Imagine Ramping Up A “War Time” Economy Where Most Of The Stuff You Shoot At The Enemy, Comes From The Enemy

By Peter Tchir of Academy Securities

If you have not read our 2026 Outlook piece – ProSec 2026, we really urge you to do it. It is our best attempt, to date, to outline why ProSec, or Production for Security (and Resilience) is the dominant theme for this year (and likely for years to come). Not just for the U.S. government (which kicked it off), but also for investors (who are rapidly chasing opportunities in the space), and increasingly for foreign governments and corporations.

We have not “trademarked” the term ProSec (yet), but we have been trying to capture this momentous shift in policy and focus since last summer, and haven’t thought of (or seen) a better way to summarize the New Era.

When we first argued that ProSec is the New ESG – the most common responses were: eye rolls and some reasonably aggressive pushback. That is not the case anymore as the shift in focus and the intensity of that focus is becoming apparent. ProSec has become the core of our discussions. We are learning and refining our take, but the core thesis remains not only intact, but it is also gaining momentum. The FT pointed out that Nuclear Weapons are now ESG Compliant. This is reframing ESG to remain relevant when in reality we are moving to a ProSec World. While the nuclear weapon concept might be a bit over the top, Euronext’s European Defense Bonds smell like capitulation. It will take Europe longer to truly admit that ESG has been replaced, and they are already creating the tools to make it happen, in the guise of the existing framework.

We were inundated (maybe just swamped) with people pointing out the Bipartisan Proposal to create a $2.5 Billion Agency focused on rare earths and critical minerals (someone really needs to simplify rare earths and critical minerals into something catchy and easy). We continue to argue that it is the refining and processing that is most important. More on that in “threats.”

We promise to deliver some semblance of a ProSec equity index this week. That will let people track the performance of ProSec companies. It is likely to evolve (as we get better at this), but it will provide a starting point. While ProSec may seem like an equity story, it will also be a credit story! Some companies will have to issue more debt than planned to achieve their ProSec opportunities (we almost said “goals” but ProSec isn’t about “goals” it is about opportunities). Other companies will see spreads tighten on growth, improved earnings, and possibly, especially for smaller, higher yielding companies, from being acquired. This is about investment to create long-lasting profit opportunities (while achieving security and resilience for your companies, investments, and countries).

If we could just stop the report here, we would. It is important, in our opinion, that if you haven’t read our work on ProSec it isn’t too late, and you should.

But many have read our work and discussed it, so we need to plow on. Also, we can’t ignore last weekend’s Fast and Furious 47, since the admin continued to issue edicts as a “fast and furious” pace.

We are going to go back and forth between deadly serious, and a bit over the top, to try to get our points across (and then we can get back to identifying tickers for our indices).

From ESG to ProSec

Let’s follow a mildly tongue-in-cheek and simplified “decision tree” to where we are in global production. Especially the processing and refining of rare earths and critical minerals. But also, things like steel, copper, solar panels, etc.

You might argue that this is overly simplified. I’d agree. You might argue that this is heavily tongue in cheek. I’d disagree as this is only mildly tongue in cheek.

So here is a take on how we got to where we are.

-

Is the process energy (carbon emission) intensive? Does it produce a lot of pollutants?

-

If so, let’s do that step in [insert country here].

-

-

Did that reduce direct and immediately obvious issues locally?

-

Yes.

-

-

Did it protect the earth against global pollutants, carbon, etc.?

-

Probably not, but “out of sight” = “out of mind.”

-

-

Presumably [insert country here] must have led to a lot of production in different countries?

-

Not really, by and large “insert country here” became China.

-

-

Wow, it must be incredibly difficult to do these things, and that’s why it all went to China?

-

Not really. Most countries create more complex systems and finalize projects all the time. It really just didn’t fit the “framework” that we (the “West”) were looking to develop.

-

Okay, I lied, or at least exaggerated. Initially that was probably correct, but as economies of scale grew and the infrastructure was put in place, there were even greater cost advantages than just not worrying about details like pollution and carbon emissions.

-

-

Ok, so we should be able to bring it back “quickly?”

-

Well, we ceded all of this to China over the course of a decade or two. Sure, we can bring it back more quickly than that, but it will still take time.

-

Before getting to one more “rant” let’s take a look at some real world examples.

