While reading about the COVID-19 outbreak, you’ve probably encountered this particularly shocking statistic at one time or another: 80 percent of America’s pharmaceutical drug supply comes from China.

It’s a statistic that has made the rounds in right-wing publications for a while—offered as proof that China-heavy global supply chains are putting Americans at risk—but it has also popped up in mainstream outlets, including in pieces published in Politico and The Atlantic. Wherever it is deployed, the stat carries an unstated implication: What if China decides to cut us off in the middle of a pandemic? Could America face a dramatic shortage of key pharmaceutical drugs at the moment when we are most in need? And that distorted claim that says America has been too reliant on China has been seized by politicians like Sen. Josh Hawley (R–Mo.) as evidence that globalization has undermined America’s pandemic response.

In fact, because the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not track the volume of drug imports from any foreign countries, it is impossible to say with any certainty how much of America’s pharmaceuticals come from China. Or from anywhere else.

But that has not stopped politicians and media outlets from recycling this shocking statistic. That statistic is based on an inaccurate presentation of a single government report that says no such thing—and, in fact, suggests the opposite. At very best, it omits crucial context. At worst, it simply misleads. One expert who has repeated this stat in numerous publications and in congressional testimony refuses to share her source for that shocking bit of information.

The figure, in other words, is both misleading and mistaken. And the politicians and pundits who have seized on it have done so in order to make it seem as if they know with great certainty a supposed fact that no one actually knows.

II.

Tracing this “80 percent of American drugs come from China” claim back to its source reveals a game of “whisper down the lane,” in which a rather innocuous piece of data about the global manufacturing base for pharmaceutical drugs has been inaccurately summarized and stripped of important context.

In December, when the U.S. and China signed the “phase one” trade deal—and when the coronavirus outbreak was still very much in the background—Politico published a story (with some reporting from the South China Morning Post) framed around the idea that “U.S. policymakers” were worried that China could “weaponize” its drug exports to gain leverage in a trade dispute.

The piece was designed to scare. “The U.S. relies on imported medicines from China in a big way,” authors Doug Palmer and Finbarr Bermingham wrote right at the top. “Antibiotics, over-the-counter pain meds and the stuff that stops itching and swelling—a lot of it is imported from China.”

How much is a lot? “In all, 80 percent of the U.S. supply of antibiotics are made in China,” they wrote, linking back to a press release from Sen. Chuck Grassley (R–Iowa).

But that’s not what the press release says.

Grassley’s statement was publicizing a letter Grassley sent on August 9 to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the FDA, asking them to conduct more inspections of foreign drug manufacturing facilities to make sure they meet American standards.

“Unbeknownst to many consumers…80 percent of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients are produced abroad, the majority in China and India,” Grassley wrote.

There’s the first bit of context collapse: the authors of the Politico piece merged Grassley’s “80 percent…are produced abroad” into “80 percent…are made in China.”

