Billy Steffey is determined not to eat the shot.

Steffey is a former federal inmate, and a “shot” is federal prison slang for a disciplinary infraction—as in, “They gave him a shot.” When you can’t dodge it, a shot is, like a punch in the mouth, something you have to eat.

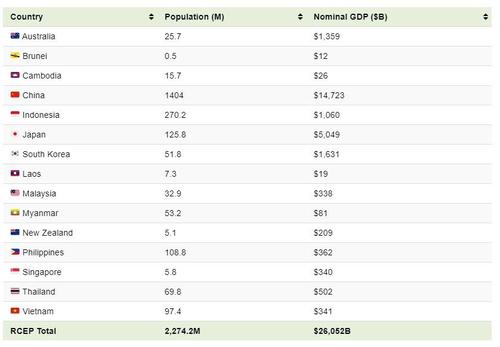

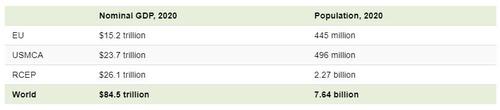

According to the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), Steffey conspired to smuggle drugs into prison in the form of a sheaf of legal papers laced with an illicit substance. The evidence against Steffey is a string of suspicious emails and two field tests, which you can buy off the internet for about $2 apiece, that came back “presumptive positive” for amphetamines.

Steffey is no longer incarcerated, but he is still trying to fight the BOP for stripping him of good behavior credits and throwing him in solitary confinement for five months based on what he says is an unverified test with a well-established track record of leading to wrongful arrests.

“It appears that the Bureau of Prisons regularly deprives prisoners of good conduct time credit, thereby lengthening their time in prison, based on a testing protocol known for its high rate of error, without even minimal procedures to ensure that the tests are conducted correctly and that questionable test results are subject to confirmation,” Steffey’s appeal to the 9th Circuit, filed last August, argued.

Incredulous readers may roll their eyes—prisons are full of both drugs and liars—but hundreds of botched cases across the country have raised serious concerns about law enforcement’s reliance on these types of test kits. Forensic experts say the tests can’t be relied on alone; they’re not admissible evidence in court; and the manufacturers explicitly warn that all tests should be sent to crime labs to be verified. New York’s prison system suspended the use of similar tests last summer because of such worries. Yet the federal Bureau of Prisons relies solely on such tests to put inmates in solitary confinement, take away good behavior credits that count toward early release, and strip them of visitation rights. Meanwhile, low evidence standards make it just about impossible for federal inmates to challenge the results of these tests in court. Steffey and other formerly incarcerated people say inmates are being jammed up on bad evidence with virtually no avenue for recourse. The BOP did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

The issues with these tests have been known for decades and are easily verifiable. Reason bought two packs of field drug tests and got positive results for several common, legal substances. But Steffey says the current system gives correctional officers an easy way to gin up shots against inmates.

“They don’t want to hear that, because it’s one of their tools that they have in their toolbox to get rid of people without question,” he says. “They give them a shot, they send it to [regional headquarters] and say, ‘Hey, we got to transfer this guy to a higher-security prison.'”

