In the halcyon days of yore—you know, 10 weeks ago—budget hawks were fretting about the return of trillion-dollar deficits, with the Congressional Budget Office’s latest 10-year projection showing that the annual budget deficit would hit $1.7 trillion by 2030.

Today, that projection is not even worth the paper it is printed on.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic that has already prompted Congress to hike spending by $2.2 trillion (with more likely on the way), and with revenue collections likely to drop in a big way as a result of the coronavirus-induced economic shutdown, the federal government is facing the prospect of a budget deficit of nearly $4 trillion this year. That’s according to several independent projections made by various organizations over the past week.

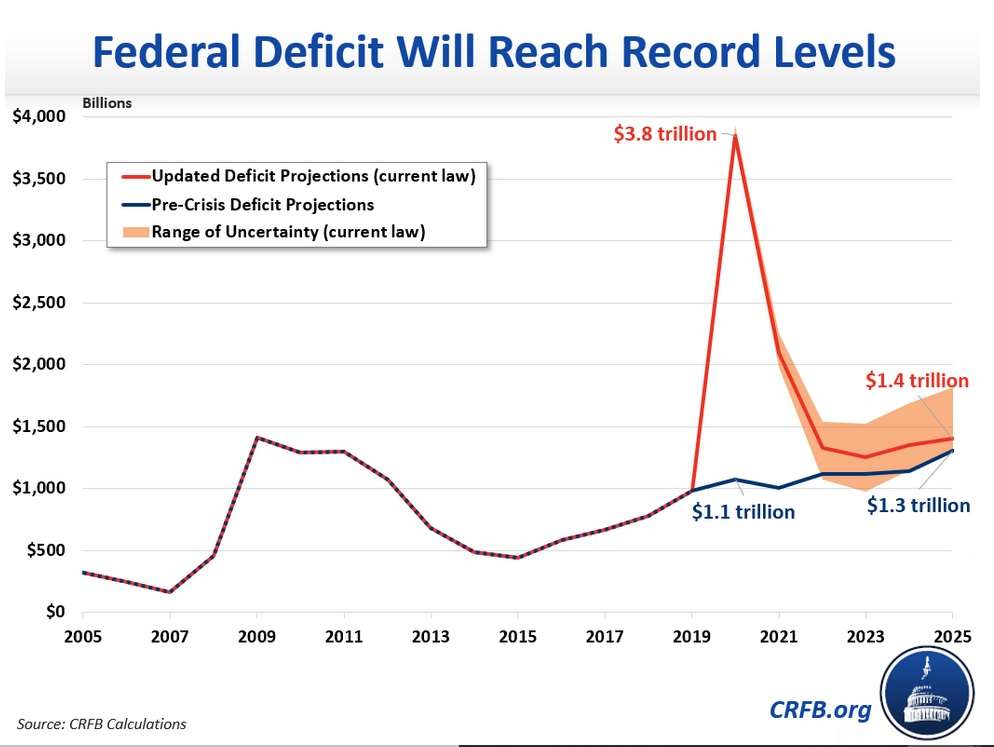

The numbers are truly staggering. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), a nonpartisan group that advocates for lower deficits, the budget deficit will hit $3.8 trillion this year—that’s four times larger than the $984 billion deficit recorded last year. The exploding deficit will cause the national debt to exceed the size of the entire U.S. economy this year, something that has not happened since the height of World War II.

And it is almost certainly a best-case scenario. “These projections almost certainly underestimate deficits, since they assume no further legislation is enacted to address the crisis and that policymakers stick to current law when it comes to other tax and spending policies,” the CRFB said in a statement. “The projections also assume the economy experiences a strong recovery in 2021 and fully returns to its pre-crisis trajectory by 2025.”

If that happens, annual budget deficits will fall to about $2 trillion next year and to $1.3 trillion in 2025. For comparison’s sake, the largest since-year deficit during the Great Recession that followed the 2008 economic crisis was $1.3 trillion.

But even if deficits recede to merely pre-coronavirus record highs, the national debt will continue to exceed the size of the U.S. economy for the immediate future, the CRFB projects.

Other budget-watchers have come to similar conclusions. Investment bank Goldman Sachs is now expecting a $3.6 trillion federal deficit this year. G. William Hoagland, a senior vice president of the Bipartisan Policy Center and a former Senate GOP budget aide, told Roll Call that he expects a deficit of $3.9 trillion. Romina Boccia, research director for the Heritage Foundation’s Center for the Federal Budget, told Fox News that the deficit will likely exceed $3.5 trillion.

“There’s the real risk, of course, that we might be teeing up a public debt crisis on the other end of this,” Boccia told Fox. That, she added, would likely mean higher taxes, reduced government services, inflation, and economic stagnation.

Just as the heavy borrowing that took place during the Great Depression and World War II was followed by a period of fiscal restraint to bring deficits back in line, the CRFB says, so too must policy makers prioritize deficit reduction once the current public health crisis has passed. “Putting long-term deficit reduction measures in place sooner rather than later would allow policymakers to phase in changes more gradually and give those affected more warning and ability to prepare,” the CRFB advises.

The CBO has yet to publish an updated projection that takes last month’s passage of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act into account. By the time it does, that projection might be out of date, too. Already, President Donald Trump and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D–Calif.) are discussing plans for another trillion-dollar (maybe $2 trillion) stimulus package.

And the coronavirus is expected to wreak havoc on state budgets as well, raising the prospect that the federal government may have to use its credit card to bail out some states too. The National Governors Association is already asking for $500 billion.

In other words, 10 weeks from now, we might be wishing for the days when the federal deficit was only $4 trillion.

“The $5 trillion number, adjusted for inflation, would also be more than five times the amount spent on the entire New Deal in the 1930s.”

And I got pummeled ???? by Republicans and Democrats for suggesting this should be a recorded vote! ????♂️ https://t.co/zFuz2SMLD7

— Thomas Massie (@RepThomasMassie) April 10, 2020

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2xv10XB

via IFTTT