At the end of May, the world’s largest bond manager, Pimco, whose bread and butter depends entirely on the future of the price of bonds and by implication, interest rates (and being able to correctly predict where they go) and thus, on the Fed’s continued control of the market, made an ominous warning. Speaking to Bloomberg TV, the CIO of core strategies at PIMCO, Scott Mather, said that “we have probably the riskiest credit market that we have ever had” in terms of size, duration, quality and lack of liquidity” adding that the current situation compares to mid-2000s, just before the global financial crisis.

“We see it in the build up in corporate leverage, the decline in credit quality, and declining underwriting standards – all this late-cycle credit behavior we began to see in 2005 and 2006.”

What was even more concerning was Mather’s warning that the era where central banks are “powerful in terms of taking volatility out of the market and pumping asset prices up” is coming to an end: “The U.S. is about the only central bank that was able to normalize policy rates, but elsewhere, there is basically no monetary firepower left… I think that’s what you’re seeing now in markets. People are starting to come to a more realistic outlook about the forward-looking growth prospects, as well as the power of central banks to pump up asset prices.”

In short, and just like the BIS cautioned about a month later, central bank intervention in markets – the primary driver behind record high stock prices, and most if not all of the S&P’s upside in 2019 – is coming to an end, as the ability of central banks to actively manage markets is ending (watch the full interview here).

Today, following in the footsteps of the world’s biggest bond manager, is the head of the world’s biggest hedge fund, Ray Dalio, whose Bridgewater manages over $150 billion in AUM, and who voiced the same concern, if even more forecefully.

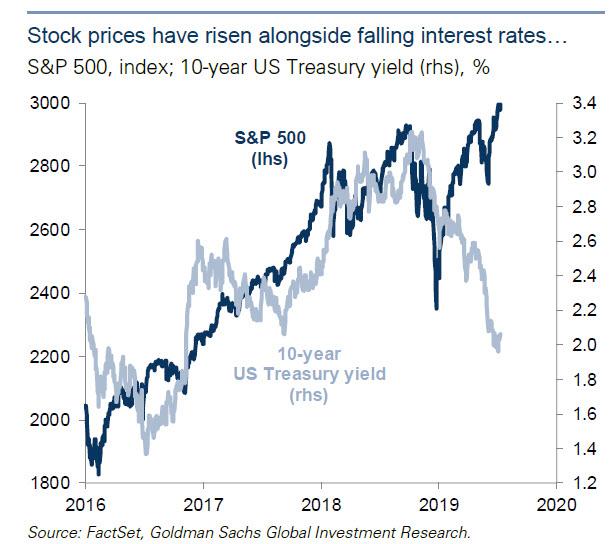

Speaking to Goldman’s Allison Nathan, author of the popular Top of Mind publication, Dalio echoed Pimco’s Mather, saying that “when the Fed shifted to a much easier stance, it made sense that both interest rates fell—which was good for bonds—and stock prices rose. But the power to do this is limited. Think of central banks cutting interest rates and purchasing financial assets (QE) as shooting doses of stimulants into their economies and markets.”

Then, repeating what we have cautioned for the past 10 years, Dalio said that “the financial world is now awash with liquidity chasing investments because of all the rate cuts and especially the QE that put $15trn into the hands of investors since the Global Financial Crisis. The Fed and other central banks easing today will push more money and credit into financial assets, which will cause prices to rise but future expected returns to decline. In other words, it’s short-term bullish and long-term bearish because future expected returns will fall and central banks are running out of stimulants; interest rates are already very close to zero, and the Fed pushing more money into the system by printing it and buying financial assets will soon push the expected returns for equities and other assets as low as they can go.”

Naturally, “once we get to the point that stimulating via rate cuts and QE isn’t sufficient to offset market and economic weakness, market action will change,” which then prompted the obvious follow up question: “how close do you think we are to that” moment?

Dalio’s answer was troubling not only for all market bulls, but also for president Trump who is hoping to ride the record highs in the S&P500 into the 2020 presidential election, to wit: “Pretty close. There is now only a limited amount of stimulant left in the bottle, and the sooner we use it, the sooner it will run out. I’d say that there is about a one-to-three year supply left.”

The Fed only has room to cut about 2%, which isn’t much because past recessions needed about 5% of cuts. These cuts, together with QE, might be enough to prevent a recession for a few more years. But interest rates in Europe and Japan have no significant room to decline at the same time that printing money and buying financial assets will have very limited effects. So we’ll see “pushing on a string” in that part of the world.

“All told”, Dalio predcits that “monetary policies will be dangerously low on power in a couple of years when the next downturn is more likely to come.” It’s worse than that, because if the market recognizes that the Fed and/or all other central banks can no longer levitate markets, and considering that the S&P is about a few hundred percent higher than where it would be without central banks “pumping up prices”, the market is about to go through a lot of pain in the near future if the world’s largest bond manager and the founder of the world’s largest hedge fund are correct.