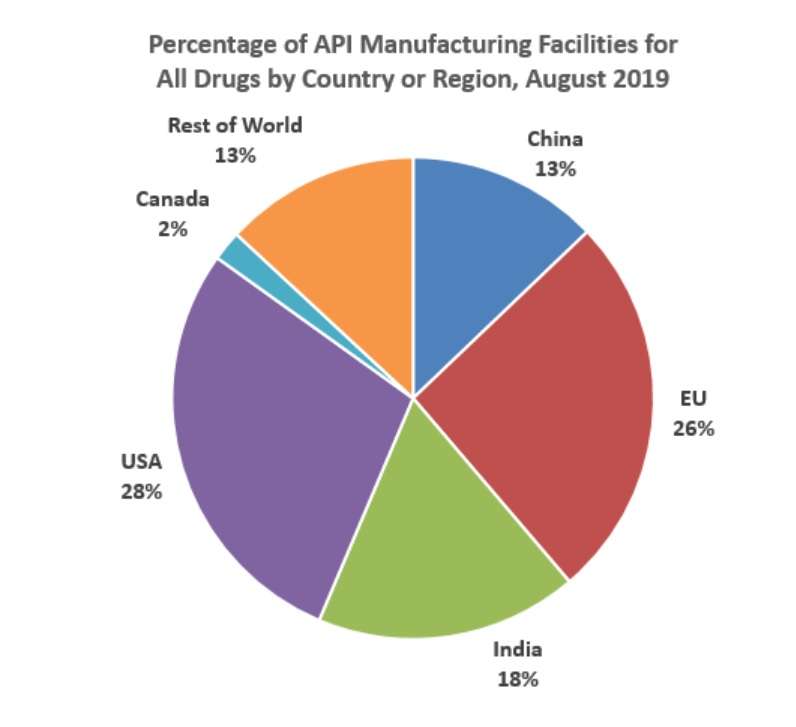

All of this also raises another question: Where is Grassley getting that information? His letter sources that claim to a 2016 Government Accountability Office report which itself cited FDA data on pharmaceutical manufacturers around the world. And that report makes it clear that the U.S. has a diverse supply chain for drugs that goes well beyond India and China.

“Nearly 40 percent of finished drugs and approximately 80 percent of active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) are manufactured in registered establishments in more than 150 countries,” is how the GAO summed up America’s pharmaceutical supply chain.

In two jumps, we’ve gone from “80 percent of American drugs are manufactured in more than 150 countries around the world” to “80 percent of drugs come from two countries” to “80 percent of drugs come from China.”

Now, a further complication. The FDA only tracks drug manufacturing facilities—not the supply chains of specific drugs.

That “lack of structural transparency and available supply chain data about drugs,” researchers at the University of Minnesota researchers wrote last month, is one of the reasons why making accurate assessments about potential drug shortages is difficult. Indeed, it was this same bit of missing information that Grassley was encouraging the FDA to address back in August.

It does seem like a reasonable thing to ask of the FDA. But for now, the lack of actual evidence means that no one can say with any certainty what percentage of America’s drugs come from which foreign countries.

The FDA’s most recent report on drug supply chains, published in October, makes clear that the agency does “not currently know whether API manufacturing facilities are actually producing the drug, or in what volume,” and therefore it is impossible to determine “what portion of U.S. drug consumption is dependent on APIs from China or India.”

That’s because many drug manufacturers make their products in various places around the world for reasons that range from the cost of labor to the availability of raw materials to access to consumer markets.

What the FDA does track, again, is manufacturing facilities that export drugs to America. In that October report, when the agency took its most recent statistical snapshot of the United States’ pharmaceutical supply chains, here’s what it found:

There are nearly 2,000 manufacturing facilities around the world that provide pharmaceutical drugs to the United States. Of those, 230 are in China. There are 510 in the United States and 1,048 in the rest of the world. Even though the number of manufacturers in the United States is at a historical low, the supply chain is clearly quite diverse.

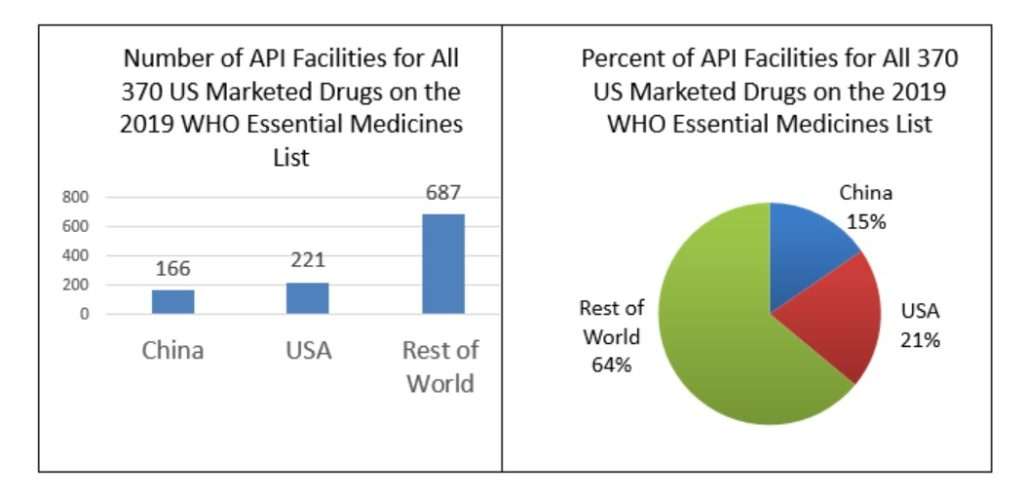

At the same time, the FDA took a narrower look at the supply chains for the 370 drugs listed on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) list of “essential medicines,” which includes “anesthetic, antibacterial, antidepressant, antiviral, cardiovascular, anti-diabetic, and gastrointestinal agents.” The results were similar: 21 percent of production facilities are in the United States, with 15 percent of them in China, and 64 percent located somewhere else in the world.

