Here Is The Megabank Behind September’s Repo Shock

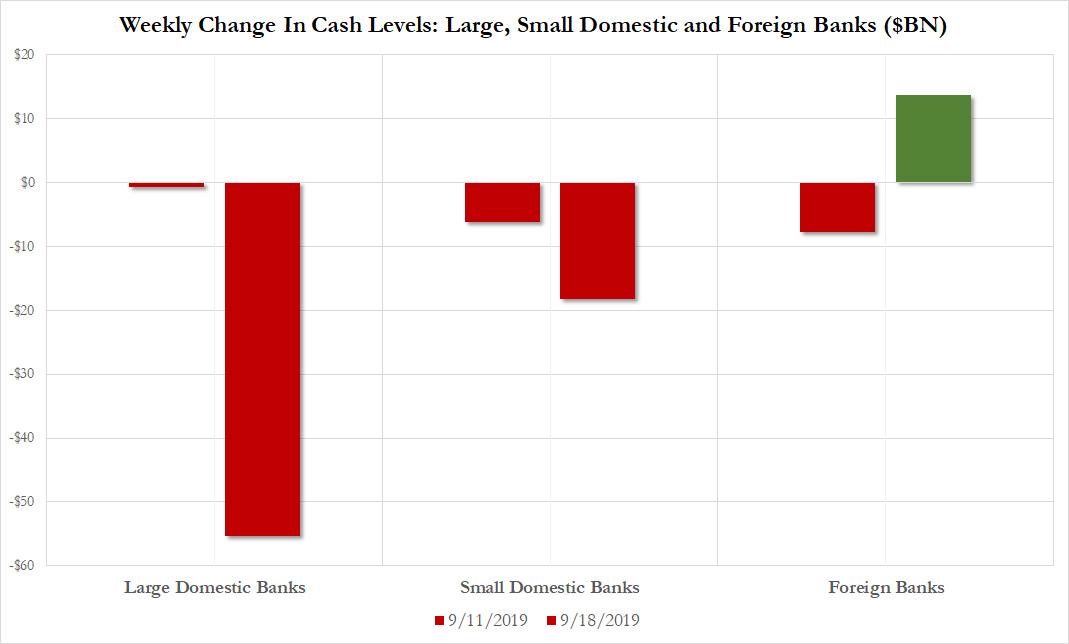

Over the weekend, when trying to isolate the bank(s) behind the recent repocalypse, we looked at the aggregate cash levels of commercial banks in the US (which including foreign banks) as published each week by the Fed, and found that cash at foreign banks operating in the US rose by a respectable $13.6BN in the week ended Sept 18, to $537,8BN, in line with levels where foreign bank cash had been for much of the past two months.

“In other words”, we wrote “to find the culprit for the latest repo shock, don’t look to Europe (those banks have enough pain on their plate with the ECB recently launching QEternity, to also have to worry about overnight funding in the US) but look for clues among domestic US banks. “

Three days later, Reuters did just that, and in a report which surprisingly flew deep under the radar, appears to have found the one bank that may have been the inadvertent reason for the repo market to lock up on the 11th anniversary of Lehman when the repo rate exploded as high as 10%.

According to Reuters, “JPMorgan Chase has become so big that some rival banks and analysts say changes to its $2.7 trillion balance sheet were a factor in a spike last month in the U.S. “repo” market, which is crucial to many borrowers.“

As a reminder, just days after the record repo rate surge, a clearly clueless NY Fed president John Williams told the FT in an interview that the Fed was examining “why banks with excess cash failed to lend to the overnight money market, following a week that revealed cracks in the US’s financial plumbing.“

The answer: big changes JPMorgan made in its balance sheet “played a role in the spike in the repo market.”

