Lawmakers from California to Washington, D.C., are still busy dining out and socializing, even as that option disappears for more and more ordinary Americans.

Prompted by a rise in coronavirus cases, the country’s mayors and governors are imposing new restrictions on bars and restaurants, including curfews and the forced shuttering of indoor dining rooms. These are yet another setback for businesses that already went through one prolonged shutdown in the spring, and that are now heading into winter without knowing when they’ll be able to serve customers inside again.

“My first reaction probably contains some expletives in my head,” says Anthony Hansen Mairs, a manager of the distillery Crater Lake Spirits in Bend, Oregon, when reacting to a Friday public health order from Oregon Gov. Kate Brown (D) banning bars and restaurants from serving customers onsite for at least the next two weeks. Instead, they’ll be limited to offering takeout and delivery.

The order means Crater Lake Spirit’s tasting room—which had already been closed for a couple of months earlier this year—will have to shut down again.

Hansen Mairs says that he is hoping to keep his tasting room team of 12 paid during the two-week shutdown and that the production side of the distillery has enough work to keep them employed at least through the end of the year.

The closure of the tasting room comes with costs for the company’s workers who relied on tips they earned serving drinks there. “There are some nights where I might make $80 in my wage and $120 in tips. That’s not always how it is, but it’s a good portion of the income from that job,” says Ross Orndorff, one of the tasting room staff. (Disclosure: Orndorff is a former roommate of mine). Working on the distillery’s production line comes with more predictable hours, but won’t make up for all that lost income, Orndorff says.

“There’s still the air of doubt that this will only be two weeks,” adds Hansen Mairs, telling Reason that the longer the shutdown goes on, the more likely it is that they’ll have to lay off some employees.

Other bars and restaurants that don’t have a distillery business to fall back on are in much worse shape.

“We were already hearing from members they were concerned about what another shutdown would do to their chances of staying open,” said Jason Brandt, president and CEO of the Oregon Restaurant & Lodging Association (ORLA), in a press release criticizing Brown’s order. “This latest round of regulations focused on restaurants will trigger an unknown amount of permanent closures impacting the livelihoods of thousands of Oregon families.”

That economic pain is likely to be replicated across the country as more and more places return to the lockdown policies from earlier in the pandemic.

On Monday, Philadelphia issued a new public health order closing down indoor dining, alongside gyms and movie theaters. Last week, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) ordered bars and restaurants in the state to close at 10 p.m. as Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam (D) mandated that eating and drinking establishments stop serving alcohol by 10 p.m. and close by midnight.

The most dramatic rollback of business reopenings is happening in California. As of Monday, climbing case numbers have forced most counties into the most restrictive tier in the state’s four-tiered reopening scheme. That means bars and indoor dining rooms in most parts of the state will have to close.

San Francisco has been ahead of the curve in reinstituting business closures. Last week, Mayor London Breed issued an order requiring all indoor dining in the city to close over the weekend, even though the city still qualified for the state’s least restrictive tier at the time.

“If this closure does stay in place, it’s going to have devastating consequences,” says Laurie Thomas, the owner of two restaurants in San Francisco and executive director of the Golden Gate Restaurant Association (GGRA).

Breed’s order, issued on Wednesday of last week, came as a shock, says Thomas. The city had previously committed itself to lag behind the reopening conditions by one tier set by the state. For example, in late September, the city allowed indoor dining rooms to open at 25 percent, despite the state allowing indoor dining at 50 percent capacity.

As of last Monday, the city was in the state’s “red” tier, which allows indoor dining at 25 percent capacity. A rapid increase in new cases prompted Breed, acting on the advice of city public health officials, to shut down all indoor dining and impose new capacity limits on gyms and movie theaters.

“With this decision,” says Thomas “there was not much notice for restaurants to one, absorb this information, and two, take actions to stop financial losses that occur when you cut back.”

Suddenly having to close down is not great for any business. It’s particularly costly for restaurants that operate on slim margins in the best of times, and who face massive closing and reopening costs.

“It’s not like having any other type of business. You have to buy a significant amount of inventory. That inventory is really volatile,” says David Nayfeld, chef and co-owner of two restaurants in San Francisco. When reopening, staff often have to be retrained and the restaurant must be prepped to receive customers again, he adds. “You have all this labor cost that’s going out before you even make a dollar.”

To take on all those costs of reopening and then be forced to close down again runs counter to everything that goes into running a profitable restaurant, says Nayfeld. “There’s constant stutter steps. We’re buying inventory then it goes thrown away. All the money is getting thrown out the window.”

For that reason, he says his own businesses didn’t jump on the opportunity to reopen indoor dining when it was allowed, saying that they’d planned on waiting to see how things went when the city allowed 50 percent indoor dining capacity.

The city had been scheduled to allow dining rooms to open at 50 percent capacity in November, but that was delayed in late October, reports the San Francisco Chronicle. Following the most recent shutdowns, it’s not clear when restaurants will be allowed to welcome diners back inside again.

