12/14/1964: Heart of Atlanta Motel v. U.S. and Katzenbach v. McClung are decided.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: December 14, 1964 appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/SUBIkGX

via IFTTT

another site

12/14/1964: Heart of Atlanta Motel v. U.S. and Katzenbach v. McClung are decided.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: December 14, 1964 appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/SUBIkGX

via IFTTT

12/14/1964: Heart of Atlanta Motel v. U.S. and Katzenbach v. McClung are decided.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: December 14, 1964 appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/SUBIkGX

via IFTTT

As the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) transitioned from internet meme to real-life government reform effort, the agency claimed it would achieve many far-reaching, seemingly improbable goals.

It was going to slash $2 trillion in federal spending, eliminate burdensome and unconstitutional regulations, upgrade the federal government’s “tech stack,” evict the woke deep state, and, time permitting, balance the budget.

When it launched, both DOGE supporters and critics seemed to believe the agency was striving for the wholesale dismantling of the federal government. As the dust settles one year later, we can get a more accurate sense of how much DOGE has done to shrink and streamline the federal government.

Its cost-cutting efforts have been unsuccessful, but it did accomplish quite a bit toward shrinking the federal government’s workforce. The Trump administration’s deregulatory drive has been moderately successful, although it’s debatable how much credit DOGE should receive for that.

DOGE’s biggest success on its own terms has been its reduction in federal employees.

When the second Trump administration came into office in January 2024, there were some 2.4 million civilian federal employees. That’s about 1.5 percent of all employed civilian workers.

In its August 2025 jobs report, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) found 97,000 fewer federal workers by the end of that month. That figure does not include the 154,000 workers who accepted DOGE’s “fork in the road” offer to voluntarily leave their federal jobs in exchange for being paid through the end of September 2025.

The precise impact of these deferred resignations on federal employment is difficult to parse, as the October government shutdown has delayed the release of BLS jobs reports that would count the federal workers lost through deferred resignations.

The Partnership for Public Service estimates that as of late September 2025, 201,000 people had left federal employment during the second Trump administration through deferred resignations, early retirements, reductions in force, and the layoffs of probationary employees. This measure isn’t a complete snapshot of the fall in federal employment, as it does not include new hires—like all those extra Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents—or people retiring on schedule.

The Trump administration estimated that number would reach 300,000 by the end of 2025. If that larger figure stands, the Trump administration will have managed to cut the federal workforce by some 12 percent.

A core component of DOGE’s original mission, as outlined in a Wall Street Journal op-ed co-authored by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, was to unilaterally cut federal red tape.

The actual deregulation we’ve seen under the Trump administration has come from more traditional routes: individual agencies issuing deregulatory rules and actions.

Early in his term, the president instructed agencies to impose total regulatory costs that were “significantly less than zero” and to eliminate 10 rules for every one rule adopted. According to a parsing of the latest Unified Agenda by the Economic Policy Innovation Center, the administration is closer to a 5–1 ratio of deregulatory actions to regulatory actions.

It has taken 778 active deregulatory actions, compared to 161 active regulatory actions. Significant deregulatory actions (those with an estimated economic effect of $100 million or more) number 71, compared to 31 significant regulatory actions. That’s less than the Trump administration’s goal, but significantly more deregulation than the Biden administration managed, since it added $1.8 trillion in new regulatory costs.

DOGE’s impact on federal spending is murkier, largely due to its inability to accurately and transparently account for its own claimed savings.

The agency’s website says that it has saved taxpayers $214 billion by canceling contracts, grants, and leases. Unfortunately, DOGE’s “wall of receipts” tallying these savings is riddled with errors and accounting gimmicks.

For instance, the agency will count as a savings the entire value of a contract it canceled, even if much of the obligated money has already been spent.

Another DOGE savings gimmick is to lower the maximum amount the government could potentially spend on a contract, even though those funds had not been spent and likely never would have been spent. This practice, it’s been pointed out, is comparable to taking out a credit card with a $20,000 limit, canceling the card, and then claiming you’ve saved $20,000.

A Politico investigation into DOGE’s claimed savings found that of the $145 billion it claimed to have saved via canceled contracts through the end of June 2025, only $1.4 billion—less than 1 percent—were real, verifiable cash savings.

DOGE did help identify and pause spending that would become the $8.9 billion rescission package passed by Congress in July. For context, that rescission package amounts to less than a percent of the federal discretionary budget. Federal spending in FY 2025 is an ominous $6.66 trillion, compared to $6.29 trillion in FY 2024. The deficit stands at $1.8 trillion.