The Threat to Our Flow of Semiconductors

Semiconductors have been greatly affected by how the global supply chain shifted. While we all know that Taiwan is the leading semiconductor manufacturer in the world (in terms of state of the art chips), even they are partially dependent on China. The U.S. is even more so, and not so much because of the technology to make chips, but due to what goes into a chip.

Working with ChatGPT for this, we start with the “simple question” of what are the 5 most important materials that go into semiconductor manufacturing and/or the chips themselves? Anything in bold AND italicized was done by Academy to highlight.

Quick hierarchy (mental model)

-

Silicon → physical platform

-

Photoresists → pattern fidelity

-

Copper → performance & power

-

Gases & chemicals → manufacturing viability

-

High-k & specialty metals → advanced scaling

ProSec lens (relevant to your prior themes)

-

Silicon wafers, photoresists, and specialty gases are strategic choke points

-

Rare metals (hafnium, tantalum, cobalt) tie semis directly to mining and refining security

-

Water and electricity intensity makes fabs a critical infrastructure asset

Yes, we have been trying to “train” ChatGPT on our ProSec research.

Sticking with ChatGPT (but eliminating the graphics it provided):

- From silica → electronic-grade silicon (step by step)

1) Raw silica (SiO₂)

-

Comes from quartz / quartzite deposits, abundant globally, but purity and consistency matter

-

Mining alone is not the bottleneck

2) Metallurgical-grade silicon (MG-Si)

Process

- Quartz + carbon (coal/coke/charcoal), smelted in electric arc furnaces at ~2,000°C

Output

- ~98–99% pure silicon, Still far too impure for chips

Where this happens

-

China (dominant), Brazil, Norway, United States (limited, declining)

-

This step is energy-intensive and already geographically concentrated.

-

3) Chemical purification → polysilicon

This is where semiconductor relevance begins.

Process (simplified)

-

MG-Si reacts with HCl → trichlorosilane (SiHCl₃)

-

Distillation removes impurities to parts-per-billion

-

Re-deposition via Siemens process → ultra-pure polysilicon rods

Purity

- Semiconductor grade: 9N–11N (99.9999999%+)

Where this happens (critical chokepoint)

-

China (largest capacity, esp. Xinjiang), Germany, Japan, United States (small but strategic)

-

Only a handful of facilities globally can do true semiconductor-grade purification at scale.

-

4) Single-crystal silicon ingots

Process

-

Melt polysilicon, Grow a single crystal via Czochralski (CZ) or Float-Zone (FZ) methods

-

Slice into 300 mm wafers

Where this happens

-

Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Germany

-

This step is precision engineering, not mining.

Key takeaway (important)

- Silicon is abundant. Semiconductor-grade silicon is not.

The bottleneck is:

- Energy-intensive smelting, Hazardous chemical purification, Extreme quality control, Capital-heavy facilities

Strategic implications (ProSec framing)

-

Mining ≠ security

-

Chemical processing + electricity + know-how = security

Losing access to: Polysilicon purification, Crystal growth, Wafer slicing → fabs go dark, even if chips are designed domestically

- This is why silicon is quietly treated like a strategic material, even though it’s “just sand.”

That was probably more information that you (or I) needed on silicon in chips.

I’m almost embarrassed to have forced you to read it (or skim over it) but chips are mission critical to our (and virtually every) economy.

Also, this was just one of the 5 main “ingredients” in chips.

An “Imaginary” Conversation

With that serious discussion out of the way, we can get a bit more fully “tongue in cheek” and run through a conversation that plays out in my mind over and over (darn, I should have tried to think of a song for today’s T-Report).

-

What would happen if China decided to cut the U.S. off from some of the things we now rely on them for?

-

Why would they do that?

-

-

Ok, but hypothetically, what would happen if China decided to cut the U.S. off from some of the things we now rely on them for?

-

Why would they do that?

-

-

Didn’t we get cut off during COVID?

-

Yes, but that was different because the entire global economy shut down.

-

-

Were the consequences for U.S. manufacturing capacity really bad?

-

Not really because we weren’t making much of anything because people couldn’t go into the office unless they worked in important industries – like finance.

-

-

But it would have hampered us?

-

Sure, but they would never do it on purpose.

-

-

So at least we tried to reduce our exposure against another “accidental” situation, like COVID?

-

There was a lot of chatter about onshoring, re-shoring, friend-shoring, near-shoring, and we even had the CHIPS ACT to boost domestic production of chips.

-

-

So, we aggressively reduced the risk?