There are only three drugs on the WHO essential medicines list whose active ingredients are sourced entirely in China, the FDA found. They are capreomycin and streptomycin, which are used to treat tuberculosis, and sulfadiazine, which is used to treat trachoma, among other things.

Here’s another way to look at the question. According to the United Nations’ COMTRADE database of world trade flows, the United States imported more than $115 billion of finished pharmaceutical products in 2018, the most recent year for which complete data is available. Only $1.5 billion of that total came from China.

Nevertheless, Grassley’s letter and the underlying FDA data have been misinterpreted to give the impression that the U.S. is singularly dependent on China when the data actually show quite the opposite.

When Reason contacted the authors of the Politico piece, Palmer said he wasn’t sure why they’d linked to Grassley’s release.

“I don’t recall why we linked to that letter since it talk[ed] about API production rather than finished pharmaceuticals,” he wrote in an email. “It looks like a mistake. But it does express concern in Congress about U.S. dependence on China in the pharmaceutical sector.”

Unfortunately, that misinformation has fully entered the mainstream through other channels too. In a piece published in The Atlantic earlier this month, Uri Friedman notes that “about 80 percent of the active pharmaceutical ingredients in American drugs come from China and India,” and sources that information to a report from the Council on Foreign Relations.

And what does that report say? “It is believed that about 80 percent of the basic components used in U.S. drugs, known as active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), come from China and India, though the exact dependence remains unknown since no reliable API registry exists.”

Follow the link: It goes back to that same Grassley press release from August. Again, the article is inferring a conclusion that is not supported by the underlying data—and The Atlantic left out crucial context about lack of reliable information that was included in the Council on Foreign Relations’ report.

III.

Naturally, China hawks are seizing the misinformation, and the larger coronavirus crisis, to push for the confrontation they’ve wanted all along.

In that same Atlantic article, Peter Navarro, President Donald Trump’s top trade adviser, says the coronavirus outbreak should be a “‘wake-up call’ about American vulnerabilities in a globalized world.” Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who along with Navarro has been the driver of Trump’s crusade to raise tariffs and reduce U.S. trade with the rest of the world, has said the coronavirus outbreak might be a good thing because it will “help to accelerate the return of jobs to North America.”

In Congress, Sen. Josh Hawley (R–Mo.) has, unsurprisingly, taken the lead. “It is becoming clear to me that both oversight hearings and additional legislation are necessary to determine the extent of our reliance on Chinese production and protect our medical product supply chain,” Hawley wrote in a letter to the FDA in February. He called America’s supposed dependence on Chinese-made drugs “inexcusable” and appears to be laying the groundwork for some sort of pharmaceutical-industrial policy.

And at the center of that idea is a woman named Rosemary Gibson.

Gibson is a senior fellow at the Hastings Center, a nonpartisan bioethics research center, and the author of China RX, a 2018 book detailing “the risks of America’s dependence on China for medicine.” In recent months, she’s become the darling of right-wing media and politicians who see the coronavirus outbreak as an opportunity to ramp up a U.S.-China cold war. “All Our Drugs To Treat The Coronavirus Depend on Chinese Suppliers” noted a headline in The American Conservative on February 17 in which she argued that “we depend on China for 80 percent of the core components” that go into U.S. drugs. She had used the same “80 percent” stat in a December 13 article too, both times without attribution. In the December Politico piece highlighting how policy makers were worried about China “weaponizing” drug exports, Gibson was the first expert quoted. “Medicines can be used as a weapon of war against the United States,” she warned.

On March 12, when Gibson was called to testify before the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, she argued that “The United States faces an existential threat posed by China’s control over the global supply of the ingredients in thousands of essential generic medicines.” Those generics account for 90 percent of the drugs used in hospitals and sold in drug stores she said.

That sounds bad. But how many of America’s generic drugs come from China? That would be 9 percent, Gibson said in the same testimony.

A bigger concern would seem to be India, which manufacturers 25 percent of America’s generic drugs, according to Gibson. India imports a large amount of the ingredients in those drugs from China, which helps to demonstrate why it’s so difficult to put a number on exactly how much of America’s drug supply comes from China. Global supply chains care little for national borders.