How the Tests Work, and Don’t

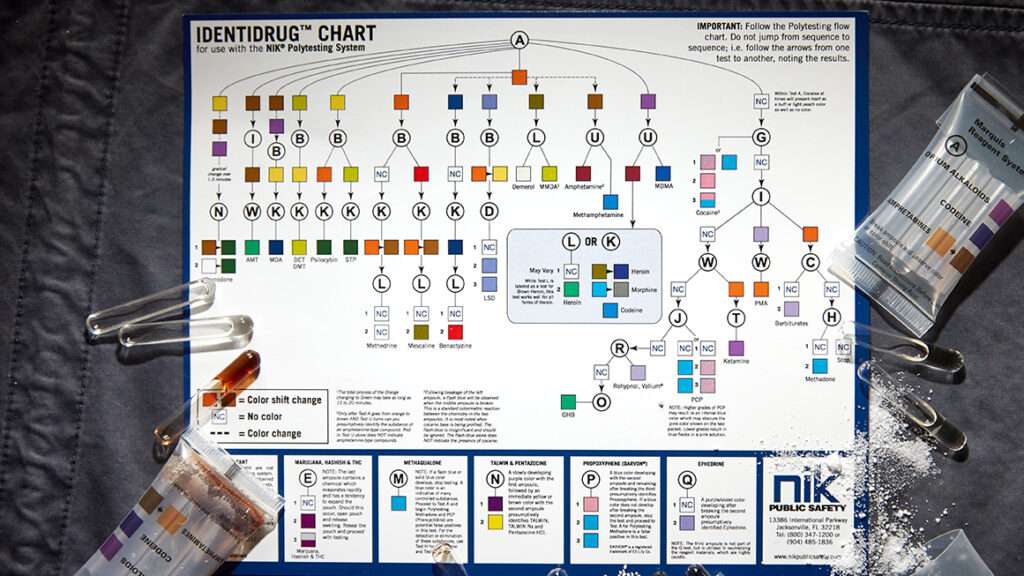

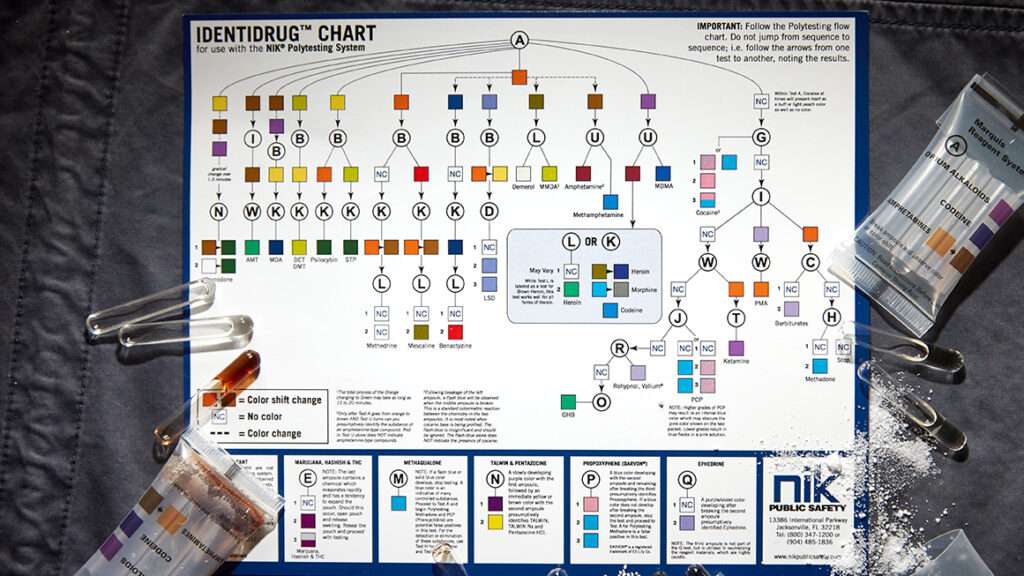

These test kits—plastic baggies with small glass vials inside—use basic chemical reactions to produce colors indicating the presence of various compounds. The user puts a small amount of the suspect substance into the baggie, cracks the vials, gently shakes, and watches to see what color results.

The Bureau of Prisons uses drug field tests manufactured by Safariland. Several companies make similar kits, but they all rely on the same underlying chemical reactions.

Heather Harris is an assistant professor of forensic science at Arcadia University who trains future chemists to use these color tests. “Atoms can combine together in groups—we call them functional groups—and these color tests are simply looking for the presence of a particular group,” Harris says. “When they find that group, they then proceed to go through a reaction that has a color as its product.”

A police officer or prison guard who comes across a suspicious substance could use Safariland’s NIK Test A, a general screening test that can turn a variety of colors, to see what the substance might be. If the clear liquid turns orange, then brown, the substance might be methamphetamines or amphetamines. The officer then moves on to NIK Test U, which either turns blue to indicate a presumptive positive result for methamphetamines, or burgundy. A burgundy result on Test U, in conjunction with the orange-brown result in Test A, is considered presumptive positive for amphetamines.