-

By “aggressively” (in air quotes) you mean we talked about it a lot? Heck yeah! Actually, accomplished a lot, meh…

-

-

So, we remain vulnerable to China cutting off supplies of various things?

-

Why would they do that?

-

-

But seriously, we remain vulnerable to China?

-

Why would they do that?

-

-

Okay, maybe I should toss out some reasons why they “might” do that:

They think it would create leverage for them to be “handed” Taiwan?

They view us as being in competition to be the major global superpower, and they would employ economic means to achieve their goal.

The race is in chips and AI, where we lead in design and even manufacturing, but remain heavily reliant on Taiwan (in their sphere of

influence) and China for the inputs.

They threatened us repeatedly during trade negotiations, on exactly this topic.

The U.S. now accounts for only 15% of China’s exports and they seem to continue to take steps to reduce the importance of the U.S. economy on their economy, which might lead them to the decision that they can start a real economic war.

They did see how poorly the U.S. responds to inflation and disruption in our “comfortable” lives, so they may be tempted to use that to disrupt us, especially on the race to AI and Space superiority (to name a couple key technologies).

They have been allegedly stockpiling things that are important to them, that they don’t necessarily produce themselves (oil is top of mind, but only one of a number of things).-

Those all sound crazy to me.

-

-

You really think there is no possibility that we experience a disruption, accidentally or on purpose?

-

Well, zero probability might be too low, things do happen.

-

-

Wouldn’t we then be better off if we were prepared for such an eventuality, even if it is a low probability?

-

I guess.

-

Ultimately, the higher the risk you think we face from having supply shortages due to restrictions from China (whether intentional or not) the more urgent and important ProSec is.

In any case, I cannot think of good reasons not to want greater capacity domestically, for security, resilience, and the JOBS created.

In addition, is there a possibility that Venezuela doesn’t so much become a source of rare earths and critical minerals, but instead a major hub for processing rare earths and critical minerals, far more in our “control” than existing sources? It might be a way to outpace regulation in the near-term?

True economic freedom and true sustainability derive from being able to take care of yourself (just ask Maslow).

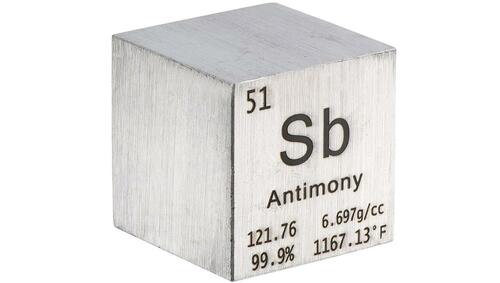

The Threat to the U.S. Military – Antimony

General (ret.) Spider Marks loves bringing up antimony (he has been doing it for years). I’m mildly suspicious he does it primarily because he knows I have trouble pronouncing it, but it is a serious topic. And if it is a threat to our military, imagine the threat it is to other countries’ militaries.

Antimony seems to follow the rather aggressive tone I took in my “make believe” conversation regarding China.

This is more or less an actual conversation with ChatGPT (I have paraphrased its answers because this report is already getting long on technical information, and it is not salient to the point we are trying to make).

-

Is antimony used in munitions?

-

Yes.

-

-

Are there other alternatives?

-

Technically yes, but far less efficient

-

-

Is it the commodity itself or a refined version?

-

No. Munitions use antimony as refined metal or chemical compounds “the refining step is the real choke point.”

-

-

Where does the U.S. get its refined antimony?

-

Over 60% from China.

-

Then directly from ChatGPT (along ProSec lines):

-

What the U.S. does not have:

-

No large-scale primary antimony mine in operation

-

No dedicated munition-grade antimony trisulfide production

-

No surge-capable domestic refining base

-

-

This is the core vulnerability.

Why this is strategically uncomfortable:

- The U.S. can manufacture ammunition domestically, but it depends on foreign chemistry to lighten and harden it.

Imagine ramping up a “war time” economy where most of the stuff you use to shoot at the enemy, comes from the enemy.

It almost hurts to even think about, but that is where we are.

Bottom Line

-

Production.

-

Security.

-

Resiliency.

-

ProSec.

Yes, today’s “Bottom Line” is that simple – ProSec.

Hope you have a great long weekend and I promise we will get back to our rate outlooks, credit outlooks, etc., but we believe that understanding and embracing this topic (as it evolves) will do more for your performance this year, than anything else in your control.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 01/18/2026 – 14:00

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/8GImJr1 Tyler Durden