In what is likely going to prove to be a fascinating, if not all-out frightening experiment, New York City is about to find out what happens when its vital L train shuts down. Starting Friday night, the tunnel that ties Brooklyn and Manhattan together on the line is partially shutting down on nights and weekends for repairs, according to Bloomberg. Riders are anxious about what this will do to the already dilapidated and crowded subway system. And the true test will come during Monday morning’s commute, when the tunnel is supposed to re-open.

Rebecca Pappa, an art therapist who lives in Bushwick, Brooklyn said: “For me, it’s going to be a pain. I still don’t know exactly what’s happening. There’s been a lot of different information out there.”

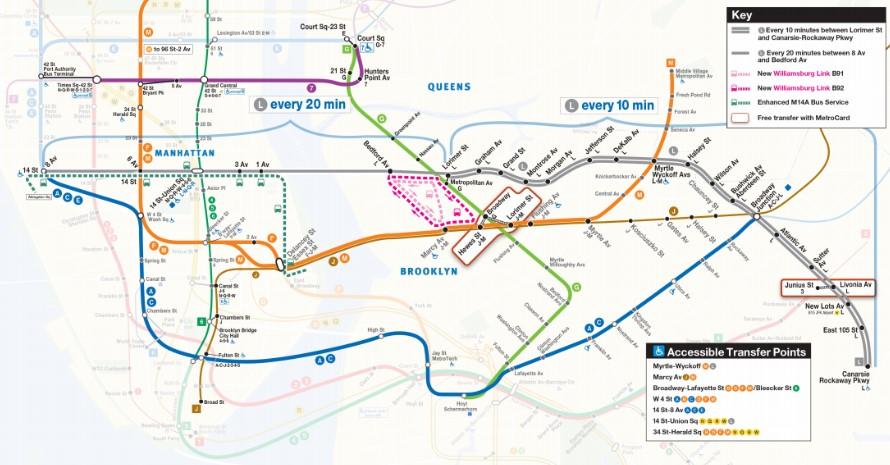

In January, Governor Andrew Cuomo called off a full shut down of the tunnel for 15 months and instead offered a new approach that would close one tunnel at a time and limit the closures to just nights and weekends.

The new plan is called the “L train slowdown” and was cheered by riders who will keep their line to Manhattan. At the same time, it raises questions over safety and whether or not riders are going to have alternatives on nights and weekends when transit officials have already warned that crowding may make it so bad that stations could close temporarily.

This leads to the obvious question: then what’s the point of keeping them open?

The repairs are going to be a major challenge for the MTA which is constantly under fire for slow work and going over budget. It’s also a test for Governor Cuomo, who essentially took on responsibility for the entire project.

While planning for the project, officials had concerns that removing concrete would create silica dust, a toxic mineral that can cause lung cancer. The MTA has said – surprise – they’re confident that the dust will not pose a risk.

But this doesn’t mean that some riders aren’t doubtful. Michael Magner, an L train rider who lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, said he was concerned about the dust, especially since there was no independent review of the construction approach. He said: “I don’t know enough about exactly how dangerous silica dust is compared to something like asbestos. It seems bad, but not as bad as that.”

The authority’s chief development officer, Janno Lieber, responded: “This is not new stuff — we deal with concrete and its demolition every day, and have well established methods in place to handle this work safely. We have adopted a hyper-conservative standard, and have every precaution in place to protect workers and the public.”

His agency said it will post the silica dust levels online once a week to keep the public informed.

This didn’t stop transit workers from holding a protest at the Bedford Avenue station in Brooklyn earlier this month. The MTA’s managing director, Veronique Hakim, called the protests “irresponsible”, saying “It’s ludicrous to think that we would do anything to put our employees or our customers at risk.”

In typical New York fashion, other riders are concerned less about inhaling toxic dust that might kill them and more about getting where they’re going.

Amy Lucker, a librarian at New York University said: “It’s going to be a pain in the butt anytime I want to leave my neighborhood

on the weekend. Anybody who thinks it’s not going to spill over to the weekdays is deluding themselves. It’s going to be general annoyance for at least a year and a half.”

The MTA’s Twitter account said this week that “stations will be way more crowded than usual”.

Mitchell L. Moss, the director of the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University said that car sharing and ride sharing services will be the beneficiary: “The real winners are Uber Pool and Shared Lyft. That’s how

people are going to come and go to bars and restaurants.”

But still, ride sharing isn’t a realistic solution for many New Yorkers. Sam Kerins, an actor who lives in Brooklyn, said simply: “I can’t afford to Uber everywhere.”

Stephanie Rosario, a hearing screener for newborns who lives in Ridgewood, Queens, thinks the plan is too little, too late from Cuomo: “I honestly think they should have shut the whole thing down. If you want to build something and to fix it, then fix it well.”

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2GQl60F Tyler Durden