A new report released yesterday, by Richard Rosenfeld and Ernesto Lopez for the Council on Criminal Justice (CCJ), contains disturbing quantification of what has been reported anecdotally by media: Homicides have increased significantly in many cities across the country since late May. And the pattern across other crime categories documented in the report suggests that a “Minneapolis effect”—a reduction in policing similar to the “Ferguson effect”—may well be the cause for the recent spike in homicides.

The CCJ report looks at weekly crime data from more than twenty of the nation’s largest cities, including New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Atlanta, and Milwaukee. The report aggregates the data from these major cities and then looks for trends. With respect to homicide rates, the report concludes that:

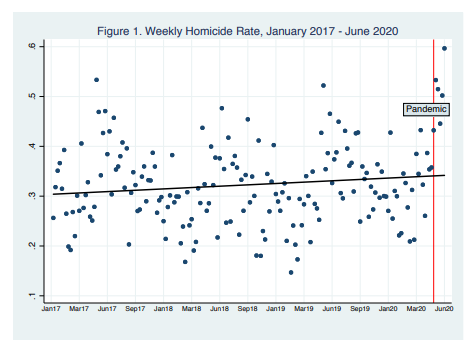

There appears to be a rough cyclical pattern and a very slight upward trend in the homicide rate over time. The model estimated a structural break near the end of May 2020, after which the homicide rate increased by 37% through the end of June. The rise in homicide was led by three cities: Chicago, Philadelphia, and Milwaukee.

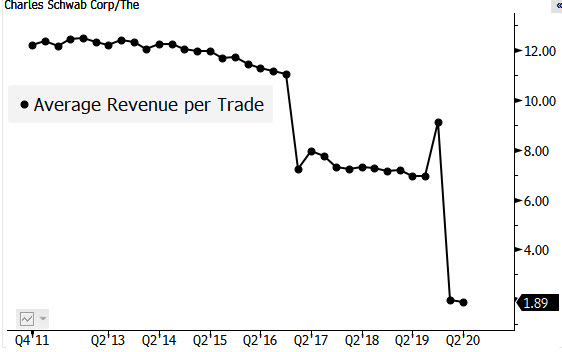

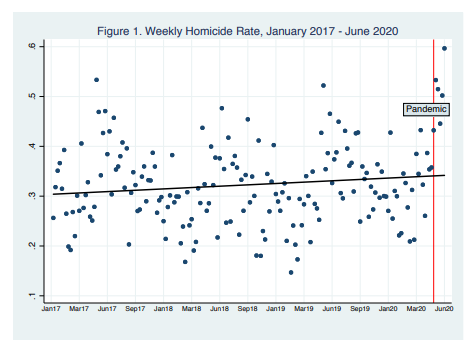

Here is the weekly homicide data depicted as a scatter plot.

The vertical red line indicates a “structural break” identified in weekly homicide rates between January 2017 and June 2020. (The structural break model assumed the break point was unknown and allowed the model to estimate the significant break in the series and adjusted for seasonal effects by comparing to crime rates during the same week in the previous year.)

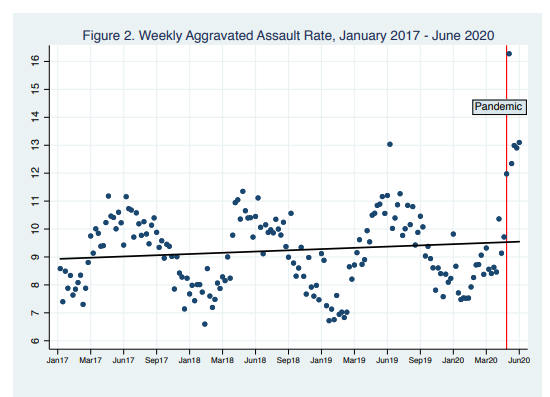

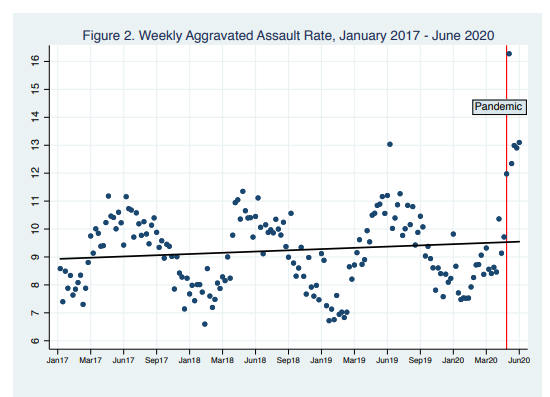

The report observes the same pattern of a recent increase for aggravated assaults. Looking at 17 large cities for which data were available, a structural break near the end of May 2020 was detected as well. Aggravated assaults rose by 35% from late May through the end of June 2020. The rise in aggravated assaults was led by Chicago, Louisville, Nashville, and Detroit.