* * *

Dalio’s full interview below, courtesy of Goldman’s Allison Nathan and “Top of Mind”:

Ray Dalio is the Founder, Chairman, and Co-Chief Investment Officer of Bridgewater Associates. Below he argues that a risky environment for the economy and markets lies ahead, and shares his views on how to best position for it.

Allison Nathan: Equities and Treasuries have both rallied sharply. Is there a disconnect between the pricing of stocks and bonds today?

Ray Dalio: I don’t see an inconsistency in the recent performance of stocks and bonds because stock values are fundamentally determined by the present value of expected cash flows. So, when the Fed shifted to a much easier stance, it made sense that both interest rates fell—which was good for bonds—and stock prices rose.

But the power to do this is limited. Think of central banks cutting interest rates and purchasing financial assets— Quantitative Easing (QE)—as shooting doses of stimulants into their economies and markets. The financial world is now awash with liquidity chasing investments because of all the rate cuts and especially the QE that put $15trn into the hands of investors since the Global Financial Crisis. The Fed and other central banks easing today will push more money and credit into financial assets, which will cause prices to rise but future expected returns to decline. In other words, it’s short-term bullish and long-term bearish because future expected returns will fall and central banks are running out of stimulants; interest rates are already very close to zero, and the Fed pushing more money into the system by printing it and buying financial assets will soon push the expected returns for equities and other assets as low as they can go. When we get to the point that stimulating via rate cuts and QE isn’t sufficient to offset market and economic weakness, market action will change.

Allison Nathan: How close do you think we are to that?

Ray Dalio: Pretty close. There is now only a limited amount of stimulant left in the bottle, and the sooner we use it, the sooner it will run out. I’d say that there is about a one-to-three year supply left, depending mostly on domestic and international political outcomes and the policies that result from them. The Fed only has room to cut about 2%, which isn’t much because past recessions needed about 5% of cuts. These cuts, together with QE, might be enough to prevent a recession for a few more years. But interest rates in Europe and Japan have no significant room to decline at the same time that printing money and buying financial assets will have very limited effects. So we’ll see “pushing on a string” in that part of the world. All told, I think monetary policies will be dangerously low on power in a couple of years when the next downturn is more likely to come.

Allison Nathan: Given your concerns about monetary policy limitations, do you agree with the increasingly dovish stance of the Fed—not to mention the ECB—or is it setting itself up for a policy mistake?

Ray Dalio: I think that the Fed’s dovish shift was appropriate and that it’s admirable that the Fed recognized its mistake in over-tightening monetary policy last year, which occurred because the Fed misgauged inflation and growth risks, as well as the asymmetry around those risks. Fed officials were too worried about the combination of fiscal stimulus from the 2017 tax cuts and low unemployment, figuring they would accelerate inflation, so the brakes needed to be put on. They didn’t understand the powers of technological improvements on inflation, and they focused too much on the short-term spurt in growth, so markets plunged at the end of the year. Their response to that sharp fall and their sound reflections about why they were wrong about inflation and growth led to the Fed’s smart and significant change in monetary policy.

Allison Nathan: So you don’t agree with the narrative that bond market pricing in and of itself is having an undue influence on the Fed’s decision-making?

Ray Dalio: I don’t. People who make that argument presume that the Fed thinks the bond market is right, so if yields are declining or the yield curve inverts, the bond market must be seeing something that the Fed should pay attention to, and should proceed more cautiously. While this is reasonable to some extent, the bigger question is whether something fundamental is causing long rates to decline. In my view, several factors warranted lower long rates. Most obvious is slowing growth around the world, which suggests a need for easier monetary policy. Additionally, with US interest rates high in relation to those in the two other reserve currencies—the Euro and the Yen—at the same time that the US dollar has been appreciating, it’s reasonable that US interest rates would fall at a faster pace than the Fed is easing.

Allison Nathan: What’s driving your pessimistic outlook on global growth?

Ray Dalio: I’m focused on four factors.

- First, we’re well along in what I call the short-term debt cycle, which is also called the business cycle. We don’t see the same rates of debt growth and spending growth as we’ve seen in the past because balance sheets won’t sustain that, so we will see a slowing. At the same time, pension and healthcare liabilities will increasingly be coming due, which will intensify the squeeze in the same sort of way that debts coming due does.

- Second, we’re also late in the long-term debt cycle, which is what we discussed before about central banks running out of stimulants left in the bottle.

- The third factor is political polarity in an election year, which will largely be a clash between socialism and capitalism. This clash is classically due to today’s substantial wealth, income, and opportunity gaps, which most likely will either lead to big changes in policies that aren’t good for the capital markets and the capitalists—such as a rolling back of the corporate tax rate cut and raising other taxes—or it won’t lead to such changes, in which case the clash between the rich capitalists and the poor socialists in the next downturn will be ugly.