Still trying to get to the bottom of the “80 percent” claim, I called Gibson last month to discuss her research and recent congressional testimony.

I came away from the conversation with the sense that Gibson is motivated by a sincere belief that Americans’ health is put at risk by shoddily-made drugs often manufactured overseas and that the FDA is not doing enough to prevent problems—or to collect the necessary data to identify where those problems might be. After the past few weeks have put a spotlight on the agency’s bureaucratic malfeasance and myopia, it is easy to be sympathetic to such arguments.

Gibson says the FDA’s data about drug manufacturing facilities is “misleading” because the agency fails to track actual supply lines from where the first chemical compounds are produced to where active ingredients are assembled to where the final products are shipped. This is pretty much the only thing everyone can agree on: that the FDA’s data is severely lacking context. That context might show the true complexity of pharmaceutical supply chains that wrap around the world, or the China-dependency that has nationalists worried.

But when it came to the question of how she knows that America is thoroughly dependent on China, Gibson was less transparent. I asked about the statistics she’d used in her pieces for The American Conservative and in her congressional testimony. Where, I asked, did she find this data that not even the FDA is tracking?

“I asked very fine people with 150 years [of] experience in making drugs,” she said. “I went around the table. First person said, ’90 percent, conservatively.’ Next person said, ’90 percent.’ Next person said, ’90 percent.'”

I’m sorry, I interjected, but if you can just clarify for me: Who were you speaking too? Where was this?

“These are people I know who actually make generic drugs or their components,” she said. “They know the best place, or the only place, where you can get” the necessary components.

So if I wanted to confirm that information on-the-record, how would I find it? “No, you can’t find that,” Gibson said. “No. I haven’t seen that.”

We went around a few more times: Who is telling you this? Is there another on-the-record source—a study, a paper, anything—that says this? But the answer was always the same: No.

Eventually, it became clear that the data weren’t the most important thing.

“Let’s put it at 90 percent of the chemical and other ingredients needed to make components—needed to make our generic drugs—are sourced from China,” Gibson said. “And if you want to…say it’s 75 [percent], that’s fine.”

But, hold on, doesn’t that distinction matter? Is the answer just that we don’t know?

“Well, what we do know is it’s enormous. Huge,” she said. “This is what they said: ’90 percent, 90 percent, 90 percent.'”

Who said?

“These are very seasoned people who have worked in manufacturing. It’s like the best chefs. You’re asking the best chefs ‘I need cinnamon or I need turmeric or mace or nutmeg. Where does it come from?'” she said. “They know that, but it’s not going to be written down in a book.”

(Cinnamon is exported by lots of countries all around the world —places as diverse as Madagascar, the Netherlands, and Vietnam. And those numbers are indeed written down.)

To be fair to Gibson, it is frustrating that the FDA does not track this information. But that’s no reason to substitute speculation for fact. And it is certainly possible that Gibson has sources providing this data point to her. But her unwillingness to identify those sources should be enough to make observers question the conclusions she is drawing from them. At the very least, you might expect Congress to want to hear this information firsthand from one of her sources.

And if the information is coming from industry insiders, as she suggests, and if they are as worried as Gibson says they are, one is left to wonder why they don’t do the prudent thing and shift their supply chains. No one is forcing them to manufacture in China.

But soon, someone might be forcing them to manufacture here. Whether the sourcing is sincere or not, there’s little doubt that Gibson’s research has become a tool for China hawks like Hawley, who blasted out excerpts from her March 12 testimony in a press release announcing his introduction of the Medical Supply Chain Security Act. Hawley says the bill would give greater authority to the FDA to get information from drug manufacturers about where they source ingredients, including raw materials, “and any other details the FDA deems relevant to assess the security of the U.S. medical product supply chain.”

That basic idea was incorporated into the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), the massive $2.3 trillion stimulus bill passed by Congress and signed by Trump last month. Under section 3010 of the law, HHS is directed to asses “the dependence of the United States…on critical drugs and devices that are sourced or manufactured outside of the United States.” Regardless of what the fact-finding mission might uncover, in another part of the bill Congress has already directed the department to include in its report “strategies to…encourage domestic manufacturing.”