Thomas says she understands where San Francisco’s public health officials are coming from when ordering restaurant closures—the city has reported a 250 percent increase in new cases since the beginning of October—but still thinks they were being too hasty.

“They’re trying to pull the levers they have in front of them to dampen the speed in the increase of the cases. They are truly afraid that this represents an uncontrollable spike,” she said last Thursday. “I want to revisit where we’re at on Monday, and still see if there’s that need. I would have liked to have waited through this week” before closing indoor dining.

More energy, she added, should be spent alerting the public to the dangers of house parties and private gatherings.

In recent days, public health officials have been beating that drum. California’s Health and Human Services Secretary Dr. Mark Ghaly says that county officials in the state are reporting “private household gatherings as a major source of spread,” according to The Guardian.

“We are increasingly observing this fall that transmission is happening in small gatherings related to youth sports or among family and friends in their homes,” wrote several doctors in a blog post at the Children’s Hospital of Philidelphia’s PolicyLab.

“Earlier in the outbreak, much of the growth in new daily cases was being driven by focal outbreaks—long-term care facilities, things of that nature,” said an official with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to The Washington Post last week. “Now, the kitchen table is a place of risk.”

The role that private gatherings are playing in spreading the pandemic is seeing some public health experts question the wisdom of the recent wave of business closures and restrictions.

“It’s like you’re taking a sledgehammer to the problem; it’s not very fine-tuned,” said Peter Chin-Hong, a professor and infectious disease expert at the University of California, San Francisco, of Newsom’s latest restrictions, to the Associated Press. “It doesn’t address where a lot of the catalysts are for transmission.”

Indeed, restaurant closures might even be counterproductive. If people aren’t allowed to socialize in a sanitized, socially distanced, well-ventilated restaurant, they might be more likely to gather in private homes that might not have any of those measures in place.

Business advocates haven’t been shy about drawing attention to this discrepancy.

“Knowing small social gatherings are the focal point for the transmission of this virus, it is incredibly disappointing to see our industry once again targeted,” said Brandt in response to Oregon’s closures.

The latest shutdowns have also reinvigorated calls from the restaurant industry for additional government aid. ORLA is asking for the creation of a $75 million relief fund for the state’s hospitality industry. Breed, when shutting down indoor dining, announced that the city would make available $4 million in aid to restaurants and small businesses.

Nayfeld, who also serves on the advisory board of the Independent Restaurant Coalition (IRC), says that much, much more is needed. With the IRC, he’s been advocating for the passage of the RESTAURANTS Act, which would create a $120 billion federal assistance fund for distressed restaurants.

That would give restaurants the financial security they need to ride out the pandemic, he says. It would also compensate them for the losses they’ve incurred from government-ordered shutdowns and other measures they’ve taken to keep the public safe.

Some libertarian policy experts are divided on the subject of aid to restaurants and other small businesses affected by government shutdowns.

“Evidently, the case for some sort of aid from the government is stronger when the government in question is explicitly closing down businesses and preventing them from trading,” says Ryan Bourne, an economist with the Cato Institute.

On the other hand, policy makers “have no concept of how much this pandemic will change the demand for eating out,” says Bourne.

A federal aid package like the RESTAURANT Act would “entail subsidizing businesses that may well not be viable in the near future, and that comes with an economic cost. It will take us longer for the economy to adjust to its new condition after the pandemic,” Bourne says.

An alternative response would be to let restaurants figure out if it’s profitable and safe to operate during the pandemic, and to let customers decide whether the risks of eating out are worth it. If private gatherings are going to continue to undo sacrifices in other parts of the economy, it’s harder to justify restrictions on any specific sector.

Still, even in the absence of shutdowns, the natural impulse to curtail socializing and other voluntary activities in the middle of a pandemic is going to cause the hospitality industry to suffer business closures and job losses, says Bourne.

“What’s going to get the economy going is the end of this pandemic. [We should do] anything we can do to hasten the end of this pandemic, whether that’s greasing the wheels for rolling out the vaccine, whether it’s facilitating, through lowering regulatory barriers, more in the way of rapid testing and screening.”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2UHWQUd

via IFTTT

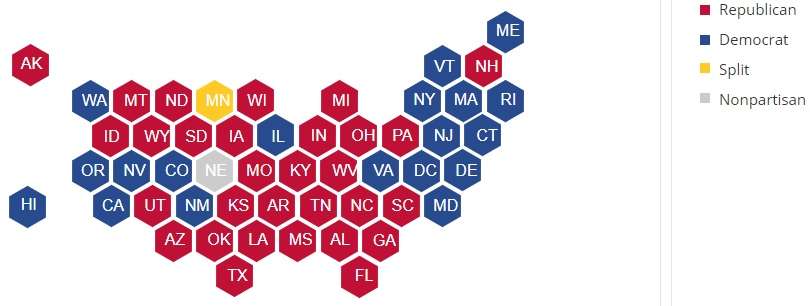

See here, with a before and after map of partisan control (the after map is above). Some highlights:

See here, with a before and after map of partisan control (the after map is above). Some highlights: