Reason‘s December special issue marks the 30th anniversary of the collapse of the Soviet Union. This story is part of our exploration of the global legacy of that evil empire, and our effort to be certain that the dire consequences of communism are not forgotten.

It was the summer of 1983, and I, a Soviet émigré and an American in the making, was chatting with the pleasant middle-aged woman sitting next to me on a bus from Asbury Park, New Jersey, to Cherry Hill. Eventually our conversation got to the fact that I was from the Soviet Union, having arrived in the U.S. with my family three years earlier at age 17. “Oh, really?” said my seatmate. “You must have been pretty offended when our president called the Soviet Union an ‘evil empire’! Wasn’t that ridiculous?” But her merriment at the supposed absurdity of President Ronald Reagan’s recent speech was cut short when I somewhat sheepishly informed her that I thought he was entirely on point.

In 1983, the 61-year-old empire looked like it would be eternal. My next memorable conversation about the Soviet Union with a fellow passenger, in December 1991, proved otherwise. I was aboard a flight from Moscow to Newark, New Jersey, after a two-week visit, waiting for takeoff. “Do you know that the Soviet Union doesn’t exist anymore?” the man next to me said. I stared. He showed me that day’s International Herald Tribune with a headline about the Belovezha Accords, an agreement by which the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus agreed to dissolve the USSR.

The evil empire was over.

The Gulag Empire

The woman on the bus in 1983 did not surprise me. By then, I had already met many Americans for whom “anti-Soviet” was almost as much of a pejorative as it had been in the pages of Pravda, the official newspaper of the Soviet Communist Party. My favorite was a man in the café at the Rutgers Student Center who shrugged off the victims of the gulag camps by pointing out that capitalism kills people too—with cigarettes, for example. When I recovered from shock, I told him that smoking was far more ubiquitous in the Soviet Union, and anti-smoking campaigns far less developed. That momentarily stumped him.

My mother was also at Rutgers at the time as a piano instructor. She once got into a heated argument over lunch with a colleague and friend after he lamented America’s appalling treatment of the old and the sick. She ventured that, from her ex-Soviet vantage point, it didn’t seem that bad. “Are you telling me that it’s just as bad in the Soviet Union?” her colleague retorted, only to be dumbstruck when my mother clarified that, actually, she meant it was much worse. She tried to illustrate her point by telling him about my grandmother’s sojourn in an overcrowded Soviet hospital ward: More than once, when the woman in the next bed rolled over in her sleep, her arm flopped across my grandma’s body. Half-decent care required bribing a nurse, and half-decent food had to be brought from home. My mother’s normally warm and gracious colleague shocked her by replying, “I’m sorry, but I don’t believe you.” Her perceptions, he told her, were obviously colored by antipathy toward the Soviet regime. Eventually, he relented enough to allow that perhaps my grandmother did have a very bad experience in a Soviet hospital—but surely projecting it onto all of Soviet medicine was uncalled for.

It wasn’t just the campus lefties. The Twitter generation may believe that mainstream American culture at the time was in the grip of Reaganite anti-communism, but some of us remember differently. Media coverage of Soviet human rights abuses, for instance, was frequently accompanied by reminders that the United States and the Soviet Union simply had “fundamentally different perceptions of human rights,” as U.S. News & World Report put it in 1985: “To the Kremlin, human rights are associated primarily with the conditions of physical survival.” A 1982 guide for high school study of human rights issued by the National Council for Social Studies even suggested that it was “ethnocentric” to regard “our” definition of human rights as superior to “theirs.”

As Soviet society began to open up under Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost (a term that means something like “openness and transparency,” and that one Soviet dissident defined as “a tortoise crawling towards freedom of speech”), more information began to come out in the Soviet press that cast serious doubt on the Soviet Union’s supposed gains on the social welfare side of “human rights.” There were stories about the dismal state of Soviet medicine, about crime, about millions condemned to appalling living conditions, about Dickensian orphanages sheltering abused and malnourished children, and about homeless people who suddenly turned out to exist, despite prior reports to the contrary. (The weekly newspaper Argumenty i Fakty reported that 174,000 vagrants were picked up in 1984 alone.) Meanwhile, the regime was crumbling; as satirist Victor Shenderovich put it later, “the country still had Soviet power but the food had already run out.”

