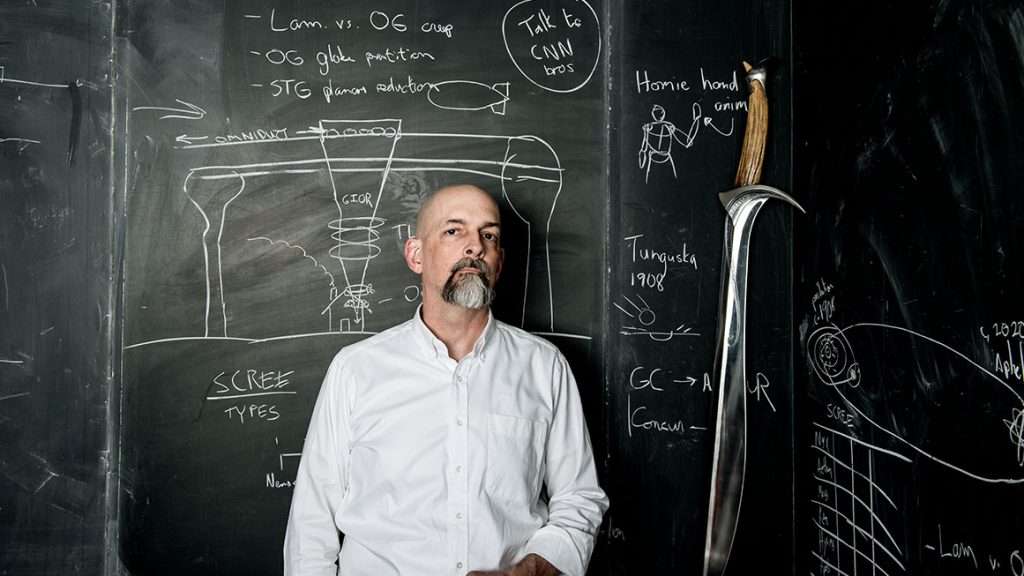

Neal Stephenson is the author of some of the most prescient and beloved science fiction of the last 30 years, including Snow Crash, The Diamond Age, Cryptonomicon, and Seveneves. His fiction deals heavily with economics, online culture, the history of philosophy, and the nature of money, with descriptions of bitcoin-like cryptocurrency systems appearing years before the technology’s real-world debut. His books frequently evince a skepticism of state power and an appreciation for decentralized technologies that will appeal to libertarians.

He’s also worked in the tech industry, serving as an early employee at Blue Origin, the private space firm founded by Jeff Bezos, and working with the Long Now Foundation to promote optimistic science fiction explicitly intended to inspire actual technological innovation. In 2014, he took a role as the chief futurist at Magic Leap, a pioneering augmented reality company.

Stephenson’s latest doorstopper of a novel, Fall; or, Dodge in Hell (William Morrow), is a not-quite-sequel to his 2011 book Reamde, a sprawling contemporary thriller set against the backdrop of a multiplayer online role-playing game built partially around the complexities of international currency. Fall picks up where the earlier book left off, with the story of Richard Forthrast, the game’s wealthy founder. It follows him into the virtual afterlife, telling a two-strand story set in both physical reality and a simulated environment. It’s part exploration of the legal and technological mechanics of radical life extension, part Dungeons & Dragons–style epic fantasy quest. Imagine a TED Talk on the singularity delivered jointly by Elon Musk and John Milton.

Fall is, in other words, a typically fascinating work by one of the most fascinating minds in fiction, science or otherwise. In June, Tyler Cowen, chairman of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, spoke with Stephenson about the current state of the economy, the future of technology, and how decentralized platforms have shaped the past and present of online culture.

Cowen: Let me start with some general questions about tech. How will physical surveillance evolve? There’s facial recognition in China that’s coming to many airports. What’s your vision for this?