The post Almost a Year After It Launched, DOGE's Legacy Is Mixed appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/lWEBgms

via IFTTT

As the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) transitioned from internet meme to real-life government reform effort, the agency claimed it would achieve many far-reaching, seemingly improbable goals.

It was going to slash $2 trillion in federal spending, eliminate burdensome and unconstitutional regulations, upgrade the federal government’s “tech stack,” evict the woke deep state, and, time permitting, balance the budget.

When it launched, both DOGE supporters and critics seemed to believe the agency was striving for the wholesale dismantling of the federal government. As the dust settles one year later, we can get a more accurate sense of how much DOGE has done to shrink and streamline the federal government.

Its cost-cutting efforts have been unsuccessful, but it did accomplish quite a bit toward shrinking the federal government’s workforce. The Trump administration’s deregulatory drive has been moderately successful, although it’s debatable how much credit DOGE should receive for that.

DOGE’s biggest success on its own terms has been its reduction in federal employees.

When the second Trump administration came into office in January 2024, there were some 2.4 million civilian federal employees. That’s about 1.5 percent of all employed civilian workers.

In its August 2025 jobs report, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) found 97,000 fewer federal workers by the end of that month. That figure does not include the 154,000 workers who accepted DOGE’s “fork in the road” offer to voluntarily leave their federal jobs in exchange for being paid through the end of September 2025.

The precise impact of these deferred resignations on federal employment is difficult to parse, as the October government shutdown has delayed the release of BLS jobs reports that would count the federal workers lost through deferred resignations.

The Partnership for Public Service estimates that as of late September 2025, 201,000 people had left federal employment during the second Trump administration through deferred resignations, early retirements, reductions in force, and the layoffs of probationary employees. This measure isn’t a complete snapshot of the fall in federal employment, as it does not include new hires—like all those extra Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents—or people retiring on schedule.

The Trump administration estimated that number would reach 300,000 by the end of 2025. If that larger figure stands, the Trump administration will have managed to cut the federal workforce by some 12 percent.

A core component of DOGE’s original mission, as outlined in a Wall Street Journal op-ed co-authored by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, was to unilaterally cut federal red tape.

The actual deregulation we’ve seen under the Trump administration has come from more traditional routes: individual agencies issuing deregulatory rules and actions.

Early in his term, the president instructed agencies to impose total regulatory costs that were “significantly less than zero” and to eliminate 10 rules for every one rule adopted. According to a parsing of the latest Unified Agenda by the Economic Policy Innovation Center, the administration is closer to a 5–1 ratio of deregulatory actions to regulatory actions.

It has taken 778 active deregulatory actions, compared to 161 active regulatory actions. Significant deregulatory actions (those with an estimated economic effect of $100 million or more) number 71, compared to 31 significant regulatory actions. That’s less than the Trump administration’s goal, but significantly more deregulation than the Biden administration managed, since it added $1.8 trillion in new regulatory costs.

DOGE’s impact on federal spending is murkier, largely due to its inability to accurately and transparently account for its own claimed savings.

The agency’s website says that it has saved taxpayers $214 billion by canceling contracts, grants, and leases. Unfortunately, DOGE’s “wall of receipts” tallying these savings is riddled with errors and accounting gimmicks.

For instance, the agency will count as a savings the entire value of a contract it canceled, even if much of the obligated money has already been spent.

Another DOGE savings gimmick is to lower the maximum amount the government could potentially spend on a contract, even though those funds had not been spent and likely never would have been spent. This practice, it’s been pointed out, is comparable to taking out a credit card with a $20,000 limit, canceling the card, and then claiming you’ve saved $20,000.

A Politico investigation into DOGE’s claimed savings found that of the $145 billion it claimed to have saved via canceled contracts through the end of June 2025, only $1.4 billion—less than 1 percent—were real, verifiable cash savings.

DOGE did help identify and pause spending that would become the $8.9 billion rescission package passed by Congress in July. For context, that rescission package amounts to less than a percent of the federal discretionary budget. Federal spending in FY 2025 is an ominous $6.66 trillion, compared to $6.29 trillion in FY 2024. The deficit stands at $1.8 trillion.

The post Almost a Year After It Launched, DOGE's Legacy Is Mixed appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/lWEBgms

via IFTTT

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/rSq4oum

via IFTTT

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/rSq4oum

via IFTTT

During the first week of December, I spent several days doing speaking engagements in Mexico. Although I have previously visited several Latin American nations, and even twice served as a visiting professor in Argentina, this was my first-ever visit to our southern neighbor. I spoke on a panel on “Migration in the 21st Century” at the FIL Guadalajara International Book Fair (one of the largest book fairs in the Spanish-speaking world), and gave two talks on democracy and political ignorance at the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (Tec de Monterrey), one of the country’s leading universities. The experience gave me some interesting new perspective on our vitally important neighbor to the south.

Before continuing, I should emphasize I am not an expert on Mexico, and I speak little Spanish (though my wife, who came with me on the trip, is fluent in the language). In addition, I obviously did not encounter anything like a statistically representative sample of Mexicans. This post, therefore, can provide only very modest insight. But that modest insight might still have some value.

At least when it comes to Guadalajara and Monterrey, Mexico seems a much more affluent nation than many Americans might assume. My family and I saw little, if any of the grinding poverty that is commonplace in many poor countries I have been to, such as China, Russia, El Salvador, and Uruguay. For example, we saw almost no homeless people or beggars.

Guadalajara and Monterrey are two of Mexico’s wealthiest cities; thus not representative. But, in many poor countries, poverty is evident in relatively affluent areas. Mexico’s economic progress is also evident from per capita GDP statistics, which show rapid gains in recent years. The country is no longer the cesspool of poverty some in the US imagine it to be.

This progress was, also, in some ways, in evidence at the FIL Guadaljara book fair, when I spoke there. Not surprisingly, the other panelists and most audience members were sympathetic to my pro-immigration and anti-restrictionist perspective. But one of the panelists – prominent Mexican political consultant and former diplomat Gabriel Guerra – noted that Mexico itself has been facing an influx of migrants in recent years, and the government’s treatment of them has sometimes been unjust and indefensible. Mexico has gone from being the biggest source of migrants to the US, to itself being a magnet for migrants from Central America and Venezuela. The Mexican government’s flawed policies do not justify those of the US (and vice versa). But these issues do throw a wrench in the traditional view of the US-Mexican relationship, when it comes to migration. The changing migration patterns, obviously, reflect Mexico’s increasing relative affluence.

Not all is rosy in Mexico, by any means. Mexican academics and policy experts I spoke to are deeply concerned about the state of the US-Mexican relationship, given Donald Trump’s unleashing of massive new tariffs, and harsh immigration policies. After the Guadalajara panel, I spoke at length with Guerra and others, including Arturo Sarukhan, former Mexican ambassador to the US. They noted that Trump’s policies have not yet generated a “nationalist backlash” in Mexico (their term, not mine), but that such a backlash was likely to develop. They noted that many Mexicans have friends and relatives among Mexican immigrants in the US, who are feeling the effects of the new administration’s policies of racial profiling and expanded detention and deportation. That, along with the trade war, is bound to cause anger and poison relations between the two countries.

I pointed out that Trump will not be in power forever (or perhaps even for very long), and a future administration might well revoke his policies. My Mexican interlocutors were not mollified. They emphasized that much damage has already been done to the US-Mexican relationship, and that it will be difficult to reverse.

I do not know to what extent they are right about this. But, regardless, alienating our most populous neighbor and biggest trading partner isn’t Making American Great Again. Exactly the opposite, in fact. The more we damage relationships with neighbors and allies, the harder it will be to counter adversaries like Russia and China.

The general sense of progress and rising affluence was also partly offset by the – in Guadalajara – ubiquitous posters depicting “desaparecidos” – “disappeared” people believed to have been abducted by drug cartels (or, in some cases, to have joined them voluntarily).

Sadly, the cartels are indeed a significant presence in Mexican society, even in relatively affluent cities. One prominent Mexican academic recounted a story of how he had been “mugged” by cartel operatives who searched him “like professional security guards.” He was, he said, relieved they “only” took his smartphone, and nothing else.

These revelations do not shake my opposition to the War on Drugs. In both Mexico and elsewhere, criminal cartels have the power they do because prohibitionist policies have created a vast black market for them to exploit. Legalization would undermine the cartels, and eliminate most of the violence associated with their operations, just as the end of Prohibition largely eliminated the role of organized crime in the sale of alcoholic beverages. But, whatever policy lessons, the impact of the drug cartels on Mexican society is a significant one.