It’s a telling bit of legislative text. In one fell swoop, Congress admitted that the federal government is ignorant about the extent to which drug supply lines are dependent on China—so much for that 80 percent figure that’s been repeated so much—and simultaneously announced its plans to change how those supply chains work.

What might those changes look like? In her testimony on March 12, Gibson outlined a few ideas. She wants the federal government to be intimately involved in process of manufacturing pharmaceuticals, covering capital costs for drug companies to build out manufacturing facilities “for domestic production of essential generic drugs and their core components” and controlling drug pricing to ensure that companies were making only “a fair rate of return” off the federal investment.

“Any federal investment in assuring essential generic drugs should be considered a national security asset that cannot be sold to companies whose governments are strategic competitors to the United States,” says Gibson. “This investment will help reinvigorate the U.S. generic manufacturing base and the capacity for the United States to eventually achieve a minimum level of self-sufficiency in the making of essential medicines vital to the nation’s health security.”

Tim Morrison, a senior fellow at the nationalist Hudson Institute and former member of the Trump White House’s National Security Council, told lawmakers at the same March 12 hearing that the federal government must intervene to prop-up domestic pharmaceutical suppliers. “The term ‘industrial policy’ is considered by some economic theorists and purists to be dirty words,” Morrison said. “I ask you to think about all of the tools of economic statecraft you can use to support American producers in strategic industries.”

Whatever comes next, it is likely to be a bipartisan process. In an op-ed for The Washington Post last year, Reps. Anna Eshoo (D–Calif.) and Adam Schiff (D–Calif.) cited the “80 percent” stat without proper context and linked to Gibson’s research to argue that “China has a virtual monopoly on the ingredients required to manufacture critical medicines.”

IV.

Bad facts make bad laws. Add into the mix a crisis and already high anti-China fervor within some segments of American politics. Whether due to context collapse—confusing all drug imports with drug imports from China, as some publications have done—or a panic-driven response to an unprecedented public health crisis, it appears that Congress has already decided to pursue a policy response based on theorized potential drug shortages that have yet to materialize.

“Instead of trying to get the FDA to figure out if its 75 [percent] or 90 percent, the reality is we gotta have the capability to make some of this here because countries will shut their doors,” Gibson told me.

Will they? India cut export capacity by about 10 percent in response to the pandemic, but so far they are (thankfully) the exception rather than the rule. Initial fears that China would cut off exports of medical equipment in order to hoard supplies for their own battle with the coronavirus have proven to be unfounded.

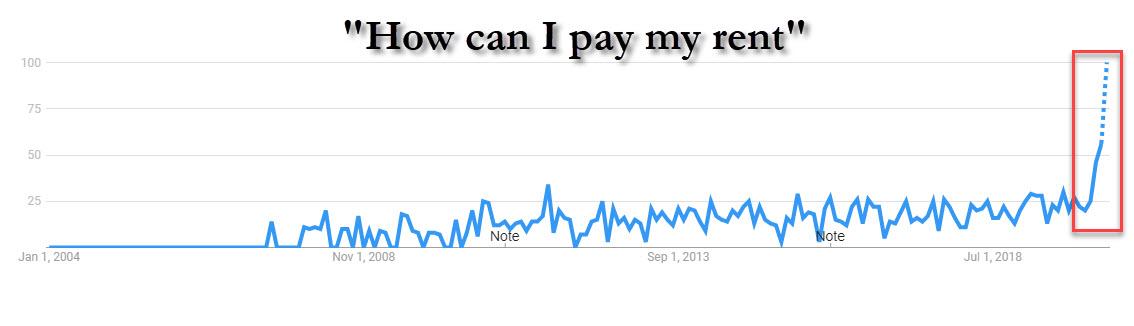

To the degree that drug shortages are likely to happen, experts say they will be the result of spiking worldwide demand—not countries cutting off trade.

“The pandemic itself may lead to increased demand for normal uses of certain drugs, such as acetaminophen to treat fever, and the crisis may also prompt hoarding,” researchers from the University of Minnesota warned in a study released last week. “In addition, drug production may be slowed or stopped in countries hit hard by the virus.”

Most drug companies are positioned to survive short-term supply shocks, J.P. Duffy, an attorney who specializes in the pharmaceutical trade, told European Pharmaceutical Review, a trade publication. That’s because most have a stockpile intended to last for six months to a year.

Like the University of Minnesota researchers, Duffy believes logistical problems are likely to be the cause of shortages—not political or manufacturing issues.

That’s why diverse supply chains are important, so that parts of the world unaffected by a major catastrophe can supply goods to areas more hard hit. The coronavirus outbreak may give some companies good reason to seek more diverse supply chains in the future. But it should not be seen as an argument for forcing pharmaceutical companies to make their products exclusively in the United States. Indeed, the question that policymakers should be asking isn’t “where do these drugs come from” but “can we be sure we’ll get them when they are needed.” Leave the specifics to the private sector.

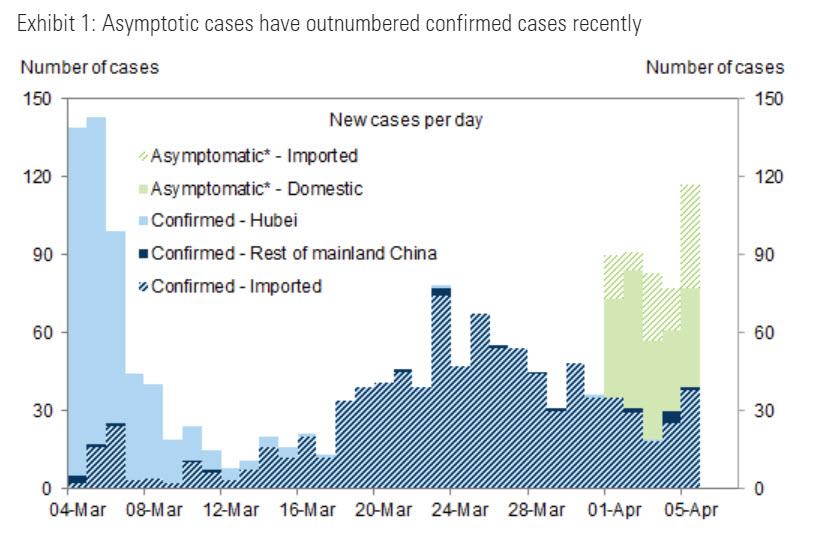

Even at the height of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, when many factories were shut down across the country, the Food and Drug Administration reported that America was facing a shortage of exactly one drug. After checking with the producers of more than 180 imported drugs to assess the state of their supply chains in the midst of the outbreak, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn released a statement saying that “none of these firms have reported any shortage to date. Also, these drugs are considered non-critical drugs.”

Meanwhile, the global supply chain for pharmaceutical drugs appear to be more diverse than the “80 percent from China” statistic suggests. There are only three drugs on the WHO’s “essential medicines” list for that the United States sources solely from China, according to FDA data. Chinese drug makers—while growing in recent years—account for only 13 percent of the global manufacturing base that supplies pharmaceuticals to America.

To be sure, there is plenty of space for American policy makers to criticize China’s handling of the COVID-19 outbreak. China’s leaders failed to communicate the seriousness of the disease at an early stage, and even now appear to be covering up the extent of the destruction the coronavirus has caused. There are documented cases of Chinese-made drugs failing to meet FDA standards that may call for greater scrutiny being applied to certain producers. The coronavirus pandemic may give some pharmaceutical companies a good reason to reconsider their supply chains.

But the fear that China would deliberately withhold drugs and other crucial equipment does not appear to be based on information that’s any more solid than the claim that 80 percent of America’s pharmaceuticals rely on Chinese suppliers.

There remains a big difference between fearmongering about China cutting off Americans from life-saving drugs and the reality of a pandemic that is stressing supply chains everywhere. The former serves as a call for political action. The latter, for simply letting markets work.

Whatever policies are crafted after the pandemic, they should be written with that context in mind—and with an awareness of the global reality of modern medicine. America’s supposed dependence on China has been overstated, but it does remain absolutely true that the United States imports most of the drugs that Americans consume. That, too, is an argument for keeping global supply chains open. It’s a reason for maintaining good diplomatic relations with other countries—not a reason to pursue autarky and continue an unnecessary trade war over fears that may not materialize.

“The world’s COVID-19 patients and medical experts need their policymakers to allow vital supplies and equipment to flow unimpeded from one country to another, wherever needed, as the crisis continues to evolve,” writes Chad Bown, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a trade-focused think tank. “Global cooperation is the only way countries can minimize the devastation COVID-19 is leaving in its path.”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2VcEdYK

via IFTTT