city. ASX 200 (-0.6%) was led lower by weakness in energy and financials with the worst performers having recently announced their full-year results, while sentiment was also pressured by the ongoing COVID-19 situation that has forced an extension of lockdowns across several state capitals. Nikkei 225 (-1.6%) was the worst performer amid detrimental currency flows and with Japan likely to extend the state of emergency to additional prefectures as soon as this week after COVID-19 cases recently topped the 20k level for the first time which overshadowed the better-than-expected GDP data. Hang Seng (-0.8%) and Shanghai Comp. (+0.1%) traded mixed after Chinese Industrial Production and Retail Sales data both missed expectations with the stats bureau noting that the recovery remains uneven citing sporadic virus outbreaks and natural disasters. In addition, the PBoC announced a CNY 600bln MLF operation and although this was lower than the CNY 700bln of maturing MLF loans, the central bank noted that the liquidity released in last month’s RRR cut can partially repay the MLF, while the KOSPI remained closed in observance of Liberation Day. Finally, 10yr JGBs were higher amid the underperformance of Japanese stocks and similar gains in T-note futures as the US 10yr yield declined by around 5bps to breach the 1.2500% level. However, upside was capped for Japanese bonds after better-than-expected GDP data, while Economic Minister Nishimura stated that they are ready to take flexible action on the economy by tapping into JPY 4tln in reserves and will conduct flexible macroeconomic policy without hesitation to achieve sustained economic growth.

Top Asian News

- Chinese Stocks Listed in U.S. Drop Amid Online Games Criticism

- Asia Stocks Decline, Hurt by China Data Miss, Japan Selloff

- Afghanistan-Related Asian Stocks Drop as Taliban Retake Kabul

- China’s Faltering Economic Recovery Adds to Global Growth Risks

European equities (Eurostoxx 50 -0.7%) have kicked the week off on the backfoot in the wake of lacklustre Chinese data and ongoing COVID concerns. Chinese Industrial Production and Retail Sales data both missed expectations with the stats bureau noting that the recovery remains uneven, citing sporadic virus outbreaks and natural disasters. In Australia, sentiment was also pressured by the ongoing COVID-19 situation that has forced an extension of lockdowns across several state capitals, whilst Japan is likely to extend the state of emergency to additional prefectures as soon as this week. A lot of newsflow has centred around events in Afghanistan whereby the Taliban has taken control of Kabul which prompted a mass exodus of foreigners and embassy personnel from the city. However, the market implications at this stage remain unclear as the West ponders its response to events, if any. In terms of market commentary, JP Morgan notes, that Q1 and Q2 European reporting seasons have produced significant positive surprises, to the tune of 24% and 16%, respectively. Since January, consensus projected European EPS for the year has been revised higher by 16%, the strongest move on record. As such, JPM has set out new index targets, “looking for a further 4-7% upside into year end, with SX5E at 4500, on top of the already very strong 19% Eurozone equity return delivered ytd, ex dividends.” Sectors in Europe are mostly in the red with underperformance in Basic Resources, Travel & Leisure and Retail. Retail names are lagging post-Chinese Retail Sales with Kering (who account for nearly 30% of the Stoxx 600 retail index) lower to the tune of 1.8%, whilst LVMH is down 2.5% and Burberry sits at the foot of the FTSE 100 with losses of 2.6%. To the upside, Real Estate and Telecoms are the only sectors in positive territory. The notable individual outperformer is Faurecia (+8.7%) after agreeing to acquire the Hueck Family’s controlling stake in Hella (-3.0%) in a deal valued at EUR 6.7bln. Elsewhere, Deutsche Lufthansa (-3.2%) are lower on the session after the German Economic Stabilisation Fund said it will be selling a maximum 5% stake in Lufthansa over the next few weeks, accounting for around 25% of its total stake.