Here is the weekly aggravated assault data depicted as a scatter plot:

Here again, the vertical red line indicates a structural break in the data set—a structural break that obviously exceeds ordinary seasonal variation.

What is noteworthy about the post-late-May spikes in homicides and aggravated assaults is that this same pattern does not appear for all other kinds of crimes. The report looked at nine other crime categories—gun assault (a subset of aggravated assault), domestic violence, robbery, burglary (and also the subsets of commercial and residential burglary), larceny, motor vehicle theft, and drug offenses. None of the other crime categories exhibited a structural break starting in late May. Burglaries, for example, abruptly increased (by 190%) at the end of May and then equally abruptly returned to normal levels in the next week. A dramatic increase in commercial burglaries in the week that coincided with the mass protests following the George Floyd killing explains this pattern.

The crime categories that came the closest to exhibiting the same pattern as homicides and aggravated assaults were gun assaults and robberies. Gun assaults also showed a sharp and sustained increase after late May, although the pattern was not clear enough to be identified as a structural break. And robbery exhibited a structural break, but the timing was slightly earlier. Robbery exhibited a long term downward trend, but after March 2020 the robbery rate rose by 27% through the end of June.

I have previously blogged about a recent and similar pattern in crime increases in Minneapolis. In that city, shooting crimes (including homicides) increased after the police killing of George Floyd in late May—but other crimes did not. A key part of the explanation appears to be that Minneapolis police stopped making as many street stops as they made previously. And given the unique responsiveness of gun crimes (such as homicides) to police activity, the result of the reduction in Minneapolis appears to have been a sharp increase in gun violence. At least 275 people have been the victims of gun crimes in Minneapolis during the first seven months of this year, surpassing the entire annual totals of all but two of the past ten years.

A parallel pattern of firearm crime increases occurred during the 2016 Chicago homicide spike. A detailed paper on the Chicago spike by my University of Utah colleague Richard Fowles and me explains that in Chicago in 2016 gun-related crimes increased dramatically, but not other crimes. (See pp. 1600-01 of the study). Specifically, in Chicago in 2016 homicides increased substantially, by 58% year-over-year from 2015 to 2016. There were also large (more than 20%) increases in robbery and aggravated assault–but not such large increases in other index crimes. Focusing specifically on gun crimes, there was a substantial increase in shootings in Chicago in 2016. Fatal shootings increased by 66% and non-fatal shootings increased by 44%. (See Table 5).

Professor Fowles and I explained in our paper that the most likely cause of the 2016 Chicago homicide spike was a reduction in street stops (often referred to as “stop and frisks”) in Chicago. We called this effect the “ACLU effect” because an agreement between the Chicago Police Department and the ACLU in in August 2015 was implemented in December 2015, leading in 2016 to about an 80% reduction in street stops conducted by Chicago police officers.

The new CCJ report discusses what might be causing the recent spike in homicides and aggravated assaults. The report notes that while some of the violence was directly connected to protest activities, in most cases the crimes appear to have involved perpetrators other than the protesters. Most of the increase in violent crime took place away from the demonstrations and was not limited to single week (such as the week surrounding May 25, when George Floyd was killed).

The CCJ report also finds it instructive to compare the recent rise in urban violence with the increases that occurred five years ago in the wake of protests about a police killing in Ferguson, Missouri. As the report explains,

Analysts tied the heightened violence to two versions of the so-called Ferguson Effect. The first connects the violence to “de-policing,” a pullback in law enforcement. The second essentially turns this explanation on its head and connects the violence to “de-legitimizing,” positing that communities, disadvantaged communities of color in particular, drew even further away from the police due to breached trust and lost confidence. As a result of diminished police legitimacy, fewer people reported crimes to the police or cooperated in investigations, and more engaged in street justice to settle disputes. It remains unclear whether either of these theories explains the previous rise in violence, much less today’s increase.