These tests alone aren’t admissible evidence in almost any court in the U.S., but they are considered probable cause for a police officer to arrest someone. And in prison, a “positive” field test can be enough to get inmates thrown in solitary confinement and stripped of other privileges.

The advantages of such tests for law enforcement are that they’re cheap, they’re portable, and they don’t require a chemistry degree to use. The disadvantage is that, as simple as the tests are, they’re far from immune to user error. The vials can be broken in the wrong order, for example. Colors are subjective. And the compounds that the tests screen for aren’t exclusive to the illegal drugs the tests are supposed to indicate.

“A methamphetamine test might be targeting a functional group that is present on methamphetamine,” Harris says. “That functional group, however, is not specific to methamphetamine. It’s common in the world, so there’s a variety of substances—some of which we know, but some of which we don’t know—that are going to possess this group and allow this color test to produce a color.”

Harris says the over-the-counter cold medicine Benadryl can produce positive results in field tests for several types of illicit drugs. And the list of known substances that can trigger a positive result in these tests is ever-expanding. Last year in Georgia, a college football quarterback was arrested after bird poop on his car tested presumptive positive for cocaine.

Reason bought packs of both NIK Test A and NIK Test U to experiment with. They can be easily purchased online, and they’re simple to use. Yet the results are up for interpretation.

A small piece of rosemary turned NIK Test A a light yellow-brown color, which could pass as a presumptive positive result if one really wanted it to. Coffee grounds also turned the solution in NIK Test A a dark brown, although it was unclear whether that was the result of a chemical reaction or just the color of the grounds themselves. Various types of paper seemed to have little effect on NIK Test A, though the solution turned the paper brown.

In addition, NIK Test U, the follow-up test for methamphetamines and amphetamines, turns burgundy when the ampule is cracked and shaken, regardless of whether anything is placed in the pouch. Steffey has put out a YouTube video demonstrating that a plain piece of paper will yield a burgundy result. This means that a presumptive positive for amphetamines in NIK Test A would be confirmed by NIK Test U by default.

This is not an error. Safariland’s instructions note that “only after Test A goes from orange to brown AND Test U turns can you presumptively identify the substance of an amphetamine-type compound. Red in Test U alone does NOT indicate amphetamine-type compounds.” The company did not return requests for comment for this story.

Steffey’s Story

In 2017, Steffey was serving a nine-year sentence at Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) Lompoc, a low-security federal prison in California, for his role in an online identity theft ring. He says it took him about four years to work his way down to that security level, and he was three months away from a possible transfer to a minimum-security federal prison camp. Although they’re not “Club Fed,” as tabloid headlines like to joke, the camps are as good as it gets in the BOP system.

“It would have been a night-and-day difference,” even coming from a low-security prison, Steffey says. “You get furloughs to go home and see your family. There’s a lot more freedom.”

Steffey says he got on the bad side of a couple of correctional officers, who began regularly searching his cell and generally making his life difficult.

In December of that year, a BOP mailroom staffer opened a package “of what appeared to be unfilled legal work” addressed to another inmate. The staffer noted that the papers felt “unusually thick” and gritty and looked discolored.

Contraband is a major problem for federal and state prison systems—especially synthetic marijuana, commonly called K2 or “spice,” and suboxone, a synthetic opioid. Inmates have figured out novel ways of smuggling the drugs in, such as lacing paper with liquid K2. The paper is then cut up into small pieces and smoked.

They smoke it “and then they flip out,” Steffey says. “They have seizures; get super high. They just do dumb shit. It’s a big epidemic in prison.”

To combat the flood of drugs, many state prisons have taken steps like banning physical mail and used book donations, which they claim are a major source of contraband. The BOP uses Safariland’s NIK field kits to check for suspected drugs.

A BOP investigator tested the legal papers addressed to the inmate with NIK Test A, the general screening test, and noted that it “had an immediate orange rapidly turning brown color, indicating Amphetamines,” according to court records. The investigator then tested another piece of the paper with NIK Test U, which “turned an immediate dark burgundy color, indicating Amphetamines.”

The investigator linked the package to Steffey after finding an email sent to him that included the tracking number of the package. BOP investigators also discovered a chain of email messages that appeared to be thinly veiled code about money transactions and deliveries.