In just a few years, Soviet communism was relegated, just as Reagan had predicted to much ridicule, to “the ash heap of history.” The leaders of the new Russia that emerged in its place themselves echoed the language of “evil empire” when they spoke of the Soviet past: During the 1996 elections, President Boris Yeltsin told supporters at a campaign rally they had to win “so that Russia can never be called an evil empire again.”

For leftists who still saw communism as a noble dream, this was a devastating defeat. In 1999, at the close of what was, in a very real sense, the Soviet century, the Polish-American socialist journalist Daniel Singer—himself the son of a gulag survivor—wrote in The Nation that a reckoning with communist atrocities was necessary; but he also rejected the “corpse-counting” of The Black Book of Communism, a collection of historical essays that sought to chronicle those atrocities. Singer took the authors to task for reducing communism’s record to “crimes, terror and repression.”

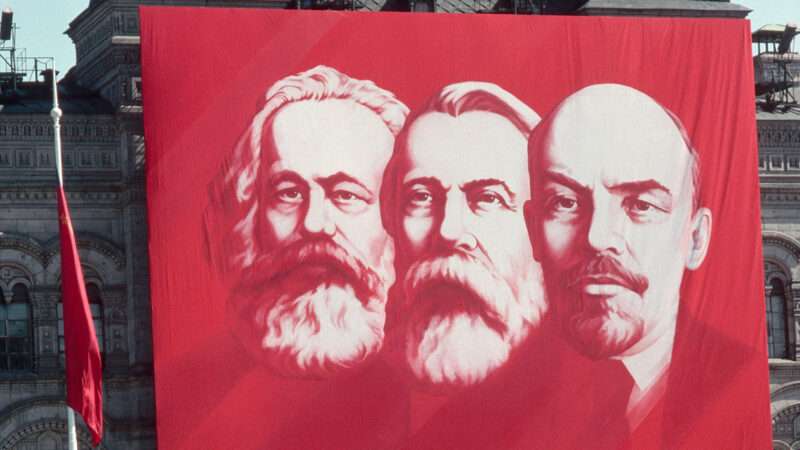

“The Soviet Union did not rest on the gulag alone. There was also enthusiasm, construction, the spread of education and social advancement for millions,” Singer asserted, lamenting that the Black Book approach made it impossible to “comprehend why millions of the best and brightest rallied behind the red flag or…turned a blind eye to the crimes committed in its name.” (It was apparently not satisfying to answer with the pithy phrase coined by statistician and essayist Nassim Nicholas Taleb: Because they were “intellectuals-yet-idiots.”)

As the new century rolled onward, the Soviet Union was still dead, but it turned out to be an unquiet ghost. The new man at Russia’s helm, career KGB officer Vladimir Putin, brought back the Soviet anthem (albeit with new lyrics about God and Russian greatness) and the red flag as the Russian Armed Forces banner, working to make Soviet nostalgia respectable—albeit in a weird blend with Russian nationalism, Orthodox Christianity, and reverence for the czars. An idealized image of Soviet communism also bubbled back up among progressives in the West, especially after the reputation of democratic capitalism was left tarnished by the war in Iraq and the Great Recession. “Neoliberalism” was out; “socialism” was in: From 2010 onward, 49 percent or larger portions of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents and of adults under 30 have said they have a positive view of socialism. By the end of the decade, even communism was surging in popularity: It was viewed favorably by 36 percent of millennials (up from 28 percent in 2018) and 28 percent of Generation Z.