Top European News

- Turmoil in Afghanistan Adds to Geopolitical Risks Facing Markets

- EU Gas Climbs to Record as Flows Via Key Russian Pipe Fall Again

- Faurecia Gains as $8 Billion Hella Deal Reduces Engine Exposure

- Danske Senior Dealer Joins Fixed Income at AkademikerPension

In FX, safe haven flows see the DXY and JPY retaining their underlying bids caught since the deterioration in the APAC mood. Sentiment weakened as Chinese retail sales and IP missed the mark – and thus backed the notion of a slowdown in the world’s second-largest economy’s growth momentum. Further, geopolitical developments in Afghanistan have dominated the news, but it is too early to assess any near-term market implications. Meanwhile, the Yen may also see some tailwinds from the above-forecast Q2 GDP growth metric, although it’s worth noting the data may be stale as the COVID situation in Japan has worsened since the Tokyo Olympics – which kicked off at the start of Q3. The DXY sees mild gains after finding a floor around Friday’s 92.470 low and looks ahead to the NY Fed Manufacturing – which would mark the first August data point, whilst traders also keep tomorrow’s Fed Chair Powell appearance and Wednesday’s FOMC minutes in mind. USD/JPY has declined further below 110.00 and whilst taking out its 100 DMA (109.35) to the downside. The pair eyes mild support at 109.19 (2nd Aug low) ahead of the psychological 109.00. The CNH meanwhile has remained somewhat stabilised after overnight choppiness on the back of further evidence pointing to slowing economic growth momentum, but some observers expect China to negate these effects with looser policy. However, CNH bulls felt some reprieve after the PBoC conducted the MLF at a maintained rate of 2.95%, which adds to the likelihood of the LPRs being maintained later this week. That being said, reports last week suggested that any form of easing will likely take place in the RRR and interest rate. USD/CNH resides under just 6.4800 within a 6.4750-4815 range, with the 200DMA.

- AUD, NZD, CAD – The non-US dollars are all softer with the common denominator being risk sentiment. The AUD is the marked underperformer amid the disappointing Chinese data overnight, coupled with the ever-deteriorating Aussie COVID picture. That being said, the AUD/USD currently remains within the ranges seen in the past two sessions, with the 0.7333 proving to be formidable support. Some have been flagging AUD/JPY – a key APAC risk gauge – as the cross inches closer to 80.00 to the downside, dipping below 80.25 from today’s 80.87 peak. NZD/USD meanwhile is in the red but losses are cushioned in anticipation of an RBNZ rate hike later this week. Thus, the AUD/NZD cross has dipped below 1.0450 and continues to print fresh YTD lows as the cross eyes 1.0418 (2nd Dec 2020 low) ahead of 1.0400. The Loonie remains on the backfoot amid headwinds from COVID-suppressed oil prices, whilst the weekend saw Canadian PM Trudeau calling a snap summer general election on September 20th, some two years ahead of schedule – although a rebound in polls could pave the way for Trudeau to secure a majority government from the current minority. USD/CAD inches higher towards 1.2550 and its 200 DMA at 1.2565 as the Loonie looks ahead to July inflation data this week.

- EUR, GBP – Both the Single Currency and Sterling trade flat vs the Buck and against each other. EUR/USD tested but failed to breach 1.1800 to the upside whilst GBP/USD recovered from a 1.3837 base and once again makes its way to the 50 DMA around 1.3882. Analysts at ING note of a downside bias for the EUR amid a lack of firm bullish catalysts, with ECB-Fed policy divergence and summer trading conditions posing tail risks for the EUR/USD pair – “we could see the pair moving back to the lower half of the 1.1700/1.1800 range”, says the Dutch Bank. GBP meanwhile eyes a plethora of data including retail sales, employment and inflation, with traders eyeing indications to back the BoE’s upbeat outlook. EUR/GBP remains flat on either side of 0.8500.

In commodities, WTI and Brent front month futures remain subdued as the complex keeps an eye on the global COVID situation alongside the growth momentum slowdown experienced in the second-largest economy. Meanwhile, the situation in Afghanistan has grabbed all the headlines today as the Taliban overthrew the government, but from a market standpoint, the direct impact at the moment is too early to tell – but it’s worth keeping in mind that Russia, China and Iran have signalled an acceptance of the new government. Aside from this, traders will also be cognizant of the start of Hurricane season near the Gulf of Mexico (GoM), with Tropical Storm Fred set to make landfall around the Florida panhandle, whilst Grace reawakened to a Tropical Depression with the trajectory pointing towards the west of the GoM. WTI resides just north of USD 67/bbl after briefly losing the level (vs high 68.12/bbl), whilst Brent trades around USD 69.50/bbl (vs high USD 70.45/bbl). Elsewhere, spot gold trades with modest losses around USD 1,775/oz, but in a USD 10/oz range as the yellow metal balances a firmer Buck and softer yields. Base metals meanwhile are mostly lower across the board, with LME copper back under USD 9,500/t as the overnight Chinese data backs the notion of growth momentum slowing in the world’s largest copper consumer.