Steffey says he was in fact having federal court records sent to another inmate, sandwiched between some blank divorce forms downloaded off a court website. The BOP submitted pictures of the papers as exhibits in Steffey’s lawsuit, but they are too low-resolution to read.

In prison, inmates often demand to see each other’s paperwork to verify what they’re in for and whether they’ve snitched. Prison has a strictly enforced social order, and sex criminals, especially those whose crimes involve children, are at the very bottom of it—shunned at best. So inmates sometimes run background checks on each other to make sure no one is lying. Getting another inmate’s paperwork in the mail isn’t allowed, but legal mail from an attorney is supposed to be privileged. Steffey says a contact of his was using a real lawyer’s name to send someone else’s court records to another inmate. He insists it had nothing to do with drugs.

“From Day One, I denied it,” Steffey says. “I was like, you guys are crazy. Let’s see the test. I’ll pay my own money to have it sent to a lab.”

Instead, a BOP disciplinary hearing officer found Steffey guilty of introducing contraband narcotics into the prison. The officer threw him in the Special Housing Unit (SHU)—a sanitized term for solitary confinement—for five months, where he was held in a cell for at least 23 hours a day.

“That was really tough on me,” Steffey says.

In 2011, a United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture concluded that solitary confinement beyond 15 days constituted cruel and inhumane punishment. But tens of thousands of incarcerated people in the U.S. are subjected to it for months, sometimes years, at a time.

The incident meant Steffey also lost any shot of going to a minimum-security camp. Instead, he was transferred to FCI Sheridan, a medium-security prison in Oregon. The BOP also stripped him of 41 days of “good time” credit for keeping a clean disciplinary record. There is no parole in the federal prison system, so accruing good time credit is one of the only ways that inmates can shave time off their sentences.

All of these steps were taken based on flawed physical evidence.

Safariland’s NIK kits, as well as those produced by other companies, aren’t supposed to be used on impure materials. Harris says the dyes and other chemicals in paper make it unreliable for color tests. “It’s just not designed to work that way. Right off the bat, when you have a piece of paper and you pull out your field test kit, you’ve made the wrong decision,” she says. “That’s not going to give you a reliable result.”

After he exhausted his appeals within the BOP bureaucracy—all denied—Steffey filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in federal court in January 2019. He argued that the NIK tests were being improperly used and requested that his good time credits be restored.

While his case was dragging through court, though, Steffey got an unexpected reprieve. In July 2020, he was among the thousands of federal inmates granted compassionate release by federal judges because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Field Tests Under Fire

Roughly two months after Steffey’s release, the New York Department of Corrections and Community Services (DOCCS) suddenly suspended use of drug field tests produced by another company, Sirchie.

“Effective immediately and until further notice, all SIRCHIE NARK II drug testing will be suspended and no misbehavior report will be issued, nor any adverse action taken against an incarcerated individual for suspected contraband drugs where a test is necessary,” a leaked DOCCS memo obtained by Gothamist read.

The New York State Correctional Officers & Police Benevolent Association, a union of state correctional workers, told local news outlets that DOCCS found there were false-positive results with the testing kits being used to identify contraband drugs. “Inmates who were penalized for contraband drugs have been released from special housing units and their records were expunged,” The Auburn Citizen reported last August.

A spokesperson for the DOCCS says the agency “is reviewing its current procedure for the testing of suspected contraband drugs. During this review, we have suspended testing. As part of the review, DOCCS is working with the Office of the Inspector General, and cannot comment further at this time.”

The New York Offices of the Inspector General declined to comment on the investigation.

Prison advocates are calling for a similar suspension of the use of NARK II tests in Massachusetts prisons after more than a dozen attorneys said they were falsely accused of sending drugs to their incarcerated clients, who were then put in solitary confinement for receiving legitimate legal mail. Unlike in the federal prison system, Massachusetts prisons send all field tests to outside labs for confirmation. This at least captures the bogus results, although it still leaves inmates to suffer in solitary in the meantime.