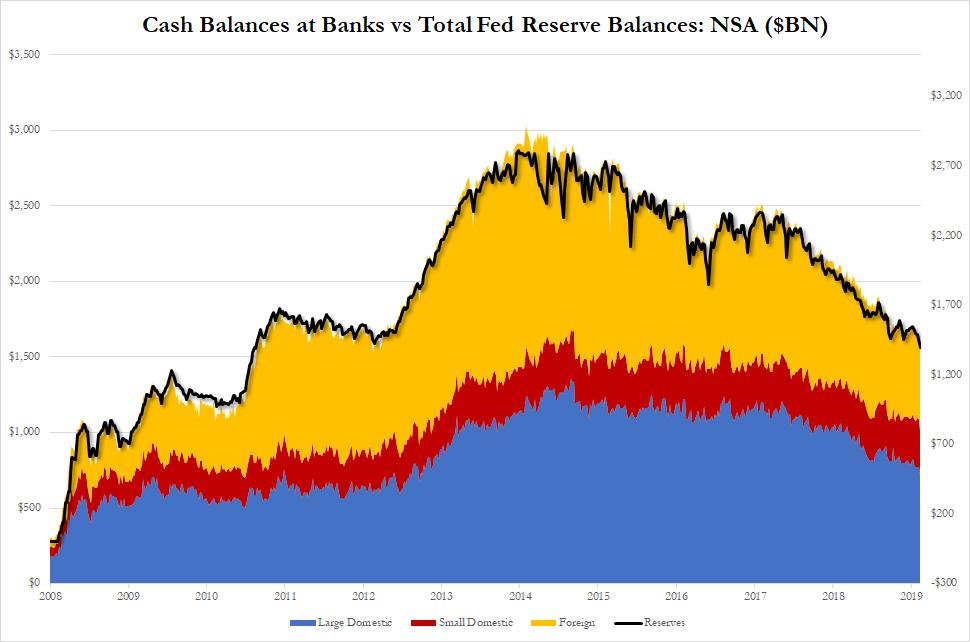

Specifically, using public data, and conducting an analysis similar to the one we did last weekend tracking commercial bank cash levels, Reuters found that JPMorgan reduced the cash it has on deposit at the Federal Reserve, from which it might have lent, by $158 billion in the year through June, a 57% decline.

While JPMorgan’s moves were seen as logical responses to interest rate trends and post-crisis banking regulations, which have limited it more than other banks, “the data shows its switch accounted for about a third of the drop in all banking reserves at the Fed during the period”, Reuters adds. As a reminder, the recent slide in bank cash levels took the Fed’s reserves to the lowest level since 2012:

“It was a very big move,” said a Reuters source who watches bank positions at the Fed but did not want to be named. An executive at a competing bank called the shift “massive.”

And while other banks also brought down their cash, it was by only half the percentage, on average, according to Reuters calculations. One of them, Bank of America, the second-biggest U.S. bank by assets, with a $2.4 trillion balance sheet, took down 30% of its deposits, a $29 billion reduction, less than a fifth of JPM’s cash decline.

JPMorgan or not, as we showed for the past two weeks, total deposits at the Fed from banks have come down sharply over the past year as a consequence of the central bank’s decision to gradually reduce the vast holdings of bonds it had acquired to bolster the economy after the financial crisis: the reason is simple – as the Fed tapered its bond portfolio as part of QT, its deposits from banks have also declined.

“All of the banks were doing this to a degree,” said one Wall Street banking analyst, requesting anonymity because he was not authorized to speak on the record, adding: “JPMorgan does look like an outlier here.”

Ok, so we now know we can blame JPMorgan for not stepping up when the bank with the largest cash balances at the Fed clearly should have. But why?

Well, whereas in the past JPMorgan would have “gladly seized the opportunity to lend cash in the repo market, where loans are backed by the best collateral, often U.S. Treasury securities”, on on Sept. 17 even as the majority of repo loans were being made at 5% and above, twice the usual rates, “JPMorgan was limited in how much of its remaining cash it could provide because of regulatory and other constraints.”

The spike in rates reflected extra demand for cash, which was widely anticipated due to corporations requiring cash to make scheduled tax payments and banks and other firms needing it to buy newly-issued U.S. Treasury securities.

In other words, without the regulatory requirements and official constraints – most of which are created by the Fed itself – on JPMorgan, the rate wouldn’t have spiked to 10%, the person said.

Ironically, it was JPMorgan that made the biggest draws from the Fed late last year and bought securities, winning praise from analysts for locking in fixed interest rates before Federal Reserve cuts. Buying the securities also offset pressure on JPMorgan’s mortgage loan portfolio from falling rates. JPMorgan also needs cash for sudden demands by corporate depositors and to meet government requirements for reserves on checking account deposits.

It is this cash level that regulators now oversee to make sure there is no repeat of the cash crunch that took place during the 2008 financial crisis; as a result JPM must comply with rules which require banks to keep additional cash in case they fail and the government needs to transfer their operations in viable condition to other firms. Banks do not disclose how much of this so-called resolution cash they must hold, but the amount is clearly significant if $1.4 trillion in “excess” reserves turned out to be woefully insufficient.

Another post-crisis regulation imposes a capital surcharge on banks that are most important to the global financial system and it gives JPMorgan particular reason not to make repo loans going into the last three months of the year.

That is especially true for repos with firms from abroad, which include U.S. branches of foreign banks and Cayman Islands-registered hedge funds. Such loans could push JPMorgan’s surcharge higher, requiring it to carry an additional $8 billion of capital, a Goldman Sachs report said.

According to Goldman, JPMorgan’s capital surcharge is already the highest of any U.S. bank, which means its must make more profit from its business to produce the same return on shareholder equity.

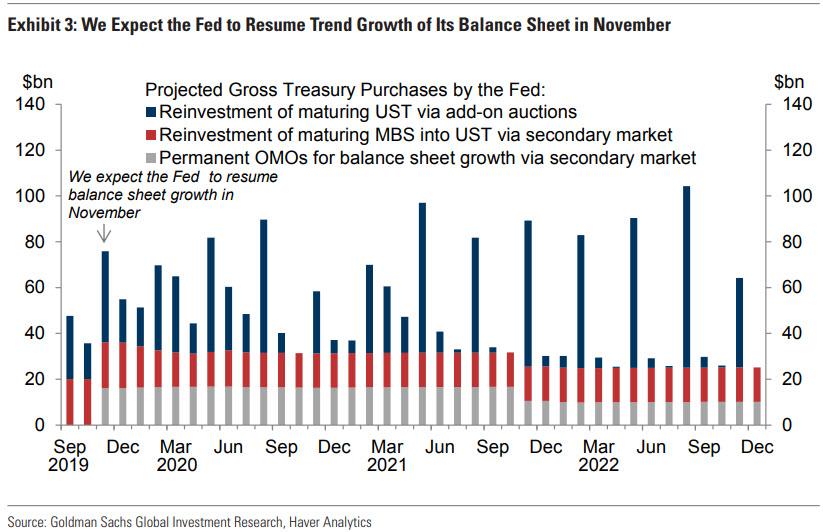

Separately, as we reported before, Goldman analysts see the repo market pressures continuing under the regulatory constraints and what they believe is a shortage of extra cash on deposit at the Fed. Their solution: resuming Treasury purchases by the Fed, which they believe should conduct roughly $15bn/month rate of permanent OMOs, enough to support trend growth of the balance sheet plus some additional padding over the first two years to increase the size of the balance sheet by $150bn, restoring the reserve buffer and eliminating the current need for temporary OMOs. Altogether, this would boost the Fed’s balance sheet by a total of $180bn/year and result in net UST purchases by the Fed (the sum of the red and grey bars) of roughly $375bn/year over the next couple of years. When netting the purchases to rollover maturing debt, the monthly total rises to about $20BN/month on average.

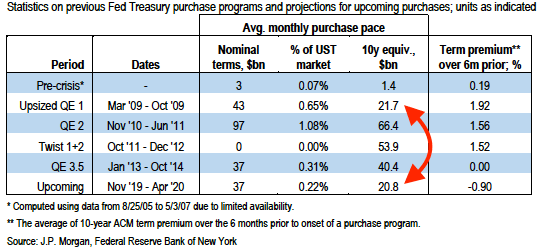

For those asking, the $20BN in soon to be announced monetizations is virtually the same as the total debt purchased under the fully-upsized QE1 which was launched in response to the financial crisis, as the following JPMorgan chart shows:

Just whatever you do, “don’t call it QE” or someone may get the impression that the Fed is once again in the bank bailout business…

Tyler Durden

Wed, 10/02/2019 – 14:55

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2pt0Xr9 Tyler Durden