US Event Calendar

- 8:30am: Aug. Empire Manufacturing, est. 28.5, prior 43.0

- 4pm: June Total Net TIC Flows, prior $105.3b

- 4pm: June Net Foreign Security Purchases, prior -$30.2b

DB’s Henry Allen concludes the overnight wrap

Having just got back from two weeks away, I’ll be taking up the EMR from Jim over the next two as he departs on his own break of rollercoaster rides and golf courses. Like Jim, we opted to remain in the UK this year given the travel restrictions and spent a week in Cornwall, actually within walking distance of the recent G7 summit in Carbis Bay, which the geek in me was very excited to see. However, I was sadly the victim of multiple seagull attacks, the worst of which saw them steal an entire scoop of ice cream and leave a scratch behind my ear. Thankfully, the pharmacist said this wasn’t going to cause an infection, but to add insult to injury, the seagulls made a decent attempt at taking the replacement scoop as well. It seems as though capitalist notions of private property are yet to reach them.

Markets have faced no such obstacles while I’ve been away, with global equities ascending to a series of fresh records as investors gear up for next week’s all-important Jackson Hole symposium. Indeed, Europe’s STOXX 600 is up for 10 days in a row now, marking its longest run of consecutive gains since 2006, while an 11th advance today would make it the longest run since 1999.

Over the weekend however, the main news was in the geopolitical sphere as the Taliban reached the Afghan capital of Kabul and President Ashraf Ghani left the country. This follows a 3-week offensive by the Taliban that’s seen a major redrawing of the balance of power within the country, which leaves the Taliban set to take control two decades after their removal following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. On Saturday, President Biden said in a statement that he was increasing the total number of US troops in support of the evacuation of US personnel and the Afghans who assisted them to 5,000, and on Sunday multiple press outlets reported a US defence official saying that a further 1,000 on top of that would also be sent in. However, Biden’s statement also reiterated that he “was the fourth President to preside over an American troop presence in Afghanistan” and that he “would not, and will not, pass this war onto a fifth.”

For Biden, the developments in Afghanistan have created some unwelcome headlines just as further progress was being made on his economic agenda, with the Senate passage of the infrastructure bill with bipartisan support last week. Nevertheless, there was some potentially significant news on Friday as 9 moderate House Democrats threatened to withhold support from the $3.5tn budget resolution (which includes much of Biden’s proposals on social programs and climate change), unless the infrastructure bill were passed by the House and signed into law first. This is the reverse of what those on the progressive wing have said, which is that they won’t support the infrastructure bill without the budget resolution, which poses difficulties for the Democrats since their narrow margin of control means they can only afford to lose 3 votes in the House from their own side. In turn, Speaker Pelosi said yesterday in a letter to Democratic colleagues that she had requested that the Rules Committee “explore the possibility of a rule that advances both the budget resolution and the bipartisan infrastructure package”, so potentially moving them forward simultaneously. Since the Democrats’ control of the Senate as well is reliant on Vice President Harris’ tie-breaking vote, the decisions of individual members in both chambers over the coming days could be crucial as to the overall amount of spending that’s passed.

Overnight in Asia, the main news has been the release of Chinese economic data for July, which came in below expectations across the board. Retail sales grew by just +8.5% yoy (vs. +10.9% expected) while industrial production growth similarly underwhelmed at +6.4% yoy (vs. +7.9% yoy expected). Furthermore, fixed asset investment was up +10.3% yoy in the first seven months of the year (vs. 11.3% yoy expected), and the unemployment rate ticked up to +5.1% (vs. +5.0% expected). This downturn in the data comes on the back of recent Covid outbreaks that have led to further lockdowns and restrictions, and as a reminder DB’s chief China economist downgraded our GDP forecast for China in a piece out on Friday (link here), with the latest projections now seeing year-on-year growth of +5.5% in Q3 and +4.5% in Q4.

Amidst the weak data out of China, rising geopolitical risks and the continued spread of the delta variant, Asian markets are mostly trading lower this morning with the Nikkei (-1.89%), Hang Seng (-0.79%), Kospi (-1.16%) and Asx (-0.39%) all losing ground. Chinese bourses have fared somewhat better however, with the CSI 300 (+0.23%), Shanghai Comp (+0.37%) and Shenzhen Comp (-0.15%) holding their ground thanks to support from an overnight operation by the PBoC that saw the central bank roll over much of its medium-term policy loans coming due. Elsewhere, S&P 500 futures are down -0.25% this morning while yields on 10y USTs are down -3.0bps to 1.247%. Meanwhile there was somewhat stronger data from Japan, where their preliminary Q2 GDP came in at an annualised rate of +1.3% qoq (vs. +0.5% qoq expected), rebounding from an upwardly revised up -3.7% qoq in the previous quarter.