“That’s how [these tests] were integrated into forensic science in the first place, to be followed up with confirmatory tests,” Harris says. “The prisons have really gone off on their own to use it as this kind of one and only definitive test for whatever punishment or other purposes they’re using it for. They’re doing this outside of what I would say is the generally accepted use in the community.”

This is why Sirchie’s webpage for the NARK II test specifically warns, “NOTE: ALL TEST RESULTS MUST BE CONFIRMED BY AN APPROVED ANALYTICAL LABORATORY! The results of this test are merely presumptive. NARK® only tests for the possible presence of certain chemical compounds. Reactions may occur with, and such compounds can be found in, both legal and illegal products.”

Sirchie did not return requests for comment for this story.

Cotton Candy, Baking Soda, and Other Narcotics

Although police departments must rely on crime labs to confirm or invalidate field tests, that doesn’t stop innocent people from being arrested and jailed based on preliminary test kits.

In 2016, sheriff’s deputies in Monroe County, Georgia, arrested Macon resident Dasha Fincher after a search of her car turned up a plastic baggie of blue crystals. A NARK II field test of the substance returned a presumptive positive for methamphetamines, and Fincher was charged with trafficking and possession of meth with intent to distribute.

Fincher’s bail was placed at $1 million. She sat in jail for three months until a state crime lab determined that the -substance was exactly what Fincher had claimed it was when she was arrested: blue cotton candy. A follow-up investigation by a Georgia news station found that the NARK II test kit produced 145 false positives in Georgia in 2017.

Fincher sued the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office and Sirchie, but a federal judge dismissed the suit in May 2020. The judge ruled that Fincher hadn’t shown that Sirchie’s product was defective or that the company had failed to warn law enforcement officers of the tests’ shortfalls. And the judge ruled that because the deputies reasonably believed the tests they used were reliable, they had both sovereign and qualified immunity from Fincher’s lawsuit.

Similar cases abound. In 2016, an Arkansas couple spent two months in jail after a sandwich bag of baking soda in their truck tested “positive” for cocaine. “We tested it three different times out of two different kits to make sure that we weren’t having any issue, and each time we got a positive for controlled substance,” the Fort Chaffee police chief told a local news outlet.

A Florida man was wrongfully jailed in 2017 after a field test confused his donut glaze with meth. A 2018 drug seizure in North Carolina originally touted as “$2 million worth of ‘the deadly opioid fentanyl'” turned out to be white sugar.

In 2019, Reason obtained body camera footage showing a former Florida sheriff’s deputy arresting an innocent man after the deputy allegedly found methamphetamines in the man’s car. The footage shows the officer performing a NARK II test for methamphetamines, which turned dark red instead of blue, indicating a negative result, according to the manufacturer. That deputy has since been indicted on more than 50 criminal charges related to framing innocent people.

Some defendants—facing an extended stay in jail and threats from prosecutors about the sentences they’ll get if they turn down a deal—plead guilty to crimes they know they didn’t commit. Presumptive positive drug tests give the prosecutors leverage with which to pressure defendants in this way.

A 2016 ProPublica/New York Times investigation found that 212 people pleaded guilty between January 2004 and June 2015 to drug possession based on Houston Police Department field tests that were later invalidated by crime labs.

‘No Controlled Substance…Identified’

Outside of prison, those accused of drug possession based on a field test at least have some recourse to the criminal court system, where the high standards of evidence require presumptive positive field tests to be confirmed by crime labs. But inside, incarcerated people are at the mercy of bureaucracies even more strongly tilted against them.

Alberto Abarca, a former federal inmate, says he, like Steffey, was punished for drug contraband based on a bogus NIK test. In 2017, correctional officers at FCI Sheridan put Albarca and his cellmate, Carlos Vasquez-Maldonado, in the SHU and accused the two of possessing drugs in their cell. The guards had found an ink pen with a suspicious orange substance inside. NIK Tests A and U both came back “presumptive positive” for amphetamines.

Albarca says what the officers found was an empty Pilot G2 pen, and the suspicious substance was simply the stopper fluid that keeps the ink in gel pens from leaking or drying out. The fluid is typically grease or oil with other proprietary substances added to thicken it.