Soviet-style communism is also getting favorable press in progressive venues—from the trollish Chapo Trap House podcast to Salon (“Why you’re wrong about Communism”) to radical chic playpen Teen Vogue, which hailed Karl Marx for his 200th birthday in 2018 as a thinker who “inspired social movements in Soviet Russia, China, Cuba.” On the opinion pages of The New York Times, Kristen Ghodsee, a professor of Russian and East European studies at the University of Pennsylvania, dubiously declared that women had better sex under Soviet-style socialism, a thesis she then expanded into a slim book lauding communist strides toward gender equality. Even The New Republic, once a bastion of liberal anti-communism, jumped on the bandwagon in 2016 with “Who’s Afraid of Communism?” by former Occupy Wall Street activist Malcolm Harris, who zinged Hillary Clinton for her old-fashioned Cold Warrior mentality and argued that communism was getting a bum rap, given the Soviet Union’s heroic role in the victory over Nazism and the key contributions of communists to “liberation” struggles all over the world.

On social media today, “tankies” with hammer-and-sickle emojis in their usernames and Marx or Lenin profile headers are a loud and proud faction of lefty Twitter. These are overwhelmingly young people, in their 20s and sometimes late teens, steeped in the racial and sexual identity politics of their generation of activists, often sporting gender pronouns and rainbow flags in their bios along with the communist symbology. Many seem convinced that actual Soviet-style communism—not just the “hasn’t been tried” utopian ideal—was an admirable vision. “The more I read about the Soviet Union the more obvious it becomes why the west had to demonize it,” writes a “queer,” “anti-imperialist” Twitter user with the colorful moniker “hezbolleninism.” “The USSR’s ideology was not only a threat to capitalism, it was a threat to white supremacy.”

A Picture of Prejudice

Not surprisingly, like the 20th century “political pilgrims” (as author Paul Hollander called them) who traveled to the Soviet Union or Cuba and came back with glowing reports, the 21st century communist nostalgics often have a tenuous connection with reality.

Hezbolleninism’s tweet, for example, featured a screenshot from the 2018 book Politics and Pedagogy in the ‘Post-Truth’ Era: Insurgent Philosophy and Praxis (Bloomsbury Academic) by Derek R. Ford, a professor of education studies at DePauw University in Indiana, discussing anti-racism in the Soviet Union. Ford describes a 1930 incident involving “Robert Robertson, a Jamaican native and U.S. citizen” who came to work at a tractor factory in Stalingrad alongside a few hundred white American technicians. (The Soviets were strenuously recruiting foreign and especially American specialists, since Lenin’s prediction that the new regime would quickly train its own cadre with proletarian backgrounds and impeccable Bolshevik convictions had proved a tad overconfident.) On his first day, the black worker was roughed up by two white Americans when he tried to eat in the American dining hall. The assault was widely publicized and denounced at factory meetings around the Soviet Union; the attackers were convicted of “white chauvinism” at a show trial and sentenced to two years of imprisonment (commuted to 10 years banishment from the Soviet Union). “Robertson remained in the Soviet Union, where he eventually gained citizenship,” reports Ford, for whom this episode demonstrates “the seriousness with which the Soviet Union—its people and its state—took racism.”

But Ford left out the end of the story. After becoming a Soviet citizen, Robinson (yes, Ford got the name wrong) spent decades trying to get out of the supposed anti-racist paradise. He finally managed it in 1974, when he obtained permission to travel to Uganda as a tourist and never returned. He eventually made it to the U.S., regained his citizenship in 1986, and wrote a scathingly anti-Soviet 1988 memoir titled Black on Red. Robinson conceded that the Soviet Union gave him professional opportunities he probably would not have had as a black American in that era. But he also described the ordeal of the Great Terror, when his friends and colleagues were disappearing one after another, as well as casual and not-so-casual encounters with racism.

Robinson’s Soviet saga is richly illustrative of Soviet “anti-racism,” deployed almost exclusively as a weapon with which to bludgeon the Americans (and more generally the West). Black people were useful insofar as they advanced the communist cause, but they were treated more as white-savior projects than as human beings in their own right.