The CCJ report is properly cautious in concluding that we don’t know for certain whether de-policing or de-legitimizing policing was responsible for the increase in homicides and other violent crimes in 2015-16 … or which of the two is (apparently) responsible for the recent homicide increases since late May. But my prediction is that a de-policing “Minneapolis Effect” (akin to the earlier de-policing “Ferguson Effect” or the “ACLU Effect” in Chicago) will ultimately possess the most explanatory power for the recent and abrupt homicide spikes.

Here’s what the recent data appear to show: In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, police have been redeployed to respond to anti-police protests, diverting them from anti-gun patrols and other activities that deter the carrying of illegal firearms. Police have also also pulled back from some measures of pro-active policing, again as the result of the protests. The result of this reduction in law enforcement activity directed against gun violence has been, perhaps unsurprisingly, an increase in gun violence. Chicago Police Superintendent David Brown put the point precisely for his city, explaining that “[e]very time we have to drain our resources for protests, the people on the West Side and the South Side suffer.”

The de-policing hypothesis appears to be a better fit with the data than the de-legitimizing hypothesis. If law enforcement has become generally de-legitimized, the result should be a general increase in all crime categories, including (for example) burglaries. But that is not the pattern that the data exhibit. The recent data reflect an increase in homicides and other gun-related crimes but not other crimes—a unique pattern that is more consistent with de-policing being the cause.

One way of attempting to sort through the competing hypotheses is to examine whether residents of the affected citiies are reporting fewer crimes to the police. In analyzing the 2016 Chicago homicide spike, for example, Professor Fowles and I used calls to 9-1-1 as a measure of police legitimacy, as was suggested by other researchers. We found that changes in 9-1-1 call rates could not explain the Chicago homicide spike. Examining recent 9-1-1 call patterns might be one way to investigate any explanatory power of the de-legitimizing hypothesis.

Similarly, police departments often keep data on street stops and other measures of police activity. Changes in these activities should be assessed to see if they correspond to increases in homicides. For example, in my recent blog post, I pointed to a decrease in Minneapolis in police searches and suspicious person stops that coincided precisely with the increase in shootings that occurred there in late May. Data in other cities could be reviewed to see if they exhibit similar trends.

If the hypothesis about a Minneapolis Effect is correct, a recommended policy response would seem to be to bolster police activities targeting gun violence. Some modest good news on this front comes from Chicago. Last week, in a widely publicized move, federal law enforcement officers from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and other federal agencies deployed to Chicago, focusing on enforcing federal firearms laws. Federal law enforcement efforts against gun crimes can take advantage of tough federal sentencing laws and avoid some of the pretrial release issues that have drawn attention in Chicago.

And perhaps even more important given its vastly larger numbers, the Chicago Police Department created a new “Community Safety Team” that deployed officers to the South and West Sides of Chicago where the spikes in violent crime are occurring. The Community Safety Team is designed to not only supplement existing law enforcement efforts, but also to engage in regular community projects. While it is too early to tell what the effects will ultimately be, the very early results are encouraging. This past weekend in Chicago, the Chicago Police Department recorded 39 shootings. That compared to 41 the previous weekend, 50 the weekend before that, and 87 during the long Fourth of July weekend.

Researchers should continue to investigate why homicides have been spiking in Chicago and other major cities across the country. If the answer is that de-policing is linked to rising gun violence (as some earlier studies would suggest), further limiting police efforts to aggressively deter gun crimes will tragically lead to more shootings and more homicides. And the victims of those crimes will likely come disproportionately from African-American communities—communities that, in some instances, may want more aggressive police efforts to combat gun crimes.

Attorney Barr touched on these de-policing issues in testimony before the House Judiciary Committee yesterday:

When a community turns on and pillories its own police, officers naturally become more risk averse and crime rates soar. Unfortunately, we are seeing that now in many of our major cities. This is a critical problem that exists apart from disagreements on other issues. … And it is not just that crime snuffs out lives. Crime snuffs out opportunity. Children cannot thrive in playgrounds and schools dominated by gangs and drug pushers.

The crime rate patterns discussed above support the Attorney General’s position. These patterns deserve serious scrutiny as the data continue to emerge. The stakes are obviously very high in determining how the nation should respond to this recent spike in gun violence.

Note: I am a member of the CCJ, but was not involved in drafting of the report discussed in this post.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2EwCRTS

via IFTTT