“I had been in the HVAC apprenticeship program for four years, and I was risking losing all that over this faulty NIK test kit,” Abarca says. “My cellie, we said, ‘Please, just send it to the lab. We’ll pay for it.'”

Although the BOP requires all positive urinalysis screenings for drugs to be verified by forensic labs, it has no similar policy for contraband tests. Courts have ruled that inmates have no right to demand independent verification of drug tests.

According to documents filed by the BOP in a 2019 lawsuit by Vasquez-Maldonado challenging his punishment, a BOP officer tested a fresh ink cartridge to see if a false positive resulted, but it did not. Vasquez-Maldonado’s lawsuit was dismissed.

Because the BOP does not require NIK tests for contraband to be independently verified, it’s impossible to say how often it happens, but Reason found at least one case where a federal inmate was punished based on the results of a NIK test that was later invalidated by a crime lab.

Brett Blaisure was incarcerated at FCI Beaumont, a federal prison in Texas. Blaisure practiced Wicca, and as part of his observance he wore a leather pouch around his neck with sage, frankincense, salt, and myrrh inside it. On December 4, 2014, he says, a correctional officer confiscated his pouch and tested its contents for drugs.

The disciplinary report says that using NIK Test A, Blaisure’s pouch “tested positive for Amphetamine.” The report makes no mention of NIK Test U, which is supposed to follow Test A.

As a result of the infraction, Blaisure spent 30 days in the SHU. He also lost 41 days of good time credits and had visitations suspended for nearly six months.

After he got out of solitary, Blaisure says he convinced BOP staffers to send the alleged narcotics to a local crime lab to be tested. After waiting six or seven weeks, he asked about the results. Blaisure says a BOP official told him, “‘Look, we’re not going to go with the lab results. We’re going to go with what happened in the office. We used NIK Test A, and it was positive, so don’t come bother us. Don’t come and ask us about it anymore. Your shot is staying the way it is.”

After spending two years going through the Bureau of Prisons’ grievance process and appealing his disciplinary sanctions, fruitlessly, Blaisure filed a petition in federal court in July 2016 seeking to restore his lost good time credits. (Federal inmates must exhaust their administrative appeals before they can file a lawsuit, and the exhaustion process often lives up to its name.)

When a federal judge ordered the BOP to respond to Blaisure’s claims, the government lawyer preparing the response found the nearly two-year-old results of the Jefferson County Regional Crime Laboratory’s test of the contents from Blaisure’s pouch: “No controlled substance or dangerous drug identified,” the lab had concluded.

“The whole time they had had a negative result from the lab saying that what I possessed was plant matter, period,” Blaisure says. “They had this paperwork and knowledge that I wasn’t allowed to possess for two years, and they made me suffer the consequences.”

The BOP disciplinary hearing officer submitted a sworn affidavit that he was unaware of the test. The BOP then expunged the violation from Blaisure’s record, making his lawsuit moot.

“I can’t even count how many people I saw that happen to,” Blaisure says of inmates being hit with bogus contraband accusations, “but I can guarantee you I’m one of the very few that I know of that took it all the way to federal court and won.”

‘All the Process Due Them’

Blaisure has reason to sound proud of beating the rap. Almost no one else ever does.

Courts give wide latitude to prisons to manage their daily affairs and security, and that extends to prison disciplinary hearings. In 1985, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Superintendent v. Hill that the BOP needs to show only “some evidence” to support a disciplinary sanction revoking an inmate’s good time credits—a far lower bar than both the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard that applies in criminal court and the “preponderance of evidence” standard used in civil cases.

“We hold that the requirements of due process are satisfied if some evidence supports the decision by the prison disciplinary board,” the Court wrote. “The relevant question is whether there is any evidence in the record that could support the conclusion reached by the disciplinary board.”

Lower federal courts, building on Hill‘s precedent, have held that a single positive drug test is sufficient to support disciplinary action; that those tests do not have to have a 100 percent confidence factor; and that inmates have no due process right to have those tests verified by an outside lab.