- The fourth factor is increasing geopolitical risk, especially as China continues to emerge and challenge US leadership in many areas. This period is most analogous to the late 1930s, when we were also at the end of short- and long-term debt cycles, so monetary policy was limited, the wealth gap was similarly wide, populism was on the rise, and the existing world powers of the UK and the US were being challenged by the emerging powers of Germany and Japan. Each of those factors—the downward pressures coming from the maturing IOUs, central banks not having much power to stimulate, the large wealth and political gaps within countries, and the challenging of leading world powers by strong emerging world powers—leads to difficult consequences.

Allison Nathan: What will all of this mean for markets?

Ray Dalio: This confluence of factors will create a risky environment over the next couple of years. This is especially true because a number of influences that produced the ups in markets and economies will be fading or reversing. For example, companies bought back shares and pursued mergers and acquisitions because the equity price rises lowered the return spread; so it’s not as good as it was. The corporate tax cut boosted valuations, but there will not be another one of those and there is a decent possibility that it will be reversed. The big rise in profit margins over the last two decades from about 7% of revenue to about 15% today, which also shifted wealth from workers to the capital markets and capitalists, is unlikely to continue. And, as we discussed, monetary policy will have less power to stimulate. All of this will be happening when substantial unfunded liabilities in the form of public pension funds and healthcare liabilities will be coming due, which can only be met with higher taxes and/or the monetization of fiscal deficits. So, looking forward, I see a number of factors that have been supportive of markets no longer existing, and an environment of greater risk.

Allison Nathan: Do you think these risks will culminate in a US or possibly global recession in the next few years? And how severe of a downturn is it shaping up to be?

Ray Dalio: I think there will be slow growth rather than a meaningful recession in the near term. When exactly the next recession will occur is difficult to say; I can’t tell you whether it’ll be in the next one, two, or three years. I can say that by most measures this cyclical expansion is old and we are currently seeing global weakening.

But when the downturn comes, there is little doubt that it will exacerbate these internal and external conflicts; if they seem difficult now when times are good, imagine what they’ll seem like when times are bad. That said, I don’t think the next downturn will be as severe as the 2008 financial crisis. We anticipated that crisis by calculating the debts coming due, and determining that we were headed for a classic debt crisis. Next time around, I think the downturn will be like a big squeeze in a politically challenging environment, much more akin to what we saw in the late 1930s. But that makes it very risky in its own way, leaving us more susceptible to political risk, currency devaluations, and so forth.

Allison Nathan: So is now the time to start reducing risk? How should investors be positioning today?

Ray Dalio: The question really is how does one reduce risk? People seem to think that going to cash reduces risk. But that’s only the case from a standard deviation perspective. When interest rates are negligible—below the inflation rate/nominal GDP growth—and you pay taxes on that, you’re not getting any return. Cash over the long run is the worst performing asset class and therefore the riskiest asset class. So where do you go? To me, going to any one asset increases risk. So the best way to deal with the challenging environment I foresee is by diversifying well.

I think investors today are mostly leveraged long, meaning they own risky assets and have substantially leveraged those assets through company buybacks, private equity, and so on. In order to diversify against this—i.e. reduce exposure to leveraged long portfolios—investors should look to other stores of wealth and areas that have intrinsic diversification. For example, I think gold and Chinese assets are two assets that are now underweighted in portfolios relative to what’s desirable from a portfolio construction perspective and therefore could be useful diversifiers. I know gold sounds like a kooky investment. But gold is just an alternative currency to fiat paper currencies. If your portfolio is likely to perform poorly in the adverse environment I’ve been describing—less effective monetary policy, the need to run larger fiscal deficits and monetize them, and challenging politics—the behavior of gold as alternative cash has some diversifying merit.

Most investors are also significantly underweighted in Chinese stock and bond markets, which has left prices of these assets lower than they otherwise would be. Such investments are controversial at the moment given the geopolitical tensions. But, even beyond that, investors are generally uncomfortable gaining exposure to markets they haven’t been in before, and tend to put too much weight on cap-weighted approaches. In my experience, that’s been a mistake. I have repeatedly seen investors get comfortable with new markets once they finally dip their toes in; I even remember when pension funds thought it was too risky to go into equities from bonds. I think investors are showing a similar hesitancy toward China today.

I believe that will change. China’s markets are now big. Their equity and bond market caps are second to the US; they are growing fast and will be increasing in size in the benchmark indices, so foreign investments in them will pick up. I’d rather be ahead of these flows than behind them. And, from a diversification perspective, if any competitor is likely to erode US market share, it will be China. I think if investors look back on this moment one day in the distant future and see that they didn’t have any exposure to China at the beginning of the 21st century—when China is already the second largest economy, and it and its markets are growing fast—they’ll regret it.

Most importantly, balancing the sizes of one’s exposure to different markets that are already in one’s portfolio is the most powerful way of bringing about better diversification without reducing expected returns. In my opinion, balancing risk in these ways is the most crucial thing an investor can do in the current environment.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/30vFXgq Tyler Durden