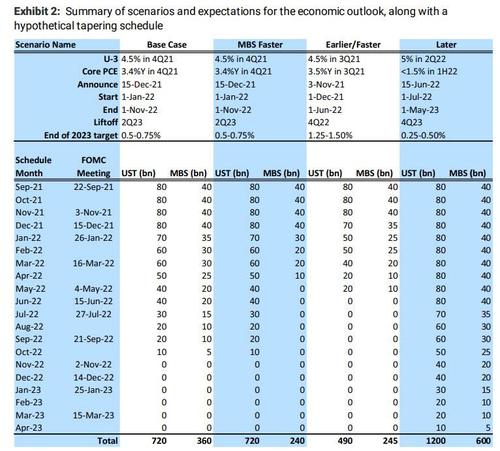

Looking forward now, the events calendar is relatively quiet over the week ahead as markets await the Jackson Hole symposium next week and Fed Chair Powell’s speech there for any signs on how the Fed might begin to taper their asset purchases. However, we will get the release of the FOMC minutes from their meeting in late July, which our US economists expect will provide more insights into the technical discussions around tapering strategies, and potentially some further clues as to which data releases officials will be focusing on as they assess progress towards their goals. We’ll also hear from Chair Powell in a virtual town hall with educators and students tomorrow, but that hasn’t traditionally been a forum for market communications.

Staying on the US, this week’s data releases will feature an increasing amount of hard data for July, including retail sales, industrial production, housing starts and building permits. On the retail sales release, our economists are expecting that auto sales will weigh on the headline number, and see a -0.6% decline this month. But they’re expecting a more mixed view on the factory and housing data mixed, with the manufacturing releases still pointing to strong production, whilst the housing sector continues to normalise around pre-covid levels of activity.

Turning to inflation, the coming week’s data should also add some further details on global price pressures after the US headline CPI print remained at +5.4% in July. The UK’s CPI reading for July will be in focus on Wednesday, particularly after the last couple of releases surprised to the upside and the Bank of England said at their latest meeting that “some modest tightening of monetary policy … is likely to be necessary” in order to meet their inflation target. Our UK economist projects that CPI will fall to +2.4% in July (vs. +2.5% in June), but still sees it peaking at closer to 4% before settling back down to target later next year. Separately in the Euro Area, there’s the final CPI print for July on Wednesday as well, and on Friday we’ll get the German PPI release for July, where the Bloomberg consensus is looking for a further increase after June’s +8.5% reading that marked the fastest rise in producer prices since January 1982.

On the earnings front, it’s nearly the end of the current season now, with over 90% of the S&P 500 having reported. Nevertheless, we’ve still got a few highlights over the week ahead, with tomorrow seeing reports from Walmart, Home Depot, BHP, and Agilent Technologies, before Wednesday sees releases from Tencent, Nvidia, Cisco, Lowe’s, and Target. Towards the end of the week, there’s also Applied Materials, Estee Lauder, Ross Stores, and Adyen on Thursday, before Friday sees Deere & Co release.

The pandemic will remain in focus over the week ahead, particularly given that cases have been rising at the global level for 8 consecutive weeks now, according to John Hopkins University data. In the US, the New York Times reported over the weekend that the Biden administration was drawing up a plan to offer booster shots as early as the autumn, with the story saying that priority would be given to care home residents, healthcare workers and the elderly. Meanwhile from today in England, those who’ve been fully vaccinated for two weeks won’t be required to self-isolate if they’ve been in contact with someone who’s tested positive for Covid.

Back to last week now, and global equity markets continued to inch up to new highs even as the daily moves became smaller. The S&P 500 rose +0.71% on the week (+0.16% Friday) with cyclicals such as banks (+2.15%) continuing to outperform, unlike technology and growth stocks as the NASDAQ lost ground (-0.09%) to finish just off the index’s record high. The S&P 500 finished at yet another record, its 48th this year, which is the most at this point of the year since 1995, whilst the VIX index of volatility fell -0.7pts to 15.5, having only closed lower on one occasion since the pandemic began. Amidst the cyclical outperformance, European equities rose to their own record close on Friday – its tenth in a row – as the STOXX 600 ended the week (+1.25%) higher.

Sovereign bonds gained slightly last week with US 10yr Treasuries rallying on the week following a -8.2bps decline in yields Friday that took the overall week’s move to a -2.0bps drop, leaving yields at 1.277%. Friday’s gains for Treasuries were due to the University of Michigan’s sentiment survey falling -11.0pts to 70.2 (81.2 expected), the lowest reading since December 2011 as inflation worries and concerns of the delta variant weighed on consumers. European sovereign bonds similarly gained on a weekly basis, with yields on 10yr bunds just -0.7bps lower whilst those OATs (-1.0bps), BTPs (-2.2bps) and gilts (-3.8bps) also fell.