In 1989, a 4th Circuit Court of Appeals panel rejected an inmate’s argument that relying solely on unconfirmed positive results to impose sanctions violated the right to procedural due process. It ruled that the single field test afforded to many incarcerated people is “all the process due them under the Constitution and interpreting case law.”

Roger Terry, an inmate in a Maryland state prison, filed a lawsuit in 2011 after he was put in solitary confinement for nearly 200 days following a positive NIK test of coffee grounds that was later invalidated by a crime lab. Such is the majesty of the law that a U.S. District Court judge dismissed his suit, ruling that he had suffered no deprivation of due process or cruel or unusual punishment.

Some state courts have been more skeptical. In 2018, the Superior Court of Imperial County, California, ruled in the case People v. Chacon that unverified NIK tests were not admissible evidence in grand jury proceedings.

The court held a lengthy evidentiary hearing, where it became clear that the local district attorney’s office frequently used NIK test kits as evidence to obtain grand jury indictments, despite a number of innocent people having been indicted and clear warnings from Safariland that the tests should be verified.

“When confirmatory testing is done by the Department of Justice [in] some Grand Jury charged cases there turns out to be no controlled substances,” the court noted.

The testimony in Chacon also established that the term “presumptive positive,” as used by law enforcement and prosecutors, was largely meaningless, since the tests can’t discriminate between illicit substances and the dozens of known licit substances that also trigger color reactions.

“One of the many examples of the NIK testing errors was a case where heroin was identified using a NIK colorimetric test and a second Valtrox colorimetric test,” the court wrote in its ruling. “The substance was determined to be chocolate. So, if one were to accept the logic proffered by the People that the NIK heroin test is presumptive positive for heroin it would also be true that it is a presumptive positive test for chocolate. Likewise, if the NIK colorimetric test for methamphetamine is presumptive the same colorimetric test would be a presumptive test for ‘Equal,’ the sugar substitute. The NIK Color test for heroin does not meet any recognized forensic scientific standard.”

Testifying in the case, Allison Baca, a criminalist at the California Department of Justice, said that the agency does not use the term “false positive” when talking about color tests, because they do not consider such tests to be either positive or negative. The kits are screening tests that help the user determine what a substance might be.

And this is the rub of Steffey’s argument in his lawsuit. He isn’t saying that NIK tests are producing false positives—that is, incorrectly indicating the presence of drugs. He’s saying that the tests don’t provide reliable positive or negative evidence in the first place and that untrained BOP staffers are misusing and misinterpreting the tests.

Caught in a Bind

Unlike in Chacon, however, the federal district court that eventually heard Steffey’s lawsuit dismissed his case in May 2020 and denied his motion to hold an evidentiary hearing on the reliability of NIK tests. Without that hearing or additional records from the BOP, Steffey and his public defender weren’t able to put together a strong record to back up his appeal.

Federal inmates trying to fight NIK test determinations are caught in a bind: They have no procedural grounds to challenge their punishment as long as these tests are considered “some evidence,” but none of them can get far enough in court to challenge the validity of that evidence, even though there is an ample record to support their claims—including from the government itself. As early as 1978, the U.S. Department of Justice published standards for using drug field tests that advised the tests “should not be used for evidential purposes.”

Other law enforcement agencies have changed their policies over the last decade. In 2013, Travis County, Texas, stopped accepting guilty pleas for low-level drug possession before official crime lab results came in. The move followed the discovery of a dozen false positives linked to field tests. Harris County, Texas, and Portland, Oregon, did the same in 2016. The Houston Police Department discontinued the use of drug field tests in 2017.

As for Steffey, the grant of compassionate release that got him out of prison early also messed up his case, because the government was able to argue that he’d already received the relief he was seeking. He voluntarily dismissed his 9th Circuit appeal in December. But Steffey, still insistent on dodging the shot, says he plans on refiling the case as a civil rights lawsuit instead of a habeas petition.

The fact is, even if Steffey is lying about his own conduct, he’s right about the unreliability of these field tests.

“It seems like it would be simple enough to prove my case, but no one will listen because no one gives a fuck about what happens to inmates,” Steffey says. “But I promise you, it happens to people on the street too. I guarantee it.”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3wjGySY

via IFTTT