Stephenson: I think it’s just going to be based on what people are willing to tolerate and put up with. There’s already something of a backlash going on over the use of facial recognition in some cities in this country, so I think people just have to be diligent, and be aware of what’s happening in that area, and push back against it.

Is there a positive scenario for its spread? Is it possible it will make China a more cooperative place, a more orderly place, and in the longer run they’ll be freer? Or is that just not in the cards?

I’m not sure if cooperative, orderly, and freer are compatible concepts, right? People who are in internment camps are famously cooperative and orderly.

Freedom is a funny word. It’s a hard thing to talk about because to a degree, if this kind of thing cuts down, let’s say, on random crime, then it’s going to make people effectively freer. Especially if you’re a woman or someone who is vulnerable to being the victim of random crime, if some kind of surveillance system renders that less likely to happen, then effectively you’ve been granted a freedom that you didn’t have before. But it’s not the kind of statutory freedom that we tend to talk about when we’re talking about politics.

Other than satellites, which are already quite proven, what do you think is the most plausible economic value to space?

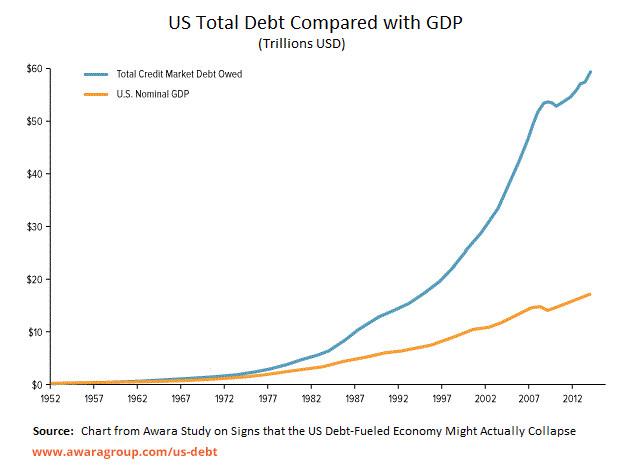

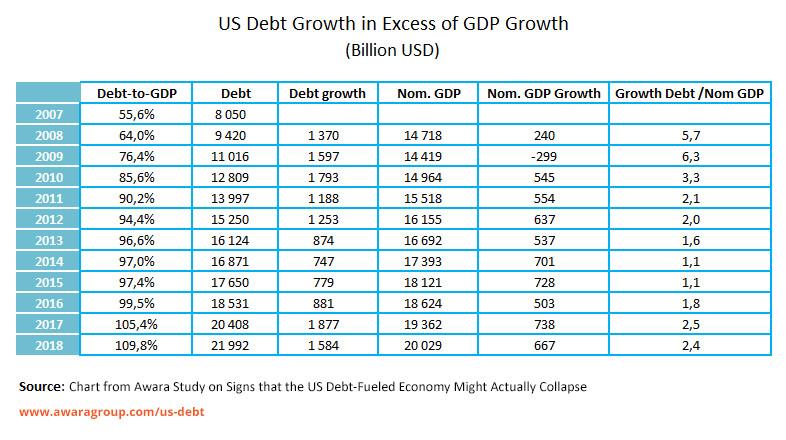

It’s tough making a really solid economic argument for space. There’s a new book out by Daniel Suarez called Delta-v, in which he’s advancing a particular argument. It’s a pretty abstract idea, based on how debt works and what you have to do in order to keep an economy afloat. But I think it’s a thing that people need to do because they want to do it as opposed to because there’s a sound business argument for it.

Do you think socially we’re less willing or able to do it than, say, in the 1960s?

Well, the ’60s was funny, because it was a Cold War propaganda effort on both sides. How that came about is a really wild story that begins with World War II, when Hitler wants to bomb London but it’s too far away, so he has to build big rockets to do it with, and so rockets advance way beyond where they would have advanced had he not done that.