After Guadalajara, we went to Monterrey, where I gave two talks at the Tec de Monterrey, and also met with law and social science students and faculty. These events were organized by my graduate school classmate Gabriel Aguilera, who is now the Dean of the School of Social Sciences and Government there.

I offered a range of different lecture topics within my areas of expertise, such as issues related to migration rights, federalism, property rights, constitutional theory, and more. But Gabriel and his colleagues chose to have me do both talks on issues related to political ignorance. In recent years, I see growing interest in this topic around the world. One might say it has been “made great again.” But, in truth, it goes beyond any one one nation or political movement, and has long been a major challenge for democracy.

When I first started writing about political ignorance over 25 years ago, many scholars and others argued that voter knowledge levels are not a significant problem, because voters who know very little about government and public policy can still do a good job thanks to information shortcuts, the “miracle of aggregation,” and other workarounds.

Such optimism is far less prevalent today. In Mexico, as in recent talks I have given about political ignorance elsewhere, virtually all the questioners presumed that voter ignorance is indeed a serious problem, though some took issue with my proposals for mitigating it. Voter ignorance is, in fact, a serious problem in democracies around the world. But at least there is growing cross-national recognition of its significance. In Mexico, concerns about this topic have recently been heightened by the government’s erosion of judicial independence, which has weakened a significant check on demagogic populist leaders and political majorities.

My time at Tec de Monterrey also gave me some new perspective on Mexican academia. A number of the law and social science faculty I met are not from Mexico or elsewhere in Latin America, but from countries around the world, including some from east Asian nations, such as China and South Korea. I asked Gabriel if these non-Hispanic academics already spoke Spanish before being hired, or were required to learn after taking up their positions. He noted that many of them actually teach and write in English, which is the language in which many social science courses at Tec are taught. If this is any indication, Mexican academia is becoming more cosmopolitan, and is a competitor for hiring talent from around the world. Gabriel himself came to the US as a poor immigrant, held a number of academic positions at American universities, and returned to Mexico to take his current high-level post.

On a less academic/intellectual note, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a university anywhere in the world that has as many peacocks and deer on campus as Tec does:

![]()

The post Reflections on Lecturing in Mexico appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/fktiXan

via IFTTT

During the first week of December, I spent several days doing speaking engagements in Mexico. Although I have previously visited several Latin American nations, and even twice served as a visiting professor in Argentina, this was my first-ever visit to our southern neighbor. I spoke on a panel on “Migration in the 21st Century” at the FIL Guadalajara International Book Fair (one of the largest book fairs in the Spanish-speaking world), and gave two talks on democracy and political ignorance at the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (Tec de Monterrey), one of the country’s leading universities. The experience gave me some interesting new perspective on our vitally important neighbor to the south.

Before continuing, I should emphasize I am not an expert on Mexico, and I speak little Spanish (though my wife, who came with me on the trip, is fluent in the language). In addition, I obviously did not encounter anything like a statistically representative sample of Mexicans. This post, therefore, can provide only very modest insight. But that modest insight might still have some value.

At least when it comes to Guadalajara and Monterrey, Mexico seems a much more affluent nation than many Americans might assume. My family and I saw little, if any of the grinding poverty that is commonplace in many poor countries I have been to, such as China, Russia, El Salvador, and Uruguay. For example, we saw almost no homeless people or beggars.

Guadalajara and Monterrey are two of Mexico’s wealthiest cities; thus not representative. But, in many poor countries, poverty is evident in relatively affluent areas. Mexico’s economic progress is also evident from per capita GDP statistics, which show rapid gains in recent years. The country is no longer the cesspool of poverty some in the US imagine it to be.

This progress was, also, in some ways, in evidence at the FIL Guadaljara book fair, when I spoke there. Not surprisingly, the other panelists and most audience members were sympathetic to my pro-immigration and anti-restrictionist perspective. But one of the panelists – prominent Mexican political consultant and former diplomat Gabriel Guerra – noted that Mexico itself has been facing an influx of migrants in recent years, and the government’s treatment of them has sometimes been unjust and indefensible. Mexico has gone from being the biggest source of migrants to the US, to itself being a magnet for migrants from Central America and Venezuela. The Mexican government’s flawed policies do not justify those of the US (and vice versa). But these issues do throw a wrench in the traditional view of the US-Mexican relationship, when it comes to migration. The changing migration patterns, obviously, reflect Mexico’s increasing relative affluence.