Likewise, the African students who began to attend Soviet universities in the 1960s as part of the USSR’s outreach to newly decolonized African countries tended to be viewed by their hosts as backward, needy, and often ungrateful recipients of Soviet largesse. In a fascinating 2014 article in the journal Diplomatic History, Russian studies scholar and podcaster Sean Guillory writes that the Africans were given insultingly easy entrance exams with elementary school–level math problems, while their complaints of racist harassment were generally shrugged off as hypersensitivity bred by colonialist oppression. Meanwhile, grassroots Soviet humor generated its share of extremely nasty jokes (which circulated freely at my school in the 1970s) depicting the Soviet Union’s African guests as simple-minded savages, perpetually horny for white women and literally related to monkeys.

Anti-black racism was just part of a bigger picture of prejudice. As early as 1926, the Soviet regime began to plan the removal of ethnic Koreans living in the Soviet Far East, who were seen as a threat who might work with the Japanese to undermine the Soviet Union. Deportations began slowly, until 170,000 people were forcibly moved to Central Asia in 1937. While parallels to the internment of Japanese Americans in the United States are obvious, the Soviet version was far deadlier: estimates of the death toll from malnutrition, illness, and exposure (with the deportees transported in unheated cargo cars in cold weather and resettled in hastily constructed barracks or huts) range from 16,500 to 50,000. This ethnic cleansing was followed by others in the 1940s: Kalmyks, Crimean Tatars, Chechens, and other ethnicities were collectively branded as Nazi collaborators and brutally relocated. Some were allowed to return after Josef Stalin’s death; others, such as the Crimean Tatars, were not.

Anti-Asian prejudice soared after the Sino-Soviet split, with rabid propaganda depicting the Chinese as the ultimate enemy and generating genuine paranoia about a Chinese invasion. As often happens, anyone who looked Chinese was fair game. My mother once heard a shopper at a Moscow farmers market shout to a vendor, “You! Chinaman! How much for your apples?” When the vendor defensively replied that he was Kazakh, the woman retorted, “Yeah, I know you’re not a Chinaman. If I thought you were, I’d bash your head in.”

And that’s not to mention the anti-Semitism that culminated in the campaign against “cosmopolitans” and Zionists in Stalin’s final years, but continued in more low-key ways for decades after that. Discrimination against Jews in college admissions was so common that it was reflected in numerous jokes (e.g., one in which an ethnic Russian taking a college entrance history exam is asked for the year of the sinking of the Titanic while a Jewish applicant is told to list all the casualties by name). The brother of one of my mother’s piano students got a failing grade on the entrance exams despite a brilliant academic record; after his father got an influential professor to intervene, it turned out that the examiner thought he looked Jewish. In deference to the professor, the examiner agreed to change the failing grade but irritably remarked, “Just don’t tell me he’s not a Jew—I’m not stupid!”

On a more basic level, Soviet anti-Zionist propaganda trickled down into a casual anti-Semitism that regularly manifested itself in harassment and even violence. Thankfully, my own bad experiences were very minor (a boy in my building shouting “You miserable Jew-girl!” during a playground conflict; a drunk at a bus stop ranting about Jews). But my parents endured several years of abuse by a Jew-hating neighbor in a communal apartment before they were finally able to move out. Other people had harrowing stories of children being tormented at school by anti-Semitic bullies who acted with impunity. A fellow émigré I met in the U.S. told me her decision to leave was solidified when she learned that her teenaged son had started carrying a knife to school for self-defense.

Ironically for American leftists, the dominant Soviet attitude toward race and ethnicity was precisely the sort of see-no-evil faux colorblindness that progressives love to denounce in the U.S. context. In nine and a half years of Soviet schooling, I sat through numerous lectures on proper Soviet values and only ever heard racial or ethnic prejudice mentioned as an example of Bad Things Over There In America.

Even the enemy’s racism could be downplayed if convenient: Witness the Soviet authorities’ systematic erasure of the Jewish Holocaust in discussing Nazi atrocities. This adds an ironic asterisk to the praise often heaped on the Soviet Union for its role in defeating the Nazis. Yes, Soviet forces liberated Auschwitz, but the official Soviet report on its horrors described the victims as “citizens of the Soviet Union, Poland, France,” and others, with just one specific mention of Jews—a passing reference to “a Jewish woman named Bella” in an excerpt from a survivor’s statement. In 1961, the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko was briefly “canceled,” as we would say nowadays, for “fomenting ethnic division” by explicitly focusing on a Nazi massacre of Jews in the famous poem “Babi Yar,” and the Literary Gazette editor who greenlit the poem was sacked.

Some Were More Equal Than Others

Class equality in the Soviet Union was just as phony as anti-racism. In Politics and Pedagogy in the ‘Post-Truth’ Era, Ford admiringly mentions that “wage disparities were relatively minor,” with top officials of the economic ministries earning only three to four times as much as skilled workers. He adds that the earnings gap between the highest- and lowest-paid groups shrank in the 1960s and 1970s.

This comical analysis (“post-truth,” indeed!) leaves out the fact, known to anyone with the remotest familiarity with Soviet life, that living standards in the Soviet Union were not determined primarily by official earnings. Party bosses and high-level government officials received almost everything for free, from palatial apartments and dachas (vacation homes) to chauffeured limousines and consumer goods. There was also a secret hierarchy of “special distribution shops” where even lower-rank members of the party and state bureaucracy could buy groceries—with variety and quality that ordinary citizens could not even dream of, no lines, and lower prices than in regular stores. (My father once got smuggled into such a place by a savvy friend who conned his way past the security guard by insinuating that he knew someone important on the staff, but no purchase could be made without a membership pass.) Shenderovich, the Russian satirist, recalled that at a conference in Irkutsk in the late 1980s, he and his colleagues subsisted on sparse, barely edible meals at a cafe near their hotel—until they learned that they had a pass for the cafeteria of the regional party committee, which offered a cheap five-course dinner featuring such elusive delicacies as tomato salad, venison soup, and baked whitefish.

And then there was the separate shadow economy of blat (favors) based on connections and access. (“It’s not what you know, it’s who you know” was never as true as in the Soviet Union.) For instance, if you could arrange a bed at an elite hospital or admission to a prestigious university—either through your own job or through someone you knew—that could be a ticket to a steady supply of quality food, coveted theater seats, a washing machine, or imported footwear. There was also real money to be made on the black market. If you worked for a store or a warehouse, you pretty much had it made—unless you got greedy and reckless enough to get arrested. People with nothing to steal (engineers, for example) were out of luck.

This fundamental lack of understanding of how the Soviet system of privilege worked is also evident in a hilarious 2018 article in Jacobin, summed up in a tweet that got a well-deserved drubbing: “For all the Soviet Union’s many faults, by traversing its vast architectural landscape, we can get a glimpse of what a built environment for the many, not the few, could look like.” The prime example of architecture “for the many” invoked by author Marianela D’Aprile, an activist with the Democratic Socialists of America, is an elegant writers union resort on Lake Sevan in Armenia that radiated a “quiet luxury.” That is D’Aprile’s “glimpse of [a] possible better world.” Under capitalism, she writes, such a building would be owned by profit seekers and “reserved for those who can pay large sums”—but imagine “if unions could send their members to their lakeside resort.”

One can only wonder whether D’Aprile is genuinely unaware that a writers union resort in the Soviet Union would have been reserved for the cream of the elite, or just willfully blind to facts that might get in the way of her fantasy. To be sure, union-run resorts for ordinary people did exist. In the Soviet Union’s early decades, they provided heavily regimented vacations that stressed physical fitness and were spent with one’s “labor collective,” not with family; later, they became more relaxed and family-oriented. But the accommodations definitely did not exude “quiet luxury”: they generally ranged from atrocious to decent-but-accessible-only-with-connections.

Another major aspect of how privilege operated in the Soviet Union could be summed up in the famous maxim about real estate: location, location, location. My family was immensely privileged simply by virtue of having been born in the capital. A Moscow propiska (the residency permit that each Soviet citizen was required to have) was one of the most coveted things in the country, an incentive to sham marriages, ingenious schemes, and elaborate deceptions. The city enjoyed a special status when it came to snabzheniye (supply of food and consumer goods), quality of services, housing, medicine, and so on. Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) was only a notch below. Other large cities were in the second tier, and it was a downward slope from there until you got to small towns mired in squalor, deprivation, and crime (especially drunken violence). There, you would find decrepit housing, grungy food stores with bare shelves, dismal transit, and worse roads. A bus trip could easily expand from one hour to three in bad weather.

My parents and I saw some of this firsthand in 1979 when, already waiting for an exit visa, we decided to visit Yaroslavl and Rostov, two towns notable for their medieval Russian architecture. The architecture was not in great shape, but everything else was truly grim. There was nothing but stacks of canned fish at one store, boxes of fudge candy at another. Want food? Be prepared to line up outside a couple of hours before opening, a saleswoman explained. The shelves emptied quickly.

On weekends, hordes of people from towns as far as a four- or five-hour ride away from Moscow would scramble aboard trains to go to the capital in search of food, braving not only the long trip but frequent open hostility from Muscovites. Once, when my mother was standing in line at a grocery store, some of her fellow shoppers turned viciously on a shabbily dressed old woman they felt was buying too much—and all the more when she explained it was for her grandson in some godforsaken Soviet Hicksville. An angry chorus erupted, blaming out-of-town interlopers for the food shortages (“You people come here and pick everything clean!”). When my mother tried to intervene, they turned their ire on her, saying she was no doubt an out-of-towner herself or she wouldn’t be sticking up for the old woman.

All Soviet citizens were equal, of course. But there were so many ways in which some were very much more equal than others.

The Patriarchy Strikes Back

The most mystifying of resurgent left-wing myths about the Soviet Union, though, is that of Soviet sexual liberality and gender progressivism. I always wonder if the Twitter tankies with rainbow flags or “queer” and “pansexual” labels in their profiles are aware that sexual relations between men were a criminal offense in the Soviet Union for most of its existence. One could point out that the first criminal code of the Russian Soviet Republic in 1923 did not, in contrast to czarist Russia, criminalize sex between two males. But in a 1995 article in The Journal of Homosexuality, historian Laura Engelstein argues that the 1934 restoration of criminal penalties was not “a clear reversal of the seemingly enlightened legal practice of the 1920s”; in fact, “Soviet courts tried to repress sexual variation even when homosexuality was not a crime,” as early as 1922.

At best, the early Bolshevik revolutionaries regarded homosexuality as a sickness and a perverted manifestation of bourgeois decadence. In later years, all it could take to send a man to prison was a neighbor’s testimony that he often had male overnight visitors but no visible girlfriends. Unlike most American sodomy laws, the Soviet version required no evidence of specific sexual acts. Meanwhile, Soviet culture ruthlessly censored anything gay: Thus, the Soviet edition of the letters and diaries of Peter Tchaikovsky scrubbed numerous passages in which the composer discussed his same-sex attraction as well as encounters and relationships with young men.

Women’s liberation fared only slightly better. True, the early days of the revolution saw an upsurge in female activism, and the Bolsheviks strongly advocated equality of the sexes. In a 1918 speech to a congress of female workers, Lenin declared that the Soviet republic must make it a top priority to ensure equal rights for women. But ultimately, women’s rights were only a means to an end: As Lenin said in the same speech, equality was essential because “the experience of all liberation movements shows that the success of a revolution depends on the extent to which women participate in it.”

The revolution won; women, not so much. While they joined the workforce en masse, aided by universally available (if poor quality) day care, Lenin’s promise of liberation from “petty and mind-numbing” domestic drudgery didn’t quite pan out. The Soviet woman’s “second shift” was made much worse by scarcity, lack of conveniences, and a consumer sector in which the customer was always screwed. Shopping alone was practically a full-time job, between standing in line and going from store to store to find different items; once the shopping was done, you had to factor in some extra time for scraping dirt off the vegetables and throwing out the rotten ones, trying to find the edible parts of what the store laughingly called a steak, or salvaging the milk from a leaky carton. Add to this the fact that the scarcity of decent clothes often made sewing and knitting a necessity rather than a hobby.

Plenty of women could be found in nontraditional jobs, from road repair and other hard physical labor to medicine and engineering (both low-paid and relatively low-prestige), but they were virtually absent from high-level leadership posts. Especially in the post–World War II period, official Soviet culture vigorously reinforced traditional gender norms. Women were celebrated as mothers, men as warriors; in schools, girls had mandatory classes in housekeeping (mainly sewing and cooking) and boys in craft skills. Meanwhile, attempts to start a conversation on feminism in the early 1980s were treated as a subversive bourgeois activity—after all, according to official declarations, the “woman question” in the Soviet Union had been solved by 1930. When a group of women led by Leningrad writer Tatyana Mamonova published an underground feminist almanac in 1980, they were targeted by the KGB; Mamonova and two other contributors were expelled from the Soviet Union, while several others were imprisoned.

Tear Down This Empire

My own personal experience of the Soviet Union was far from the worst of it. My family lived well by Soviet standards. By the time I was growing up, Soviet totalitarianism had gone relatively soft; ideological diktat wasn’t nearly as rigid or omnipresent as some Westerners imagine. Some of the most popular Soviet films and TV movies made in the 1970s were not particularly communist, for example: They were either period pieces (such as a four-part musical miniseries based on The Three Musketeers) or romantic comedies of the “boy meets girl,” not “boy meets tractor,” kind.

And yet it was still a totalitarian system—a system in which I knew at the age of 10 that if I told anyone at school about the things my parents said at home (for instance, that Lenin was not the greatest genius and humanist of all time and that Soviet children were not the happiest in all the world), “Papa will go to jail.” It was a system in which closet dissidents like my parents had to “live by the lie” and regularly demonstrate feigned allegiance to the regime.

It was a system in which “they,” the powers that be, could do anything and the individual could do nothing. When I was in ninth grade, about a year before my family’s departure, word went around my school that everyone graduating at the end of 10th grade would have to spend a year in Siberia “volunteering” on the construction of the Baikal-Amur Mainline railroad. The rumor, generated by the hype in the Soviet press around the project and its enthusiasts in the Young Communist League, turned out to be false. But it was entirely believable, given that college students, some high schoolers, and young adults who already had jobs were routinely dispatched as “volunteers” to collective farms for a month to help with the fall harvest.

It was a system in which any manifestation of personal autonomy or unorthodox interests could make you an enemy of the state. Jazz fans who circulated clandestine copies of Western records were persecuted in the late 1950s. Karate, which became hugely popular in the Soviet Union in the 1970s, was abruptly banned in 1981, reportedly because the authorities were concerned that it was channeling attention away from more important Olympic sports and that it might enable people to fight back against the police in mass protests. Suddenly, teaching karate could earn you a five-year stint in the prison camps.

The Soviet Union’s first few decades were the stuff of nightmares, from the Red Terror, which is believed to have killed over a million people after the Revolution, to the “Terror-Famine” in Ukraine (as well as Kazakhstan and parts of Southern Russia), whose death toll is estimated at 7 million, to Stalin’s Great Terror, in which hundreds of thousands were shot and many more worked to death in the Siberian gulag camps. Among my parents’ friends and coworkers, few did not have a story (if they were candid about it) of a family member or relative imprisoned in the Stalin era for some absurd reason: Someone’s aunt was branded a subversive because a neighbor heard her playing a funeral march on the piano the day a notorious “enemy of the people” was executed; someone’s father was charged with fomenting “defeatist attitudes” during the war for remarking that Stalin “sounded sad” in his radio address to the people.

By the end of its existence, the Soviet Union was an exhausted totalitarian regime trying to maintain its grip on a society that laughed at official pieties, craved consumer goods, was thrilled by the forbidden, and idolized the West. The woman on the bus who had thought it was ridiculous to call the Soviet Union an “evil empire” came to mind, seven or eight years later, when I saw a photo of a rally in Moscow. A sign was being held by someone who, like me, had lived under the reality of communism. It said: “THE USSR: YES, IT IS THE EVIL EMPIRE!”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3GQhB7p

via IFTTT