And then we grab the technology, and suddenly we need it to drop H bombs on the other side of the world. So again, trillions of dollars go into it. And then it becomes so dangerous that we can’t actually use it for that. So instead, we use that rocket technology to compete in the propaganda sphere.

I once knew a grizzled old veteran of that ’60s space program who said that the Apollo moon landings were communism’s greatest triumph. So that’s how that all happened. And it happened way earlier than any kind of rational economic argument could be made for it, and I still think it’s the case that if we’re going to do things in space, it’s more for psychological reasons than it is for money reasons.

If we had a Mars colony, how politically free do you think it would be? Or would it just be perpetual martial law, like living on a nuclear submarine?

I think it would be a lot like living on a nuclear submarine. Being in space is almost like being in an intensive care unit in a hospital, in the sense that you’re completely dependent on a whole bunch of machines working in order to keep you alive. A lot of what we associate with personal freedom becomes too dangerous to contemplate in that kind of environment.

Is there any Heinlein-esque scenario—The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress—where there’s a rebellion, people break free from the constraints of planet Earth, they chart their own institutions, it becomes like the settlements in the New World were?

The settlements in the New World I don’t think are a very good analogy, because it was possible—if you’re a white person in the New World and you have some basic skills, you can go anywhere you want. And an unheralded part of what happened is that when those people got into trouble, a lot of times they were helped out by the indigenous peoples who were already there and who knew how to do stuff. So none of those things are true in a space colony environment. You don’t have indigenous people who know how to get food and how to get shelter. You don’t have that ability to just freely pick up stakes and move about.

In your books, you saw some of the downsides of social media earlier than most people did. What’s the worst-case scenario, and why do many people think they’re screwing things up?

I think we’re actually living through the worst-case scenario right now. I think our civil institutions were founded upon an assumption that people would be able to agree on what reality is, agree on facts, and that they would then make rational, good-faith decisions based on that. They might disagree as to how to interpret those facts or what their political philosophy was, but it was all founded on a shared understanding of reality. And that’s now been dissolved out from underneath us, and we don’t have a mechanism to address that problem.

But what’s the fundamental problem there? Is it that decentralized communications media intrinsically fail because there are too many voices? Is there something about the particular structure of social media now?

The problem seems to be the fact that it’s algorithmically driven, and that there are no humans in the loop making editorial, curatorial decisions about what is going to be disseminated on those networks. So it’s very easy for people who are acting in bad faith to game that system and produce whatever kind of depiction of reality best suits them. Sometimes that may be something that drives people in a particular direction politically, but there’s also a completely nihilistic, let-it-all-burn kind of approach that some of these actors are taking, which is just to destroy people’s faith in any kind of information and create a kind of gridlock in which nobody can agree on anything.

You have the idea of a smart book in your novel The Diamond Age. Do you think that will ever happen? There will be a primer that people use, and it’s online, and it will educate them and teach them how to be more disciplined?

A lot of different people have taken inspiration from The Diamond Age and worked on various aspects of the problem, and it’s always interesting to talk to them, because it’s sort of a classic “six blind men and an elephant” thing. I’ll hear from someone who says, “Oh, I’m working on something inspired by The Diamond Age,” and I ask them what that means to them, and it’s always a little different.

Sometimes it’s “How do we physically build something that could do what that book does?” Sometimes it’s “How do we organize knowledge, how do we set up curricula that are adaptable to the needs of a particular reader?” So I think it’s really not just one technology. It’s a whole basket of different hardware and software technologies, and people are definitely coming at that from various angles right now.

In your early novels, there’s a sense that states often have become quite weak. Do you think in reality that the state has stayed more powerful for reasons that are surprising? Or did you foresee it?

I certainly didn’t foresee anything. In Snow Crash and Diamond Age, I’m riffing on a way of thinking that I saw quite a bit among libertarian-minded techies during the ’80s and the ’90s that was all about reducing the power of nation-states.