Not all is rosy in Mexico, by any means. Mexican academics and policy experts I spoke to are deeply concerned about the state of the US-Mexican relationship, given Donald Trump’s unleashing of massive new tariffs, and harsh immigration policies. After the Guadalajara panel, I spoke at length with Guerra and others, including Arturo Sarukhan, former Mexican ambassador to the US. They noted that Trump’s policies have not yet generated a “nationalist backlash” in Mexico (their term, not mine), but that such a backlash was likely to develop. They noted that many Mexicans have friends and relatives among Mexican immigrants in the US, who are feeling the effects of the new administration’s policies of racial profiling and expanded detention and deportation. That, along with the trade war, is bound to cause anger and poison relations between the two countries.

I pointed out that Trump will not be in power forever (or perhaps even for very long), and a future administration might well revoke his policies. My Mexican interlocutors were not mollified. They emphasized that much damage has already been done to the US-Mexican relationship, and that it will be difficult to reverse.

I do not know to what extent they are right about this. But, regardless, alienating our most populous neighbor and biggest trading partner isn’t Making American Great Again. Exactly the opposite, in fact. The more we damage relationships with neighbors and allies, the harder it will be to counter adversaries like Russia and China.

The general sense of progress and rising affluence was also partly offset by the – in Guadalajara – ubiquitous posters depicting “desaparecidos” – “disappeared” people believed to have been abducted by drug cartels (or, in some cases, to have joined them voluntarily).

Sadly, the cartels are indeed a significant presence in Mexican society, even in relatively affluent cities. One prominent Mexican academic recounted a story of how he had been “mugged” by cartel operatives who searched him “like professional security guards.” He was, he said, relieved they “only” took his smartphone, and nothing else.

These revelations do not shake my opposition to the War on Drugs. In both Mexico and elsewhere, criminal cartels have the power they do because prohibitionist policies have created a vast black market for them to exploit. Legalization would undermine the cartels, and eliminate most of the violence associated with their operations, just as the end of Prohibition largely eliminated the role of organized crime in the sale of alcoholic beverages. But, whatever policy lessons, the impact of the drug cartels on Mexican society is a significant one.

After Guadalajara, we went to Monterrey, where I gave two talks at the Tec de Monterrey, and also met with law and social science students and faculty. These events were organized by my graduate school classmate Gabriel Aguilera, who is now the Dean of the School of Social Sciences and Government there.

I offered a range of different lecture topics within my areas of expertise, such as issues related to migration rights, federalism, property rights, constitutional theory, and more. But Gabriel and his colleagues chose to have me do both talks on issues related to political ignorance. In recent years, I see growing interest in this topic around the world. One might say it has been “made great again.” But, in truth, it goes beyond any one one nation or political movement, and has long been a major challenge for democracy.

When I first started writing about political ignorance over 25 years ago, many scholars and others argued that voter knowledge levels are not a significant problem, because voters who know very little about government and public policy can still do a good job thanks to information shortcuts, the “miracle of aggregation,” and other workarounds.

Such optimism is far less prevalent today. In Mexico, as in recent talks I have given about political ignorance elsewhere, virtually all the questioners presumed that voter ignorance is indeed a serious problem, though some took issue with my proposals for mitigating it. Voter ignorance is, in fact, a serious problem in democracies around the world. But at least there is growing cross-national recognition of its significance.

My time at Tec de Monterrey also gave me some new perspective on Mexican academia. A number of the law and social science faculty I met are not from Mexico or elsewhere in Latin America, but from countries around the world, including some from east Asian nations, such as China and South Korea. I asked Gabriel if these non-Hispanic academics already spoke Spanish before being hired, or were required to learn after taking up their positions. He noted that many of them actually teach and write in English, which is the language in which many social science courses at Tec are taught. If this is any indication, Mexican academia is becoming more cosmopolitan, and is a competitor for hiring talent from around the world. Gabriel himself came to the US as a poor immigrant, held a number of academic positions at American universities, and returned to Mexico to take his current high-level post.

On a less academic/intellectual note, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a university anywhere in the world that has as many peacocks and deer on campus as Tec does:

![]()

The post Reflections on Lecturing in Mexico appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/fktiXan

via IFTTT

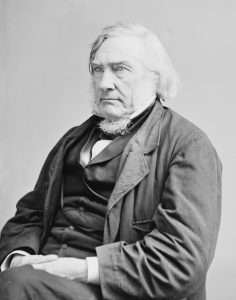

12/13/1873: Justice Samuel Nelson died.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: December 13, 1873 appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/vL3bmkw

via IFTTT

America is lonelier than ever. Recent surveys find that nearly half of Americans report feeling lonely, and 21 percent express experiencing “serious loneliness.” Close friendships are also in free fall across the country. In 2021, the American Enterprise Institute’s Survey Center on American Life found that close friendships have “declined considerably over the past several decades,” with 12 percent of Americans reporting “they did not have any close friends.”

Documented causes of this loneliness epidemic include social media and the rise in remote work, mental health challenges, and the decline of what sociologist Ray Oldenburg famously called “third places“—the spaces beyond home and work where people meet and connect.

Historically, churches, fraternal organizations, and even bowling leagues functioned as third places where people found connection. Such institutions are now in steady decline, but the demand for connection is not. Now, Americans are turning to recreational amenities such as pickleball courts and dog parks to fill the void that traditional institutions once met.

But the supply of these new third places has failed to keep pace. As our lonely society searches for connection, America desperately needs more of these spaces, and at sufficient quality to attract and sustain demand. One tool long championed by libertarians could help close this gap: user fees.

Consider pickleball, which has been America’s fastest-growing sport for four consecutive years. Nearly 20 million Americans played the paddle sport in 2024, a 311 percent increase since 2021. Its distinctive “open play” format brings strangers together on public courts, fostering the kind of social interaction needed to combat loneliness. As writer and pickleball player Mitch Dunn says, the pickleball court is “a Third Place where we meet new people, collaborate with them, and leave wanting to do it all over again as soon as possible.”

But even pickleball courts are in short supply. Despite adding 18,000 new courts in 2024, major metropolitan areas remain underserved. New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago all sit roughly 90 percent below national averages for dedicated court density, according to data from the Sports and Fitness Industry Association. The result is overcrowded facilities and frustrated players—hardly a recipe for fostering the relaxed social atmosphere that makes third places work.

User fees offer municipalities a way to expand these amenities without further straining the public fisc. Earlier this year, Burlington, North Carolina, opened a pickleball complex featuring 17 courts. The complex is operated by the city using a blended funding system of member and non-member user fees. For a $20 monthly fee, members get advanced court reservations and free use of the ball machine, while non-members can access the courts for a $3 entry fee. Other cities are implementing similar systems.

The possibilities extend far beyond pickleball. Dog parks have come to play a similar community-building role. In an analysis of Dallas-area parks, researcher Lori Lee concluded that dog parks qualify as third places that “encourage people to discard passive imitations of life to take part actively.” Whereas alcohol historically acted as a social lubricant in many third places, such as the local tavern, Lee argues that dogs increasingly act as a new type of social stimulant by encouraging humans to talk to each other and swap pet stories. Unfortunately, dog parks face their own funding shortfalls across the country.

Public swimming pools offer another example, but more and more are closing as local governments face chronically underfunded parks and recreation budgets. The same is true for trails and other outdoor amenities, which are increasingly operating as third places.

The economic logic of user fees is straightforward: Fees are incurred by those who directly benefit from the service, rather than taxing the general population. And when revenues are retained and reinvested in those services, it creates a virtuous cycle—more users means more funding for improvements, which attracts still more users. Reason Foundation and other free market organizations, such as the Property and Environment Research Center, have long championed such user-pays-user-benefits models. This concept could easily extend to municipal park systems to fund the amenities most desired by the local community.

Of course, markets are already responding to America’s demand for social recreational spaces. Private pickleball clubs are proliferating, as are mountain biking trails and hiking destinations on privately owned lands. But voters still expect many recreational opportunities to be provided publicly. Even within this constraint, user fees offer a productive path forward.

The approach addresses multiple policy goals simultaneously. User-fee models could help reduce property taxes by shifting recreational costs from general revenues to direct beneficiaries. They also create sustainable funding streams that are less susceptible to politically motivated appropriations. They generate resources not only to build more parks, trails, and recreation facilities, but also to improve their quality so they attract more Americans seeking to escape their screens and rediscover community.

Embracing user fees could increase the supply of third places without tax hikes or unnecessary growth in government coffers. In turn, Americans could gain access to forums in which they can get off their smartphones, connect with other human beings, and maybe even make a friend or two along the way.

The post Americans Need More and Better 'Third Places.' User Fees Can Help. appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/ocxNPqM

via IFTTT