If that was happening, I think it got flipped in the other direction, basically, by 9/11. When something like that happens, it immediately creates a desire in a lot of people’s minds to return to a more centralized, authoritarian kind of arrangement. And that’s the trajectory that we’ve been on ever since.

What will people wear in the future? Say, 100 years from now, will clothing evolve at all?

I think clothing is pretty highly evolved. I was ironing a shirt today in my hotel room, and it is a frickin’ complicated object. You take shirts, shoes, any kind of specific item of clothing you want to talk about—once you take it apart and look at all the little decisions and innovations that have gone into it, it’s obvious that people have been optimizing this thing for hundreds or thousands of years. New materials come along that enable people to do new kinds of things with clothing. But overall, I don’t think that a lot is going to change.

How bullish are you on bitcoin and cryptocurrencies? Do they have some kind of killer application? Or are they a novelty?

So far, it seems like they’re a bit of a solution in search of a problem. The nonmonetary applications of distributed ledgers seem to be more interesting than just making money. When people want to talk to me about a new cryptocurrency, I tend not to be super interested in continuing that conversation. But when they want to talk to me about using distributed ledgers to enable some other kind of initiative, then frequently it can get very interesting indeed.

It seems we’ve entered an age of permanent secular innovation starvation. Why did that happen?

There are a lot of institutional barriers that have arisen. A lot of it seems to be well-intentioned, but somebody was pointing out to me a little while back that the Golden Gate Bridge was built in a shockingly brief period of time compared to almost anything that we try to build today. Another good example would be the Hoover Dam, which went up in no time. It also killed a lot of people. So as we become more cautious about not killing people during a given project and not creating other bad side effects, that slows things down pretty radically, and there are institutional systems in place now most places to limit those kinds of bad side effects. So it’s kind of a mixed bag.

If someone says, “Well, tying everyone together with smartphones, and the fact that you can Google a piece of information within seconds—that was a big project. And we succeeded at it rather spectacularly. So there’s not actually innovation starvation.” What’s your response?

My general stance on it is that, yeah, when it comes to networks, computers, and so on, the amount of innovation has been unbelievable. It’s just been spectacular, and it’s because there’s so little friction. When you want to innovate in those areas, if you know what you’re doing, you can sit down and you can write some code and you can achieve great things just on your own or just with a small team. And then the cost of manufacturing and shipping that is basically zero, because bits are free.

So innovation in those areas is definitely amazing. But if you can’t do it in software, then things slow to a crawl, comparatively.

You focus on the Puritans in your trilogy of novels, The Baroque Cycle. Do you think Christianity was a fundamental driver of the Industrial Revolution and the scientific revolution, and that’s why it occurred in Northwestern Europe?

You focus on the Puritans in your trilogy of novels, The Baroque Cycle. Do you think Christianity was a fundamental driver of the Industrial Revolution and the scientific revolution, and that’s why it occurred in Northwestern Europe?

One of the things that comes up in the books you’re talking about is the existence of “out” communities that were weirdly overrepresented among people who created new economic systems, opened up new trade routes, and so on. I’m talking about Huguenots, who were the Protestants in France, who suffered a lot of oppression. I’m talking about the Puritans in England, who were not part of the established church and so also came in for a lot of oppression. Armenians, Jews, Parsis, various others. The minority communities that, precisely because of their outsider status, were forced to form long-range networks and go about things in an unconventional, innovative way.

I guess my answer is sort of cautiously yes, but maybe not in the way you’re thinking. It’s not the big, established churches that necessarily led to this. And it’s not Christianity, per se, because not all of these people were Christians. It’s the circumstances that made it possible for these weird outsider groups to find footholds in various niches and do new things.

Here’s a reader question: “The major Stephenson trope seems to me to be the single person or small group that is wise to tech or science, overcoming large, tech-based adversaries who are blind to their vulnerabilities, from the hero of Zodiac to the raiding team in Anathem, with many others in between. What is your theory of why large organizations are so bad at managing the low-level tech? Or is it just a literary device that does not hold true in practice?”

I think it’s largely the latter. It’s a great literary device, and it’s hard to write a compelling story about a giant organization, but it’s a lot easier to write one about a small group, where you’ve got different personalities interacting with each other and you get to know them as individuals. I think actual real-world examples of that happening are somewhat few and far between.

Now we’re going to do a segment where you tell us whether each thing is overrated or underrated. The first one is Leibniz as a philosopher.

I have to say underrated on the whole, mostly because of the backlash that he got from people like Voltaire, who didn’t get him, and Kant, who kind of took him down. I think he’s enjoyed a resurgence more recently, but definitely underrated in the couple of centuries after he died.

The Charles Dickens novel Bleak House.

I would say underrated, because it’s got just crazy, random stuff in it that you almost can’t believe that you’re reading it. There’s a character who, with no warning, just dies from spontaneous combustion. No explanation. It just happens.

Is Dickens an influence on you?

Oh yeah. He’s totally an influence, as a prose stylist and as someone who’s—I mean, we think of Victorian novels as a kind of stodgy old-school way of writing, but he was all over the map in terms of nutty, random things that he would put into his books.

The novels of Robert Heinlein. Are they still readable today, or are they simply of their time?

Well, they’re certainly of their time, but I find that, of all of the science fiction writers that I read when I was a kid, his stuff has stayed with me more than others. He had this knack for capturing little moments, little human interactions, and images that produced really vivid memories in my head that are still with me.

Morse code: overrated or underrated?

Currently underrated, I guess, because people aren’t really using it much, but very important in its time.

Which ideas or which areas of life do you feel are not sufficiently thought about?

People have a hard, hard time—even fairly educated, smart people have a really hard time—with statistical thinking and probability. A classic example is global climate change, where people have a hard time distinguishing between climate and weather. But that’s just one example. There are a lot of things that, really, the only rational way to think about them is in terms of statistics, but that just doesn’t come naturally to people.

When a society becomes more secular, as has been happening, what replaces religion for the average person, if anything?

Superhero movies.

And are those good, superhero movies?

Well, they’re not all good. But I seriously think that pop culture, like Lord of the Rings, is—

Neal Stephenson, perhaps?

Well, I don’t know about him. But Lord of the Rings, that whole world has become something approaching a secular religion for a lot of people. It’s not that they literally—well, some literally believe it—but even those who don’t [literally believe it] draw from it a lot of the same lessons and inspirations that a devout Christian might draw from reading the Bible.

In your new book, Fall; or, Dodge in Hell, what do you see as the implicit theology of that book?

It’s based on the question: Could it be the case that the world we live in is a digital simulation? This is something that people have pondered, and what happens in the book is that a new digital simulation is created, as a sort of digital afterlife, and it raises the question: Is it turtles all the way down? Are we living in a digital simulation, and creating our own digital simulations inside of it, and if so, how deep does that stack go?

What happens, when these dead people begin to create a virtual world to live in in the afterlife, is that they end up recapitulating a lot of the myths and the legends and the religious tropes that they dimly remember from this world. And so it gets to the question of, Do we have a psychological need for those things, such that when they’re taken away from us, we have to kind of rebuild them from scratch?

What do you think of the Bayesian argument that we probably are in fact living in a simulation?

Well, I’m not sure if it makes a difference. We’re definitely here either way, so it’s definitely an interesting notion. In a way, it’s the jumping-off point for Fall; or, Dodge in Hell. I also drew a lot of ideas from a book by David Deutsch called The Fabric of Reality, which talks about a number of things, but one of the things he talks about is how much computing power would be needed to simulate the universe that we see around us to a full level of fidelity, such that we never see glitches, we never see anything that’s imperfectly rendered. And he sort of heads in the direction of saying that it would take the entire universe to do that.

That’s in essence like the medieval cosmological argument that we’re all a simulation in the mind of God.

Yeah, so it’s that kind of recast in a more physics-based, computer science–based mold.

And if you were somehow convinced that was true, or thought it very likely to be true, would it change anything in your behavior?

I don’t know. A lot of this philosophizing can have the effect of pulling you back, zooming out from the day-to-day particulars of your life and thinking about things in a more detached and maybe calmer frame of mind.

Both philanthropy and the idea of being frozen, or held in suspended animation, are themes in the book. Is it a problem if there’s a future world where you’ve saved some assets, you freeze yourself in some manner and turn off for 400 years, and when you wake up you’re a mega-trillionaire? Is that a sustainable equilibrium, if a lot of people are doing it? Or is it a wonderful thing: We all get to be mega-trillionaires?

It gets to the question of excess wealth, in general, and what is it good for. We’re hearing now what we’ve all suspected, which is that wealthy individuals and corporations have amassed just enormous amounts of cash that, in a lot of cases, is just sitting around not doing anything, because you can only spend money so fast. Beyond a certain point, having more of it doesn’t really change your life. Even if you want to give it all away, you need to do that in a thoughtful and competent and accountable way, and that means you’ve got to find people that you can trust to handle that responsibility, and there aren’t enough of those people.

What’s the thing that’s getting worst socially?

Just the fragmentation. The thing we talked about earlier: People no longer having a common basis to have conversations with each other.

But is that kind of fragmentation really bad? If we can run a society on less consensus, because it somehow is more robust—say we all get transfers from a central authority, and then we each go our own merry ways, and we talk to people who are in our niche, but otherwise there’s no common conversation. Does that have to be so bad?

I guess we’re going to find out, because that’s where we’re going. It is an odd thing that we’ve seen the normal expectations of how the constitutional system of checks and balances is supposed to work, and the wheels have just come off in the last couple of years, and no one in a position of power seems to be capable or willing to do anything about it. Yet day-to-day life seems to go on without any obvious change. So you can read that as we’re in the calm before the storm and it’s all going to just collapse pretty soon, or maybe this is how things are now—D.C. is just a kind of sideshow, and it doesn’t matter.

Let’s talk about how you got to where you are. How did partaking in construction work help your writing?

By taking my mind off of writing for several hours a day. It’s an activity that requires focus and attention. You can’t just drift off while you’re doing it. So it occupies the “front room” of your brain for a while and allows interesting, creative things to happen in the back.

What would you do if you didn’t write?

I would probably have ended up working in some kind of tech company. I would probably have ended up writing code somewhere, and then over time I would have migrated into something that was a little more physical—actually building robots, or something that had code in it.

As a writer of speculative fiction, you almost certainly have a very large number of white male nerds as your fans.

It would appear so.

That aside, what do you think is a common element that binds a lot of your readers together, either demographically, or mentally, or emotionally?

It seems to be this desire and willingness to spend a lot of time in a big story world. I see a lot of people in the military who are readers of these books. I signed a copy of Snow Crash last night that had been around the world a couple of times in nuclear submarines. I’ve talked to people who read these books in Afghanistan. They’re big books. There’s a lot in them. So you kind of need to have the time and the willingness to sit back for a while and be immersed in order to enjoy them.

And what else do you think that’s correlated with—that desire to spend a lot of time in a story world?

People in tech. I think it’s just people who think about things, who have a kind of complicated inner life, and who derive satisfaction from reading big stories with lots of ideas in them.

Finally, what is it you think you’ll do next?

Writing-wise, I’ve got a couple of ideas that I’ve been working on for a while. What I need to do is go home and calm down. After my first book tour, I think it was six months before my eyelids stopped twitching. So I need to calm down, get back to normal, and then take a good look at this project I’ve been thinking about and figure out how to reboot it.

This interview has been condensed and edited for style and clarity. It has been adapted by permission of the Mercatus Center. For an audio version, subscribe to the Conversations with Tyler podcast.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2zS7QUZ

via IFTTT